In the Loop

By Brian Eggert |

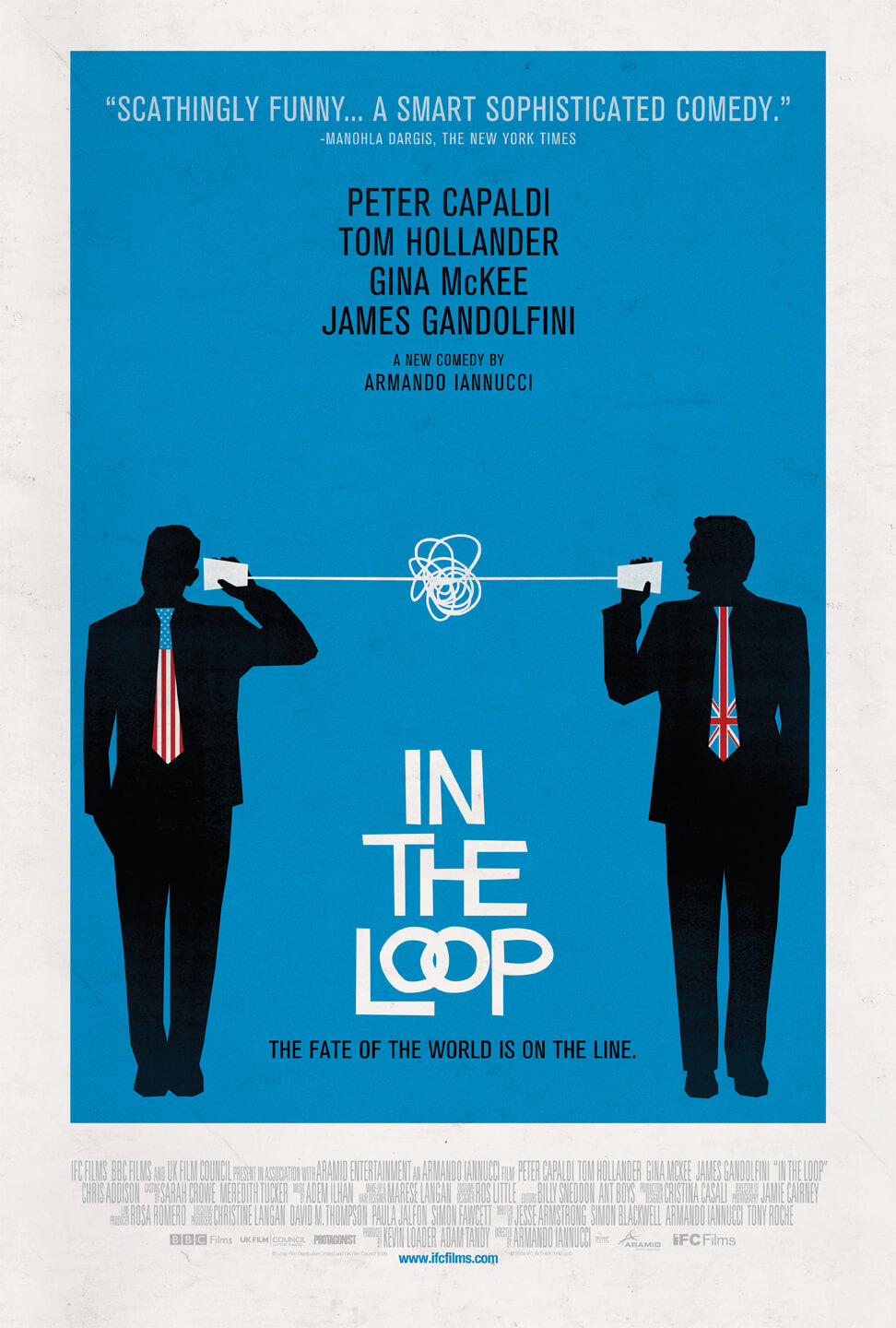

Scathing ammunition in the form of harsh insults, media manipulation, and ubiquitous bureaucracy fuel In the Loop, a blacker-than-black satire on political spin doctors. This witty, blisteringly funny comedy suggests wars come to be through a mind-numbing procession of fake committees, altered reports, know-nothing assistants, and verbal missteps. Thanks to the mostly British cast, the ruthless spewing of nasty, hilarious, deathly sharp dialogue somehow remains eloquent and articulate, offering a slice of moviegoer bliss for those versed in the language of sarcasm. An extension of the abbreviated BBC series The Thick of It, the film draws from the show’s many writers and adept director, Armando Iannucci, back to the political coppice for another go. No worries if another of the BBC’s excellent productions has eluded you—I’ve never seen the show either. I also haven’t laughed so hard at a movie this year. And this isn’t the kind of riotous laughter that follows the singing penis in Brüno, nor the awe-driven laughs of The Hangover. Instead, it’s a durable, smartly written assemblage of highly quotable material that will continue to be funny no matter how many times you see it.

