Primate

By Brian Eggert |

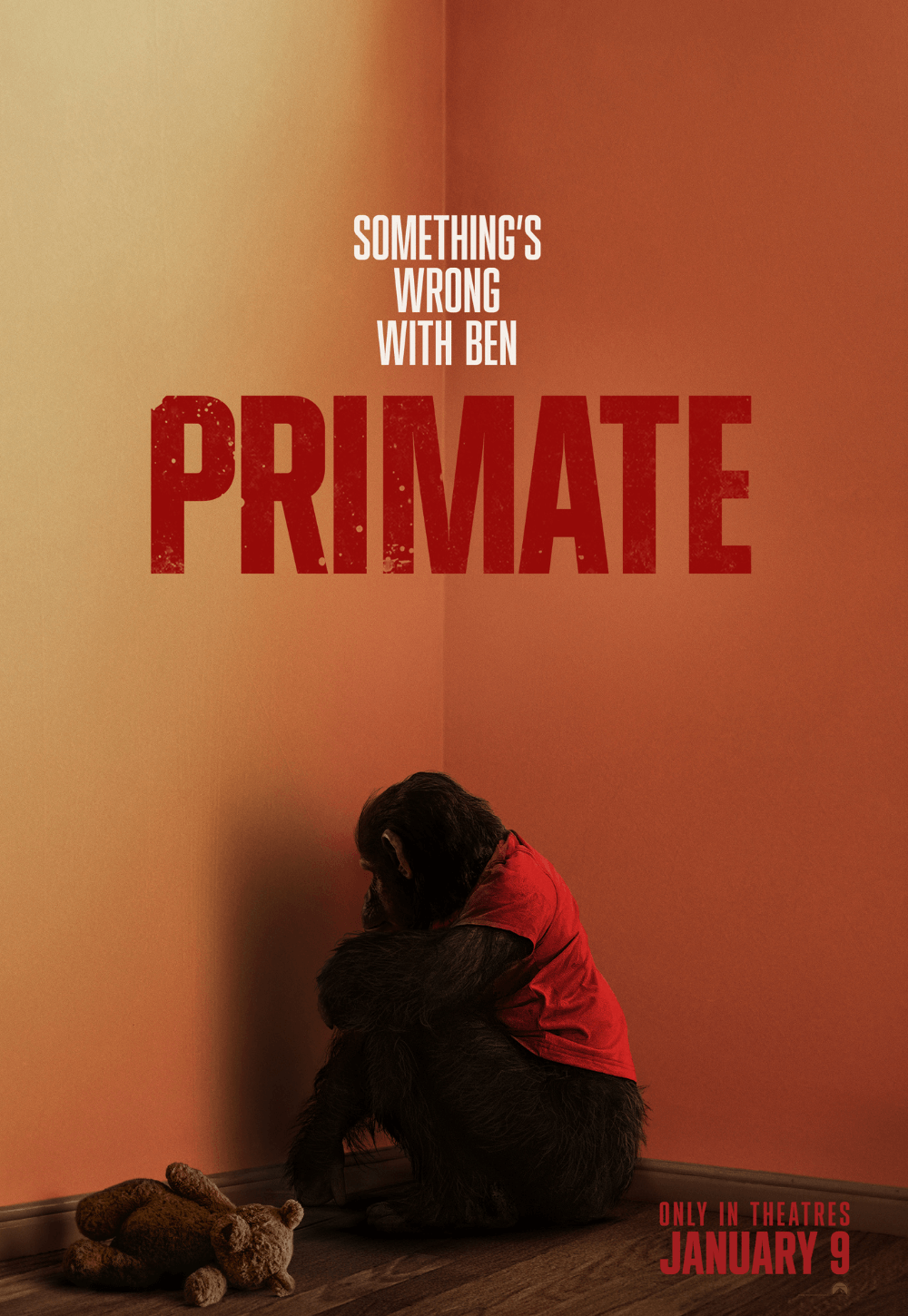

Shield your face and gird your loins, because Johannes Roberts’ Primate is a merciless when-animals-attack flick. With a simple premise and an assured execution, the writer-director delivers a gnarly, brutal experience about a chimpanzee with rabies who ravages a group of twentysomethings in a lavish Hawaiian home. Roberts has never tried to disguise his admiration for, or homages to, the horror movies of yesteryear, especially the work of John Carpenter—see his underrated The Strangers: Prey at Night (2018)—and his latest is no exception. Primate plays like a blend of Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) and Lewis Teague’s Cujo (1981), delivering a pseudo-slasher movie where the killer is an intelligent animal who, besides having incredible strength, can understand human language and even communicate back. That makes the proceedings all the more chilling and uncanny. At just under 90 minutes, it’s a gruesome pressure-cooker experience and not for the squeamish.

To be sure, when the first scene of your movie features someone’s face getting ripped off, it’s evident the filmmaker isn’t playing around. That teaser of things to come gives way to Lucy (Johnny Sequoyah), who, along with her best friend Kate (Victoria Wyant) and Kate’s unwelcome third-wheel friend Hannah (Jessica Alexander), returns home to Hawaii. A year has passed since Lucy’s mother, a linguistics professor trying to bridge animal-human communication, passed away from cancer, leaving a hole in her remaining family: Lucy’s younger sister Erin (Gia Hunter) and their widowed father, Adam (Troy Kotsur), a deaf author who writes best-selling novels with titles such as Silent Death. That’s how the family can afford their picturesque house, with a swimming pool ill-advisedly situated on a steep oceanside precipice—and you just know someone’s going off that cliff.

