Sharp Corner

By Brian Eggert |

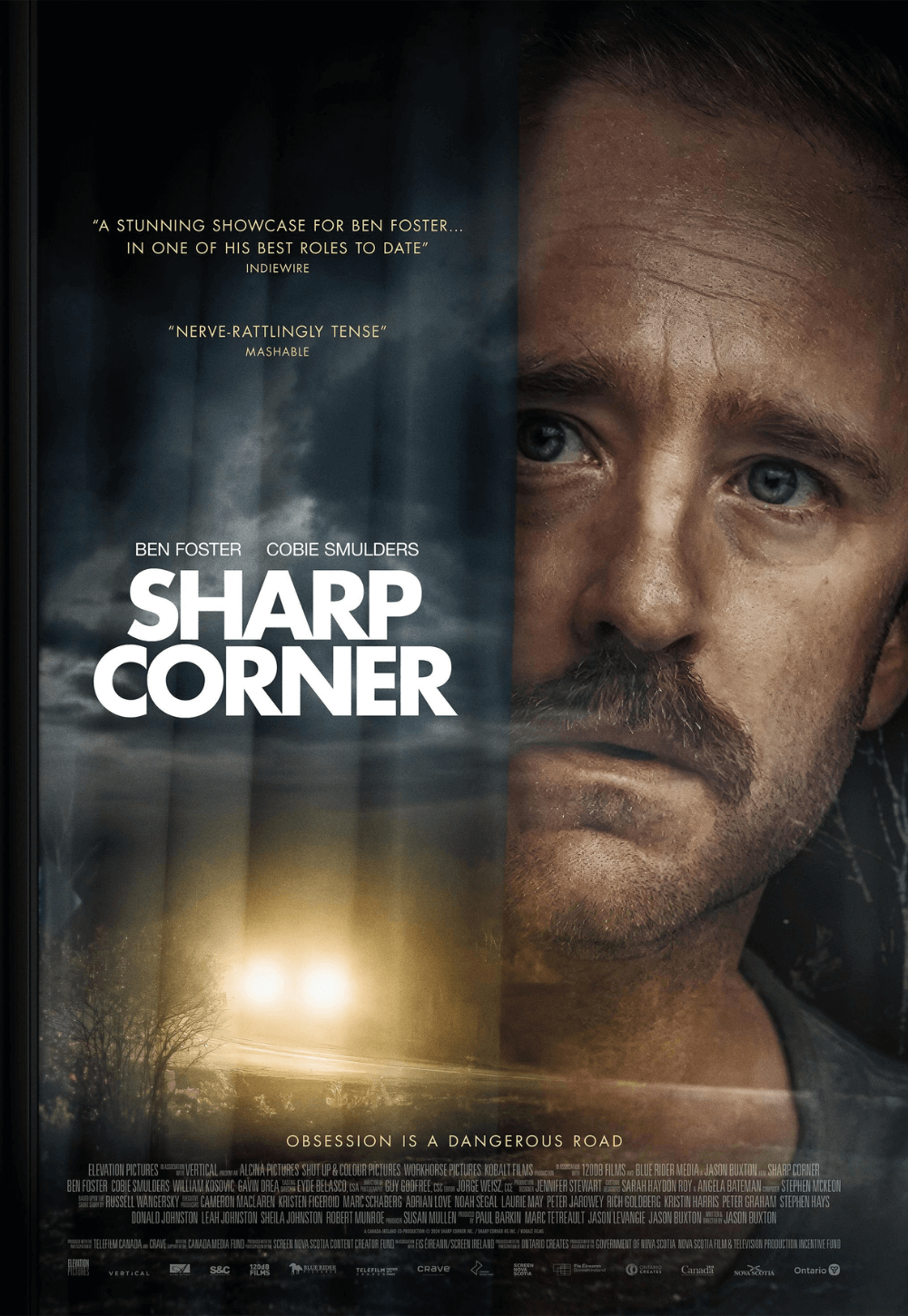

“Are men okay?” That’s the question asked in many think pieces and social posts lately. It’s also at the heart of Sharp Corner, a thoughtful character study starring Ben Foster, whose performance is outstanding. The film is about a family man who has lost interest in his cozy, conventional domestic life. He unconsciously yearns for disruptions and eventually creates a scenario that sabotages his life, yet it gives him a warped sense of purpose. Jason Buxton, writer-director of the award-winning Blackbird (2012), based his film on “Sharp Corner,” a short story in Russell Wangersky’s 2012 collection Whirl Away. In the press notes, Buxton says his film is about the “fragile nature of contemporary masculinity,” and the filmmaker explores this topic not only with initial touches of emotional realism but a continued sense of unraveling psychology that Foster plays to perfection.

