Reader's Choice

Reviews commissioned and selected by Patrons

Misery

4 Stars- Director

- Rob Reiner

- Cast

- James Caan, Kathy Bates, Lauren Bacall, Richard Farnsworth, Frances Sternhagen, J.T. Walsh

- Rated

- R

- Runtime

- 107 min.

- Release Date

- 11/30/1990

Rob Reiner’s Misery is a distinctly cinematic adaptation of a Stephen King novel. Though not faithful in the strictest sense, as the author’s more literal devotees will note, the translation from the page to the screen enhances the story’s strengths in visual terms. Reiner has turned the claustrophobic spaces and prolonged suffering of King’s text into an anxious Hitchcockian thriller of compelling performances and dexterous filmmaking. Adapted by William Goldman, the Oscar-winning screenwriter of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and All the President’s Men (1976), the film diverts from the novel, adding new characters created for the screen and allowing the viewer to escape the narrow boundaries of the protagonist’s mind. But as fealty to the source material wavers, Misery replaces the omissions with alternate pleasures and horrors. Delightfully funny and sadistic, the film’s central performances by James Caan and especially Kathy Bates bring the material to vivid life, recalling the cramped spaces and descending goodwill of the conversation between Marion Crane and Norman Bates in Psycho (1960)—albeit extended for under two hours. As actor Michael O’Keefe once observed, it’s a film designed to scare white male authors who have persecutory delusions, but it plays on every viewer’s sense of claustrophobia and fear of the insane.

King’s novel finds the author waxing about the downfalls of celebrity and fervent readership. His 1987 best-seller, originally planned for his pseudonym, Richard Bachman, tells a personal tale that dramatizes his feelings of being trapped by success. King also seems to have drawn from the framing narrative of One Thousand and One Nights (known in English as Arabian Nights) to sinister effect. In that ancient text, the Persian king, enraged over his wife’s unfaithfulness, resolves to marry and kill a virgin every day in a cracked plan to ensure he’s never cuckolded again. After hundreds of women die by the king’s hand, along comes Scheherazade, a learned young woman versed in stories, history, and poetry. Scheherazade survives her first day with the king by telling him a story, extending it through the night and leaving him without an ending, thus preserving his interest until the following night. Using her gifts as a storyteller, she keeps the king in suspense, rapt in her stories for 1,001 nights, until the king falls in love and resolves to keep Scheherazade as his bride.

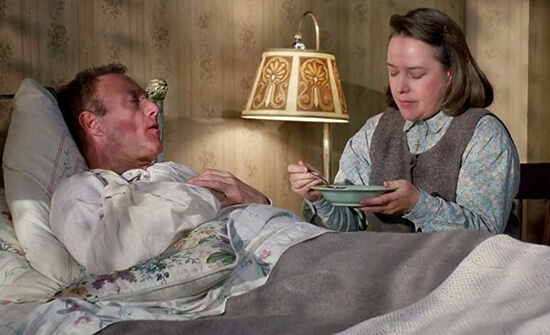

In the basic setup of Misery, author Paul Sheldon (Caan) crashes his car in the Colorado Rockies, only to be rescued by his psychotic “number one fan,” Annie Wilkes (Bates). Sheldon, known for writing a series of costume romances about the heroine Misery Chastain, books filled with English manners and sultry romance, has resolved to write something he’s passionate about: gritty slum kids. After completing work on his latest, more serious work of literature, Paul swerves off the icy road in a blizzard, where he’s saved by Annie, a nurse-cum-killer, who was following him. Paul awakes to find himself held prisoner in Annie’s isolated farmhouse in the mountains, where her cheery if idiosyncratic veneer gives way to terrible outbursts of anger and, eventually, violence. The first warning sign comes when she loses her grip over Paul’s use of swear words in his latest manuscript, followed by a confession of love. “Your mind, I mean,” she clarifies. Later, Annie’s very short fuse proves to be psychopathy after she completes Paul’s latest Misery novel, in which the beloved character dies, prompting Annie’s cooly acidic reaction: “You dirty bird.” From there, she goes full nutjob, announces her plan to keep Paul, and forces him to burn his latest book and resurrect Misery in a new novel. “I expect nothing less than your masterpiece,” she tells him. Writing to stay alive like Scheherazade, Paul desperately manages Annie’s temper while punching out a new book on a typewriter with a missing “N” key.

