The Definitives

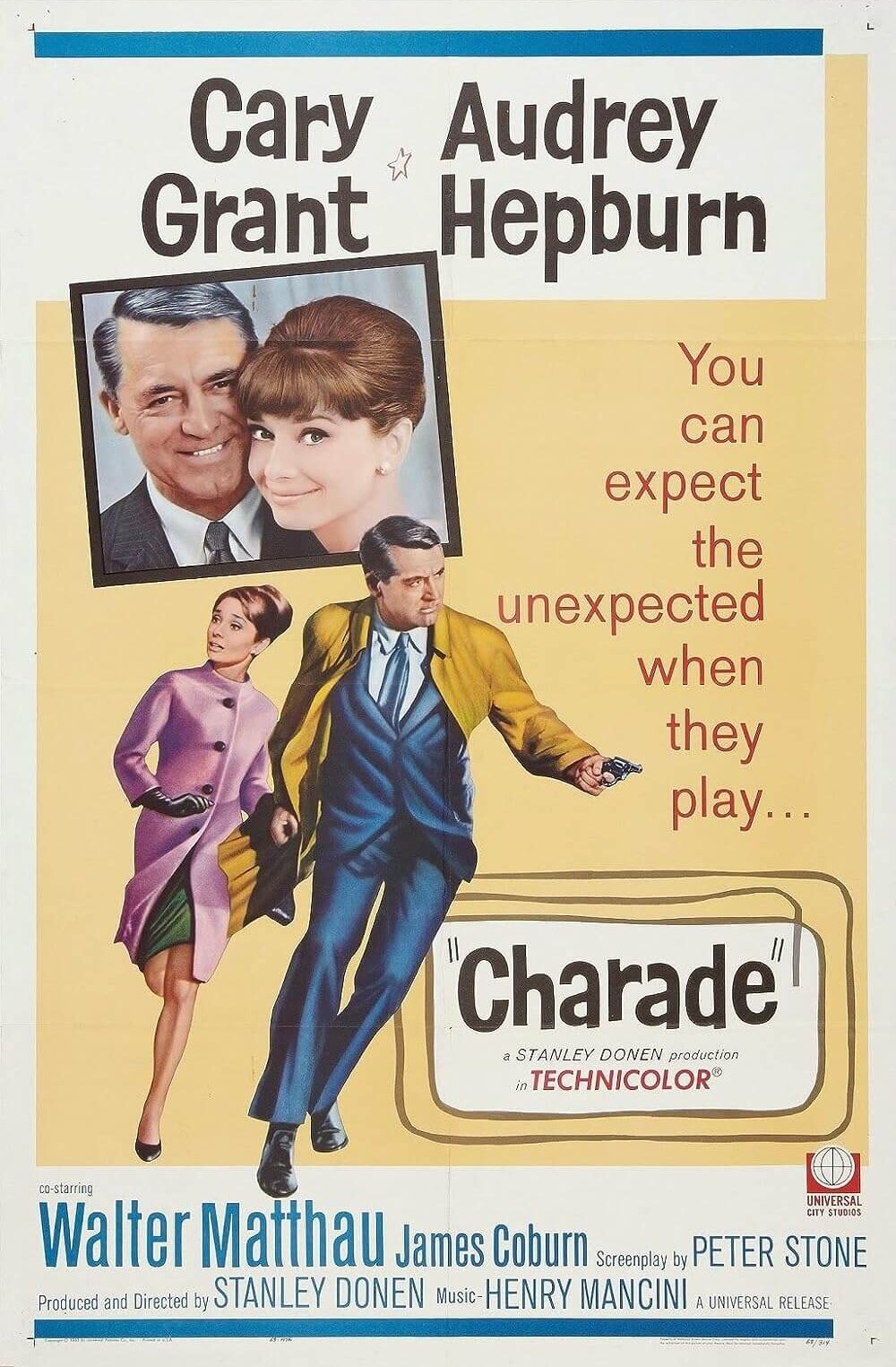

Charade (1963)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

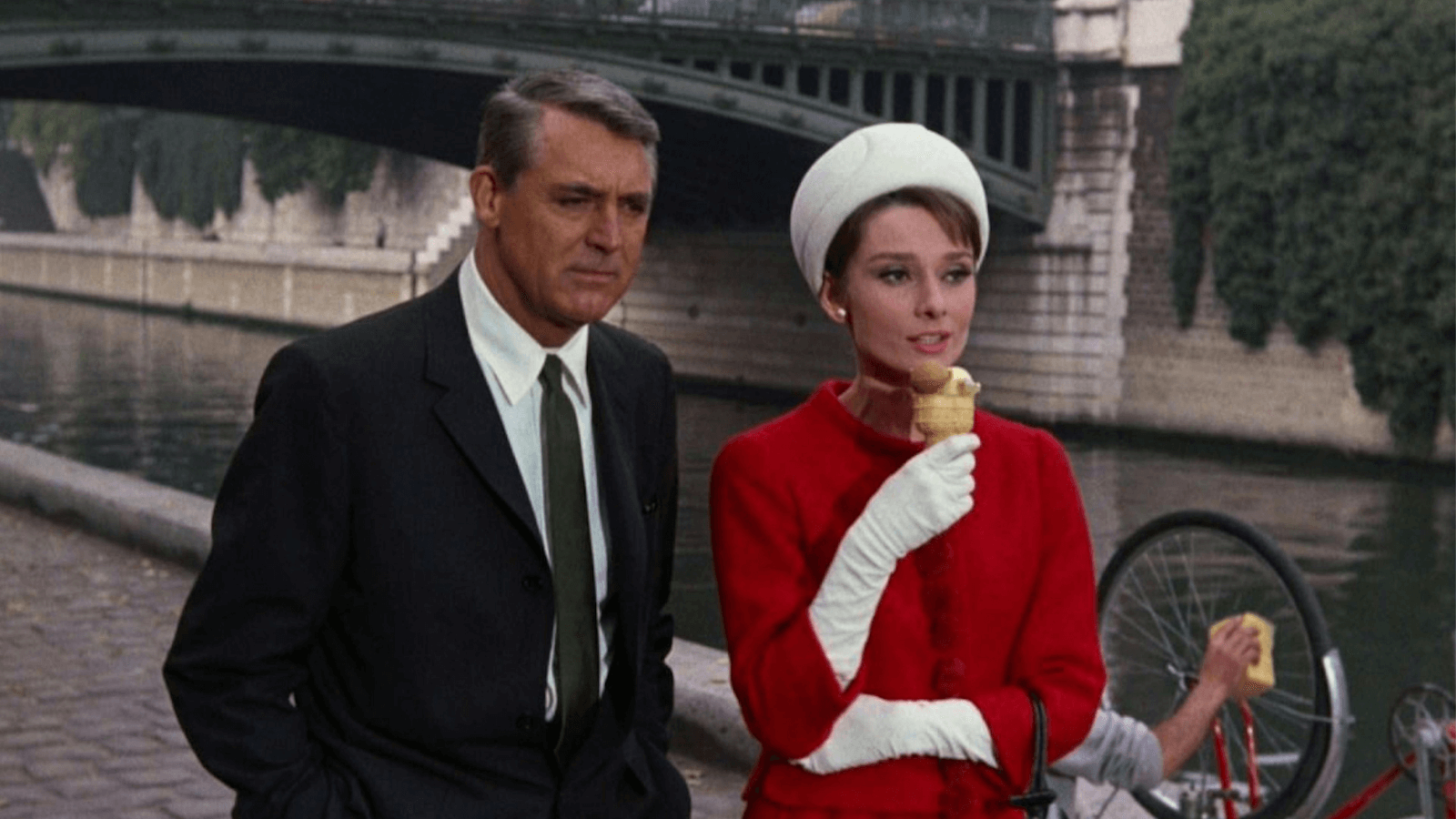

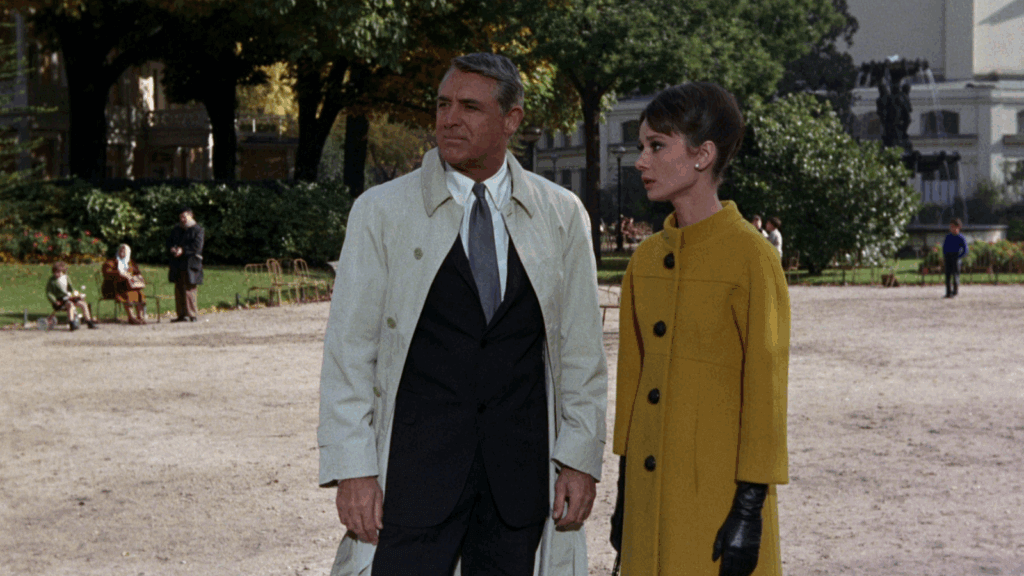

It’s almost a cliché at this point to call Charade the best Alfred Hitchcock film not directed by Hitchcock. Yet there’s an undeniable truth behind the claim. The 1963 film contains a veritable checklist of Hitchcockian tropes: a woman in trouble, mistaken identity, an elegant hero, a few murders, gorgeous scenery and costumes, and a blend of comedy and suspense. Although its scenario recalls a dozen or so Hitchcock pictures, its sharp dialogue and luminous stars—Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant—elevate this into a bright and shimmering bauble. Did Hollywood ever produce two icons who were more elegant and sophisticated, yet also accessible and charming? Their onscreen chemistry, coupled with a dangerous and delicious plot, makes Charade an essential piece of 1960s entertainment. Filled with memorable dialogue and a few hair-raising scenes, the film succeeds because Hepburn and Grant look so good and appear to have a great deal of fun together, despite their significant age difference of nearly a quarter-century. “I could already get in trouble for transporting a minor above the first floor,” jokes Grant’s character. But his reluctance makes their inevitable embrace all the more endearing. Whatever similarities one might find to Hitchcock and whatever questions one might have about the plotting disappear in the sheer bliss of watching Hepburn and Grant enjoy each other’s company.

