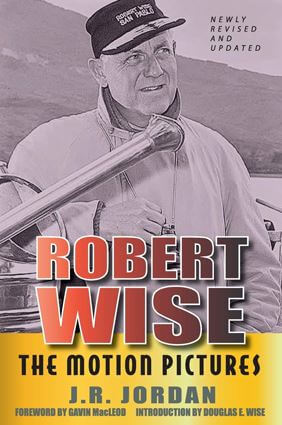

“Robert Wise: The Motion Pictures” by J. R. Jordan

Author: J. R. Jordan

Author: J. R. Jordan

Published: BearManor Media, February 8, 2020 (Revised Edition)

Order from Amazon

The idea of the director as a film’s author has countless exceptions. Plenty of film writers and cultural commentators have poked holes in Andrew Sarris’ original argument that directors have personal visions and obsessions, the evidence of which amounts to a traceable pattern throughout their work and a richer form of cinema. Detractors note how the auteur theory ignores the contribution of screenwriters like David Mamet or Aaron Sorkin, and it fails to adequately consider mogul producers like David O. Selnick or Steven Spielberg. It also ignores that filmmaking is a collaborative effort, a procession of sometimes happy accidents that emerge from organized chaos. Still, plenty of evidence can be found in support of the auteur theory, given that directors often devise plans and then oversee the cooperative effort of artists who help to realize the director’s intent. Despite all the counterarguments and departures, someone like Robert Wise challenges the auteur theory’s notion of what makes a great director.

In his book Robert Wise: The Motion Pictures, author J.R. Jordan explores Wise’s career as a director in Hollywood, starting in 1944 with his early work at RKO alongside producer Val Lewton and ending with a Hallmark movie penned by Rod Serling in 2000. Over the course of his fifty years in Tinsel Town, Wise transitioned from the editor of Citizen Kane (1940) to the winner of Oscars for Best Director of West Side Story (1961) and The Sound of Music (1965). Jordan’s newly revised and updated book is an easy sell to fans of Wise’s other landmarks, including The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), Executive Suite (1954), and Run Silent, Run Deep (1958). And while I, too, appreciated how much attention that Jordan gives to many of Wise’s best-known and most-celebrated titles, I preferred the author’s clear affinity for cherished B-movies: the macabre The Body Snatcher (1945), starring Boris Karloff as a grave robber; Blood on the Moon (1948), a moody Western with Robert Mitchum; and the real-time boxing noir, The Set-Up (1949).

When so many books about directors are auteur studies, it’s refreshing to find one that considers the work of a journeyman on a film-by-film basis. After some opening remarks that set the stage of Wise’s career in Hollywood, Jordan’s method considers each film individually, offering a comfortably consistent and accessible approach. He includes remarks about each project’s development, followed by close readings of the story and Wise’s treatment of it, while also interweaving a historical overview of the production and its reception throughout each chapter. If the earlier entries feel lighter due to the lack of available interviewees, the latter half of the book provides much insight from those who worked alongside Wise. Jordan interviews performers, stunt people, and several below-the-line collaborators from Wise’s films. These first-hand accounts add much to the usual production histories and our appreciation of Wise himself. The author also includes a few brief quotes from the critics at the time of a film’s release, though these are mostly the positive assessments; the pans and dismissals of Wise’s lesser films are seldom addressed.

That word I used earlier, journeyman, is often used as a pejorative by certain cinephiles who value the voice of a singular artist over that of someone like Wise. To be sure, many of Wise’s projects, as Jordan’s historical investigation into each film reveals, amount to direct-for-hire jobs. When he makes A Game of Death (1945), a remake of Richard Connell’s short story “The Most Dangerous Game”—which had already been adapted into a fine adventure by Irving Pichel and Ernest B. Schoedsack in 1932—it’s because the studio had a valuable intellectual property and needed a programmer delivered on budget. Perhaps it goes without saying that Wise could adapt to the situation handed to him. Even so, he developed enough clout so that, when he read the original story that was the basis for The Haunting (1963) in Time magazine, he could pitch it to MGM and get it made, delivering an all-time classic in the process. Wise’s career survived the slow demise of Hollywood’s studio system. His The Sound of Music is often cited by historians as the last true classic of the old regime. Still, he flourished in his later years with hits like The Andromeda Strain (1971) and Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). Jordan reveals that the key to Wise lasting was his even temper and willingness to compromise.

Not so much a purely biographical text, like so many pieces by Joseph McBride or Patrick McGilligan, Robert Wise: The Motion Pictures is not a close accounting of the events in Wise’s life. Jordan concentrates on the work, which is true of Wise as well. More than once, the interviewees use words like “relaxed” and “easy-going” and “collaborative” to describe him. In the book, you won’t find Wise engaged in salacious behind-the-scenes clashes or heated creative arguments with actors or studio executives. He’s an even-keeled personality, far from the volatile and control-freak personality type that we often associate with auteurs. In the most basic sense, which is implied by the structure of Jordan’s book, Wise gravitated toward good material, whether it was presented to him or he discovered it. He aimed to tell good stories in an unpretentious way. About screenwriters, Wise said, “I felt I owed it to the audience to faithfully bring their fine work to the screen to the best of my creative powers.” He also believed in audience previews to hone his films, a trait not common among auteurs, but a process deemed necessary by filmmakers ranging from Harold Lloyd to Ron Howard. Jordan’s book shows how Wise worked in a selfless way, delivering memorable films that audiences continue to discover and treasure.

Gavin MacLeod, who came to think of Wise as a father figure, supplies a touching foreword to the book, suggesting just how strong an impression Wise made on those who worked with him. Indeed, it’s easy to see what MacLeod, thus Jordan, admires so much. Robert Wise: The Motion Pictures is a generous appreciation of a versatile Hollywood craftsman, a figure who belongs on a list of dependable filmmakers like Michael Curtiz, Raoul Walsh, and William Wyler. Such names are not often the subject of auteur studies, but they have made an indelible mark on film history and demand to be investigated. Wise could be thought of as a studio worker bee, but his honey, tasted on films from The Body Snatcher and The Sound of Music, was sweeter than most. Jordan’s book has a clear affection for Wise and his wide range of work in Hollywood, which will appeal to anyone versed in reading director biographies. The book showcases a consummate professional, and Jordan’s well-researched summaries of each film offer a loving celebration of Wise’s impact on cinema.

Addendum:

Addendum:

The book is dedicated to the author’s father. Joseph C. Jordan Jr. suddenly passed a short time following the publication of this book review. In Robert Wise: The Motion Pictures, the author wrote, “Those I interviewed for this book generally described Robert Wise as noble, patient, validating, and a class act. Such words, in short, apply to Dad.”

Schoedsack in 1932—it’s because the studio had a valuable intellectual property and needed a programmer delivered on budget.