The Life of Chuck

By Brian Eggert |

How should I approach writing about The Life of Chuck? I am tempted to use hyperbole, which would not at all be inappropriate. The phrase “life-affirming” gets thrown around a lot as a critical superlative, and those who employ it often do so with the hope of nabbing a place on promotional posters and trailers. For that reason, it’s a phrase I generally try to avoid, except on rare occasions. This is one of them. Once again adapting Stephen King, writer-director Mike Flanagan takes on the 58-page short story featured in the author’s 2020 collection, If It Bleeds. It’s a film with a curious narrative structure that poses existential questions about the meaning of life, leading to a metaphysical understanding wrapped up in mathematics and Walt Whitman’s poem “Song of Myself.” As one character explains in a resonant speech, there’s an art to how math can help us understand our place in the universe, from tracking the length of a stellar day to charting the tempos of music and heartbeats. But drawing from Whitman, there’s a more intuitive way to achieve understanding—a feeling that every individual is complex, unfathomable, and a prism for all humanity. In a manner both passionate and eloquent, Flanagan has made a profound, searching film that imparts a philosophy about who we are and how we’re all interconnected.

Flanagan has the rare ability to capture what is cinematic about King’s writing—something few filmmakers have done well. Frank Darabont (The Mist, 2007), Rob Reiner (Misery, 1990), and Brian De Palma (Carrie, 1976) belong on the shortlist alongside Flanagan. Contributions from Mick Garris (The Stand, 1994), Lawrence Kasdan (Dreamcatcher, 2003), and many others have been too literal about translating King to screen, resulting in clunky movies. Although King’s scenarios, prose, and horror sequences sometimes feel informed by cinema, his dialogue often sounds unnatural when spoken aloud, and his endings tend to underwhelm. King’s track record as a best-selling author means his work is among the most adapted (after Shakespeare), yet many of the movies based on his fiction end up forgettable or just plain bad. However, in Flanagan’s Gerald’s Game (2017) and Doctor Sleep (2019), the writer-director demonstrates that he knows when to adhere to the source material and when to revise a line or story choice for his medium. He also looks beyond the genre trappings of King’s work to see its humanity. And despite its horror-centric author, The Life of Chuck is not scary; it’s a cinematic poem about self-love and making connections.

Flanagan’s approach marries cinema and literature in that he finds a way to underscore the more cinematic aspects of King’s writing while also folding literary elements into his filmmaking. Take Nick Offerman’s familiar and welcoming voice as The Life of Chuck’s narrator. Most film critics and theorists favor the “show, don’t tell” method of storytelling, as cinema’s visual nature demands it more strictly than literature, which allows greater freedom for inner thoughts and exposition. Narration and internal monologues tell, and many deem them uncinematic. However, Flanagan goes against that ideal. Offerman’s narrator speaks the prose from King’s story, adding remarks about what characters think or will realize later in life. His voice explains some moments and punctuates others. He even occasionally interjects a “he said” between lines of onscreen dialogue, as though the film were a visualization of an audiobook. Everything I know about film criticism suggests that this technique should not work. But Flanagan’s clear-headed passion for King’s voice and confident direction of his actors render a fascinating hybrid of screen and text—less a straightforward film than a filmic fable shared by an omniscient storyteller.

