The Definitives

Goodfellas

Essay by Brian Eggert |

“As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster.”

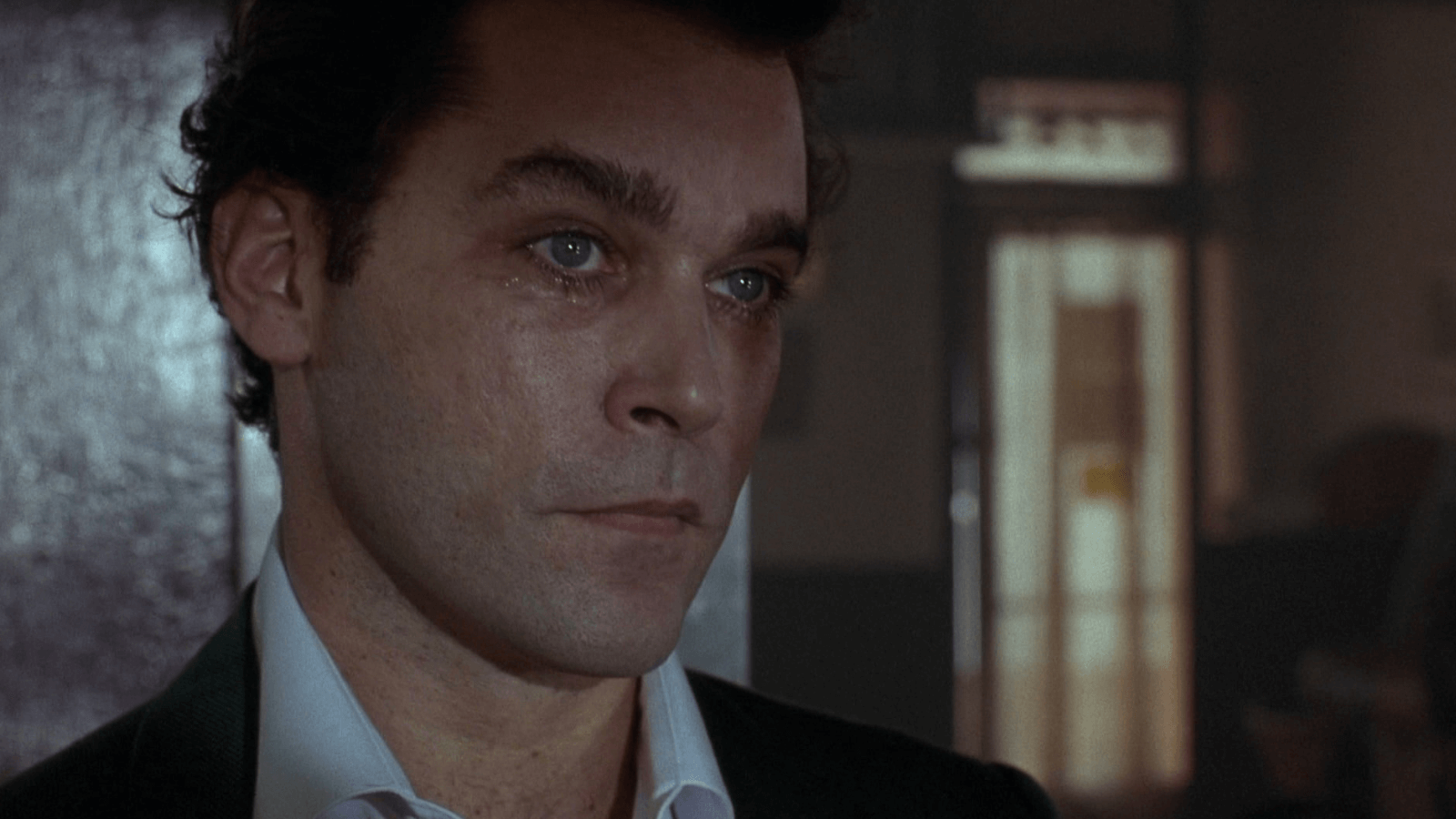

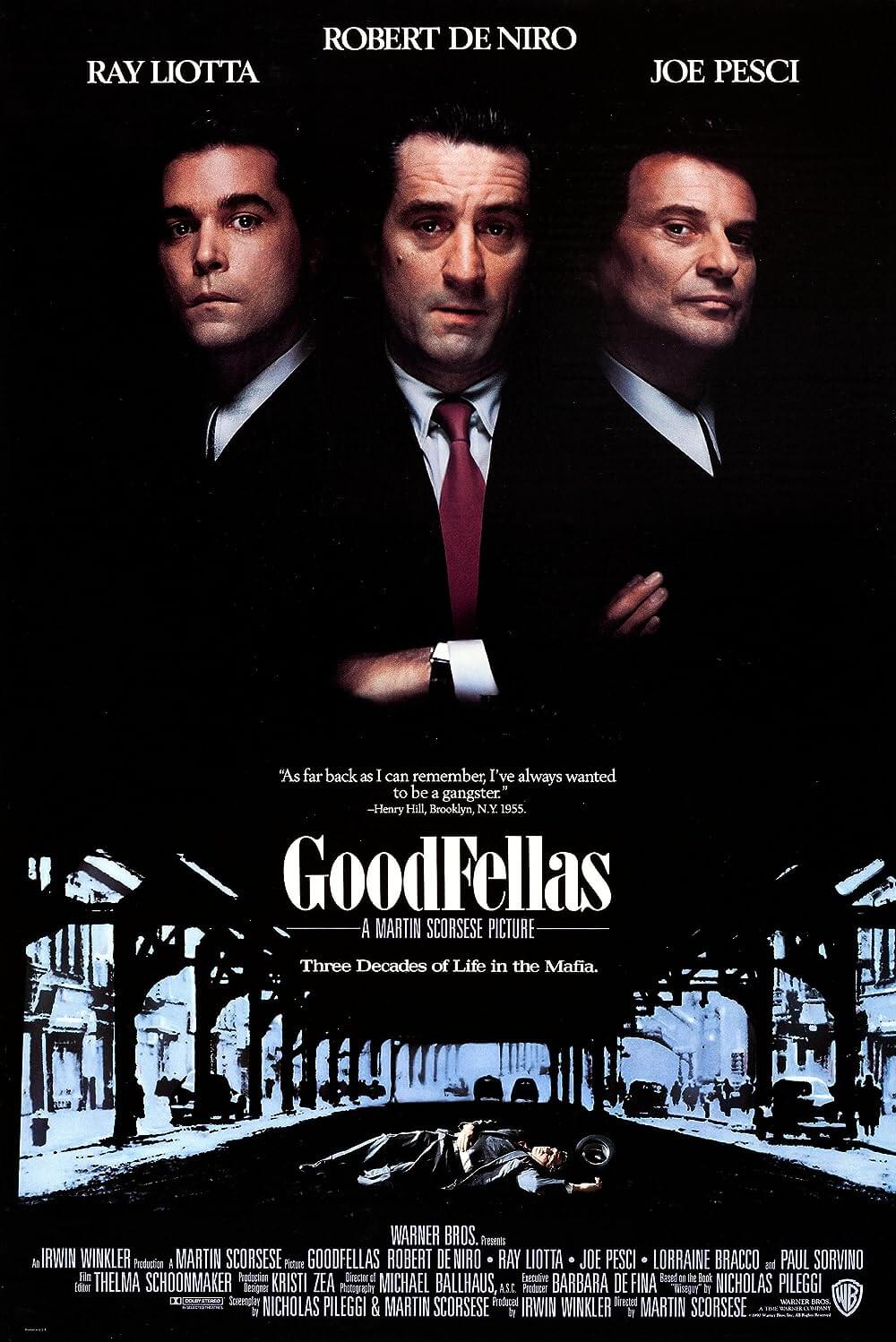

That early line in Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas, spoken by its protagonist, Henry Hill, played to fiery perfection by Ray Liotta, begins the ensuing marathon of compartmentalization. It begs the question: Why does Henry want to be a gangster? When he speaks this first line of his almost omnipresent narration, the situation is precarious. He and two fellow wiseguys, Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci) and Jimmy Conway (Robert De Niro), have pulled off the road to check a noise from the trunk. A made guy, supposedly untouchable, writhes in the back, clinging to life. Tommy delivers a few heated blows with a kitchen knife, and Jimmy finishes the job with four gunshots, putting their victim out of his misery, all of them bathed in hellfire red from the rear lights of the car. Later, they will bury their victim. After six months, they will have to move the decomposing corpse to another location, prompting Henry to vomit violently while his compatriots crack jokes. Given miserable circumstances like these, one should again ask: Why does Henry want to be a gangster? Throughout the film, he remarks on the power and freedoms of the wiseguy lifestyle, and the breakneck filmmaking conveys the associated euphoria. Scorsese portrays Henry’s world through an immersion in his subjectivity, a first-hand testimony rendered with an infectious energy and style. All the while, Henry conveniently ignores or suppresses the grim realities and many contradictions between his métier and how he talks about that world.

Upon its release in 1990, a similar effect spread among viewers like an infection. Many critics questioned whether Scorsese was endorsing or glorifying the mafia’s behaviors. At the same time, superfans hung Goodfellas posters on their walls, looking upon the three floating, imposing leads and admiring their we-take-shit-from-no-one expressions. Just as Henry doesn’t seem able to confront oppositional ideas about his lifestyle—that the criminal organization he romanticizes might not be the bastion of personal freedom and solidarity that he claims—many viewers misread the film’s mordant humor, crackling pace, and criminal milieu as a male fantasy. But Scorsese and fellow screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi, writer of the 1985 nonfiction book Wiseguy: Life in a Mafia Family, which supplied the screen story’s foundation, did not set out to thrill and therein convert their audience to Henry’s criminal lifestyle. They wanted to seduce and then infuriate viewers. Scorsese intended to portray the half-Irish, half-Italian Henry Hill and his beloved Italian mafiosos as corrupt, hypocritical, and alternating between horrific and funny so the viewer would understand what Henry found so attractive about this world. But they also intended to portray gangsterism as a miserable, stressful, and, in the end, thankless existence. With how frequently reactions to Goodfellas go against what the director intended, it’s worth questioning whether Scorsese succeeded in his artistic ambitions.

However, this is a recurring trend in the responses to Scorsese’s work, which regularly steeps audiences into self-contained worlds of toxic masculinity and amoral behavior, and underscores how many moviegoers struggle to engage with and interpret a text. Going back to Mean Streets (1973), following low-level street thugs on a reckless path of self-destruction, Scorsese has consistently implanted spectators in his characters’ subjectivity while never moralizing or offering polemical repudiation of their behavior. In many ways, Mean Streets uses the same narrative and formal techniques as Goodfellas to achieve its effect, including a similar bathing of characters in red light, a familiar blend of levity and toxicity, and a main character who compartmentalizes his criminality. Though, Harvey Keitel’s Charlie at least feels Catholic guilt about his crimes; he seeks to atone physically, holding his finger over a flame to feel “the pain of hell.” Charlie remarks, “The pain in hell has two sides. The kind you can touch with your hand; the kind you can feel in your heart—your soul, the spiritual side. And you know, the worst of the two is the spiritual.” Although Charlie grapples with the morality of his life, Henry shows no such regret in Goodfellas. Take when Henry seems shocked after Tommy impulsively shoots Spider (Michael Imperioli), but he doesn’t object on moral grounds or lose sleep over what happened. Such unquestioning acceptance of this lifestyle has led to a debate about what message Scorsese intends to impart.