In the basic setup of Misery, author Paul Sheldon (Caan) crashes his car in the Colorado Rockies, only to be rescued by his psychotic “number one fan,” Annie Wilkes (Bates). Sheldon, known for writing a series of costume romances about the heroine Misery Chastain, books filled with English manners and sultry romance, has resolved to write something he’s passionate about: gritty slum kids. After completing work on his latest, more serious work of literature, Paul swerves off the icy road in a blizzard, where he’s saved by Annie, a nurse-cum-killer, who was following him. Paul awakes to find himself held prisoner in Annie’s isolated farmhouse in the mountains, where her cheery if idiosyncratic veneer gives way to terrible outbursts of anger and, eventually, violence. The first warning sign comes when she loses her grip over Paul’s use of swear words in his latest manuscript, followed by a confession of love. “Your mind, I mean,” she clarifies. Later, Annie’s very short fuse proves to be psychopathy after she completes Paul’s latest Misery novel, in which the beloved character dies, prompting Annie’s cooly acidic reaction: “You dirty bird.” From there, she goes full nutjob, announces her plan to keep Paul, and forces him to burn his latest book and resurrect Misery in a new novel. “I expect nothing less than your masterpiece,” she tells him. Writing to stay alive like Scheherazade, Paul desperately manages Annie’s temper while punching out a new book on a typewriter with a missing “N” key.

Of course, Bates, a theatrically trained performer in her first major role in a motion picture, won the Oscar for Best Actress and forever associated herself with the horror genre (see her dependable presence on FX’s American Horror Story). Her version of Annie Wilkes, far different from the character in the book and less an embodiment of King’s disgust with his own fanbase, has an almost quaint, pathetic quality about her. In a series of details that originated with Goldman, Annie likes Liberace records, watches Love Connection, and serves her meatloaf with a hint of SPAM. She’s far more banal and less crazy than the paranoiac of King’s book, who used her own hair to indicate whether a drawer has been opened when she’s away. Rather, Bates fulfills the notion of an obsessed fan, one who adopts an old-fashioned way of speaking in serious situations: “There is something you must do,” she tells Paul in an affected tone, before forcing him to burn his latest manuscript. The film’s Annie, besides living alone and having a chequered past of infanticide, also talks to God. She wears a cross on her neck and admits that “God told me” on more than one occasion, but her hypocritical devotion doesn’t prevent her from kidnapping and maiming Paul. Reiner and Goldman’s portrait of an overweight, SPAM-eating, tasteless, and short-tempered religious nut certainly takes aim at a specific type, while also underscoring the author’s self-depreciation if someone like Annie Wilkes is the standard representation of his fanbase.

King had resisted selling the film rights to Misery due to its personal nature, although Reiner had thoroughly impressed the author when he adapted another intimate story, “The Body,” into the superb Stand by Me from 1986. The All in the Family star could relate to Paul Sheldon, feeling trapped by his success in sitcoms and as the son of Carl Reiner. Perhaps this shared motivation convinced King that Reiner would make a worthy version of his book. King sold the film rights for his standard one-dollar asking price, and Reiner launched the project at his production company, Castle Rock Entertainment, named after the town in Stand by Me. Castle Rock would develop several other King novels, including Needful Things (1993), The Shawshank Redemption (1994), Dolores Claiborne (1996), The Green Mile (1993), Hearts in Atlantis (2001), and Dreamcatcher (2003). To adapt the novel, Reiner returned to Goldman, whose novel The Princess Bride the director had turned into the beloved 1987 comedy-fantasy. Goldman translated King’s text from the literary to the cinematic, cutting the long chapters from the book that concern themselves with the writing process. He also excises much of the more extreme horror and incorporates elements of humor, allowing the viewer out of the confines of Paul Sheldon’s headspace (an admittedly unpleasant place).