Charade seems like an odd choice for director Stanley Donen, who was primarily known for directing musicals and lighthearted romances by 1963. Before Hollywood, he had a brief career as a stage performer and assistant stage manager. Then he started choreographing several MGM musicals alongside Gene Kelly, most famously Anchors Aweigh (1945). Within a few short years, he moved to co-directing alongside Kelly. They made Singin’ in the Rain (1952) together. Then Donen branched out into a solo career. Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954), The Pajama Game (1957), and The Grass Is Greener (1960) would follow, each demonstrating that he could adjust his style to the material while maintaining a vigorous onscreen energy and visual ingenuity. One of his finest touches comes in Indiscreet (1958), which features Ingrid Bergman as an actress who carries on an affair with a married, albeit separated man, played by Grant. Rather than place them in bed together—an illicit notion for 1950s moviegoers—Donen shows them on the phone, talking from their respective bedrooms. Juxtaposed together with split-screen, the two images create the impression that they’re sharing the same bed. It’s a trick worthy of Lubitsch. Indeed, Donen had a way of innovating on established styles and making them his own.

Watch the pre-credits scene in Charade; it feels like a Hitchcockian opener. A train passes by, and someone throws out a man in his pajamas. The victim tumbles down a steep hill and hits the bottom, where the close-up frame reveals his face, bruised and unquestionably dead. Then Henry Mancini’s jazzy, upbeat tempo arrives on the soundtrack, signaling the Saul Bass-esque titles in a swirling array of very 1960s shapes and colors. It’s like the opening of Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), except with a playful pulse. Then comes a decidedly macabre flourish, which signals Charade’s sense of humor: Audrey Hepburn’s Reggie Lampert, who’s hilariously always eating to calm her