The Definitives

Ganja & Hess

Essay by Brian Eggert |

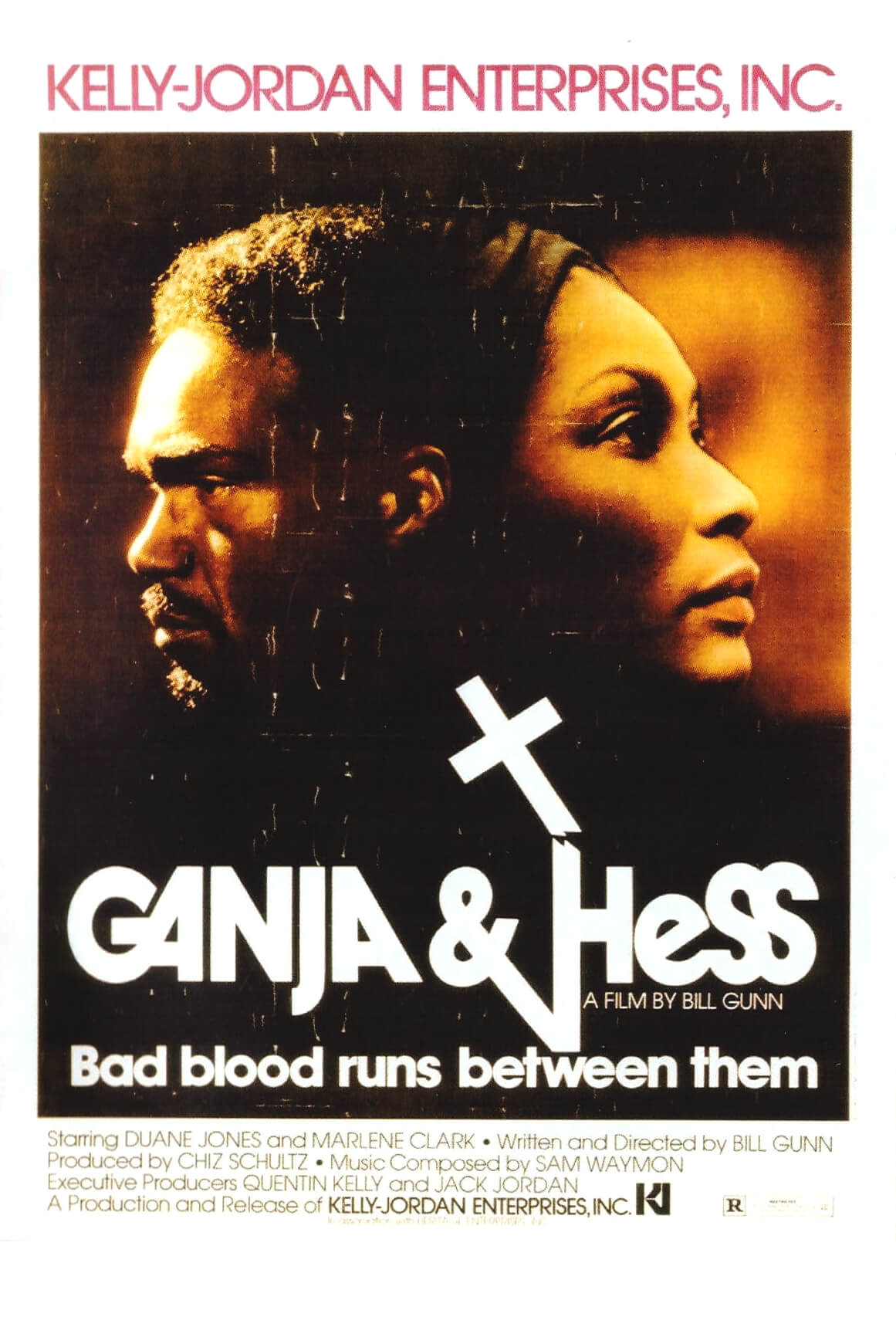

Ganja & Hess is the phantasmagoric outpouring of a singular artist whose voice cannot be easily categorized. Written and directed by Bill Gunn, the 1973 film has a loose affiliation with vampires and Blaxploitation while confronting mainstream ideas about racial representation, sexuality, and cinematic tradition. For years, the film existed in relative obscurity, severely re-edited and distributed as a throwaway hunk of schlock entertainment. But a twenty-first century restoration by The Museum of Modern Art and The Film Foundation has led to a full appreciation of this surreal, visceral, yet intellectual work of filmmaking. Without question, Gunn’s individualism drives this picture. Ganja & Hess is thoughtful, full of haunting, uncanny imagery and formal experimentation, and wholly unconventional in its making. It offers a potent blend of alienation, desire, and self-possession that feels like a personal statement. However, its fluid exploration of these themes is rooted in the senses, sometimes better felt than reasoned or summarized. Gunn’s moody and rebellious work of independent cinema is not unlike its characters, marked by its fragmentation, layers, and deviations. No matter how unpolished it sometimes seems, its urgent filmmaking supplies a charge that makes the experience vital and unforgettable.

