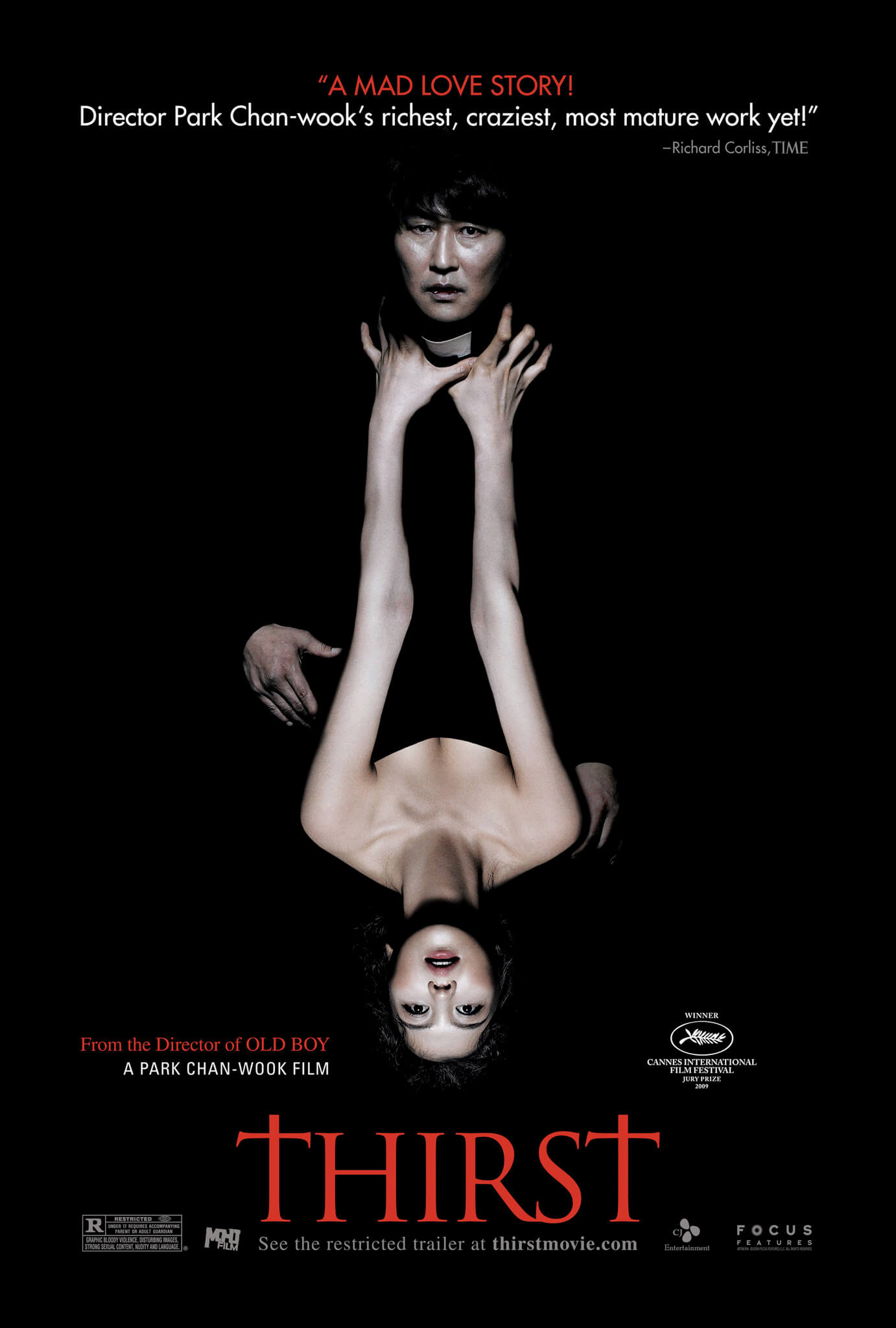

Thirst

By Brian Eggert |

A lyrical balance of conscience, sadism, and romance, Park Chan-wook’s Thirst (Bakjwi) weighs the ongoing battle between intellect, conscience, religious morality, and carnal hunger for the flesh. The South Korean director of Oldboy uses violence and sex-like poetic descriptors to construct yet another drama worthy of Greek tragedy, a smolderingly sensual and graphic picture of the potency of desire. Inspired by Emile Zola’s novel Thérèse Raquin, the film considers the recurrent Zola theme of the La Bête humaine, meaning the human beast. Park simply investigates humanity by making his film’s beast a vampire. Unlike typical cinematic depictions of this increasingly overexposed movie monster, the film addresses the problems inherent to vampirism.

Whereas franchises like Twilight and Underworld use the monster’s form as a metaphor for chastity or social displacement, Park delves into the potential reality of vampirism, and then he considers its grave implications. What are vampires about if not blood and sexuality, and what part of humanity remains when existence is reduced to such extremes? Park asks these questions so that when his film’s protagonist, a priest, a man wholly dedicated to the idea of self-restraint, suddenly finds himself overflowing with heightened cravings, the potential for existential contemplation and drama is limitless. Park taps a direct line into his premise and explores it fully, going in directions the viewer will not expect him to.