Scorsese told Stephen Colbert that he sought to depict “the glamour of evil” with Goodfellas. His artistic goal is to understand the world from within it. What often makes Scorsese’s pictures initially so divisive is also what makes them venerable works of art: they confront, entertain, and require the audience to read them. Scorsese admitted to critic David Ehrenstein, “I want to provoke the audience. Like in Goodfellas. What these people do is morally wrong, but the film doesn’t say that.” Scorsese’s commitment to provocation often comes into question, inciting a brand of aesthetic discourse that goes back to Plato’s arguments in The Republic about art being mere “imitations” that cannot “grasp the truth” and only represent the face value. Of course, aesthetic theorists have countered Plato, placing the role of interpretation on the viewer. More than most filmmakers, Scorsese’s pictures require much from his audience, sometimes to the film’s detriment. For instance, Scorsese’s complete absorption into the mind of Travis Bickle is what made Taxi Driver (1976) compelling, and the film’s message remains a regular topic of debate, along with its portrait of a racist main character and its effect on its audience—just ask John Hinkley Jr., whose obsession with the film and its star Jodie Foster led to an assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan in 1981. More recently, Scorsese’s look at duplicitous, hard-partying brokers in The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) tested the limits of many viewers—read Esther Zuckerman’s article in The Atlantic, “‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ Is a Douchebag’s Handbook”—who could not interpret for themselves that the filmmaker did not sanction the debauchery, hedonism, and duplicity shown in the film.

Scorsese told Stephen Colbert that he sought to depict “the glamour of evil” with Goodfellas. His artistic goal is to understand the world from within it. What often makes Scorsese’s pictures initially so divisive is also what makes them venerable works of art: they confront, entertain, and require the audience to read them. Scorsese admitted to critic David Ehrenstein, “I want to provoke the audience. Like in Goodfellas. What these people do is morally wrong, but the film doesn’t say that.” Scorsese’s commitment to provocation often comes into question, inciting a brand of aesthetic discourse that goes back to Plato’s arguments in The Republic about art being mere “imitations” that cannot “grasp the truth” and only represent the face value. Of course, aesthetic theorists have countered Plato, placing the role of interpretation on the viewer. More than most filmmakers, Scorsese’s pictures require much from his audience, sometimes to the film’s detriment. For instance, Scorsese’s complete absorption into the mind of Travis Bickle is what made Taxi Driver (1976) compelling, and the film’s message remains a regular topic of debate, along with its portrait of a racist main character and its effect on its audience—just ask John Hinkley Jr., whose obsession with the film and its star Jodie Foster led to an assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan in 1981. More recently, Scorsese’s look at duplicitous, hard-partying brokers in The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) tested the limits of many viewers—read Esther Zuckerman’s article in The Atlantic, “‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ Is a Douchebag’s Handbook”—who could not interpret for themselves that the filmmaker did not sanction the debauchery, hedonism, and duplicity shown in the film.