Critic James Monaco described Ganja & Hess as the “great underground classic of Black film, and, I think, the most complicated, intriguing, subtle, sophisticated, and passionate Black film of the seventies. If Sweet Sweetback is Native Son, Ganja and Hess is Invisible Man.” The story, however, remains elusive, and its details must occasionally be gleaned from close observation. Hess Green (Duane Jones, from 1968’s Night of the Living Dead), a doctor of anthropology and geology, researches the Myrthia tribe, an ancient African culture that “had a need” for blood. Hess is a man of culture and means—he’s multilingual and fluent in art, both African and Western. He wears expensive clothes and travels in a Rolls Royce, driven by his chauffeur Luther (Sam Waymon), a part-time minister. He lives in a massive home isolated on a sprawling estate in Westchester County, New York, where he hosts elegant parties. No longer married, he has a son who is away at a boarding school. Tending to Hess’ every need is Archie (Leonard Jackson), the estate’s butler and Hess’ personal attendant. But Hess Green, Luther tells us in voiceover, is also addicted to blood.

When Hess invites his new assistant, George Meda, played by the director in a raw performance, to stay at his estate until Meda can arrange some place of his own, Hess is confronted by an unhinged man. Meda has attempted suicide in the past, and late in the evening, Hess finds him sitting in a tree near a noose. Although he talks Meda down, later that night, his guest snaps and attacks him with a Myrthian dagger, then shoots himself in the chest. Hess should be dead, but instead, the dagger has passed along an ancient need. Hess awakes with a taste for blood and proceeds to drink Meda’s off the bathroom floor. He stores Meda’s body in the freezer and takes to robbing blood banks to satiate his new thirst. When that plan exhausts itself, he kills prostitutes. Before long, Meda’s wife, Ganja (Marlene Clark), arrives, looking for her husband, but she instead falls for Hess. The two enjoy a sensuous love affair, as Ganja upsets Hess’ routine in vital ways. They marry, and he soon changes her into an immortal. While Ganja acclimates, Hess grows weary of his lifestyle and seeks forgiveness from his minister friend. Hess ultimately resolves to end his life—reading the “guide to our destruction,” he learns that standing in the shadow of a cross means certain death—leaving Ganja to carry on as a Myrthian vampire.

The film’s author, Bill Gunn, was born in 1929 to a father who wrote music and poetry, and an actress mother who ran a theater company. They lived in a predominantly white, middle-class section of West Philadelphia, where Gunn felt his parents raised him “as if he were white and middle class,” according to a Cinéaste interview with friend Chiz Schultz, who produced Gunn’s screenplay for The Angel Levine (1970). Despite being well-read and cultured, Gunn never graduated high school. He floundered around for years, discovering himself as a Black and gay man, working odd jobs, and even joining the U.S. Navy for a short while. He soon landed in New York’s East Village, where he studied acting with Mira Rostova, the Russian performer who taught the method to Montgomery Clift. Gunn entered the same social circle as Marlon Brando and Elia Kazan; he understudied for James Dean’s role in The Immortalist at the Royal Theater. The two became personal friends, and Dean even painted Gunn’s portrait. Gunn acted in Broadway and Off-Broadway plays before heading to Hollywood, where he had a prolific career in television, appearing in shows like Naked City, The Outer Limits, and The Fugitive. By the late 1950s, he began developing his talents as a writer. He wrote seven plays in as many years starting in 1959, each performed on various New York stages. He also published two novels, including All the Rest Have Died in 1964, a semi-autobiographical story about a creative who returns to his Philadelphia home, feeling a part of neither the white world nor the Black one.

