The Smashing Machine

By Brian Eggert |

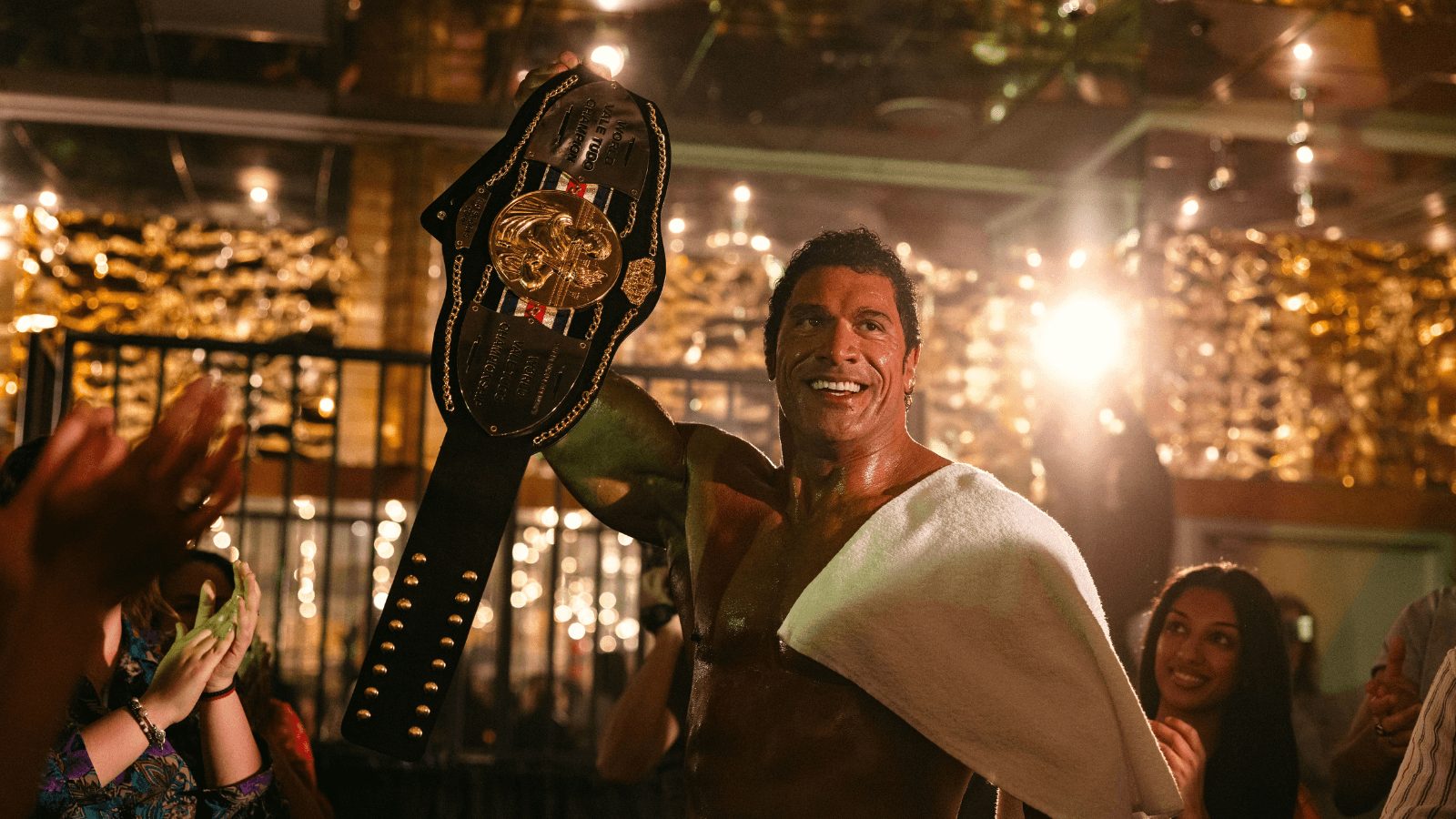

A Japanese journalist asks, “Sometimes, we lose. What would that feel like?” Mark Kerr doesn’t have an answer. He has never lost. After getting his start in Brazilian mixed martial arts, the Toledo-born fighter transitioned to Japan’s Pride Fighting Championships for the money. He made a name for himself as an unstoppable force well before the UFC became a billion-dollar industry that exploded a few years after Mark’s heyday. And shortly before a monumental bout at Pride 7 in 1999, he answers the question about losing with a confused but polite smile: He can’t imagine it; he doesn’t have any context for something like that. Played by Dwayne Johnson in an Oscar-baiting performance, Mark is the eponymous character in The Smashing Machine, written and directed by Benny Safdie, who takes a break from working alongside his brother Josh on his first solo effort. Safdie tells a familiar story in the sports movie mold, recalling greats of the genre from Rocky (1976) to The Wrestler (2008). But apart from committed performances throughout, the director remains too dependent on his source material to call the movie original or even memorable.

Safdie based his screenplay on John Hyams’ 2002 documentary for HBO, The Smashing Machine: The Life and Times of Extreme Fighter Mark Kerr. He lifts entire scenes and dialogue passages from the documentary verbatim, such as when Kerr explains MMA to a woman in a doctor’s office—a scene that the distributor A24 highlights in the film’s marketing. Safdie replicates Mark’s interactions with journalists, his relationship with his longtime girlfriend, and the fights to the smallest detail. Even Mark’s kitchen looks identical. Safdie follows an unfortunate trend of narrative dramas based on documentaries: The Walk (2015) was based on Man on Wire (2008), Welcome to Marwen (2018) was based on Marwencol (2010), and The Eyes of Tammy Faye (2021) was based on a 2000 documentary of the same name. And while it’s certain to earn awards buzz for Johnson, it feels like a safe and commercially viable departure from the Safdies’ recent nerve-racking thrillers, Good Time (2017) and Uncut Gems (2019).

