The Eternal Daughter

By Brian Eggert |

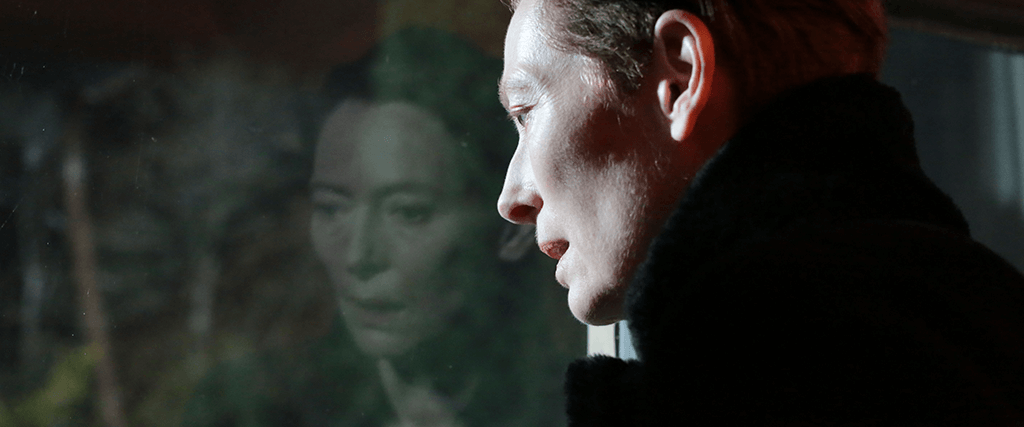

In Joanna Hogg’s The Eternal Daughter, the viewer sees Julie, played by Tilda Swinton, reading “They,” a short story by Rudyard Kipling from 1904, just before bedtime. The story features a bereaved father driving through Sussex. He finds himself at an ornate house, where he sees children playing and then feels haunted by the memory of his late daughter. After returning to the mysterious place three times, he realizes the children are ghosts; more importantly, he finally accepts that his grief over his dead child will forever remain a part of him. It’s a telling story for Hogg’s film, which follows Julie, a filmmaker who travels with her mother, Rosalind, to a hotel with a haunted history worthy of a Victorian ghost story. When Kipling wrote “They,” he had lost his daughter Josephine a few years earlier and worked through his pain using autofiction. Similarly, Hogg, whose mother died while The Eternal Daughter was in post-production, doubtlessly uncovered a feeling of closure about her mother through the filmmaking process. As a result, the film’s themes about loss and memory, and how artists mine them, resonate throughout this unearthly yet tender film.

Hogg has already made two features based on her life, and The Eternal Daughter continues that thread, except with a touch of gothic atmosphere. The filmmaker’s superb The Souvenir (2019) and its even better sequel from 2021 featured Swinton as Rosalind, and her real-life daughter Honor Swinton Byrne played Julie Hart, a stand-in for the writer-director. Those films took place in the 1980s and dramatized Hogg’s growth from a naive film student to a burgeoning filmmaker. Her latest, which could be the third in a trilogy, takes place in a modern setting and, in a bravado flourish (which doubtlessly made the COVID-era production easier), Swinton plays both mother and daughter roles. The primary location is a Welsh hotel, which used to be owned by Rosalind’s aunt. Julie brings her elderly mother there for a birthday weekend, hoping the familiar scenery will conjure happy memories. But inside the hotel, Julie experiences things that go bump in the night, while outside, the moaning winds, dark woods, and lingering fog make for spooky surroundings.

Given Hogg’s filmography, any material dabbling in the supernatural represents a considerable departure, but The Eternal Daughter never gives itself over to the genre. Instead, it feels as though Hogg wields the familiar signifiers of a haunted house story to explore deeper questions about losing someone dear and how to grapple with memories of them—as with Kipling and his short story. Still, from the first images that deliver Julie and Rosalind to the hotel, set against unnerving music—the same composition by Hungarian composer Béla Bartók heard in The Shining (1980)—Hogg establishes an eerie if sometimes comical atmosphere. Checking in, Julie faces a room mix-up with the hilariously curt and unaccommodating desk clerk (Carly-Sophia Davies), who doesn’t have the welcoming spirit you might expect at a hotel. Though, stranger still, they seem to be the hotel’s only guests. Eventually, they get settled into their shared room, but Julie cannot sleep, not with so many noises filling the night. And outside of their room, the hotel offers poorly lit hallways, unexplained shadows, grotesque statues on the roof, persistent storms, and an ominous moon.

