Rubber

By Brian Eggert |

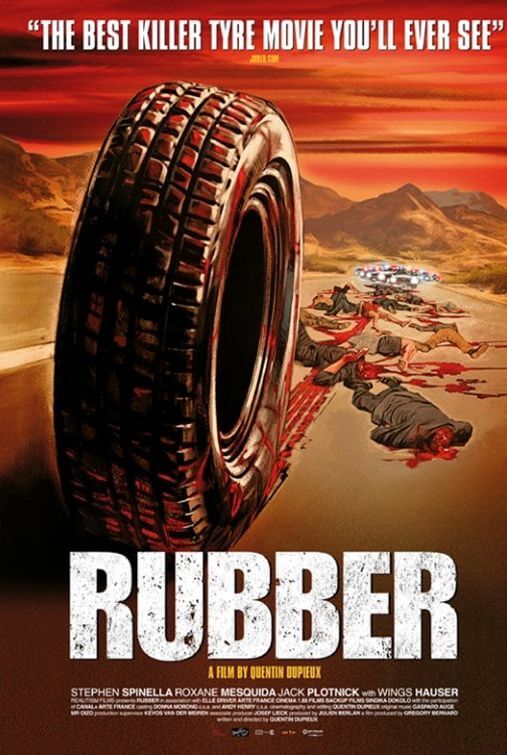

For a critic, there’s almost nothing worse than a filmmaker who thinks they’re being clever, but isn’t. Writer-director Quentin Dupieux makes this very mistake with Rubber, a film that’s advertised as a slasher movie where the killer is a tire come to life. Billed as “Bob the tire”, he emerges from the sand, wordless and faceless like any other tire, only to discover a taste for blowing up objects (some inanimate, some not) with his apparent telekinetic abilities. Bob rolls into a nearby desert town and wreaks havoc on the locals by exploding a number of heads. And while there’s enough potential in that playful genre riffing premise alone, through insultingly transparent metaphors Dupieux instead soapboxes about the relationship between movies and their audience.

In the first scene, Lieutenant Chad (Stephen Spinella) emerges from a police cruiser trunk, breaks the fourth wall, and tells us that this film is about how movies so often provide “no reason”. Using a dozen examples from cinema history, Lt. Chad recounts how viewers just accept the illogical because a movie tells them to do so. For example, we accept that Bob is a killer tire because that’s what the movie shows us—like so many movie villains, he is merely a force of Nature, pure and evil, and as viewers we know he is bad, and that’s enough. Dupieux claims his film is an homage to this “no reason” phenomenon, but then drowns the hilarious, satiric simplicity of his killer tire scenario with even more nonsensicalities that fall flat. As a result, I found myself wishing Dupieux had simply made a slasher movie with a tire instead of this pompous nonsense.

Watching Bob’s story through binoculars from afar is a generic test audience comprised of various stereotypes. They’ve been assembled by a nerdy associate (Jack Plotnick) working for an unseen “Master”. But as long as the test audience watches, the players in Bob’s story, such as Lt. Chad and a French damsel (Roxane Mesquida), are forced to act it out, like prisoners of a bad genre flick, which in turn becomes a movie-within-a-movie. They watch and point out plot holes or lags in the pace, and sometimes our comments on Rubber mirror theirs. The actors in Bob’s story attempt to poison the test audience, because once they’re dead they don’t have to act anymore, but one stubborn viewer (Wings Hauser) survives and announces his determination to see where the killer tire story goes.

In a way, Rubber borders on a non-narrative approach by being merely a series of observations about cinema tied together in a loosely stitched whole. None of this strikes an emotional chord because there is no plot to follow. We watch unengaged, deciphering Dupieux’s facile metaphors as they relate to the industry. The characters are not characters at all, but rather elements in the film’s ongoing argument. Yet, only a small portion of this 82-minute film concerns the hoity-toity observations on cinema. For the film’s majority, Dupieux, who also serves as cinematographer, follows around the tire with his camera as it rolls through the desert. It can be said that a tire has never looked so good, as Dupieux displays impressive control over his camera and the tire’s continuous, almost personified rolling. But as viewers take in about five minutes of this, we get the idea already and want Dupieux to move on.

However illogical the reasons may be in your standard Hollywood fare, the usual arbitrary plot connections have more salience than the uninvolving observations made and method used in Dupieux’s avant-garde mess. In the end (if you can make it that far), viewers will be left wondering what they’ve just watched. There seems to be more going on than the proposed “homage to ‘no reason’” as explained in the first scene. So what then? A censure of Hollywood for taking advantage of its audience’s familiarity with formula? A paradoxically illogical movement toward logical, reason-fuelled filmmaking? (Wouldn’t that undermine the incredible power of cinema, which Dupieux seems to admire so much?) No doubt there’s a noble (if muddled) message in here somewhere about how Hollywood relies too much on conventions, and if we just stopped watching the film industry’s recycled garbage, they’d stop making it. But if the answer to Hollywood’s lacking creativity is Rubber, then I’d gladly watch a few more formulaic genre movies in its place.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review