nerves, enjoys a meal in the French Alps. She does not yet know her husband, Charles, has died. Suddenly, an arm extends from behind a sun umbrella, and in the hand is a Luger pistol. Is she the next to die? It aims and fires, hitting Reggie square in the face with a stream of water. Throughout Charade, moments of suspense are offset by humor, usually in the form of Hepburn’s irresistible response. And this manner of creating tension, followed by a brief reprieve, only to create tension again, is a blueprint for Hitchcock’s most entertaining films.

Donen disliked the comparisons between Charade and Hitchcock. “Who said it was only Hitchcock who had the right to make mysteries?” wondered Donen. He told critic Stephen Harvey, “I just get a little annoyed at people thinking that he invented the comedy-adventure picture, or that he has a copyright on it. There have been plenty of comedy-adventures that have been good that aren’t Hitchcock’s […] I just don’t think he has the lock and key, that nobody else can touch something of this genre. That’s nonsense.” To be sure, Donen was not alone. Many directors had made similar films to Hitchcock’s before and after Donen. The most pronounced of them belong to Brian De Palma, whose series of features—Sisters (1972), Obsession (1976), Dressed to Kill (1980), Blow Out (1981), Body Double (1984), Raising Cain (1992)—splice various elements from Hitchcock classics into gristlier, hyper-sexualized films that bring to the surface many of the subtextual threads Hitchcock pictures. After all, Donen had gotten his start in musicals. And what are musicals if not a constant recapitulation of proven formulas? Comparing Charade to a Hitchcock picture, then, is less a slight against Donen than an acknowledgement of the tropes Hitchcock popularized and passed to those who followed.