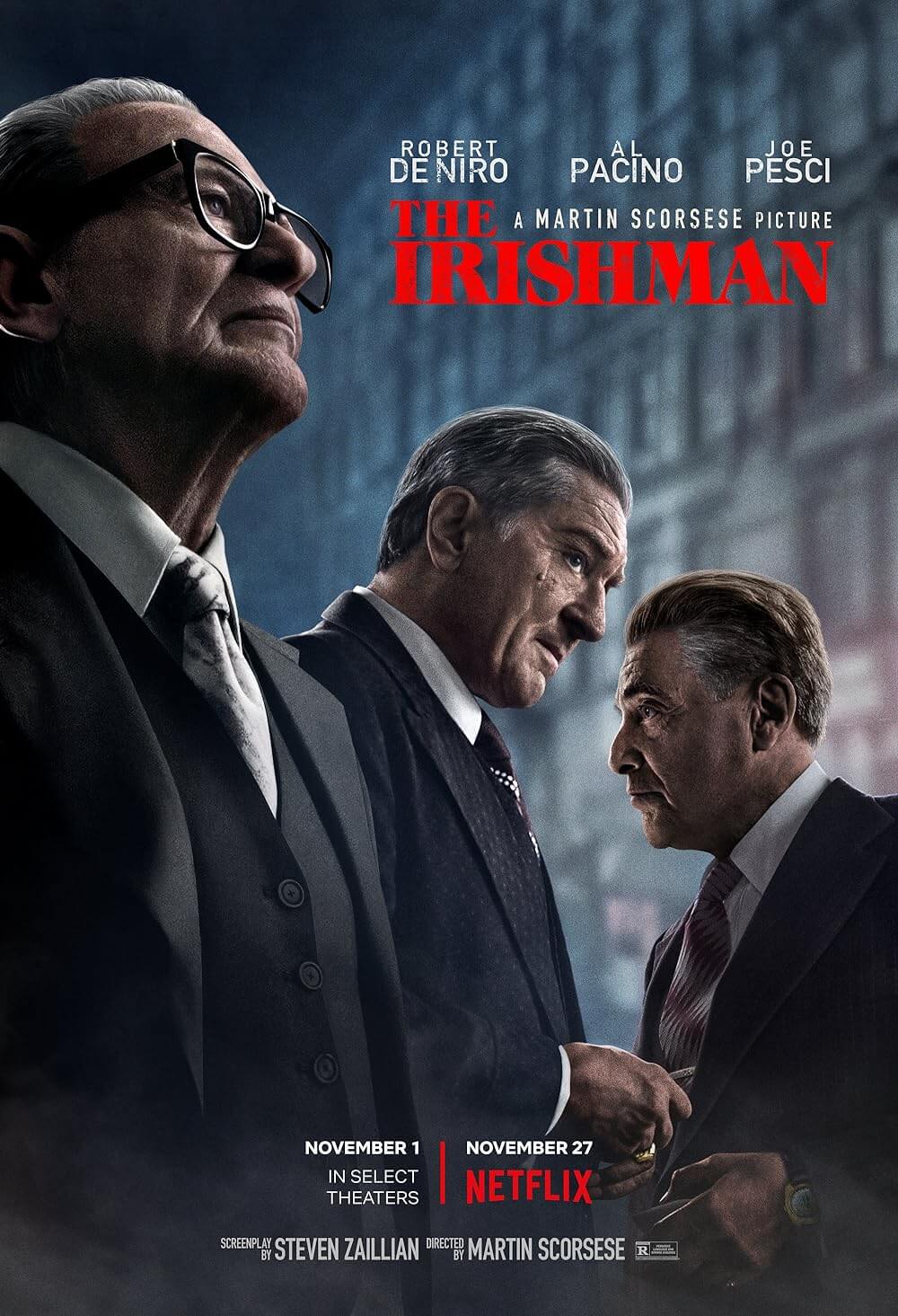

Scorsese resists wagging his finger at his characters or openly decrying their behavior. He respects his audience too much to resort to moralizing and assumes they can interpret his message without him having to spell out its meaning. And while each reviewer or spectator is entitled to their interpretation, some might do better to attempt to understand what Scorsese was going for. Indeed, even as Scorsese tells stories about criminal behavior, his initial interest in these characters stems from how they rationalize their lives. He shows characters such as Henry Hill in deadly organizations, compartmentalizing their sanctimoniousness and criminality in favor of the personal benefits their worlds supply. In Mean Streets, a faith-based exchange occurs, where Keitel’s Charlie hopes his physical self-punishment will be enough to account for his street crimes; however, the thought of leading a moral life to end his internal conflict never occurs to him. The examples throughout Scorsese’s career persist as late as The Irishman (2019) and Killers of the Flower Moon (2023). The former features a passive De Niro as a mob hitman who never questions why he kills because, like in World War II, his need to follow orders and do the prescribed thing negates any sense of his internal morality, which emerges tragically late. In the latter film, compartmentalization allows Leonardo DiCaprio’s dullard to go along with a plot to murder the Osage people for their oil money despite loving his wife, an Osage woman whose family he has preyed upon.