In the 1960s, Gunn started writing Hollywood screenplays, but many of them went unproduced. Harry Belefonte’s company hired him to adapt The Angel Levine from a short story by Bernard Malamud. In the movie, Zero Mostel plays an elderly Jewish man who prays for a miracle. His guardian angel, played by Belafonte, must convince him to put aside his racial prejudices before his prayers will be answered. Although Gunn shared screenplay credit with Ronald Ribman, it was enough to draw the attention of Norman Jewison, whose In the Heat of the Night (1967) had just won five Oscars, including Best Picture. Jewison was interested in Civil Rights-themed stories, and he hired Gunn to adapt Kristin Hunter’s 1966 novel The Landlord, which would become the directorial debut of Hal Ashby. In the film, released in 1970, Beau Bridges plays a privileged white snob who plans to buy a tenement building and evict the Black residents to make the building his own, though he’s soon drawn into their lives and becomes resentful of his narrow upbringing. The film became a moderate success, though Gunn remained frustrated with Hollywood and his lack of creative control. “I’ve liked every script I’ve ever written,” he told The New York Times in 1971. “I’ve hated every movie made from them.”

As a director, Gunn only made three features, and each had a troubled journey to the screen. His debut, Stop (1970), was greenlit by Warner Bros., which was struggling at the time and seeking out low-budget productions to keep costs low. Gunn’s story follows two couples who meet in Puerto Rico and, as described in Steve Ryfle’s profile of Gunn in Cinéaste, have a “four-way bonfire of infidelity, lust, drugs, deceit, and revenge ensues, venturing into then-controversial territory of gay and lesbian sex”—material that had not been present in Gunn’s script, but was added during the filmmaking process. Disturbed by the film’s provocative and erotic nature, which had been slapped with an X rating, Warner Bros. permanently shelved Stop and, to this day, have not made it available to the general public. Gunn continued writing scripts, including an unproduced Muhammad Ali biopic, before gaining the attention of producers Quentin Kelly and Jack Jordan, whose Kelly-Jordan Enterprises had purchased scripts from prestigious Black authors such as Maya Angelou and James Baldwin. Kelly and Jordan wanted Gunn to write a “black vampire film” to compete with American-International Pictures’ upcoming release called Blacula for 1972. The producers jumped at Gunn’s script of Ganja & Hess and gave him $350,000 to direct.

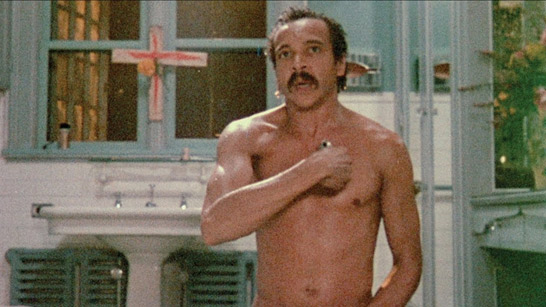

Given that his relatively inexperienced financiers were out of the country overseeing another production, Gunn had complete creative freedom shooting Ganja & Hess. But not unlike his experience shooting Stop, the result of his efforts didn’t resemble what was written. “It was a hugely entertaining piece that could have been black or white,” Kelly remarked about the script in 2010. “Bill Gunn was a terrific writer, but he wanted to direct it, and what he really wanted was to direct his own movie that had nothing to do with the script.” Shot on location at a New York farm in Super 16mm, Gunn’s film never mentions the word “vampire” or any derivations thereof. His style is defiantly uncommercial, filled with hypnotic music, occasionally meandering narrative details, and unfiltered, achingly vulnerable performances. Gunn’s naked presence onscreen arrives when Meda pours his heart out to Hess, while snot pours out of his nose, dripping onto his chest; his nakedness is literal in his final scene, when he strips down, bathes, and shoots himself in the heart. Although Ganja & Hess would not appeal to the masses, it fit nicely into a growing category of experimental cinema alongside the avant-garde films by Andy Warhol and Alejandro Jodorowsky. Still, it was hardly what Kelly-Jordan Enterprises had purchased.

Nevertheless, the film’s artiness didn’t stop the distributors from holding a major premiere at New York’s Playboy Theater in 1973, after which the critical establishment dismissed Ganja & Hess. In a particularly nasty review that shows a white critic unwilling to engage with Black subject matters, The New York Times critic A.H. Weiler called the film “black-oriented” and “ineffectually arty” for its “confusingly vague mélange of symbolism, violence and sex.” Though, Weiler is sure to comment on Clark’s “arresting appearance” either “dressed or nude.” Insensed, Gunn replied in a letter to the critic, published in the newspaper less than a month later. Gunn pointed out how Weiler’s plot summary was inaccurate, implying the critic did not care enough to pay attention. “I want to say that it is a terrible thing to be a black artist in this country,” he wrote, “for reasons too private to expose to the arrogance of white criticism.” Elsewhere, outside of the United States, Ganja & Hess played during International Critics’ Week at the Cannes Film Festival in 1973, where it reportedly received a standing ovation. “Because I am black,” Gunn continued to Weiler, “I do not even deserve the pride that one American feels for another when he discovers that a fellow countryman’s film has been selected as the only American film to be shown during Critic’s Week […] Not one white critic from any of the major newspapers even mentioned it.”