But it’s not just the mystery or even the thrills that earn comparisons between Donen’s film and something conjured by the Master of Suspense. It’s also the humor. Charade bears a distinct playfulness around murder, and what’s more, corpses. There’s a ghastly and funny funeral sequence where the trio of villains—the bookish Leopold W. Gideon (Ned Glass), the sour Tex Panthollow (James Coburn), and the hook-handed Herman Scobie (George Kennedy)—check the body of Reggie’s late husband to ensure he’s dead. The scene is immediately comic. No one but Reggie, her friend Sylvie (Dominique Minot), and the investigating Inspector Edouard Grandpierre (Jacques Marin) have come to the funeral. Charles was not a well-liked man, and even Reggie barely knew him. Then, one by one, a trio of rogues arrives to ensure their former compatriot is dead. Gideon looks at the open casket and has a sneezing fit. “He must’ve known Charles pretty well,” quips Sylvie. “He’s allergic to him.” Tex enters next and holds a mirror up to Charles’ corpse to see if he’s breathing. Finally, Scobie storms into the scene and pokes Charles with a pin. When there’s no reaction, he tosses the pin and storms out again. Not since Hitchcock’s The Trouble with Harry (1955) had a dead body been the source of such a gag.

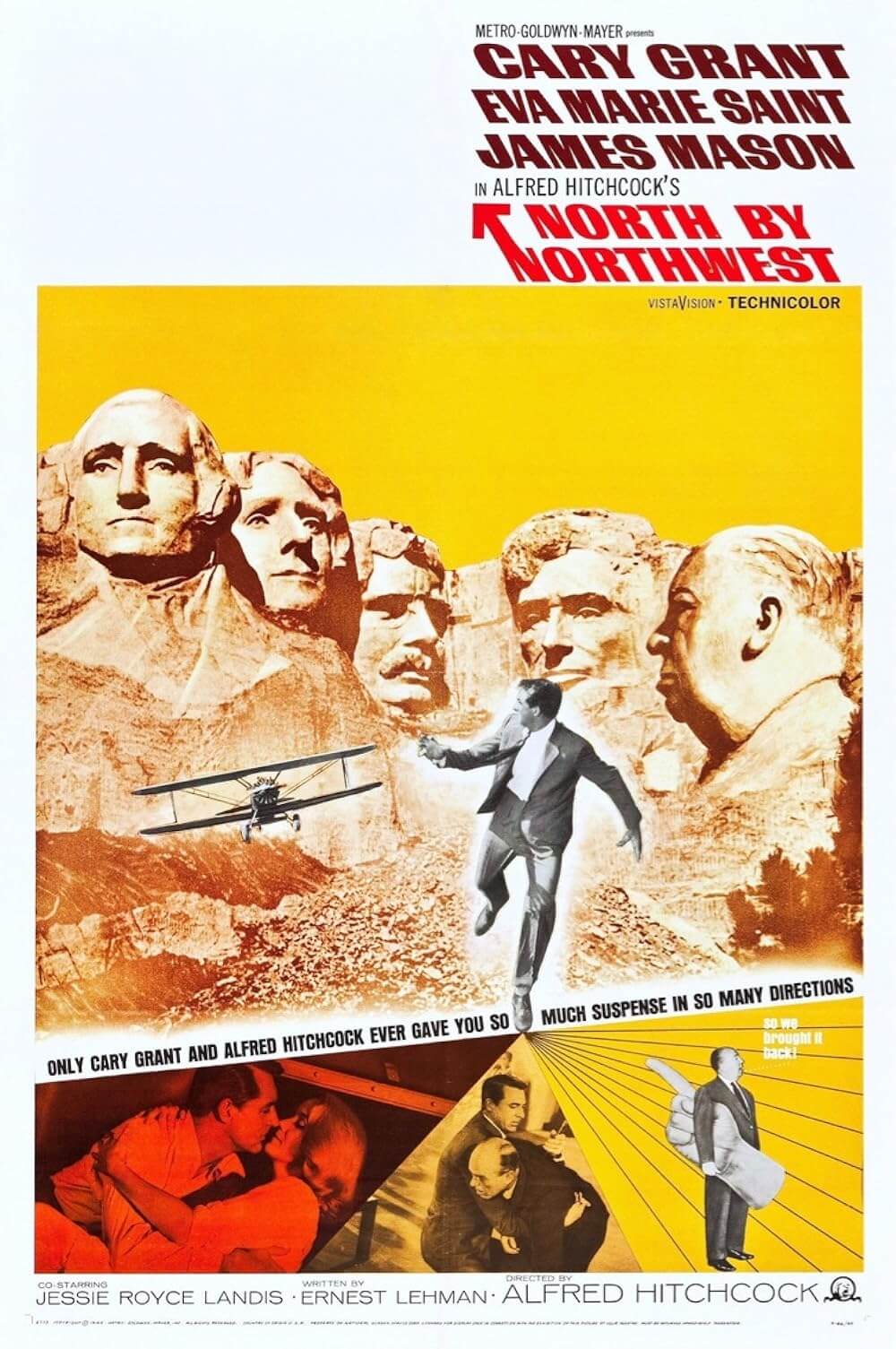

Charade takes other ingredients from the winning Hitchcock formula. For instance, Donen makes excellent use of actual locations, capturing a veritable guidebook of landmark stops in France, especially Paris, including Notre Dame, the Champs-Élysées, the Palais-Royal, and a ski resort in Megève in the French Alps. Hitchcock believed that landmark locations gave his films an innately iconic flair, and he used them regularly: the