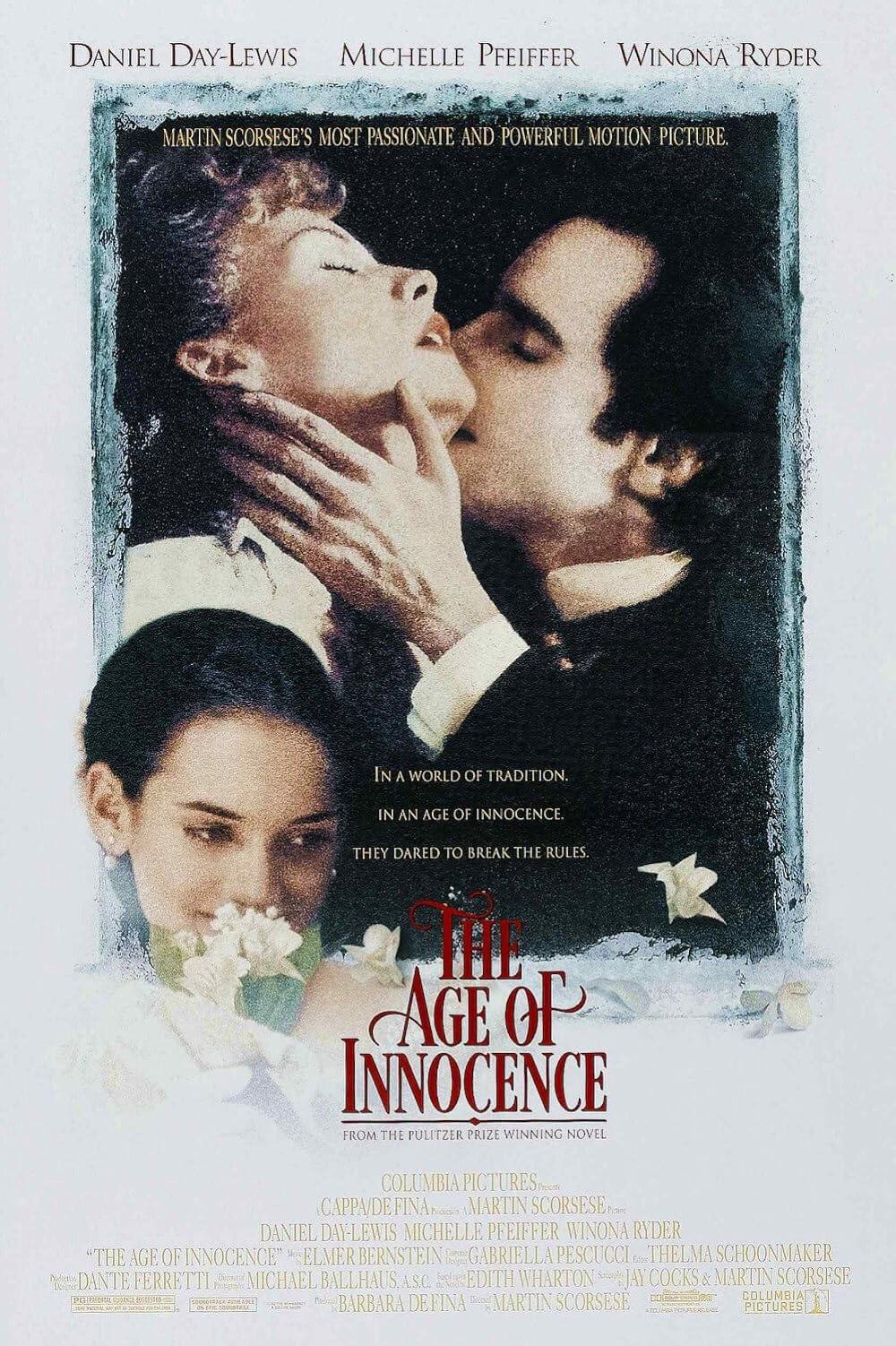

However frequently these themes appear in Scorsese’s filmography, they had not been present in his work for some time before Goodfellas. When discussions about adapting Pileggi’s book began in the mid-1980s, Scorsese’s career floundered in a decade of commercial gambles and creative transition. While spending much of the 1980s attempting to get The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) made, he explored other genres. He took director-for-hire jobs that allowed him the freedom to experiment, resulting in some of his most inventive work on The King of Comedy (1982) and After Hours (1985), while elsewhere, he earned commercial success on The Color of Money (1986). Still, he was uniquely suited to the subject matter of Wiseguy, having witnessed the gangster lifestyle in his youth. His Italian-American upbringing in New York’s Little Italy neighborhood featured gangsters as part of the natural environment; even his best friend during childhood was a mobster’s son. Better than any other filmmaker, Scorsese could understand how someone could be drawn into the gangster lifestyle, extolling its perks while subjecting themselves to its dangers. Still, after Mean Streets and Raging Bull (1980), Scorsese had wanted to move on from mobsters, yet he couldn’t help but appreciate Pileggi’s honest and romance-free depiction of that world.

