Showing Up

By Brian Eggert |

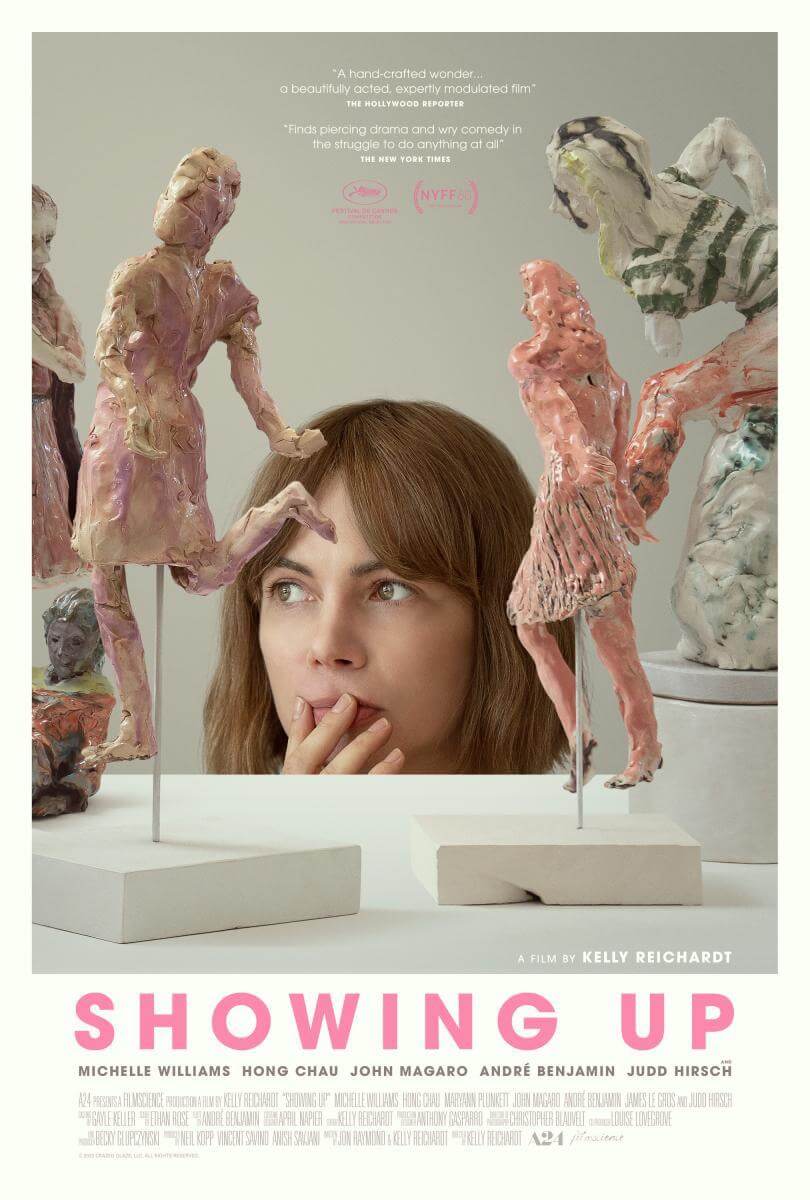

Kelly Reichardt’s Showing Up begins with a pigeon’s-eye-view of watercolor figure paintings affixed to a wall in a garage studio. Over the opening credits, the pigeon scans the artwork, quietly cooing in appreciation. This is where Lizzy Carr, played by Michelle Williams, creates her sculptures. The watercolors appear to be concept designs for her small, clay statues of women. Molded with her hands, Lizzy’s figures look crude and unfinished in their initial gray format. They stand just over a foot high, mounted on a metal rod with a base. The Portland-based artist shapes her clay into a rough form with her hands, attaches appendages, scratches textures for their clothes, and applies glaze. Each sculpture strikes an expressive pose; they dance, lean, run, and raise their arms. Even though her women take active stances, they appear afflicted. So does Lizzy, whose scowl is perpetual, revealing the effort in her creative process. Before long, and under rather dire circumstances, the pigeon finds itself drawn into Lizzy’s life, giving way to a portrait of an artist fraught with minor inconveniences, nagging obligations, and unromanticized creative work. Lizzy’s art is part drive and part obsession; it compels her and gives her meaning beyond everyday life. Of course, it’s also a reflection of her.