Statue of Liberty in Saboteur (1942); the Royal Albert Hall in both versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934, 1956); the Golden Gate Bridge in Vertigo; and the UN Headquarters, Grand Central Terminal, and Mount Rushmore in North by Northwest (1959). Then, of course, there was Cary Grant, considered by Hitchcock to be the perfect leading man. These ingredients blend into a delightful cocktail that tastes something like North by Northwest with a splash of To Catch a Thief (1955) and some The Trouble with Harry bitters. Donen admired North by Northwest, and the way Ernest Lehman’s screenplay presented Grant’s character as “somebody who didn’t exist. It’s a marvelous situation. That way, he could never prove that he wasn’t somebody who wasn’t alive.”

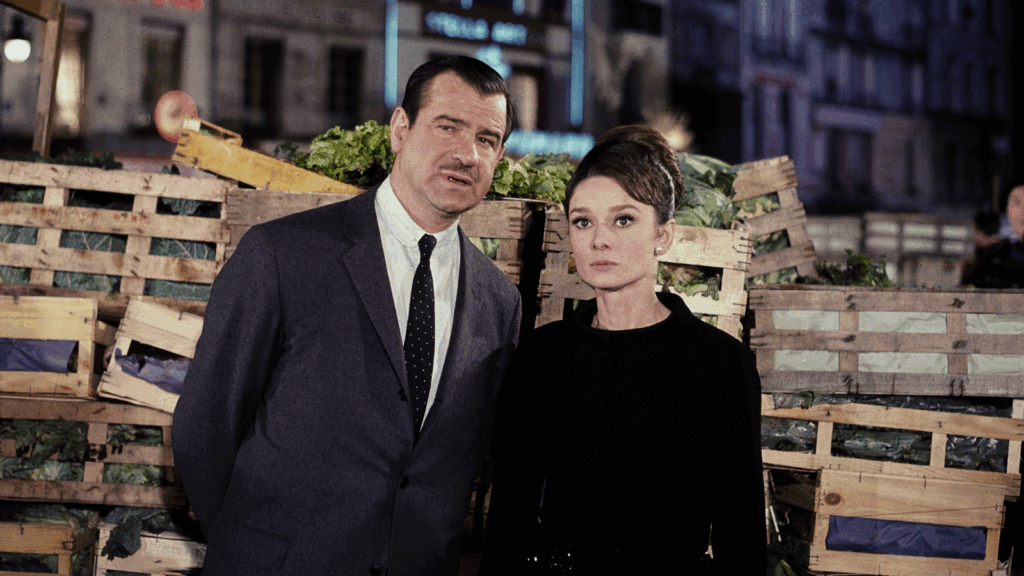

Something similar occurs in Charade. The story’s villains chase after Reggie because they think she has $250,000, which they stole during World War II before Charles took it for himself. But she doesn’t have it, at least not knowingly. Grant, under the name Peter Joshua, helps her navigate the mystery out of sheer kindness. But later, he will be known as Alexander Dyle, Adam Canfield, and Brian Cruikshank, and each identity comes with its own motivations (a protective brother, a master thief, a treasury agent). Reggie also receives intelligence from a CIA handler named Hamilton Bartholomew, played by Walter Matthau, who remains on the sidelines, squirreled away in his office at the U.S. embassy, eating liverwurst sandwiches. The villains close in, certain that Reggie has their money. Reggie falls for Grant, even as she learns of his false identities and questions whether she can trust him. But it’s Bartholomew she shouldn’t trust.

