Sidney

By Brian Eggert |

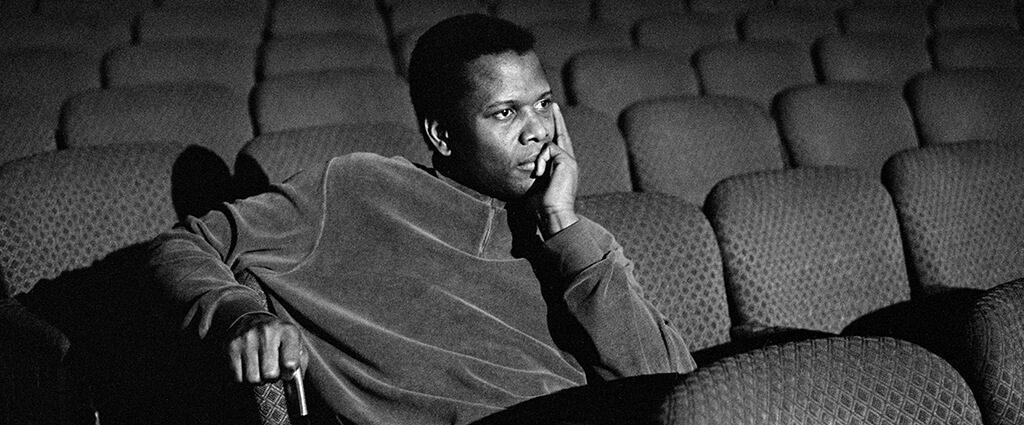

Documentaries about movie stars seldom offer in-depth surveys of their subjects. After all, how can a movie of average length hope to touch on every aspect of a celebrity’s life and legacy? So, through interviews and archival footage, docs of this kind give audiences a Wikipedia page summary, touching on the highlights and conveniently omitting some of the lower points. In most cases, the filmmakers are longtime fans or even family members who want to honor and memorialize the star. Titles from Love, Gilda (2018) to last year’s Val exist to remind audiences what they love about these performers, provide an overview of their work, and add some biographical context. If the doc is good, it might make us appreciate the actor even more and possibly convince us to read a biography or two. They’re not intended for superfans who already know the subject’s life and career back and forth; they’re intended for those who have always liked the star but don’t know much beyond what they’ve seen onscreen. With that in mind, Sidney, which tells the story of Sidney Poitier, does just what’s intended.

Poitier died earlier this year in January. Before his death, director Reginal Hudlin and producer Oprah Winfrey tapped the actor to appear in this documentary. The result largely succeeds because Poitier engages the audience by telling his story directly to the camera. If you’ve seen any of Poitier’s film appearances, you know he’s incredibly charismatic, with a vocal rigor and statuesque physicality that command the screen. Hudlin presents Poitier with crisp images, as if the audience were talking to him face-to-face, allowing his movie star glow to hypnotize us. When Hudlin captures other interview subjects—including Winfrey, Morgan Freeman, Quincy Jones, Spike Lee, Lou Gosset Jr., and many of Poitier’s children—the camera comes at them from an indirect angle, off to the side or, in the case of Denzel Washington, from a slightly lower angle to make him seem larger than life. Had Poitier not appeared, Sidney might not have had the same impact. What’s more, it might not have had the same degree of Poitier’s self-mythologizing about his breakthrough career, activism, and expansive family.

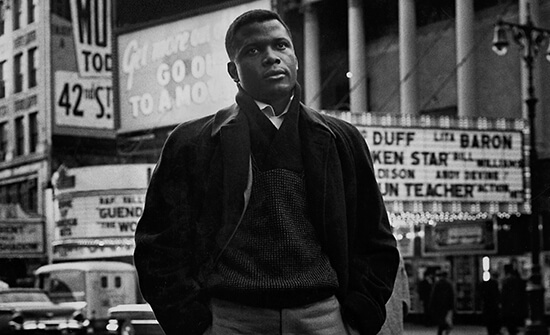

From the outset, Poitier paints a picture of his youth. It’s a story he’s been telling since his rise in the 1960s, evidenced by Hudlin’s use of archival footage of Poitier interviewed on The Dick Cavett Show and elsewhere. He grew up poor in the Bahamas to tomato farmers. With no concept of electricity, running water, or even mirrors at a young age, Poitier shares stories about traveling to Nassau and seeing a car for the first time. Then Winfrey chimes in, as she tends to do throughout Sidney, and explains how his upbringing in a predominantly Black community didn’t prepare him for the racism that he would face when he moved to Florida. Haunting stories about encounters with the Klu Klux Klan or a police officer who threatened to shoot him in the face underscore the culture shock. But these incidents only reinforced Poitier’s worldview that he should endeavor to become a better human being—not merely a Black man trying to make a career in a racist country, but a person like any other person, trying to do good.