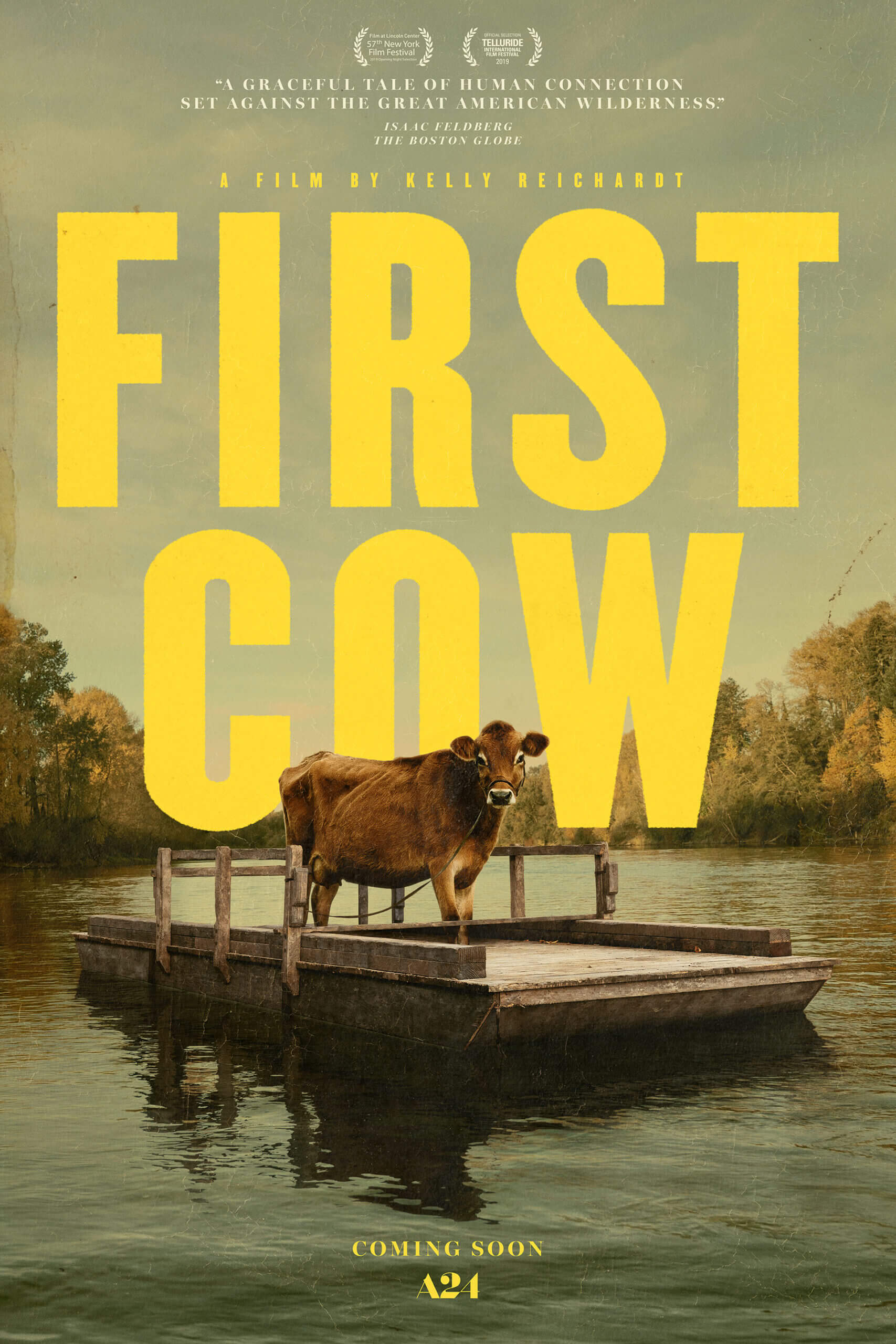

In the early stages of prepping Showing Up, Reichardt and her frequent screenwriting partner Jonathan Raymond wanted to make a portrait of an unknown artist—a film about balancing art and the practical concerns of life. Raymond wrote the novels on which Reichardt’s Old Joy (2006), Wendy and Lucy (2008), Meek’s Cutoff (2010), and First Cow (2020) were based. But much like Reichardt’s Night Moves (2013), which she co-wrote with Raymond from an original idea, Showing Up didn’t originate with Raymond’s source material. The filmmakers considered a biography of Canadian painter Emily Carr, who, in the early twentieth century, built a small apartment house in hopes of generating income and supplying her more time to paint. But Carr turned out to be a famously lousy landlord, and worse, too much of a celebrity in her homeland for the small-scale character study the filmmakers had in mind. Most artist biographies, such as Basquiat (1996) or Pollack (2000), depict an artist’s life as a series of winning exhibitions and personal lows. But art is about hard work, managing relationships, and finding or making the time to create. So the film changed into a fictional account of a regional artist, part of a community of creatives orbiting around Portland’s Oregon College of Art and Craft (OCAC), which closed a few years prior to filming. Given its subject matter, Showing Up doesn’t have the same ponderous ideas about Nature and capitalism found in Reichardt and Raymond’s previous collaborations, but it takes place against the same Oregon backdrop.