Much of The Eternal Daughter seems straightforward from a plotting perspective, and the start is relatively slow. Although the surface may suggest that nothing much happens, the overall effect is engrossing upon reflection. Over the next few days, Julie attempts to preserve her memories of her mother, who may not be around much longer, by covertly recording their conversations during dinner or before bed. She also attempts to start a new script (which, presumably, turns out to be the film we’re watching). For the time being, however, Julie has writer’s block, compelled by the uncanny hotel and concern for her mother. At the same time, Rosalind finds Julie’s behavior to be that of a “fusspot.” Julie is perhaps overly worried that, along with her mother’s fond recollections of the hotel, there are some unpleasant reminders of the past—she wanted their getaway to be a happy one. But Julie ignores the inescapable: every structure holds its share of positive and negative memories. This is echoed by the resident caretaker, Bill (Joseph Mydel), who tells Julie that he worked at the hotel with his late wife for 30 years before her death. He stays to remain close to her memory.

Much of The Eternal Daughter seems straightforward from a plotting perspective, and the start is relatively slow. Although the surface may suggest that nothing much happens, the overall effect is engrossing upon reflection. Over the next few days, Julie attempts to preserve her memories of her mother, who may not be around much longer, by covertly recording their conversations during dinner or before bed. She also attempts to start a new script (which, presumably, turns out to be the film we’re watching). For the time being, however, Julie has writer’s block, compelled by the uncanny hotel and concern for her mother. At the same time, Rosalind finds Julie’s behavior to be that of a “fusspot.” Julie is perhaps overly worried that, along with her mother’s fond recollections of the hotel, there are some unpleasant reminders of the past—she wanted their getaway to be a happy one. But Julie ignores the inescapable: every structure holds its share of positive and negative memories. This is echoed by the resident caretaker, Bill (Joseph Mydel), who tells Julie that he worked at the hotel with his late wife for 30 years before her death. He stays to remain close to her memory.

Elsewhere, as a pleasant detail in most scenes, Swinton’s real-life springer spaniel named Louis plays Rosalind’s dog, offering one of the most genial (and most distracting, in the best way possible) canine performances in recent memory. He rolls onto his back, rests his head on Rosalind’s arm, and cuddles at night. Dog lovers will notice Louis’ apparent level of comfort with Swinton in both roles, which suggests a natural bond between them. There’s never a hint of a trainer off-screen with a clicker and pouch of treats. Louis loves Swinton, and it’s obvious he’s a good boy. But, of course, it would be unfair to judge any dog’s performance too harshly. Often, a memorable dog performance is made somewhere between the animal wrangler and the film editor. But it’s a pleasure to see their mutual affection onscreen here. It’s only unfortunate that The Eternal Daughter didn’t debut until this year’s Venice Film Festival in September, as Louis surely would have earned the Cannes Film Festival’s coveted Palm Dog award—whose past recipients include Lucy from Kelly Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy (2008) and Brandy from Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019).

In any case, Hogg’s direction of The Eternal Daughter makes the dual performances by Swinton seem less like a casting stunt and more like another peculiar component of a paranormal experience. At times, one might forget that Swinton is playing both roles, except for the shot/reverse shot editing of Julie and Rosalind’s scenes together. Hogg probably didn’t have the budget to put the characters in the same shots using CGI, and achieving the effect practically would have turned the filmmaking process into a time-consuming and costly technical enterprise. Rather, they appear together for one crucial scene, and the devastating shot that follows emphasizes the significance of that moment. In other visual flourishes, cinematographer Ed Rutherford shoots on 35mm; he evokes the textured work of Guillermo del Toro in Crimson Peak (2015) and even approaches the primary-hued visuals in Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977). Green and blue splashes of light permeate hallways and accent walls, giving the impression that the hotel might disappear into mist when Julie leaves.

Ultimately, Hogg’s ghosts, uncanny imagery, and supernatural locale do not intend to frighten the viewer or give us nightmares. Rather, The Eternal Daughter considers how people preserve those who are gone. In Hogg’s (and thus Julie’s) case, the film explores how children grapple with the loss of their parents. Will they be remembered selectively or become the inspiration for a creative project? It also explores how memory can be a choice, shaped by how we choose to remember the people and events in our lives. When Rosalind mourns at one point that Julie never had children, she resolves that Julie’s children are her films, and it points to Julie’s chosen method of memory. If Julie cannot pass down her memories to a literal child, she can include her memories in her films, which will live on forever. The film and its title, then, become metaphors for memories preserved through artistic expression. By the end, The Eternal Daughter transforms into a heartrending affirmation of Hogg’s voice and purpose as an artist, as well as an unexpected yet impassioned statement on the vitality of personal filmmaking.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review