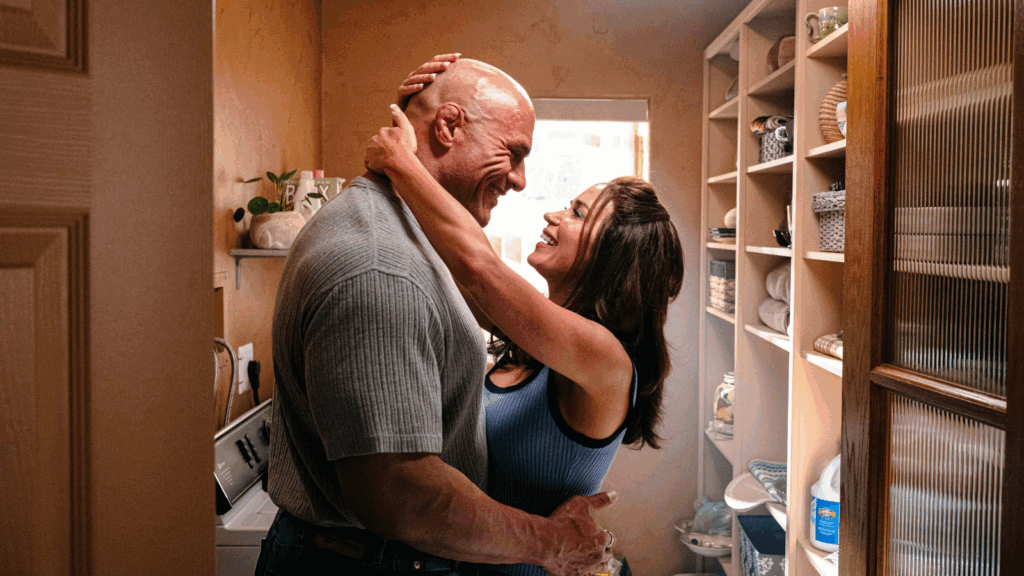

For those unfamiliar with the doc, the story follows Mark’s rise from 1997 to 2000. A gentle giant whose job involves pummeling his opponents into a bloody pulp, Mark must look inward after losing a match to Igor Vovchanchyn (Oleksandr Usyk). He receives little encouragement from the self-obsessed Dawn (Emily Blunt), who contributes to their rocky relationship with a volatility that distracts Mark not only from his fights but also from his addiction to painkillers, which lands him in treatment. After getting clean, he rejoins the circuit with the help of his coach (Bas Rutten, playing himself) and best friend Mark Coleman (MMA star Ryan Bader), a fellow fighter with whom he maintains an endearing, supportive relationship. Dawn’s “You’re no fun anymore” response to Mark’s recovery hardly welcomes sympathy for her in Safdie and Blunt’s treatment of the character. Even as Mark makes the requisite comeback, complete with the obligatory training montage, the story is less about Mark fighting for glory than getting control of his life. However, the anticlimactic conclusion isn’t the Balboa-style victory through loss; it’s more about Mark realizing that he’s not invulnerable, and his identity remains a work in progress.

Safdie’s unabashed recreation of moments from the documentary diminishes their impact, whereas filmmakers such as Robert Zemeckis, in the other examples of this doc-to-drama trend mentioned above, use the freedom of narrative storytelling to explore something more cinematic. Instead, Safdie and cinematographer Maceo Bishop apply a docu-drama aesthetic, with shaky and grainy camerawork that gives the viewer a really-there feel. It’s almost as though Safdie’s camera belongs to a never-acknowledged documentary crew off-screen, and his film is a drama about the making of Hyams’ doc. Given their similarities, one wonders about the artistic impetus driving The Smashing Machine, whether it’s an homage through imitation, a means to garner awards consideration for Johnson, or both. Whatever the reason, there’s a frustrating sameness to his film that’s disappointing.

Elsewhere, Safdie makes ham-fisted choices, including a common one for sports movies. During the fight sequences, disembodied announcers dump exposition about what’s happening in the ring and what Mark must be feeling at that moment. Safdie doesn’t trust the viewer to imagine Mark’s mental state through Johnson’s performance, so he punctuates the scene with sportscaster commentary. The music choices, too, have unmissable meaning. The score incorporates the