The scenario recalls Hitchcockian spy yarns about mistaken identity. In that sense, Charade is a wrong-woman thriller in the same manner as Hitchcock’s many wrong-man thrillers from The 39 Steps (1935) to North by Northwest. However, instead of the authorities chasing after a wrongly accused innocent, Donen’s film is about criminals pursuing Reggie, a wrongly targeted and clueless individual who cannot give them what they’re after. Each of the crooks is certain she has the money. At one point, Tex corners Reggie and threatens her by lighting matches and dropping them on her lap. We cannot help but wonder, why doesn’t she just blow them out? No matter. The knotty spy mechanics and occasional goofiness feel secondary to the burgeoning romance between Hepburn and Grant, who seem to play off their celebrity personas and admiration for each other. At one point, in the middle of an otherwise serious conversation, Hepburn touches Grant’s dimpled chin and asks, “How do you shave in there?” Watching the film, we’re distracted from the plot by Hepburn and Grant’s magic together, just as Reggie becomes so preoccupied by her affection for Peter-Alexander-Alan-Brian that she momentarily forgets about her dilemma.

Peter Stone wrote the novel, his first, called The Unsuspecting Wife, which was “really poor,” according to the author. Actually, Stone started out by writing a script, with Grant and Hepburn in mind for his two main characters, no less. His agent showed the script to several studios, but they rejected it. Stone was encouraged to write out the material into a short novel, which he did; it was subsequently published as a cheap paperback and then serialized in the pages of Redbook. Upon its publication, the bids immediately came rolling in; the studios wanted to adapt the same material they had rejected in script form. Although most of the bids came from Hollywood distributors, one came from a director. Stone signed with Stanley Donen because he had directed Hepburn in Funny Face (1957) and Grant in several pictures, and he wanted them for the picture. Donen had been working at Columbia at the time, and he arranged to get a $3 million budget with Grant and Hepburn attached to star. But Grant turned down the picture, saying he had another deal with Howard Hawks for Man’s Favorite Sport, and he was waiting for that script before he agreed to anything else. Hepburn was out if Grant was out, which left Columbia no choice but to downgrade the budget. Donen resolved to set up his own production company and arranged for Universal to distribute the film instead. He began searching for an alternative cast, and the studio suggested either Paul Newman or Warren Beatty alongside Natalie Wood. That’s when Grant contacted Donen and said he turned down the script for Man’s Favorite Sport after all (a role that went to Rock Hudson in 1964). It was bad timing. Columbia sued Donen for going to a competing studio with the Cary Grant project he had initially pitched to them.

Even after the legal snafu, Charade faced some additional challenges. Grant, 59 at the time, demanded slight changes to Stone’s script, downplaying the degree to which his character romantically pursues Hepburn, who was more than twenty years younger. The changes, with lines like “I’m old enough to be your father,” make it more apparent that Hepburn’s Reggie falls for Grant’s character and pursues him almost to the point of a Pepé Le Pew dynamic. (Never mind that Grant was dating Dyan Cannon at the time, and that she would become his fourth wife, despite her being 33 years younger than him.) Nevertheless, not even Grant’s protests could stop the May-December romance that remains so essential to the film’s allure. However, one change that did not occur involved Walter Matthau’s request to Donen: “I should be playing the Cary Grant part.” Matthau, who would develop a reputation for being difficult among certain directors, started his career playing sleazeballs and bad guys—he would not develop his comic persona until later in the 1960s, when he worked with Billy Wilder and Jack Lemmon. Needless to say, Donen didn’t take Matthau’s note. The most significant challenge for the production occurred when the United States and the Soviet Union brought the world to the brink of nuclear war in the Cuban Missile Crisis. Donen was so distraught that, as observed by his biographer Stephen M. Silverman, he announced to the cast and crew, “The world is going to blow up at any second, and here we are making a dumb movie.”

But the world did not end, and Charade is not a dumb movie. Rather, it was Donen’s biggest box-office success, and it features some terrific romantic banter and genuinely suspenseful moments. The violence, though, was too much for Universal. Even though Hitchcock could and often did get away with murder in his films, Donen had not yet proved he could successfully blend violence and humor in the same manner. The opening scene with Charles’ body tossed from a train, the various corpses throughout, and the breathless rooftop fight sequence between Grant’s character and Scobie, featuring a nasty slash from Scobie’s hook—these scenes compelled the studio to preview Charade, just to ensure it played well with audiences. After two preview screenings, the audience had spoken: the violence would stay in the picture. In reality, the audience had not spoken, at least not alone. Donen and Stone conspired to fill out preview cards themselves. When the card asked about their favorite part, they wrote, “When it’s violent.” When the card asked how the filmmakers could improve the picture, they wrote, “More violence.” Even so, the violence would be an issue for some critics, who questioned why a film about spies and murder had opened in early December, just two weeks after the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