Gunn’s portrayal of sophisticated Black characters with money, taste, and intelligence resisted the stereotypes pervasive in studio filmmaking, so much so that they confronted U.S. critics who reviewed the film in 1973. “They had never seen a black millionaire in a mansion, with a limo and chauffeur,” said Schultz. The bad reviews led to poor box-office results, and the Playboy Theater turned the print over to the distributors after just three days. In a desperate attempt to recoup their investment, Kelly-Jordan Enterprises sold the rights to Heritage Enterprises, a grindhouse distributor that recut the 113-minute runtime down to 78 minutes, and then reissued Gunn’s work under the name Blood Couple, sometimes Double Possession. Fortunately, a single print of Gunn’s original version had been donated to the Museum of Modern Art, allowing for future restoration. Still, the episode left Gunn disenchanted with Hollywood, which at the time was supposedly experiencing a countercultural rebellion against traditional studio filmmaking. And yet, women and artists of color still had a difficult time breaking into the white establishment. Gunn later wrote about his experiences making the film in a play called Black Picture Show, where a Black screenwriter recalls his life in Hollywood from a mental institution. Gunn would not make another project until his final work, Personal Problems (1980), an improvisational drama shot independently and on video. Personal Problems never aired on public television as intended; like most of Gunn’s output as a director, it has been discovered after the fact.

Watching Ganja & Hess today, it’s apparent that Gunn had narrative and aesthetic preoccupations that have little in common with the work of Blaxploitation directors of the era. Therefore, it would have seemed strange and unusual next to Ossie Davis’ Cotton Comes to Harlem (1970), Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971), or Gordon Parks’ Shaft (1971) and Super Fly (1972). Playing in predominantly African American neighborhoods, these films received millions in box-office receipts for stories laden with crime, humor, and empowering messages geared toward their target audience. Blaxploitation became a niche that Hollywood would soon appropriate, resulting in sometimes harmful stereotypes that associate persons of color with criminal or violent behavior. Gunn’s work avoids those downfalls; his films prove reflective of Gunn himself as a well-educated, emotionally sensitive, and sexually exploratory human being. His artistic ambitions resisted the commercial packaging of Blaxploitation pictures, but he also didn’t believe in making films that catered to the pleas of Black community leaders who wanted positivity in African American cinema. Gunn told Impressions magazine after Ganja & Hess’ release, “I do it because I simply am black, I mean that’s the reality of my existence”—but Gunn avoided telling Black stories that perpetuated the representational tropes of Blaxploitation.

Though I have supplied a contextual framework by summarizing the story and providing some background on the film’s history, these descriptions of Ganja & Hess fail to adequately capture what a hypnotic, unconventional, and confronting film Gunn has made. It doesn’t resemble any other film in America at the time; rather, it seems to borrow from European filmmakers, with a blend of Michelangelo Antonioni’s alienation and Jean-Luc Godard’s formal experimentation. Its curious structure opens with white titles on a black screen, describing the basic story setup, and then it unfolds in three parts, each denoted by titles (Part I: Victim, Part II: Survival, etc.). This narrative composition is further framed by visual motifs with spellbinding patterns—discordant, dreamlike scenes of slow-motion show African tribespeople moving through Hess’ mind. Transitional dissolves take the viewer from Ganja or Hess into a piece of artwork, a combination of African and Western sculptures and paintings, and then back to our characters. The soundscape, too, proves other-worldly. Sam Waymon, Gunn’s friend and partner since the 1960s, composed the music. They would collaborate several times over the years and remain close until Gunn’s death in 1989. The film’s entrancing Bongili song, which pulsates onto the soundtrack whenever Hess feels an insatiable desire for blood, reverberates throughout. And late in the film, when Ganja kills her first victim, the delirious aural sequence includes two overlapping scores, a persistent deep hum, and the sounds of roaring animals—all to supremely disorienting effect.