Still, the question of whether men are okay today isn’t a new one. People of all demographics have struggled with questions of identity and whether they fit into the stifling, socially prescribed definitions for who they’re supposed to be. There are times in history when people buckle against the expectations thrust upon them, usually in eras of strict social dogma. Sharp Corner reminded me of Revolutionary Road (2008), which takes place in the late 1940s after World War II and finds a couple (Leonardo DiCaprio, Kate Winslet) realizing the American Dream isn’t quite the idyll it’s cracked up to be. Buxton’s film takes place in Canada, and however appealing life in Canada seems at the moment compared to their neighbors to the South, there’s no shortage of existential crises in Canuck Country. Sharp Corner unfolds in equally disturbing and tragic ways as Revolutionary Road.

The film opens with Josh McCall (Foster), a corporate sales-something-or-other who’s outwardly normal—whatever that means—complete with the unofficial uniform of the average white male yuppie: a blue button-down shirt and tan khakis. Josh moves from the city to the country with his wife, Rachel (Cobie Smulders), a mental health professional, and their young boy, Max (William Kosovic). On the first night in their new home, which is “brimming with possibilities,” they discover why they got such a good deal and why the property sat on the market for six months. Their large, picturesque house sits next to a road that turns suddenly. A traffic sign warns of the upcoming curve on Wakerley Road, but it’s obscured by foliage. And as Josh and Rachel christen the dining room on their first night, a tire crashes through their window and interrupts their lovemaking. A drunk teen has slammed his car into a tree in their front yard and died.

Everyone deals with this incident—and the many accidents that follow—differently. Max shows no immediate external signs of trauma, but Rachel soon discovers troubling evidence of his concealed anxiety. She initially thinks about putting up a guardrail or more road signs before ultimately wanting to sell the house and move. But Josh, through some unclear logic writhing around in his head, becomes obsessed with the passing cars and roadside memorial near his lawn. The whoosh of every vehicle draws his attention away from the family, his mind drifting mid-conversation toward the road. His nightly glass of wine with dinner becomes a bottle. In the evening, he sits on the porch, watching cars turn the corner. Does he dread another crash? Does he hope for another one, like the protagonist in David Cronenberg’s Crash (1996)? At work, he loses interest, preferring to search the online profiles of accident victims for reasons he never articulates. Some part of him wants to save the next victim, so he takes a CPR class. Another part of him hopes he can use his new training.

The portrait of Josh and Rachel’s marriage is complex and avoids banalities and clichés. She encourages him to attend therapy for his recent behavior, and he shares with his therapist twisted logic for how Rachel signing their son up for taekwondo classes somehow means she’s responsible for Max witnessing a fiery accident. Josh’s self-defense mechanisms have steeped him in delusion. Still, Rachel can seem unsympathetic, or maybe the movie’s way of placing us in Josh’s subjectivity. When she complains that he’s insensitive to the family’s feelings about the road, she ignores his witnessing multiple people die before his eyes in their front yard. Whatever deeper, unspoken issues exist in their marriage, this situation overshadows and amplifies them.

Foster is a wise choice to play Josh. He has played hyper-masculine types in 3:10 to Yuma (2007) and Hell or High Water (2016), but he’s also delivered wounded and sensitive characters. As Josh, his choices are subtle and stereotypically unmasculine, from his high, agreeable voice to his almost fey body language. His mustache and talk about his golf game seem like affectations; his male pattern baldness is another of the universe’s jabs at his fragile ego, which he defends with an eerie exterior confidence. Foster lends Josh the mannerisms of a serial killer in disguise. Something about his glazed-eyed nonchalance comes off as creepy. Underneath Foster’s performance, composer Stephen McKeon’s haunting score recalls the brooding notes of Howard Shore’s work with Cronenberg, suggesting a darkness under Josh’s surface. And as the film carries on, d.p. Guy Godfree’s crisp images on location in Nova Scotia capture the home’s fleeting domestic bliss that gives way to a chilling reality.