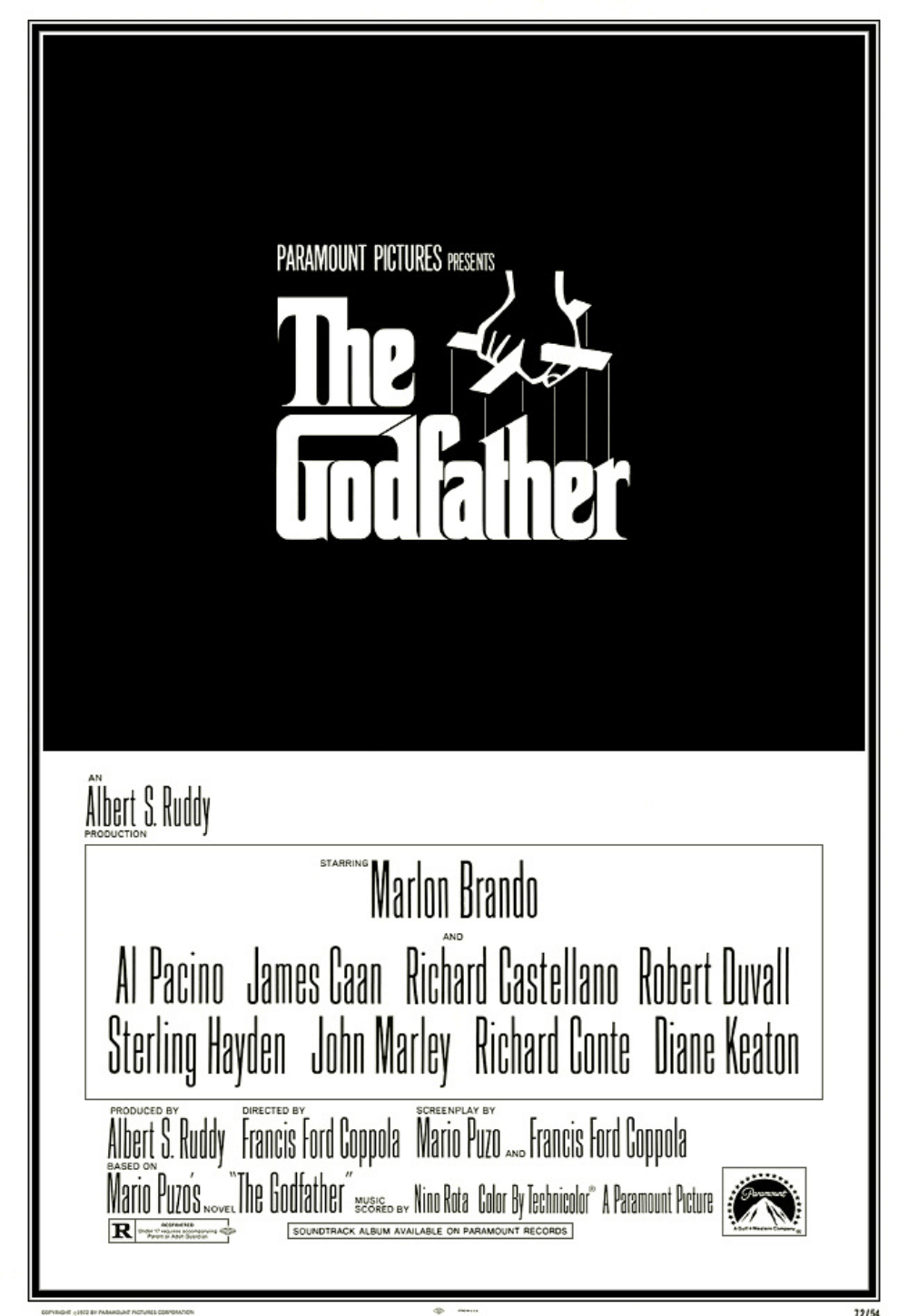

Pileggi started out as a journalist covering crime for the Associated Press in 1956 and became New York magazine’s resident “crime expert” in 1968. A native of Brooklyn’s Bensonhurst neighborhood, Pileggi grew up around Italian-American gangsters and earned a reputation among them as a respectable neighborhood guy, so he knew that world well. His book Wiseguy would mark the first time a mobster told all without coercion or government pressure. The real Henry Hill defied his contacts at the FBI and the US Marshals overseeing his placement in the Witness Security Program (WITSEC) by giving Pileggi his number through an attorney. But Scorsese wouldn’t be the first filmmaker to tackle Hill’s story, despite reading the book in 1986 and immediately wanting to buy the rights to adapt it. Around that time, Pileggi had been dating Nora Ephron, and they would eventually marry in 1987. Ephron’s fascination with mobsters extends from her screenplay for Susan Seidelman’s mob-comedy Cookie (1989) to her many references to The Godfather (1972) throughout her romantic comedy You’ve Got Mail (1998). Ephron also wrote the mob comedy My Blue Heaven (1990), which opened a month before Goodfellas and follows a Henry Hill-like gangster, Vinnie Antonelli, played by Steve Martin, whose time as a schnook in witness protection finds him pining for arugula and building a baseball park in his new San Diego suburb home.

Pileggi started out as a journalist covering crime for the Associated Press in 1956 and became New York magazine’s resident “crime expert” in 1968. A native of Brooklyn’s Bensonhurst neighborhood, Pileggi grew up around Italian-American gangsters and earned a reputation among them as a respectable neighborhood guy, so he knew that world well. His book Wiseguy would mark the first time a mobster told all without coercion or government pressure. The real Henry Hill defied his contacts at the FBI and the US Marshals overseeing his placement in the Witness Security Program (WITSEC) by giving Pileggi his number through an attorney. But Scorsese wouldn’t be the first filmmaker to tackle Hill’s story, despite reading the book in 1986 and immediately wanting to buy the rights to adapt it. Around that time, Pileggi had been dating Nora Ephron, and they would eventually marry in 1987. Ephron’s fascination with mobsters extends from her screenplay for Susan Seidelman’s mob-comedy Cookie (1989) to her many references to The Godfather (1972) throughout her romantic comedy You’ve Got Mail (1998). Ephron also wrote the mob comedy My Blue Heaven (1990), which opened a month before Goodfellas and follows a Henry Hill-like gangster, Vinnie Antonelli, played by Steve Martin, whose time as a schnook in witness protection finds him pining for arugula and building a baseball park in his new San Diego suburb home.

After securing the screen rights to Wiseguy, Scorsese would finish making The Last Temptation of Christ before getting to what eventually became Goodfellas. The title required a change due to a mob-based television show called Wiseguy, which debuted in 1987 and lasted until 1990. The film’s production landed at Warner Bros., an appropriate home given the studio’s reputation for gangster movies during the Golden Age of Hollywood. Classics such as The Public Enemy (1931), Little Caesar (1931), Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), and The Roaring Twenties (1939) adopted a ripped-from-the-headlines approach to Prohibition-era gangsterism. Scorsese would deploy a similar style to Goodfellas, drawing from TV tabloid journalism and documentary aesthetics to consider the anthropology of low-level soldiers in the Italian-American mob. The production’s striking verisimilitude became one of its most enduring hallmarks, accented by the involvement of Hill and many other actual gangsters. Casting director Ellen Lewis even found roles for several real-life mobsters, adding to the film’s warm reception in their circles. In GQ’s oral history to celebrate the film’s twentieth anniversary, Pileggi remarks, “Mob guys love it, because it’s the real thing, and they knew the people in it. They say, ‘It’s like a home movie.’” However, it’s far from a “quasi-documentary,” as scholar Fulvio Orsitto claims.

Goodfellas tells the story of Henry Hill, starting with his modest Brooklyn childhood in the 1950s and his admiration for the freedom and power of the Cicero family gangsters in his neighborhood, headed by Paulie (Paul Sorvino). After landing a job with them as a gopher, he enters their ranks as a teenage petty criminal. Getting accepted into their fold means Henry will be “somebody in a neighborhood full of nobodies,” he observes in his narration, which sounds like witness testimony upon reflection of the film’s courtroom finish. Indeed, Henry recalls his role in the organization over the next two-and-a-half decades, from joining Jimmy and Tommy on heists and shakedowns to starting up a cocaine side hustle. Meanwhile, he marries a Jewish woman from the neighborhood, Karen (Lorraine Bracco), and has two kids, which never prevent him from carrying on with a girlfriend, Janice (Gina Mastrogiacomo), or his eventual drug cutter Sandy (Debi Mazar). Although Henry will never be a full member of the Italian crew due to his Irish blood, Tommy can still be “made.” It’s a big moment for Henry and Jimmy when that’s set to happen. But the bosses whack Tommy instead—payback for the unauthorized killing of a made man, Billy Batts (Frank Vincent), the guy from the trunk. Despite robberies and assault on his list of crimes, cocaine, which Paulie warns him not to mess with, eventually brings Henry down. His capture prompts him to turn over his so-called family members and disappear into WITSEC to some anonymous suburban purgatory.

The events in Goodfellas are less important than the flavor of realism and personal reflection with which Scorsese presents them. Certainly, its iconic scenes have been fixed into the lexicon of great movie moments, inspiring countless homages. Even people who have never seen the film know the “How am I funny?” scene, spoofed most memorably in the “Goodfeathers” segments on TV’s Animaniacs (1993-1998), featuring a Pesci-esque pigeon with a temper. However, the events in Henry’s life prove secondary to the general portraiture of his world. Consider how much time Henry spends talking about the planning and aftermath of the famous Lufthansa heist, which has been the subject of several books and other movies. Yet, Henry was not there. And in keeping with the film’s structure as a cinematic rendering of Henry’s, and to a lesser degree Karen’s, recollections, Scorsese does not show what occurred at the airline. The film serves as a statement of the facts as Henry and Karen see them, given either as witness testimony, personal accounts to Pileggi, or true confessions to the viewer. In keeping with the nonfiction source material, Scorsese is committed to realism in Goodfellas. Production designer Kristi Zea oversaw the obsessive attention to every detail insisted on by Scorsese, Pileggi, and the actors: the Italian fabrics imported for the costumes; the faux commercial for Morrie’s (Chuck Low) toupée business, modeled after the real thing; the vintage watches in the actor’s pockets, which never see screen time; the real rolled-up wad of cash De Niro kept on him during the shoot.