Although Misery could be faulted for breaking the austere, confined two-hander structure of King’s book, Goldman’s inclusions prove rather enjoyable. Several scenes occur outside of the Wilkes’ farmhouse, the sole location of the book. The viewer sees Paul complete the last pages of his book and crash on the icy mountain road; we meet his New York editor, played by Lauren Bacall; and best of all, Goldman includes the wily old sheriff, Buster (Richard Farnsworth), and his wife Virginia (Frances Sternhagen), a cute old couple that ostensibly run the nearest town. Much of the film’s runtime builds tension as Buster, ever bickering lightheartedly with his wife, comes closer to discovering Paul’s whereabouts. Farnsworth, occupying a familiar Dick Hallorann trajectory, charms as a cop who never lets on, avoids assuming the worst (at least audibly, though it’s clear he suspects Wilkes), and has a particular way of doing things. When Paul’s agent first reports him missing, Buster promises to “put it through our system”—a post-it reminder amid an organized mess of paperwork. Inevitably, Buster meets a predictable demise, but mercifully, it’s a far less gory fate than the one visited upon the cop in King’s book. Regardless, the scenes with Buster and Virginia free the audience from the claustrophobic insanity of Paul’s captivity with comic relief and exposition that would otherwise occur in the protagonist’s head, which may diminish the terror of King’s story. Instead, they transition the story of Misery into the playful pleasure of Hitchcockian filmmaking.

Although Misery could be faulted for breaking the austere, confined two-hander structure of King’s book, Goldman’s inclusions prove rather enjoyable. Several scenes occur outside of the Wilkes’ farmhouse, the sole location of the book. The viewer sees Paul complete the last pages of his book and crash on the icy mountain road; we meet his New York editor, played by Lauren Bacall; and best of all, Goldman includes the wily old sheriff, Buster (Richard Farnsworth), and his wife Virginia (Frances Sternhagen), a cute old couple that ostensibly run the nearest town. Much of the film’s runtime builds tension as Buster, ever bickering lightheartedly with his wife, comes closer to discovering Paul’s whereabouts. Farnsworth, occupying a familiar Dick Hallorann trajectory, charms as a cop who never lets on, avoids assuming the worst (at least audibly, though it’s clear he suspects Wilkes), and has a particular way of doing things. When Paul’s agent first reports him missing, Buster promises to “put it through our system”—a post-it reminder amid an organized mess of paperwork. Inevitably, Buster meets a predictable demise, but mercifully, it’s a far less gory fate than the one visited upon the cop in King’s book. Regardless, the scenes with Buster and Virginia free the audience from the claustrophobic insanity of Paul’s captivity with comic relief and exposition that would otherwise occur in the protagonist’s head, which may diminish the terror of King’s story. Instead, they transition the story of Misery into the playful pleasure of Hitchcockian filmmaking.

Indeed, Reiner has noted in interviews that he revisited the films of Alfred Hitchcock before shooting Misery, and the Master of Suspense’s influence can be felt throughout. Reiner incorporates Hitchcock’s penchant for simple, gestural inserts that place focus on objects and hands. Shots of Paul’s hands lighting a cigarette or flipping on the windshield wipers may seem oddly specific, but the extreme close-ups of Paul’s fingers as he wiggles a hairpin in a keyhole to escape makes the moment ever more desperate. Reiner’s cinematographer, Barry Sonnenfeld, who graduated to director himself after Misery, makes excellent use of the story’s cramped spaces. The camera often isolates Paul in the frame—sometimes from a God’s-eye-view—to emphasize his hopelessly trapped and alone status. But in moments of heightened tension and violence, particularly involving Annie’s rants, Sonnenfeld employs wide-angle lenses to capture her off-kilter quality. Thanks to the lenses, Bates’ eyes almost seem to diverge in opposite directions as she shouts about the unfair narrative games of “cocka-doodie” chapter plays. For a film that takes place in a limited number of locations, Misery is sharply cinematic.