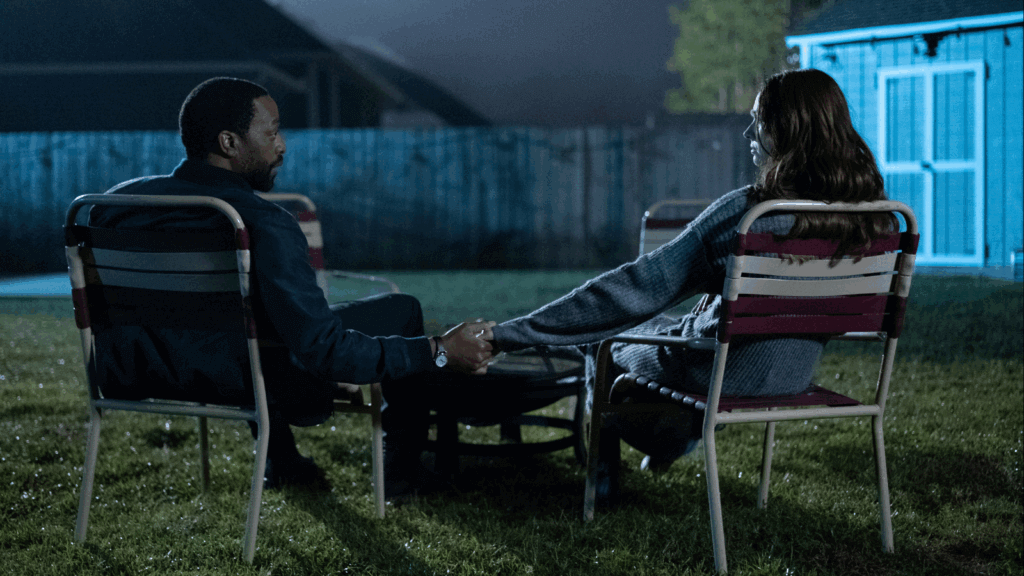

Indeed, The Life of Chuck is a rare film based on literary fiction that outshines its origins by playing to each medium’s strengths. Following the short story’s nonchronological structure in three acts, Flanagan begins with “Act Three” and works his way back through time to explore aspects of Chuck Krantz’s life. Who is Chuck Krantz? That is the question on the minds of everyone in the first segment, set in a world on the verge of collapse. Wildfires, volcanoes, tidal waves, floods, and sinkholes eat away at the planet. News broadcasts show the worst, but soon internet, television, and cell services go down. Facing The End, people respond with absenteeism and rampant suicides. Amid the chaos, once-married schoolteacher Marty Anderson (Chiwetel Ejiofor) and his ex-wife, nurse Felicia Gordon (Karen Gillan), gravitate back to each other in their final days. They join others who wonder about the billboards, commercials, and, later, supernatural projections thanking Chuck (Tom Hiddleston) for “39 great years.” Is he the “last meme” or the “Oz of the Apocalypse?” Who is this man no one seems to know, yet who feels omnipresent? And what does he have to do with the apocalypse?

In the second segment, we finally meet Chuck, who does not yet know he only has nine months left to live. Hiddleston embodies the thin accountant who, while away at a conference, happens upon Taylor (Taylor Gordon), a Juilliard dropout and busker. Her street drumming prompts Chuck to break into a spontaneous dance before convincing an onlooker, the freshly dumped Janice Halliday (Annalise Basso), to join him. While this scene occurs in the short story, music and dance come alive in cinema more than they can on the page. Music must be heard and felt to be understood, not read about; dance must be seen, and literature denies that. Cinema, as evidenced by Chuck’s childhood love of movie musicals such as Cover Girl (1944), enriches song and dance by capturing them in harmony, brought to life here through choreography by Mandy Moore and Gordon’s actual drumming. And so, the sequence where Chuck and Janice dance proves joyous beyond description, like watching Gene Kelly and Cyd Charisse in Singin’ in the Rain (1952) for the first time. I found my eyes welling up for no apparent reason other than I found what I saw beautiful in a way King’s writing could not capture.