The story follows lowly sub-minister Simon Foster (Tom Hollander), who makes the mistake of remarking on the “unforeseeable” possibility of war in the Middle East spearheaded by the United States. Of course, the movie means Iraq, but it doesn’t say it, rendering the subsequent war-mongering timeless. Malcolm Tucker (Peter Capaldi), foul-mouthed communications director to the British prime minister, tries to help Foster backtrack on his statement, to walk the line of officialdom rather than take a side. Veteran underling Judy (Gina McKee) and naïve newbie Toby (Chris Addison) help the minister along as much as they can too—the latter by becoming Foster’s bro-speak friend. Foster is too thick to survive in his own cruel arena, however, and each time he opens his mouth, it just gets worse.

“To walk the road of peace, sometimes we need to be ready to climb the mountain of conflict.” Foster’s nonsensical attempts like this to recover from his initial slip-up register as idiotic to the Brits (“‘Climbing the mountain of conflict’? You sounded like a Nazi Julie Andrews,” Tucker comments), but the Americans, desperate for war, find it utterly inspirational. On Capitol Hill, a slew of people with big names and even bigger desks play Battleship over going to war. The crass Linton Barwick (David Rasche) uses an actual grenade as a paperweight; guess which side he’s on. Then there’s Assistant Secretary of State Karen Clark (Mimi Kennedy), who exposes Barwick’s secret war committee to anti-war teddy bear General George Miller (James Gandolfini). To abate the idea of war in the eyes of the media, they consider leaking Clark’s in-house report “Post War Planning: Parameters, Implications and Possibilities,” known through the acronym PWPPIP, written by her aide Liza (Anna Chlumsky—yes, the one from My Girl).

Meanwhile, Foster finds himself placed into important meetings filled with press and high-profile people, sitting in the back row as silent “room meat.” Because his “unforeseeable” comment raises such hullabaloo, Clark and Miller seek him out to stop Barwick and Tucker’s back alley political deals from starting an unnecessary war. Still, Foster worries too much about his career to make the right decision. In the movie’s funniest scenes, Foster gets pulled aside to handle grievances from an ornery constituent (played by Steve Coogan) troubled by the crumbling brick wall next to his mother’s garden. Never mind the impending war—there are neighborhood affairs nipping at his ankles, none of which Foster can handle.

Meanwhile, Foster finds himself placed into important meetings filled with press and high-profile people, sitting in the back row as silent “room meat.” Because his “unforeseeable” comment raises such hullabaloo, Clark and Miller seek him out to stop Barwick and Tucker’s back alley political deals from starting an unnecessary war. Still, Foster worries too much about his career to make the right decision. In the movie’s funniest scenes, Foster gets pulled aside to handle grievances from an ornery constituent (played by Steve Coogan) troubled by the crumbling brick wall next to his mother’s garden. Never mind the impending war—there are neighborhood affairs nipping at his ankles, none of which Foster can handle.

Shot with zooming hand-held photography, the camerawork gives the movie an on-the-scene air. Fans of The Office and The West Wing should feel right at home following characters down bland hallways and standing in drab offices while listening to endless tirades and tangents unfurl. A pale-colored presentation leaves Washington D.C. looking quite banal through whatever scratchy filters cinematographer Jamie Cairney uses. It feels less like cinema and more like peering into the actual events that preceded the invasion of Iraq, complete with disregard for facts and absurd last-minute changes in political positions. Intentionally scrambled like a mess of crossed wires, the plot changes gears every few minutes and doesn’t wait up for its audience. That’s part of its brilliance. Consider how quickly world events unfold on CNN, and then imagine that progress dramatized and condensed into a feature film. Here you have the complication behind the movie’s scenario, which is not so much something that requires you to follow it; rather, it hopes to lose you in the flustered mayhem, because what sane person could stand or follow this madness?

The film’s greatest strength resides in the endless stream of cutting dialogue. Comparable to David Mamet’s acrid, so-wounding-its-funny discourse from Glengarry Glen Ross, the movie will prove quotable not to the hordes of drunken fratboys usually citing lines from this week’s popular comedy but to a more selective audience. There’s some perfection in Barwick saying, “I can’t stand to see a woman bleed from the mouth. It reminds me of that Country & Western music, which I cannot abide.” Or Tucker spouting out one of his vindictive diatribes: “This is a government department, not some fucking Jane fucking Austen novel!” An obvious comparison to In the Loop is Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (“Gentlemen, you can’t fight in here! This is the War Room!”). The result comes off on a much smaller scale, but both are propelled by fast-moving dialogue and dark subject matter that forces us to laugh at horrible things. Both weigh the absurdity of our political system against world-sized conflicts that would typically demand utter seriousness, resolving that the process unfolds like a screwball comedy and that those in charge of the most vital decisions are either too dense or too wicked to be in a position of power.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review