Lizzy lives in an apartment with her cat named Ricky. When we first meet her, she’s preparing to work in her studio, walking around the house in Crocs and fussily planning her day. Lizzy has a show in one week, and there’s so much to do before then. But her life is full of delays and annoyances that keep her from making progress. For instance, Ricky wants to be fed, but he’s out of food. Lizzy claims his hungry meowing threatens to “ruin my workday” when she’s forced to leave home for the store. There’s also the matter of a broken water heater. Her landlord, Jo (Hong Chau), a fellow artist at OCAC and something of a friend, has promised to replace it. But Jo has two shows of her own to prepare and a tire swing to hang, leaving Lizzy unable to shower. Lizzy also has a day job as an accountant and graphic designer at the college; her sculpting doesn’t pay. Few artists working in this bohemian collective—who create yarn bodysuits, take courses on “Thinking and Movement,” and generally explore the limits of their expressive means—can survive on their passions alone. But like Lizzy, their art is their fuel and only topic of conversation. When they talk, it’s not “How are you?” It’s “How is your latest project coming along?”

Showing Up marks Reichardt’s fourth collaboration with Williams after Wendy and Lucy, Meek’s Cutoff, and Certain Women (2016). Williams makes another transformation here, carrying herself in the hunched manner of someone who spends her time slouched at a computer or over her sculptures, her darkened eyes stuck in an intense concentration. Lizzy seldom says goodbye after conversations and rarely smiles. She’s a perfectionist beholden to her own standards, evidenced when she takes her sculptures to the college’s kiln, overseen by the easygoing Eric (André Benjamin), and one of them comes out burned. Eric suggests that the burn adds something to the piece. “Not really,” Lizzy remarks, disappointed. Williams plays the character just this side of prickly and unlikeable, demonstrated by a Save the Cat! moment when Ricky wakes Lizzy in the middle of the night, having caught a pigeon. She sweeps up the injured bird in a dustbin and cruelly dumps it out the window. “Go die somewhere else,” she tells it. But the next morning, Jo finds the pigeon and, together with Lizzy, wraps its broken wing and safeguards the bird in a cardboard box. Lizzy keeps the cause of the injury to herself, and what at first is the annoying task of watching the pigeon becomes her increasing need to protect and care for her cat’s would-be victim.

Showing Up marks Reichardt’s fourth collaboration with Williams after Wendy and Lucy, Meek’s Cutoff, and Certain Women (2016). Williams makes another transformation here, carrying herself in the hunched manner of someone who spends her time slouched at a computer or over her sculptures, her darkened eyes stuck in an intense concentration. Lizzy seldom says goodbye after conversations and rarely smiles. She’s a perfectionist beholden to her own standards, evidenced when she takes her sculptures to the college’s kiln, overseen by the easygoing Eric (André Benjamin), and one of them comes out burned. Eric suggests that the burn adds something to the piece. “Not really,” Lizzy remarks, disappointed. Williams plays the character just this side of prickly and unlikeable, demonstrated by a Save the Cat! moment when Ricky wakes Lizzy in the middle of the night, having caught a pigeon. She sweeps up the injured bird in a dustbin and cruelly dumps it out the window. “Go die somewhere else,” she tells it. But the next morning, Jo finds the pigeon and, together with Lizzy, wraps its broken wing and safeguards the bird in a cardboard box. Lizzy keeps the cause of the injury to herself, and what at first is the annoying task of watching the pigeon becomes her increasing need to protect and care for her cat’s would-be victim.

Lizzy brings to mind the young Sammy Fabelman from Steven Spielberg’s autofictional drama from last year, The Fabelmans, in which Williams played Sammy’s creatively repressed and flighty mother. A key scene in that film finds Sammy’s actor-uncle Boris (Judd Hirsch) telling the boy, “We’re junkies. Art is our drug. Family, we love. But art—we’re meshuga for art.” Like Sammy, Lizzy is compelled by her work. Everything else gets in the way, even the support of other artists—she does not show up for Jo’s show, for example. Still, her relationships supply the emotional conflict that inspires her to create, so she needs them. At the college, she reports to her mother, Jean (Maryann Plunkett), a pragmatic sort who glimmers with the energy of a former nonconformist. Lizzy’s dad, Bill, played by Hirsch no less, has retired from a notable career in pottery; now he hosts random, mooching houseguests from Canada (Amanda Plummer, Matt Malloy). Lizzy also makes time to visit her “genius” brother, Sean (John Magaro, star of First Cow), whose paranoid ideas and backyard digging raise alarms, distracting her from making progress on her rough, aching sculptures (made by Portland-based artist Cynthia Lahti).