Perhaps for the best, Goldman has toned down some of Paul Sheldon’s unsavory characteristics from the book, which may not have translated well into a crowd-pleasing thriller. King wrote Paul as an addict who relies on Annie’s regular delivery of opioids and spends much of his time in her care in a drug-addled haze. Similarly, Annie was far nastier in the book, literally hacking away at Paul by removing his feet with an ax and cauterizing the wound with a blowtorch, and then later lighting his dismembered finger on fire as a makeshift candle on a birthday cake. Horrible as that may sound, the reality of “hobbling” Paul’s swollen, purple feet with a sledgehammer, despite its lack of blood and blowtorch, is far worse. Or maybe it just seems that way with how Reiner filmed it. The iconic moment of horror cinema is heightened by Caan’s performance; he writhes and sweats, screaming bloody murder in such a way that cannot help but produce phantom pains in the viewer’s legs and feet. Moreover, it’s curious that one of the most excruciating moments of Misery is when Paul pulls himself onto the floor, and those crippled legs fall with all their dead weight, leaving our hero in a near-catatonic state of unimaginable pain. We can feel the moment, and it hurts.

Goldman also toned-down some of the more blatant misogynistic flourishes of King’s book, but not all of them. Fortunately, the viewer of Misery is spared the traumatized, half-insane Paul as he acts out orally raping Annie with burning remains of the book that she forced him to write. Caan’s version of the character remains fairly grounded, represented through moments of utter exhaustion and shit-eating expressions that gratify and calm his warden. Still, this is a film told from the male perspective, whereas the resident female, Annie, has been portrayed as an unhinged and unkempt weirdo who keeps a pig (Misery the sow is adorable), loves gameshows, eats Cheetos in bed, and savors trashy literature. She’s also a racist. “What’s the name of that ceiling that dego painted?” she asks Paul, referring to Michelangelo’s work on the Sistine Chapel. Paul, meanwhile, must endure her unwanted affections (“God, I love you,” she exclaims after crushing his feet with a sledgehammer), until he can beat her to death before his crawl to freedom. It’s a moment of reclamation for both Paul, the story’s male Scheherazade, and Stephen King, who pushes away the obsessive female fan—thus avoiding the murder-suicide she had planned for them upon the book’s completion.

Goldman also toned-down some of the more blatant misogynistic flourishes of King’s book, but not all of them. Fortunately, the viewer of Misery is spared the traumatized, half-insane Paul as he acts out orally raping Annie with burning remains of the book that she forced him to write. Caan’s version of the character remains fairly grounded, represented through moments of utter exhaustion and shit-eating expressions that gratify and calm his warden. Still, this is a film told from the male perspective, whereas the resident female, Annie, has been portrayed as an unhinged and unkempt weirdo who keeps a pig (Misery the sow is adorable), loves gameshows, eats Cheetos in bed, and savors trashy literature. She’s also a racist. “What’s the name of that ceiling that dego painted?” she asks Paul, referring to Michelangelo’s work on the Sistine Chapel. Paul, meanwhile, must endure her unwanted affections (“God, I love you,” she exclaims after crushing his feet with a sledgehammer), until he can beat her to death before his crawl to freedom. It’s a moment of reclamation for both Paul, the story’s male Scheherazade, and Stephen King, who pushes away the obsessive female fan—thus avoiding the murder-suicide she had planned for them upon the book’s completion.

Whether or not Goldman intended a subtext about gendered power in Misery, much of the complex psychological characterization in King’s book has been muted. Reiner’s ambitions to make a Hitchcockian thriller prevail and, on those terms, the film performs splendidly, ratcheting the suspense in scene after scene. If King’s novel was preoccupied with the writer’s experience and headspace, then the film demonstrates a filmmaker exploring the language of a thriller, employing its tricks and devices to superb effect. It’s a film that shows how the root of a King story can remain, even if a filmmaker has different sensibilities. After his heyday of the 1980s, a period ranging from the mockumentary This Is Spinal Tap (1984) to A Few Good Men (1992), the bottom dropped out on Reiner’s career with the 1994 flop North. Reiner stopped experimenting with genres and resigned himself to easygoing romantic comedies that failed to retain a place in the viewer’s memory. Misery represents one of the last times Reiner tested himself, and it’s a resounding example of what an elegant tactician he could be behind the camera.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon by Brenda. Thank you for your support!)

Baghead

Baghead  A Horrible Way to Die

A Horrible Way to Die  Hereditary

Hereditary