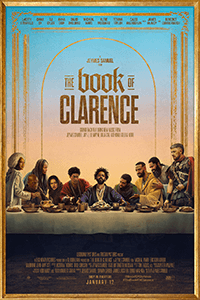

The Book of Clarence

By Brian Eggert |

In 2021, when everyone was preoccupied with the pandemic, Jeymes Samuel burst onto the scene in all his multihyphenate glory with The Harder They Fall, a revisionist Western boasting a stacked all-Black cast and a postmodern aesthetic. The musician-turned-filmmaker returns with his second ambitious feature, The Book of Clarence, another patchwork of influences that, in any given scene, might channel the cinema of William Wyler, Stanley Kubrick, or Monty Python. Blending skillful referentiality and bold storytelling, Samuel once again proves that he’s an inspired visual director who playfully dabbles in various styles and tones, depending on what the moment requires. But what begins as an almost farcical look at religion, reminiscent of Life of Brian (1979), quickly trails off into a dour and grandiose religious sermon. The film operates like a particularly inspired Sunday school lesson, which, the hilarity and irreverence of the lesson’s presentation aside, still feels like it’s robbing my Sunday of something better.

The general conceit is enough to conjure a laugh. LaKeith Stanfield plays Clarence, a drug-dealing opportunist in Jerusalem who wants to become Jesus’ 13th apostle, but his reasons are selfish. Owing money to a local bookie, Jedediah the Terrible (Eric Kofi-Abrefa), which he borrowed in hopes of wooing Jedediah’s sister (Anna Diop), Clarence thinks becoming an apostle will solve his problems. But his identical twin brother, the apostle Thomas (also Stanfield), will not welcome Clarence into the fold, knowing he’s faithless and just looking to save his skin. Clarence refuses to believe in Jesus; he wants knowledge, not faith. With the help of his best friend Elijah (RJ Cyler) and a freed gladiator, Barabbas (Omar Sy), Clarence sets out to dupe people into believing his “tricks” or false miracles, which allow him to collect donations and raise enough money to pay his debt. Initially, Clarence’s skepticism and “disrespectful” attitude toward religion is reinforced by how easily he’s able to convince crowds of people that he’s a new messiah.

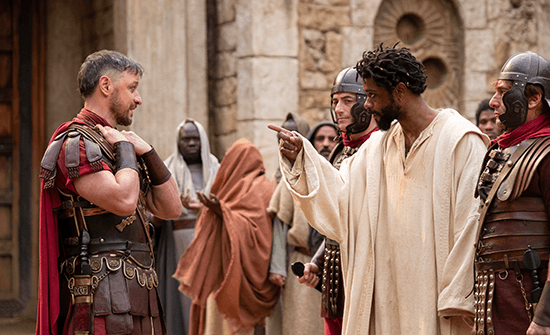

The Book of Clarence is throwing phantom punches at religion, however. Soon enough, Clarence’s conscience gets the better of him. “Who am I? What have I become?” he asks with the subtlety of a hammer. So he begins to use his influence to help the enslaved and downtrodden—though, he’s conspicuously inattentive to a local vagabond (Benedict Cumberbatch) covered in years of filth. Clarence’s false prophet routine gains the attention of the Romans, and Samuel’s clever script frames the centurions as a historical equivalent of predominantly white police forces that profile and target people of color—here, any Black men claiming to be the messiah, including Jesus (Nicholas Pinnock) and his apostles. Similar to The Harder They Fall, Samuel’s mostly Black cast addresses how the biblical epic genre in cinema, like so many others, has been inhabited by mainly white actors despite the historical inaccuracies of that choice.

Divided into three books, each marked by golden chapter cards modeled after classical epics of yesteryear—everything from The Ten Commandments (1956) to Ben Hur (1959)—The Book of Clarence includes a modern spin on those stately 1950s productions. Punchy editing courtesy of Tom Eagles and playful camera movements from d.p. Rob Hardy give life to the film’s more colorful sequences, some evoking familiar imagery such as Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper. The biggest laugh might come from Cumberbatch, who, when eventually scrubbed and shining, resembles the Christ icon and receives credit for everything the Black, real Jesus has done. Another scene finds Clarence and Elijah smoking pot, causing them to float until a literal lightbulb glows above our hero’s head, denoting his eureka moment. Elsewhere, the treatment is straightforward and rousing, evidenced in Barabbas’ subplot. A venerable warrior, Barabbas calls himself “immortal,” a claim that proves true during an altercation with racist authorities that inspired cheering in my screening.

Divided into three books, each marked by golden chapter cards modeled after classical epics of yesteryear—everything from The Ten Commandments (1956) to Ben Hur (1959)—The Book of Clarence includes a modern spin on those stately 1950s productions. Punchy editing courtesy of Tom Eagles and playful camera movements from d.p. Rob Hardy give life to the film’s more colorful sequences, some evoking familiar imagery such as Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper. The biggest laugh might come from Cumberbatch, who, when eventually scrubbed and shining, resembles the Christ icon and receives credit for everything the Black, real Jesus has done. Another scene finds Clarence and Elijah smoking pot, causing them to float until a literal lightbulb glows above our hero’s head, denoting his eureka moment. Elsewhere, the treatment is straightforward and rousing, evidenced in Barabbas’ subplot. A venerable warrior, Barabbas calls himself “immortal,” a claim that proves true during an altercation with racist authorities that inspired cheering in my screening.

Much like The Harder They Fall, Samuel has amassed an impressive cast of actors, adding an element of starstruck pleasure to the viewing. However, several roles are limited to a scene or two: Teyana Taylor makes a fierce, chariot-riding Mary Magdalene and later appears for a biblical stoning scene; Alfre Woodard plays Mother Mary, who shines in a bit where Clarence pokes holes in her immaculate conception story; David Oyelowo makes an appearance as a no-bullshit John the Baptist; and James McAvoy is an intimidating Pontius Pilate. Shot in Matera, Italy, the backdrop is another character, and a convincing one at that. Never for a moment does the production rely on sweeping digital effects shots that look phony. Samuel and production designer Peter Walpole create a convincing Jerusalem in A.D. 33, with stone buildings and dirt roads that often channel Hollywood production values of spare-no-expense 1950s epics. The whole movie is accented with Samuel’s score and a killer soundtrack.

Early in the movie, in a sequence inspired by Spartacus (1960), Clarence attempts to prove he’s worthy of becoming an apostle by freeing gladiatorial slaves. When Clarence arrives at the arena, the slave owner asks him, “Who are you, and how do you expect me to react to the news you are about to give?” It’s a difficult question to answer for The Book of Clarence, which never quite achieves a harmony between its satire, commentary on race, and narrative, which eventually turns into an unironic, sobering lesson in faith. But it’s easy to admire how Samuel tries something bold and unusual, employing random and delightful dance choreography for one sequence, a harrowing climb up Golgotha for another. But rather than prompt the audience to question and think critically about their beliefs, as Clarence does, the film ultimately treats faith and knowledge as equals, which feels like a slippery slope to radicalism. But these are the concerns of the unconverted, and Samuel is obviously speaking to religious viewers who will enjoy his riff on biblical material.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review