The events in Goodfellas are less important than the flavor of realism and personal reflection with which Scorsese presents them. Certainly, its iconic scenes have been fixed into the lexicon of great movie moments, inspiring countless homages. Even people who have never seen the film know the “How am I funny?” scene, spoofed most memorably in the “Goodfeathers” segments on TV’s Animaniacs (1993-1998), featuring a Pesci-esque pigeon with a temper. However, the events in Henry’s life prove secondary to the general portraiture of his world. Consider how much time Henry spends talking about the planning and aftermath of the famous Lufthansa heist, which has been the subject of several books and other movies. Yet, Henry was not there. And in keeping with the film’s structure as a cinematic rendering of Henry’s, and to a lesser degree Karen’s, recollections, Scorsese does not show what occurred at the airline. The film serves as a statement of the facts as Henry and Karen see them, given either as witness testimony, personal accounts to Pileggi, or true confessions to the viewer. In keeping with the nonfiction source material, Scorsese is committed to realism in Goodfellas. Production designer Kristi Zea oversaw the obsessive attention to every detail insisted on by Scorsese, Pileggi, and the actors: the Italian fabrics imported for the costumes; the faux commercial for Morrie’s (Chuck Low) toupée business, modeled after the real thing; the vintage watches in the actor’s pockets, which never see screen time; the real rolled-up wad of cash De Niro kept on him during the shoot.

And yet, the production’s attention to journalistic detail throughout Goodfellas serves Scorsese’s ambition to deconstruct gangster cinema, using what scholar Larissa M. Ennis identifies as “irony, direct-address, and wry juxtapositions between the voice-over narration and the visual content of the film to recast the genre in a new light.” Scorsese’s style gives way to a critical distance that reminds the viewer they’re watching a movie while simultaneously immersing the viewer in Henry’s world—this is the real magic trick of Goodfellas. Like Scorsese’s earlier work, especially Mean Streets, the director employs visual and aural techniques derived from French New Wave directors such as François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard. When Scorsese and Pileggi first started to prepare their script, the director showed him Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1962) to demonstrate what he wanted regarding voice-over and still images. “What I loved about these Truffaut and Godard techniques from the early ’60s was that the narrative was not that important,” Scorsese remarked. The narrative flow could stop for a freeze-frame or an aside, interrupting the story proper for a tangential point. Tabloid television programs such as Hard Copy and A Current Affair use comparable devices, which, by association, add to the film’s exposé quality. Similarly, the voice-over might come from multiple sources, such as when Karen remarks about Henry’s rude behavior on their first date or meeting too many Pauls, Peters, and Maries at their wedding reception. Along with a fourth-wall-breaking finale, the film’s variety of techniques creates an almost Brechtian effect that underscores the cinematic medium.

Scorsese’s use of New Wave methods enlivens Henry’s account of his gangster lifestyle, but it also underlines incongruities between what Henry tells us and what the film shows us. Note how Henry lumps everyone else into the category of suckers: “To us, those goody-good people who worked shitty jobs for bum paychecks and took the subway to work every day, and worried about their bills, were dead.” By contrast, “Anything I wanted was a phone call away.” But Henry and the other gangsters live in tacky houses, their wives wear cheap clothes and bad makeup according to Karen, and they put their lives at risk to maintain this unimpressive facade and acquire the “little extras” for their families. “Our husbands weren’t brain surgeons,” Karen admits. “They were blue-collar guys. The only way they could make extra money, real extra money, was to go out and cut a few corners.” But anyone living too extravagantly risks calling unwanted attention to themselves, and if the authorities don’t get them first, someone else from the crew will whack them for conspicuous spending. Several members of Jimmy’s crew meet this fate after the Lufthansa heist when he attempts to shield himself from suspicion by eliminating anyone else involved. Yet, being part of a crew is supposed to mean that “nobody can fuck around with you,” according to Henry. “It also means you could fuck around with anybody just as long as they aren’t also a member.” This is proven false as well—case in point: Billy Batts.

Meanwhile, Henry faces discrimination in his Italian-American gangster family’s social order. His highest possible role as a mob soldier is determined by his half-Irish ethnicity, which plays a central role in the Cicero family power structure, where only pure-blooded Sicilians can become made men. This fact emphasizes how Henry will forever be a pilot fish in the mob, swimming behind the bigger sharks, picking up scraps. Jimmy and Tommy, the latter being full Italian, have more cred within the family than Henry does—though Jimmy, too, is part Irish. Henry’s status as a relative outsider, however, allows him to observe from a distance and report, which makes his film-long testimony so authentic (and the real Henry such a good subject, according to Pileggi). But ethnicity also reveals another dimension to the deplorable behavior in Goodfellas, whose characters have all manner of nasty things to say about anyone who’s not a straight male of Italian blood, especially people of color. This is nothing new in Scorsese’s cinema. Mean Streets features Keitel’s character pining after a Black dancer he’s socially forbidden to desire. De Niro’s Travis Bickle targets Black people with violence in Taxi Driver, and his Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull transfers his many frustrations on his Black nemesis Sugar Ray Robinson. The wiseguys in Goodfellas reinforce their group identity by treating Blackness as sub-human, with Tommy questioning his girlfriend when she praises Sammy Davis, Jr., saying, “I could see how a white girl could fall for him.” Tommy responds in his typical manner by making a scene, asking, “So you condone that stuff?” The examples of such behavior have inspired analyses of race in the film, but suffice it to say, it’s another aspect of Henry’s world that remains appalling, yet he accepts it.

Meanwhile, Henry faces discrimination in his Italian-American gangster family’s social order. His highest possible role as a mob soldier is determined by his half-Irish ethnicity, which plays a central role in the Cicero family power structure, where only pure-blooded Sicilians can become made men. This fact emphasizes how Henry will forever be a pilot fish in the mob, swimming behind the bigger sharks, picking up scraps. Jimmy and Tommy, the latter being full Italian, have more cred within the family than Henry does—though Jimmy, too, is part Irish. Henry’s status as a relative outsider, however, allows him to observe from a distance and report, which makes his film-long testimony so authentic (and the real Henry such a good subject, according to Pileggi). But ethnicity also reveals another dimension to the deplorable behavior in Goodfellas, whose characters have all manner of nasty things to say about anyone who’s not a straight male of Italian blood, especially people of color. This is nothing new in Scorsese’s cinema. Mean Streets features Keitel’s character pining after a Black dancer he’s socially forbidden to desire. De Niro’s Travis Bickle targets Black people with violence in Taxi Driver, and his Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull transfers his many frustrations on his Black nemesis Sugar Ray Robinson. The wiseguys in Goodfellas reinforce their group identity by treating Blackness as sub-human, with Tommy questioning his girlfriend when she praises Sammy Davis, Jr., saying, “I could see how a white girl could fall for him.” Tommy responds in his typical manner by making a scene, asking, “So you condone that stuff?” The examples of such behavior have inspired analyses of race in the film, but suffice it to say, it’s another aspect of Henry’s world that remains appalling, yet he accepts it.