The term “assassinate” was used a couple of times in Charade, and that proved triggering given recent events, setting off critics who used the film to decry the perceived increase of violence in cinema. Writing in the Saturday Review, critic Arthur Knight complained, “Our films and our television have made us so familiar with murder that we can laugh about it and shrug it away—until murder walks the streets and lurks in police corridors.” Bosley Crowther, in his review in The New York Times, noted the “grisly touches” in an otherwise positive review. But many critics enjoyed Charade and its romantic escapism. The review in Variety acknowledged the film had “several moments of violence but they are leavened with a generous helping of spoofery.” Judith Crist, who appeared regularly on the Today show and wrote for The New York Herald Tribune, hailed its “grown-up, tongue-in-cheek romance” and compared the result to a Christmas gift. In Pauline Kael’s review in The New Yorker, she called it “probably the best American film of last year—as artificial and enjoyable in its way as The Big Sleep.” That’s an apt comparison to Howard Hawks’ famously inscrutable thriller. Charade, too, has a zig-zagging plot that, in due time, reveals multiple identities for both Grant and Matthau’s characters, along with a clever resolution involving a stamp collection.

Charade was such a hit that Universal wanted to duplicate it, and they compelled Donen to produce and direct another zippy romantic thriller co-written by Stone. Arabesque was based on a 1961 novel called The Cypher by Alex Gordon. Julian Mitchell and Stanley Price penned the initial drafts, and Stone was hired to punch up the dialogue. Stone, credited under the pseudonym Pierre Marton, rewrote the script, but Donen was indifferent toward the picture even after the revisions. Grant wasn’t interested either, even though Stone had written the leading man part for him. The film, which once again placed an older gentleman with a younger woman, would star Gregory Peck and Sofia Loren. Arabesque, a title suggested by Peck, also bears a resemblance to Charade for its dizzying opening credits sequence, its blithe attitude toward spy games and murder, and its sheer bankability. It would go on to earn profits, but its $5.8 million at the box office was paltry compared to Charade’s more than $13 million. There was no replicating the magic that Grant and Hepburn brought to the screen.

The 1960s saw a strain of similar comic thrillers, most of which drew from the works of Ian Fleming and spy yarns directed by Hitchcock, especially North by Northwest. Everyone wanted something similar, resulting in many variations on a theme. When they set out to make Dr. No, producers Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman tried to convince Cary Grant to play James Bond, hoping to capture the debonair magic of his character, Roger O. Thornhill. But Grant turned down the role. Sean Connery took over and proved in 1962 that a more violent brand of spy story appealed to viewers. Charade emerges from this spy soup, although its differences remain notable. To begin with, the story does not revolve around a man. The audience follows Audrey Hepburn through dizzying twists and turns, hinted at by the animated titles, as the only character not playing at some elaborate deception. Grant’s character remains on the periphery, and with few exceptions, the film features few scenes with Grant and not Hepburn. She drives the story and the romantic tension as well, even if she too easily fulfills the trope of a helpless, childlike woman who needs a man to rescue her. Hepburn often played these roles: she was rescued by Gregory Peck in Roman Holiday (1953), Humphrey Bogart in Sabrina (1954), and Fred Astaire in Funny Face.

But unlike James Bond, Charade’s protagonist does not make everything look easy, especially when it comes to romantic conquests. Despite her classy wardrobe by Givenchy, Reggie is awkward, a nervous eater, and occasionally clumsy, leading to a forced moment when she plunges an ice cream cone into Grant’s suit. Hepburn’s pursuit of Grant has the quality of a Lubitsch romance, relying on subtle innuendo and humor. The sole exception is a sequence in a Parisian nightclub where they play “Pass the Orange.” What starts as a humorous scene where Grant rubs against a large, bemused woman overflows with sexual tension when Hepburn and Grant maneuver their bodies against each other, and it’s enough to spark something in Reggie. This scene aside, their playful interactions demonstrate a chasteness more often associated with Classic Hollywood titles as opposed to the new liberties given to films in the 1960s. When Reggie first meets Grant’s Peter Joshua, their exchange is lively and flirtatious. “Is there a Mr. Lampert?” he asks. “I’m getting a divorce,” she replies. “Please, not on my account,” he quips. Stone’s screenplay features numerous magnetic exchanges like this, reminiscent of the romantic repartee in some of Grant’s films with Hitchcock, such as Notorious (1946), To Catch a Thief, and North by Northwest.