Star Song Kang-ho plays Sang-hyun (Is it a coincidence that “Sang,” or derivations thereof, means blood in the romance languages?), whose duties as a Catholic priest do not deter him from believing in the sciences. Along with so many Hail Marys, he tells a woman in confession to accept God’s help through science and take anti-depressants. Volunteering at a hospital, he sees the destruction caused by an infectious disease called the Emmanuel Virus, and being dismayed with the suffering it inflicts, he offers his body to research to test potential vaccines. During his clinical trial, a test vaccine affects his blood and leaves him in a vampiric state. At first, he breaks out in blisters, coughs blood, and appears to die. But he’s not dead. In fact, he slowly grows stronger, healthier, and better. His recovery is publicized and people call him “The Bandaged Saint,” as he keeps his face wrapped in a dressing to hide the remaining blisters. And yet, when he tastes blood, his blisters disappear.

Sang-hyun’s senses go wild and grow more attuned, his thirst for blood growing along with them. Sunlight begins to burn his skin, so he sleeps through the day in a closet. He still visits the hospital to fulfill his priestly duties, but he uses a coma victim there as a source of blood, drinking straight from an IV hooked into the patient’s vein. Killing is not an option. His blind mentor at the church, also a priest, will not let his son take the lives of others and, instead, he offers his blood to stave off Sang-hyun’s longing. A fangless vampire, Sang-hyun struggles to control sudden impulses, his bodily aches for blood and lustful thoughts—and the last remnants of his faith send him into self-flagellation at the thought of sex. Those remnants all but disappear when his mentor asks to be turned, if only so that he may see again. Sang-hyun renounces his faith at the thought of subjecting someone else to his curse.

Sang-hyun’s little problem is especially difficult around Tae-ju (Kim Ok-bin), the wife of his childhood friend Kang-woo (Shin Ha-kyun), who makes her attraction to him clear. Treated like a dog by Kang-woo’s live-in mother, Lady Ra (Kim Hae-sook), Tae-ju makes Sang-hyun feel as though an affair would be rescuing her from her abusive family. But there’s also a level of fetishist sadism with her, as she’s more attracted to the virginal Sang-hyun because he’s a priest. She also seems to take pleasure from pain—she revels in inquisitive ecstasy at his bites when they first make love, asking, “Am I some kind of pervert?” And though hesitant when Sang-hyun confesses his true nature, she later jumps at the idea of vampirism. Soon their relationship electrifies with sexuality and bloodlust, and when he turns her, she completely embraces her animalistic desires such as killing, while he remains split between what lingers of his spiritual self and the monster inside.

Darkly comical in its macabre manner, the film is funny, romantic, horrifying, and saddening all at once. Park views his subject from a unique perspective. He incorporates religious symbolism to deepen Sang-hyun’s predicament (consider when Sang-hyun slices open his own stomach so his mentor can feel inside, echoing St. Thomas the doubter), along with a substantial set of principles that make his character dynamic, particularly when placed next to the scenes of vampire violence. These characters have several dimensions, and the actors convey that amazingly. Song, with his stoic yet charismatic expressions, has been a staple of South Korean cinema for years, starring in blockbusters like The Host and The Good, the Bad, the Weird. But newcomer Kim steals the film; her complicated, kinetic performance crackles with passion, both in terms of her rapture and murderous delight.

So few films about vampires acknowledge the monster’s dilemma of existence as their central conflict. Vampires are often the garnish to a plot about something else entirely. Most are little more than gory monster movies, such as 30 Days of Night or From Dusk Till Dawn. The highly acclaimed Let the Right One In used vampires as an allegory for teen angst. Even the original Dracula, or Francis Ford Coppola’s wonderful remake, concerned vampires as monsters hiding in the darkness, but never confronted them directly. Only truly daring filmmakers such as F.W. Murnau and Werner Herzog with their respective Nosferatu pictures, or Neil Jordan with Interview with a Vampire, have explored the world and innate pain of being a vampire. Park’s film tops them all, as it seems to be exploring the vampire world versus simply accepting the formulas that have been passed down through hundreds of movies, books, and TV shows about them.

To anticipate anything less than something provocative and insightful from Park would be a mistake, however. His films always use challenging material to make profound observations, and they have a strange way of using a substantial amount of blood and sex without being tasteless. From his box-office hit JSA: Joint Security Area to his Vengeance Trilogy (Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, Oldboy, and Lady Vengeance) to his blithe, underseen romance I’m a Cyborg But That’s OK, Park’s films are not what you would call subtle. He’s known for his vivid portrayals of violence and sexuality. But curiously, his films are always thoughtful and never gratuitous, even though they may be shocking and perverse to some. There’s always a sharp, surprising resonance to his storytelling, making his films irresistible and exciting viewing.

Throughout the film’s very audible kissing and slurpy blood-drinking, it proves to be scary, remarkably moving, and startlingly evocative. And like most Park films, it doesn’t end when the audience expects it to. The final section of Thirst transforms the characters and retains their humanity, even amid the most frenzied embrace of their obsessions. Park’s film is an ingenious look at a sleepy topic, proving that the vampire movie hasn’t lost its verve but that most directors making them have. Place a filmmaker like Park behind the camera and suddenly the genre awakens from its slumber, digs itself from out of its own grave, and emerges ready to feed from the ideas of a great director. Over time, Thirst will no doubt be considered one of the best vampire films ever made.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review