Working with cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt, who has been shooting the director’s films since Meek’s Cutoff, Reichardt delivers her brightest film yet in visual terms. Shot on location in Portland, the white studios and college classroom spaces, revitalized inside OCAC for the production, present a sharp contrast to Reichardt’s usual earthy palette. Even Blauvelt’s widescreen frame opens up the narrative next to the Academy ratio often used in the director’s work. Showing Up is also a carefully paced film, with the filmmaker serving as editor, as usual, to create shots that linger and appreciate the artistic process and art on display. Some might call the story slow, except those who can relate to Lizzy’s fixation on her artwork might find the proceedings urgent and comically nerve-racking—Reichardt’s equivalent to the tortured anxiety seen in Joel and Ethan Coen’s A Serious Man (2009). Fortunately, Ethan Rose’s largely electronic score, supplemented by meditative flute pieces performed by Benjamin, avoids turning the film into a pressure-cooker experience. But there’s a measured escalation until Lizzy’s exhibition that demonstrates Reichardt’s control over her character and the film’s quiet yet squeezing tone.

Through Lizzy, Reichardt and Raymond characterize artists as people who can become so driven as to have tunnel vision. Lizzy takes time off from her day job to finish her art, even though it’s not earning her a living, and pulls an all-nighter to complete her show pieces. Still, she remains shortsighted, doggedly so when her focus on her sculptures prevents her from making the social connections that could lead to something more substantial in her creative ambitions. A visiting artist and known success in New York makes attempts to talk to Lizzy, but the protagonist’s distracted demeanor will likely stall any progress. Meanwhile, Lizzy wonders how Jo has it all “figured out,” enough to achieve some notoriety in the community—or certainly more than Lizzy. Chau plays Jo as exceedingly patient and confident, often ignoring Lizzy’s most unpleasant and compulsive behavior—until Lizzy’s quiet aggression bursts into an expletive-laden voicemail. And while Jo remains frustratingly too preoccupied with her exhibition (amusingly called “Astral Hamster,” with artworks supplied by Michelle Segre) to fix her renter’s water heater, she at least shows up to Lizzy’s show: a nervous comedy of errors, including fussy arguments about cheese, family bickering, and at least two flights from the scene.

Through Lizzy, Reichardt and Raymond characterize artists as people who can become so driven as to have tunnel vision. Lizzy takes time off from her day job to finish her art, even though it’s not earning her a living, and pulls an all-nighter to complete her show pieces. Still, she remains shortsighted, doggedly so when her focus on her sculptures prevents her from making the social connections that could lead to something more substantial in her creative ambitions. A visiting artist and known success in New York makes attempts to talk to Lizzy, but the protagonist’s distracted demeanor will likely stall any progress. Meanwhile, Lizzy wonders how Jo has it all “figured out,” enough to achieve some notoriety in the community—or certainly more than Lizzy. Chau plays Jo as exceedingly patient and confident, often ignoring Lizzy’s most unpleasant and compulsive behavior—until Lizzy’s quiet aggression bursts into an expletive-laden voicemail. And while Jo remains frustratingly too preoccupied with her exhibition (amusingly called “Astral Hamster,” with artworks supplied by Michelle Segre) to fix her renter’s water heater, she at least shows up to Lizzy’s show: a nervous comedy of errors, including fussy arguments about cheese, family bickering, and at least two flights from the scene.

Doubtless, Reichardt—who teaches filmmaking on the side to make a living and afford health insurance—relates to Lizzy’s passion for her art, despite the many practical hurdles and personal torment it causes. An artist’s creation is like their child, and parents love their children more than anyone else (and other people’s children are often the worst). An artist will make every sacrifice to nurture their creation. So it’s curious that Lizzy comes to feel the same way about the pigeon—a sense of ownership and responsibility, even more than for her cat. Perhaps it’s guilt. Not even the vet, who redresses the broken wing and recommends a hot water bottle to keep the bird warm, cares that much. “That’s all?” Lizzy wonders. “It’s a pigeon,” the vet shrugs. Likewise, Lizzy’s sculptures won’t look like masterpieces to many viewers at first. They’re the equivalent of pigeons, to be met with an initial shrug; then again, the bird and the sculptures grow more fascinating upon examination. When those globs of gray clay emerge from the kiln in bright colors and contours capture the light, Lizzy’s artwork glimmers, for her most of all. In the final shot, which once again adopts the pigeon’s-eye-view of Lizzy, Reichardt reminds us that Showing Up is a brief glimpse into an artist’s life, portrayed as an almost pathological need to create. And while not always easy to understand, she greets her subject with an awareness that, to some degree, every artist exists in a world unto themselves, and everyone else is an outsider.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review