psychedelic sounds of the Safdies’ last two efforts, complemented by experimental musician Nala Sinephro’s electronic jazz and drums, which echo the improvisational mode of MMA fighting. That detail is preferable to Safdie’s obvious song choices. Take when Mark injects opioids into his arm against Lil Suzy’s “Take Me In Your Arms,” with the lyrics “I need you more and more” to suggest his addiction. Or when, due to a sensitive tummy, Mark prefers to ride a carousel rather than join Dawn on a dizzying carnival ride, while Jon Secada sings “Just another day without you.” And, inevitably, Safdie resorts to Sinatra’s “My Way” to show Mark’s journey of selfhood.

With Johnson serving as producer and working alongside his Jungle Cruise (2021) costar Blunt, it’s impossible not to see The Smashing Machine as an attempt to establish the wrestler-turned-action-hero as a serious actor. For his part, Johnson never quite disappears into the role; however, he portrays a range of emotions behind some distracting brow prosthetics, a sensitive voice, and a lumbering yet delicate demeanor. It’s apparent from watching the doc or footage of the real Mark Kerr that Johnson did his research, but this isn’t one of the great transformations in acting history. Still, here’s hoping Johnson continues flexing his acting muscle in more than his standard tough-guy roles. At the same time, Blunt feels wasted in a thankless part where she has little to do besides nag, complain, and escalate every scene. Somehow, the most endearing performance belongs to Bader, whose side story could be a sports movie unto itself.

The Smashing Machine attempts to tie Mark’s story in a bow with a subplot about the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, wherein beauty lies in imperfections, in broken objects that have been repaired. The symbolism becomes unmistakable when Mark buys Dawn a decorative bowl in Japan, only for her to shatter the gift during one of their fights. She later repairs it, vaguely explaining the concept. What might’ve been an understated literary symbol turns into a dumbed-down thesis statement. It’s another in a long line of embellished details that make the film less of a readable experience than a surface-level exercise in melodrama. Although Safdie’s admiration for Mark remains potent, and if viewed in a vacuum without the doc as context, The Smashing Machine might register as a worthwhile variation on the sports movie template, there’s little to distinguish the material beyond the showy performances at the center.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review