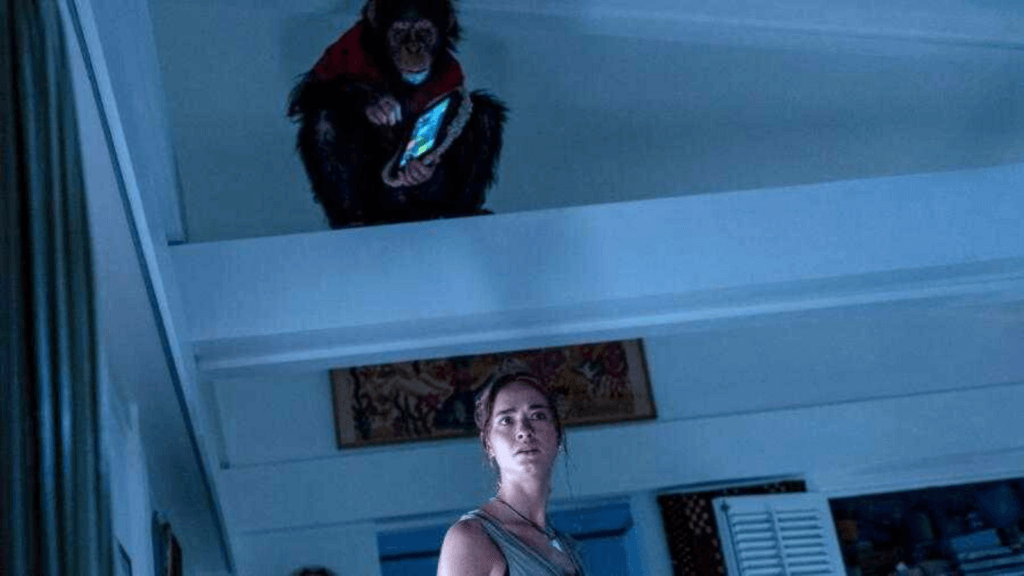

The house has been modified for the family’s pet chimp, Ben, whom Lucy’s mother adopted to train in ASL and a digital communication pad programmed with common English phrases. Roberts doesn’t spend much time establishing these characters or their personalities before the carnage starts. By the time Lucy gets home, a mongoose has already bitten Ben; however, no one suspects rabies because that virus doesn’t exist in Hawaii due to strict quarantine laws regarding animals. When Adam heads out to a book signing, he leaves the young people at home to drink, smoke pot, and invite some boys over. But it doesn’t take long for Kate to observe, “There’s something wrong with Ben.” Sure enough, the usually gentle chimp growls and foams at the mouth, having escaped from his enclosure. After a violent outburst, Ben corners Lucy and company in the pool—a refuge since chimps cannot swim—and every attempt they make to escape only angers the chimp further.

In a roundabout way, Primate’s setup recalls Roberts’ earlier hit, 47 Meters Down (2017), about divers trapped in a cage on the ocean floor in shark-infested waters. Both involve young women isolated in water, hunted by an animal. And just like that movie, Roberts has no interest in turning this into a social commentary or offering a lesson. He avoids both questioning the ethics of owning a chimp and remarking on the social and economic implications of outsiders buying up land in Hawaii. There’s no pretense or greater meaning behind the movie that I could discern, nor even a thematic thrust. I suppose the family’s bond will strengthen as a result of this trauma, bringing Lucy and Erin closer to their father in the absence of their mother. But that’s barely addressed. Instead, Primate is content as a relentless killer-animal movie that immerses the viewer in a breathless moment-to-moment immediacy. That’s enough.

Ben is a frightening character. Besides jaw removals and fatal thrashings, the chimp taunts his victims with malicious cackles and taps on his voice pad, such as pressing “Dead” on repeat. And unlike the recent Planet of the Apes series, which employs motion-capture CGI to render photorealistic, albeit obviously digital apes, Roberts relies on practical effects augmented by the occasional digital touchup. Actor and movement specialist Miguel Torres Umba plays Ben in a flawless chimp suit that looks better than any I’ve seen before. Even so, Roberts and cinematographer Stephen Murphy make the wise choice to show Ben obscured or out of focus in several sequences, recalling moments in Halloween that let the viewer’s imagination fill with dread at a shadowy figure moving in the background. The Carpenterisms continue with Adrian Johnston’s music, a slick homage to the synth scores by Carpenter and Alan Howarth. Roberts also follows the slasher-movie mode, with POV shots from Ben’s perspective and a sequence in which Ben corners two survivors in a closet.

Primate may have benefited from another draft of the screenplay to give the material some substance and the characters some depth, but, regardless, Roberts achieves a blood-curdling, efficient B-movie. It’s simple, straightforward, and effective. Even though the characters remain one-note, Sequoyah and especially Kotsur have a genial screen presence that endears their characters to us. Early, chummy scenes of the family signing and promising to spend more time together lead to an earned emotional release in the finale. Roberts has little use for the other humans, particularly a couple of belching douche bags who show up late, apart from adding their numbers to the body count. With modest ambitions, Roberts lands another memorable if simple-minded horror movie that does everything it sets out to, and it’s loads of gory fun.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review