Being a gangster isn’t “a license to do anything,” despite Henry’s claim. Instead, it’s better described as an alternative lifestyle, operating in ways that create the illusion of control. When The System fails, gangsterism provides “protection for people who can’t go to the cops,” Henry argues. It supplies a feeling of defiance against traditional lifestyles for people who might not cut it in the real world, and so they undercut, steal, intimidate, and murder to get their way, creating a world on their terms. Henry proudly affirms, “I was part of something. I belonged.” And while Henry remains uncritical of this world and its morality, Karen is more aware of her conflicted feelings about her husband’s gangster lifestyle, showing more evidence of cognitive dissonance than her husband: “I know there are women, like my best friends, who would have gotten out of there the minute their boyfriend gave them a gun to hide. But I didn’t. I got to admit the truth. It turned me on.” Even so, there are rules to this world as in the conventional, law-abiding world, and the punishments prove even more severe. Get out of line, and you might get whacked. Are the risks worth the rewards? For Henry, it seems so. Still, in his book about the film, Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas, critic Glenn Kenny observes, “It never occurs to Henry that he may have traded a leash for a noose.” But there was never a trade for Henry; he entered this life as a kid, his parents supplying Henry’s only exposure to a normal lifestyle. Henry has never worked a straight day in his life, so there’s hardly a comparison or moral framework for Henry to judge his life against. When he’s eventually caught and giving testimony from the courtroom in the final scene, he does not regret his actions; he can only mourn the loss of his freedoms: “I’m an average nobody. I get to live the rest of my life like a schnook.”

Even though Henry’s world contains contradictions, prejudice, and danger that arguably negates its freedom, Scorsese’s whirlwind aesthetic captures its addictive high, where “distortion, hyperbole, and exuberance all commingle,” as Pauline Kael notes in her New Yorker review. Kale argued the film is a male fantasy, claiming it’s about “being a guy and guys getting high on being a guy.” To be sure, the visual bravado Scorsese brings to this picture captivated many viewers while conveying Henry’s enthusiasm for the mob life, from the famous one-shot Steadicam sequence through The Copacabana to the many rompish episodes where crime pays. The sheer virtuosity with which every scene arrives and folds into the next makes the 149-minute runtime feel about half that. It’s a testament to Scorsese’s longtime collaboration with editor Thelma Schoonmaker, whose rhythms, pauses, and interruptions move in harmony with the nimble brio of Michael Ballhaus’ superb cinematography. And then Scorsese, serving as his own music supervisor, layers each scene with music that adds another energetic dimension. The director had worked out what songs he wanted in the film during the scripting phase, noting soundtrack choices in the initial screenplay—from Cream’s guitar riff on “Sunshine of Your Love” to accent Jimmy’s deadly presence, to Donovan’s “Atlantis” to underscore the mythical sinking of Henry, Tommy, and Jimmy as they attack Batts for insulting Tommy and telling him, “Now go home and get your fuckin’ shinebox.”

Getting swept up in this perfect visual and aural storm is effortless, even though its collapse—a frenzied 10-minute sequence set on May 11, 1980, involving a gun deal, a cocaine drop, some delicious-looking meat sauce, and justified paranoia about a helicopter—looks nightmarish. Scorsese captures the essence of how being a gangster makes you feel alive, and, in Henry’s case, cocaine heightens that even further. Henry’s excitement throughout the film is laden with humor and crackles with the electricity of improvisations by the actors, especially Pesci, who manages to conjure laughter out of the most unlikely situations. The film’s gallows humor can be infectious, though it’s often contained within disturbing scenes, such as the amusing late-night dinner with Tommy’s mother (Catherine Scorsese, the director’s mother)—a delightful presence intent on feeding her hungry guys and showing off her painting—while Batts barely clings to the life in the car trunk just outside. Goodfellas constantly puts the viewer into situations that, on the surface, should be horrific, yet they prove entertaining and funny. They play on the razor’s edge between exhilarating and scary, with the “How am I funny?” scene serving as a synecdoche for the film’s effect—dangerous and elated. Which is to say, that’s how Henry sees his wiseguy lifestyle. It’s a constant influx of heightened stimulation from violence, power, sex, and drugs, and accented by Scorsese with rock ‘n’ roll.

Getting swept up in this perfect visual and aural storm is effortless, even though its collapse—a frenzied 10-minute sequence set on May 11, 1980, involving a gun deal, a cocaine drop, some delicious-looking meat sauce, and justified paranoia about a helicopter—looks nightmarish. Scorsese captures the essence of how being a gangster makes you feel alive, and, in Henry’s case, cocaine heightens that even further. Henry’s excitement throughout the film is laden with humor and crackles with the electricity of improvisations by the actors, especially Pesci, who manages to conjure laughter out of the most unlikely situations. The film’s gallows humor can be infectious, though it’s often contained within disturbing scenes, such as the amusing late-night dinner with Tommy’s mother (Catherine Scorsese, the director’s mother)—a delightful presence intent on feeding her hungry guys and showing off her painting—while Batts barely clings to the life in the car trunk just outside. Goodfellas constantly puts the viewer into situations that, on the surface, should be horrific, yet they prove entertaining and funny. They play on the razor’s edge between exhilarating and scary, with the “How am I funny?” scene serving as a synecdoche for the film’s effect—dangerous and elated. Which is to say, that’s how Henry sees his wiseguy lifestyle. It’s a constant influx of heightened stimulation from violence, power, sex, and drugs, and accented by Scorsese with rock ‘n’ roll.

When Goodfellas debuted in 1990, it arrived nearly two decades after Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather, which inspired a strain of imitators and similarly staged epics, including Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America (1984) and David Mamet’s Things Change (1988). They treat the Italian mob as operatic and sometimes romanticize their behaviors with music from the old country and a general regality—the same brand of self-satisfaction that permeates Frank Sinatra music. By contrast, Scorsese’s film questions everything with its grimy realism and none of the myth-making found in Coppola’s film (which, many forget, presents a damning critique of American capitalism). Since Scorsese’s film is not a grand dramaturgy but a personal testimony, he punctuates Goodfellas with a startling shot of Tommy, dressed in an outfit he wore earlier when robbing a truck, facing the camera and shooting a pistol at the audience—an homage to the 1904 Western short The Great Train Robbery, in which an outlaw does the same. The final shot shows Henry returning to his WITSEC home after getting the paper, dressed in an unflattering light blue robe. On the soundtrack, the Sex Pistols’ cover of Sinatra’s “My Way” blares in self-destructive rebellion, echoing the volatility of the band’s frontman, Sid Vicious, who died at 21 after a brief but frenzied life of drugs, violence, and attitude. Henry is just as unapologetic about his choices. The lyrics—“Regrets I’ve had a few/But then again, too few to mention/I did what I had to do/I saw it through without exemption”—couldn’t be more appropriate, nor could the song choice as a parallel to Goodfellas’ punkish status in the gangster genre at that time.