And so, when Poitier made his way to Harlem and resolved to become an actor in the American Negro Theatre and eventually the movies, he made decisions that no other person of color in show business had ever made. Poitier turned down the stereotypical parts Hollywood had for Black actors at the time and pursued roles such as a doctor in his screen debut, No Way Out (1950), or the many stage-to-screen adaptations that helped propel his stardom. Each role had to meet specific criteria, both elevating himself and paying homage to his parents, specifically his father. Sidney notes that throughout the 1960s, Poitier became a box-office draw and Oscar winner, appearing in classics ranging from A Raisin in the Sun (1961) to three hits in 1967 alone: To Sir, with Love; In the Heat of the Night; and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. Cultural critic Nelson George offers some mild criticism of The Defiant Ones (1958), noting how Poitier’s role marked the first time many viewers had seen a Black man stand up to a white character, but it also contains a “Magical Negro” trope. Regardless, the fact that Poitier was a major star meant something to America’s identity.

And so, when Poitier made his way to Harlem and resolved to become an actor in the American Negro Theatre and eventually the movies, he made decisions that no other person of color in show business had ever made. Poitier turned down the stereotypical parts Hollywood had for Black actors at the time and pursued roles such as a doctor in his screen debut, No Way Out (1950), or the many stage-to-screen adaptations that helped propel his stardom. Each role had to meet specific criteria, both elevating himself and paying homage to his parents, specifically his father. Sidney notes that throughout the 1960s, Poitier became a box-office draw and Oscar winner, appearing in classics ranging from A Raisin in the Sun (1961) to three hits in 1967 alone: To Sir, with Love; In the Heat of the Night; and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. Cultural critic Nelson George offers some mild criticism of The Defiant Ones (1958), noting how Poitier’s role marked the first time many viewers had seen a Black man stand up to a white character, but it also contains a “Magical Negro” trope. Regardless, the fact that Poitier was a major star meant something to America’s identity.

Still, any real question of Poitier’s choices at the time feels negligible when Winfrey calls him the “Great Black Hope” and weeps over her love for him in typically hyperbolic moments. Aspects of Poitier’s sometimes volatile personal life, along with his hasn’t-aged-well choice to direct several comedies starring Bill Cosby, go mostly unconsidered. But of course, they wouldn’t be, not when the point of Sidney is to venerate The Man, The Myth, The Legend—a persona Poitier has worked very hard to craft. Perhaps years from now, someone will make a more unbiased documentary about Poitier, the point of which wouldn’t be to diminish his legacy but to offer a fuller portrait. People are complicated, and celebrities’ lives are no exception. Although it’s easy to watch the archival footage, interviews, and home videos on display in Hudlin’s film with a satisfying appreciation for Poitier the icon, the doc reinforces fandom more than it presents a complete picture.

While it would be easy to dismiss the doc for being so unabashedly exultant about Poitier’s impact, it’s impossible not to get swept up in its admiration. His role in the Civil Rights movement and his presence in Hollywood motion pictures helped reframe people of color to a white audience and inspire African-American viewers to follow his example. If his personal life was sometimes rocky and his career choices occasionally questionable, the net gain is undeniable. Above all, Hudlin’s film gives viewers their last chance to hear Poitier speak about his life. Perhaps the most powerful moments involve Poitier talking about his friendship with longtime friend (and competitor) Harry Belafonte; their collaboration on Poitier’s directorial debut, Buck and the Preacher (1972); and their terrifying encounter with the KKK in Mississippi. However closely Sidney follows the biographical doc template of talking heads and archival material, the topic remains fascinating and, like a good documentary about a movie star should, it makes the viewer want to explore his body of work further.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review