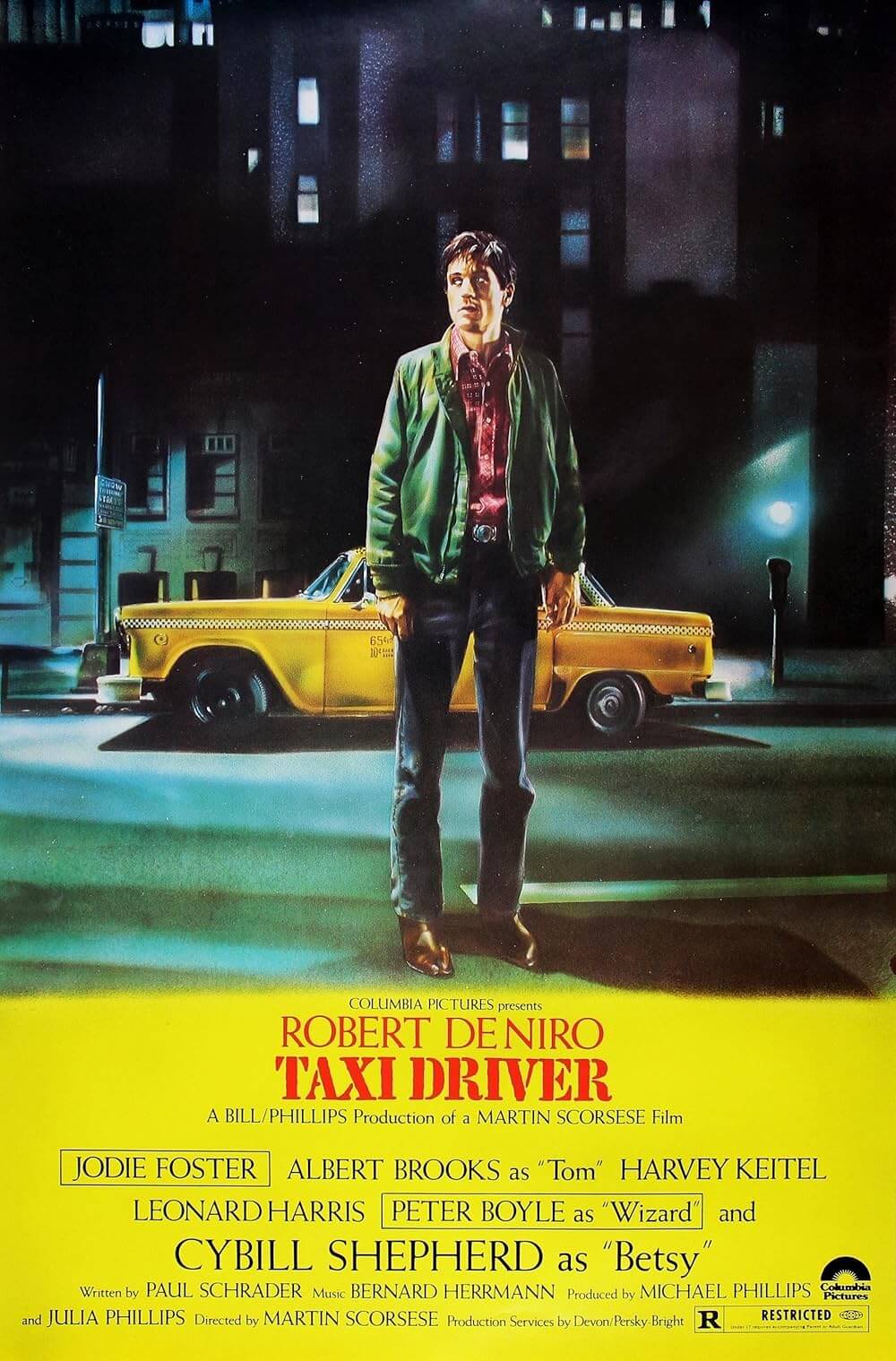

Buxton’s screenplay has been interpreted as a sociological investigation into male identity, with Josh feeling alienated by his meaningless job, inability to win a prize for Max at a carnival strong-man game, and other examples that build into a larger picture. But this situation seems too specific to represent a larger masculine crisis, whereas this year’s Friendship better fits into a sweeping commentary on how some of us lack that male bonding skill. However, any such broad generalizations about male identity are absurd. People are individuals. What does it gain by putting them in generalized categories? Instead, Sharp Corner feels akin to Taxi Driver (1976) and Saint Maud (2019), where the progressively warped behavior of the protagonist could have countless sociopolitical implications, more compelling as an interpretable case study that leaves questions for the audience. And like those films, Sharp Corner feels like it will continue to be talked about because it respects the audience enough not to answer its questions.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review