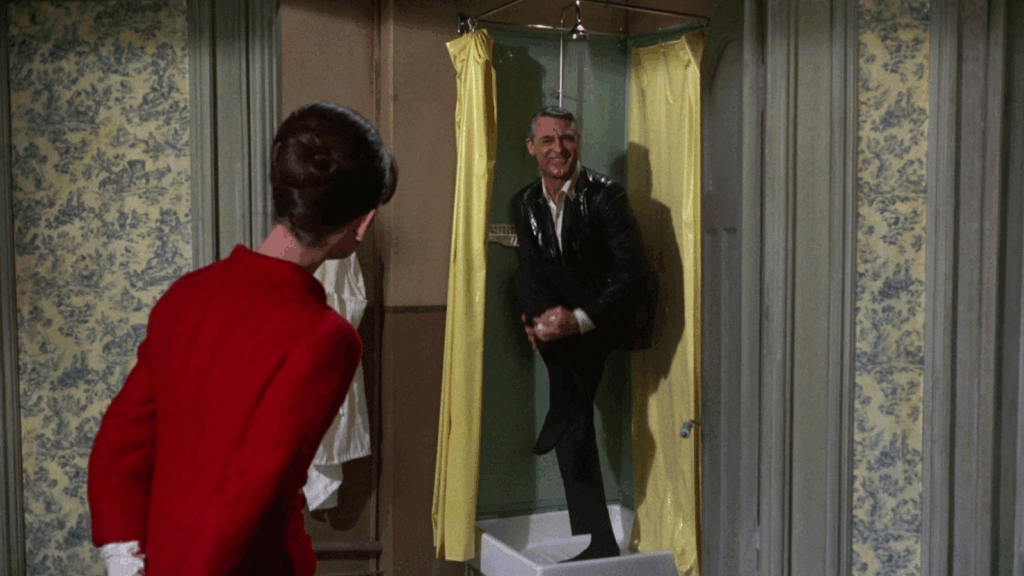

In Charade, like those Grant-Hitchcock films, the dialogue leads to the inevitable moment where the leading man’s reluctant lover finally acquiesces, except it’s the other way around—Grant acquiesces. And not unlike another Lubitsch-inspired romance starring Hepburn, Billy Wilder’s Love in the Afternoon from 1957, where she was paired opposite Gary Cooper, the May-December relationship in Charade works somehow. They’re wrong for each other in a way, but they’re also so right together. However, their chemistry was not just the natural result of two charming stars appearing together. Donen worked with them to rehearse and coordinate each interaction. “There’s nothing improvised in the film,” the director told Film Comment in 1973. “It’s all been worked through and rehearsed and planned and thought about and regurgitated. But still, the word improvisation is a very strange word because everything initially is improvised, it has to start somewhere but you still consider it a while because you put it out.” Take the scene when Reggie screams in terror, only so Grant’s character will come to her rescue—she’s afraid to be alone. When he rushes to her room, she locks him inside and insists he use her shower (they just found Scobie’s corpse in his tub). Rather than disrobe in her room, he removes his shoes, and takes a shower in his “drip-dry” suit. The silliness of the moment feels spontaneous, as though Grant made the choice at random. Certainly, Hepburn’s reaction seems naturally shocked and amused. In truth, Grant protested the scene, and Donen had to convince him to perform it. Moments like this give the film its splendid magic.

Hepburn and Grant make Charade feel effortless, and because of that, Donen jolts his unsuspecting audience with the occasional chilling image or shock. Note the shot from inside a morgue drawer, how Scobie ends up drowned in a bathtub, or how Tex winds up smothered with a plastic bag. When most of the film entails Hepburn and Grant having a good time together, these macabre details catch us by surprise, even upon rewatching it. Still, the stars leave the plot secondary and render the film’s few flaws (for instance, Reggie refers to herself as an American living in Paris, despite Hepburn’s British accent) negligible. And anyway, it’s impossible to hold anything against a film that feels so blithe. Charade marks the last great film in Grant’s career; he would retire a few years later. Hepburn would continue acting into the 1980s, but she was rarely more dazzling than in her appearance opposite Grant. The film does not offer social commentary or entrenched themes. It’s just entertainment, assembled with class and brimming with glamour and charm. Whether it’s the Hitchcockian touches, the constant laughs and thrills, or the blissful pairing of the two leads, Charade continues to delight and reward each new viewing, confirming its status as an escapist classic.

(Editor’s Note: This essay is an expansion of a review published on September 13, 2020, which was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Elizabeth!)

Bibliography:

Harvey, Stephen. “Stanley Donen. Interviewed by Stephen Harvey.” Film Comment, vol. 9, no. 4, 1973, pp. 4–9. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43450622. Accessed 2 September 2020.

Paris, Barry. Audrey Hepburn. Berkley; Reissue Edition, 2001.

Schickel, Richard. Cary Grant: A Celebration. Little, Brown, 1983.

Silverman, Stephen M. Dancing on the Ceiling: Stanley Donen and His Movies. Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review