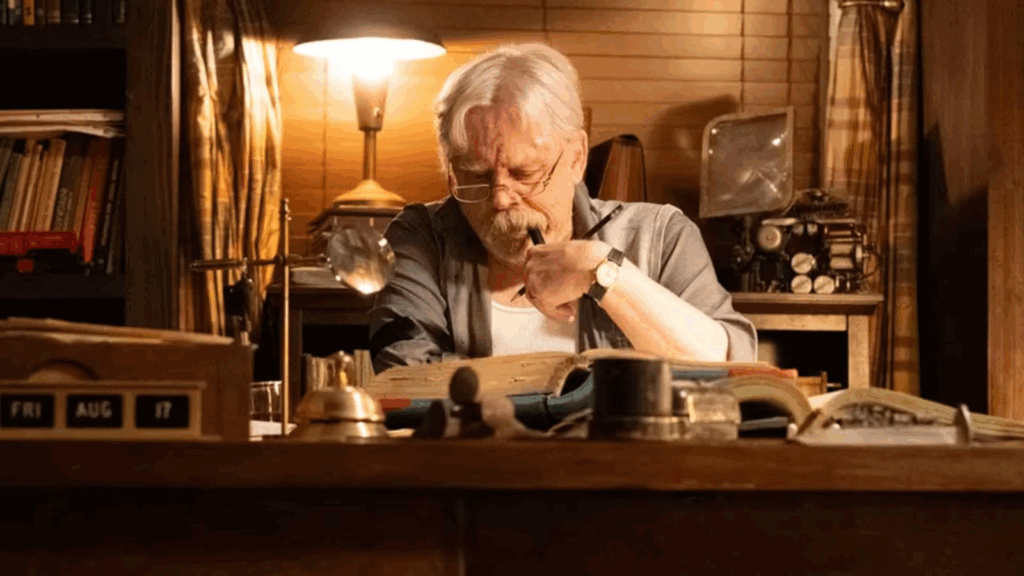

The final chapter is “Act One,” centered around the adolescent Chuck (Benjamin Pajak). After losing his parents in an accident, he lives with his grandparents: Albie (Mark Hamill), an accountant who wants Chuck to follow his path, and Bubbie (Mia Sara), a sprightly woman who passes her love of dancing and watching classic musicals on to Chuck. This final—or first—chapter is more complex, at once anticipating a school dance where Chuck and a girl from his “Twirlers and Spinners” team plan to show off their moves. But there’s also the mystery of why Albie forbids Chuck from exploring their house’s cupola. Is the wood floor really rotted up there, as Albie claims, or is it something else? “It’s full of ghosts,” Albie admits one night, while drunk. That doesn’t begin to explain it, though. Perhaps the most formative encounter from this time is Chuck’s brief exchange with his teacher (Kate Siegel), whom he asks about Whitman’s poem and the meaning of the film’s central idea: “I contain multitudes.” How Flanagan interweaves that concept through the film’s three acts and Chuck’s life, well, I’ll leave that for you to discover. Yet, even in young Chuck’s best moments, tears started to stream down my face, thinking about how this kid, too, would die, and his universe would end.

However unconventional the film’s structure, it’s held together partly by the power of Flanagan’s impressive cast. Besides those mentioned, many others, including Flanagan regulars, appear: Matthew Lillard, Carl Lumbly, Q’orianka Kilcher, Heather Langenkamp, Samantha Sloyan, David Dastmalchian, and Harvey Guillén. Most of them have minor roles, save for Pajak, who has the most substantive part. Hiddleston shines in the second act, appearing on signs and in flashforwards throughout. But his role is limited, even if its impact is incalculable. This is true of many performances in the film. Flanagan has a way of imbuing his players with moving dialogue or weighted scenes that turn minor roles into major ones. Consider how Ejiofor’s heartening presence and empathetic expression anchor the early scenes, despite limited screentime. Flanagan and his actors generate an intangible connection and humanity that defies their finite presence and radiates outward. Trying to put this into words, I was at a loss. After thinking about it, my wife came up with the phrase “supernatural intimacy,” and that sounds right.

Those familiar with Flanagan’s movies or limited series on Netflix (The Haunting of Hill House, Midnight Mass, et al.) will recognize his penchant for moving speeches and long, patient takes that showcase his actors. He’s a sentimental filmmaker, even melodramatic, but I do not use those terms pejoratively. On the technical side, Flanagan serves as editor, and his cutting is invisible, just as cinematographer Eben Bolter’s lensing doesn’t resort to conspicuous or flashy movements to convey an undue style. Flanagan’s formal signatures remain recessive, deployed to emphasize the story and characters first. Still, he designs unforgettable details, such as the haunting sound of stars disappearing from the sky or the chilling refrain of every heart monitor in an abandoned hospital beeping at the same 75-bpm tempo. His auteurist stamp can be characterized less by aesthetic flourishes than by his emotional and narrative clarity. For instance, Flanagan adds a detail that reframes the entire first act, which takes place in the final seconds of an individual’s life. He links this to Carl Sagan’s cosmic calendar—a visualization of how, if the Big Bang took place in the first seconds of January 1, human civilization would have only existed for the last 10 seconds of December 31. But that doesn’t make human life any less significant.

Flanagan’s adaptation complements, enriches, and fleshes out King’s short story, as though the filmmaker saw the potential in the author’s transcendental ideas and knew just how to expand on and articulate them with cinema. It’s an emotionally overwhelming experience, full of humanity, joy, and sadness, and anchored by a poetic understanding of life. How many movies give us a philosophy for how to live? How many movies impart any feeling whatsoever on our place in the universe? Here’s one that considers how existence might be explained by stellar mathematics, expressions of poetry and dance, or something altogether otherworldly. The Life of Chuck reminds us to embrace and savor every moment, because one of them will, eventually, be our last. Everyone dies—we know that, of course—but we don’t often live like we do. We should be living like every person we meet is another chance to expand our universe. The world is suffering from a vile strain of intolerance right now; people have shut themselves off from one another and stopped practicing empathy. The Life of Chuck is a tonic for despair.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review