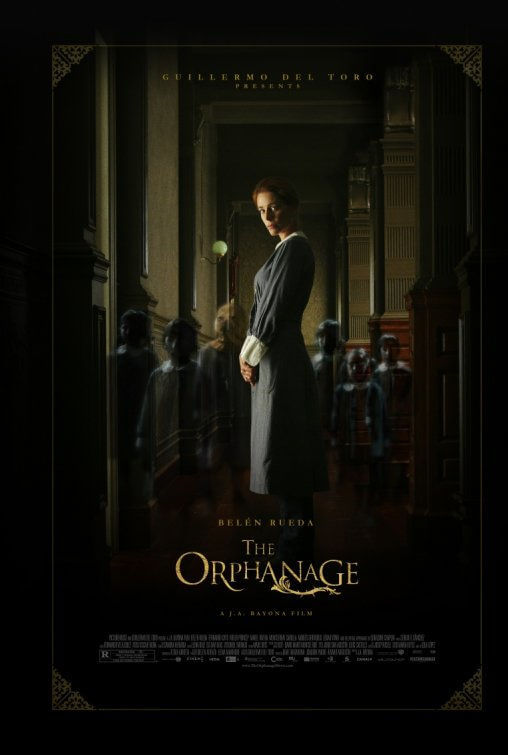

The Orphanage

By Brian Eggert |

What is it about children’s games that are at once innocent and yet interminably creepy? Perhaps it’s how children, in horror movies anyway, always sing nursery rhymes or the passage to their favorite game at a malevolently slow pace. In The Orphanage, the repeated phrase, which sent the hairs on the back of my neck shooting up, was “One, Two, Three… Knock on the wall.” Each time this passage is said, the player’s back is turned, and then she looks back to see that, with her counting, the other children behind her have moved closer… closer… closer. Who can say what the children will do when they reach her? It’s moments like this that make first-time Spanish filmmaker Juan Antonio Bayona’s movie superior to the average ghost story. It relies on anticipation more than special effects or jump-scares. To be sure, Bayona displays incredible promise in how he works with cinematographer Oscar Faura to bend and swerve the camera in a way that cleverly limits what we see when, all the while, we’re frightened as hell by what we’re not seeing.

The story begins with Laura (Belén Rueda), a woman returning to her childhood orphanage to reopen its doors with her husband, Carlos (Fernando Cayo), turning it into a home for disabled children. Their adopted son, Simón (Roger Príncep), who doesn’t know he’s adopted or that he has a terminal illness, joins them. Though a lonely place for a child, Simón finds imaginary friends to play with in his new home. His parents suspect they’ll disappear when the other children arrive. Laura, who spent her childhood within those walls, even indulges his fantasy, understanding adolescent loneliness. Laura realizes her mistake in due time when Simón suddenly disappears. She begins to suspect these “imaginary” friends. Are they ghosts? Is there someone living in the orphanage?

Perhaps she should ask Benigna (Montserrat Carulla), a supposed social worker who came about the day before Simón’s disappearance, asking questions about his progress. No doubt Benigna is suspect when Laura finds her snooping about their backyard in the twilight. And what does any of this have to do with Laura’s time there as a child? I suppose it doesn’t matter, since this is a movie about suspense, not plot—and that’s a good thing, as some of the twists and turns (particularly the film’s final scenes) are unsatisfying. Instead, look at the tension created by Bayona with eerie images of Tomás, Simón’s new imaginary friend, a childlike figure sporting a decrepit sack over his head. Laura spots the creepy, maybe real, maybe supernatural child and realizes that somehow, Simón’s disappearance involves the orphanage, her past there, and, indeed, something more sinister.

The Orphanage’s opening credits include the deceptive “Guillermo del Toro Presents,” so audiences not knowing any better might think the Pan’s Labyrinth director actually had a say in the creative process. Perhaps he did, but perhaps not. Some producers involve themselves in every aspect of a film, while others simply allow a director his or her freedom. David O. Selznick used to demand control over every detail, every casting decision, every costume choice, right down to what colors should be prominent in a specific shot. Every interview or commentary I’ve seen with Del Toro shows him to be a pleasant, non-intrusive man insistent on a director’s individual vision, since his own vision is so important to his own films. In other words, he’s no Selznick.

Without an established name to sell to American audiences, Bayona successfully took advantage of his producer’s stature, probably getting more attention to his ghost story than he would normally receive. But I can’t deny that Bayona’s themes—specifically that of a fantastical plot device existing in either reality or the protagonist’s mind (something the audience has to make a judgment on)—reflect Del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth in design. Nevertheless, Bayona’s picture generates enough shivers up the spine for an easy recommendation. In the wake of The Sixth Sense and The Others, spooky ghost stories are all too familiar in recent years. This one is directed with a careful hand and looming suspense. Bayona approaches his story with patience and dread, reminding us why suspense relies on what we don’t see, the possibility, as opposed to immediately pulling the curtain back on blood and gore.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review