Today, the film’s legacy cannot be overstated. It’s regularly hailed as the director’s best work, and many publications and list-makers have ranked it the greatest mob movie ever made. Scorsese has returned to the organized crime well a few times since, with 1995’s Casino sharing the most in common with Goodfellas. Scorsese reteamed with Pileggi to tell the story planned for the author’s book, Casino: Love and Honor in Las Vegas. The two once again collaborated on the script, which was completed before the book’s publication, while De Niro, Pesci, and others from Goodfellas signed on to star. Many of them would return for The Irishman. But the film’s reach extends to prestige television as well. David Chase, creator of HBO’s The Sopranos, often considered the best television series ever made, admits he couldn’t have conceived his show without Goodfellas. During its run (1999-2007), The Sopranos became the benchmark for scripted television series in the twenty-first century, launching a slew of imitators, each about a complex white man who oversees a criminal organization, which is both appealing and morally corrupt. By extension, without Goodfellas, television shows such as Deadwood, Breaking Bad, Better Call Saul, Ozark, Boardwalk Empire, Peaky Blinders, Lilyhammer, Sons of Anarchy, Brotherhood, Gomorrah, and many others would probably not exist.

More than any of its consequents, Goodfellas captures the pulse of gangster life, not just to understand what motivates these people and how they compartmentalize their choices, but to supply the audience with a shock treatment of aversion. In a persistent mode of seduction and repulsion, Scorsese balances Henry’s testimony with the reality of his downfall. Henry may romanticize gangsterism, but the film does not. And while Scorsese uses a dichotomy of visual techniques, from splashing his characters in hellish reds or employing French New Wave devices, the film is not an expressive tragedy in the Greek tradition. Henry’s downfall isn’t so much tragic as it is earned. In her pan, Kael rightly observed that Goodfellas “has no arc, and doesn’t climax; it just comes to a stop.” True enough, but that’s not a flaw; it’s an intentional strategy to confront the viewer. Henry had a slice of what he considers the good life—he did things his way—and he lost it, having acted with impunity from the law and having betrayed the rules of his wiseguy family. Scorsese tells a familiar gangster story, going back to the crime-doesn’t-pay lessons characters played by James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson learned in 1930s gangster pictures. But Scorsese revives the genre with vibrant stylization and an entrenched perspective that seduces and, in doing so, entraps the audience as a provocateur might. Whether segments of the audience fall into the lure of Henry’s world or, as intended, recoil from it, Goodfellas continues to exert its influence on anyone who encounters it.

More than any of its consequents, Goodfellas captures the pulse of gangster life, not just to understand what motivates these people and how they compartmentalize their choices, but to supply the audience with a shock treatment of aversion. In a persistent mode of seduction and repulsion, Scorsese balances Henry’s testimony with the reality of his downfall. Henry may romanticize gangsterism, but the film does not. And while Scorsese uses a dichotomy of visual techniques, from splashing his characters in hellish reds or employing French New Wave devices, the film is not an expressive tragedy in the Greek tradition. Henry’s downfall isn’t so much tragic as it is earned. In her pan, Kael rightly observed that Goodfellas “has no arc, and doesn’t climax; it just comes to a stop.” True enough, but that’s not a flaw; it’s an intentional strategy to confront the viewer. Henry had a slice of what he considers the good life—he did things his way—and he lost it, having acted with impunity from the law and having betrayed the rules of his wiseguy family. Scorsese tells a familiar gangster story, going back to the crime-doesn’t-pay lessons characters played by James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson learned in 1930s gangster pictures. But Scorsese revives the genre with vibrant stylization and an entrenched perspective that seduces and, in doing so, entraps the audience as a provocateur might. Whether segments of the audience fall into the lure of Henry’s world or, as intended, recoil from it, Goodfellas continues to exert its influence on anyone who encounters it.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on January 24, 2024. Thank you so much for your generous, continued support, Martha!)

Bibliography:

Baker, Aaron (editor). A Companion to Martin Scorsese, Revised. First Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2021.

Celebretainment. “Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas was hated for showing ‘the glamour of evil.’” HomeNewsHere.com, 30 October 2023. https://homenewshere.com/national/entertainment/article_9d82225a-bde6-5ca9-bafc-ed868f442549.html. Accessed 3 January 2024.

Christie, Ian; Thompson, David (edited by). Scorsese on Scorsese. Revised Edition. Faber, 2003.

Ehrenstein, David. The Scorsese Picture: The Art and Life of Martin Scorsese. Birch Lane Press, 1992.

Ennis, Larissa M. “Off-White Masculinity in Martin Scorsese’s Gangster Films.” A Companion to Martin Scorsese, Revised. First Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2021, pp.173-194.

Kael, Pauline, “Tumescence as Style: Martin Scorsese’s ‘GoodFellas.’” The New Yorker, 17 September 1990. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1990/09/24/tumescence-as-style. Accessed 3 January 2024.

Katz, Wallace. “Sticking Together, Falling Apart: ‘The Sopranos’ and the American Moral Order.” New Labor Forum, no. 9, 2001, pp. 91–99. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40342317. Accessed 23 December 2023.

Kenny, Glenn. Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas. Hanover Square Press, 2020.

“Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas: A Complete Oral History.” GQ.com. 20 September 2010. https://www.gq.com/story/goodfellas-making-of-behind-the-scenes-interview-scorsese-deniro. Accessed 6 January 2024.

McAteer, John. “The Problem of Violence in Scorsese’s Films: The Catholic Gangster as Tragic Hero.” Scorsese and Religion, edited by Christopher B. Barnett and Clark J. Elliston, Brill, 2019, pp. 72–90. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctv2gjwtx2.10. Accessed 23 December 2023.

Murphy, Kathleen. “Made: MEN.” Film Comment, vol. 34, no. 3, 1998, pp. 64–67. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43456487. Accessed 23 December 2023.

Orsitto, Fulvio. “Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas: Hybrid Storytelling Between Realism and Formalism.” Mafia Movies: A Reader, edited by Dana Renga. University of Toronto Press, 2001.

Plato. “The Republic. Book X.” Aesthetics: A Comprehensive Anthology, edited by Steven M. Cahn and Aaron Meskin, Blackwell Publishing, 2008.

Viano, Maurizio. “Review: Goodfellas.” Film Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 3, 1991, pp. 43–50. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1212795. Accessed 23 December 2023.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review