Gunn said in interviews that Ganja & Hess is about addiction. Certainly, it would not be the last film to use vampires as a metaphor for drug addiction. After all, Luther, the minister who offers voiceover early in the film, describes Hess as a “victim” rather than a criminal for his addiction to blood. But there are also larger themes of identity at work, which suggest that Gunn’s interview responses were crafted. Sexuality accents much of the film, yet Gunn avoids portraying Black sexuality as carnal or primal, as many Hollywood and even Blaxploitation films did at the time. He presents Ganja and Hess as what scholar Marlo D. David calls “erotic subjects” free of Otherness. David also notes “a range of erotic emotions or tonalities—passion, seduction, desire, lust, possession, pleasure, and more—which invert, subvert, or otherwise transgress the conventional symbolic economy of the sexualized Other.” Gunn’s perspective on sexuality is marked by a receptiveness that opposes judgment. “Everybody’s some kind of freak,” Ganja tells Hess at one point, accepting of his tastes no matter what taboos they might break (she has a quick transition into vampirism). Gunn also creates a desire for a strong woman and an intelligent man of color in passionate scenes where the camerawork seems to lose itself in their bodies. Later, when Hess arranges for a young guest (Richard Harrow) for Ganja’s first victim, there’s a dinner scene where Hess watches unbothered as Ganja flirts with her prey. Ganja and the guest eventually make love, and Gunn shoots the sensuous rendezvous out of focus—and dusts their bodies with glitter to evoke beads of sweat flickering throughout the scene—to capture Ganja’s dueling, frenzied impulses of pleasure and bloodlust.

The theme of sexuality remains counter to the other major framework in Ganja & Hess, the Christian text that clashes with notions of open sexuality and the vampiric Mythrian yearning for blood. Luther’s presence marks the story with Christian morality, where Hess’ actions prove sinful and marred by shame. In their detailed analysis of the film, Manthia Diawara and Phyllis R. Klotman note how the most vital perspectives in the film, above all Ganja and Meda, exist in opposition to the Christian ideology of Luther and, in the end, Hess. “Rather than acknowledge the abundant life that Christ promises to those who come to Him and drink His ‘blood,’” they write, Hess “chooses human blood.” Thus, Hess’ interest in pagan African civilizations, sexual desire, and ultimately blood represent him straying from a Christian worldview. But Hess gravitates back to Christianity when he visits Luther and is absolved in the end. This allows him to expel the so-called evil in himself by standing in the shadow of a crucifix, once again accepting a Christian ideology, and dying with some measure of peace. And while Hess’ conclusion would seem to bring a certain moralizing shape to the film, Gunn’s last few moments identify with Ganja, who does not feel the same weight of Christian guilt that Hess does.

The last scene shows Ganja, a widow, returning to the lavish estate she now calls home. She looks out the window to see her first victim, the young dinner guest whom Ganja noted was still alive when she and Hess discarded his body in a field, returning from the dead. In the final glorious moment, he runs toward her, naked and alive. Ganja smiles, a knowing and contented expression. Throughout the film, Ganja remains an independent force accustomed to finding her own way. In one scene, she flatly admits to Hess that her main desire is “money,” and by the end, she has all Hess’ considerable wealth and independence, coupled with the liberation of immortality. Ganja is a woman of color who wants freedom, and she seems to resent conformity and subservience in any form. She prompts Hess with her direct, “rude” questions in their initial encounters and admits that she openly loathes decorum. Or note her antagonism toward Hess’ valet, Archie, a compliant and dutiful employee, who represents the sort of yielding that Ganja detests. In the end, as Diawara and Klotman observe, “She’s glad that Meda and Hess, the self-destructive artist and the bourgeois patriarch, are gone.” She is left “in command” and is pleased to experience complete control over her future for the first time. In this sense, Ganja & Hess is about Ganja more than Hess, as her name’s placement in the title indicates. In her essay “Whose Pussy Is This?” about Black sexuality, bell hooks writes about Ganja’s profound subjectivity as “the desiring blackwoman who prevails, who triumphs, not desexualized, not alone, who is ‘together’ in every sense of the word.”

Many of these themes were captured by Spike Lee, who called Gunn “one of the most under-appreciated filmmakers of his time,” when he brought renewed attention to Ganja & Hess by remaking the film in 2008. Lee’s version, called Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, and financed in part by a Kickstarter campaign, is exceptional for the way it takes a deeply personal work and applies a new set of personal signatures. But like much of Lee’s other films, his male gaze cannot be ignored, especially in his choice to alter Ganja’s undead lover from a male to a bisexual woman. Though gay, Gunn had relationships with women, and his perspective captured the beauty of human sexuality. Lee’s perspective is jealously heterosexual. Even so, his Ganja is a force to be reckoned with, played in a commanding performance by British actress Zaraah Abrahams. The difference between the two films remains that Gunn’s is a personal statement about identity and desire, whereas Lee delivers an inspired homage. For reasons I cannot adequately explain, the original has given me nightmares and seeped into my unconscious thoughts, whereas Lee’s version has drawn mere admiration for his skill and clear love of Gunn’s film. Regardless, Da Sweet Blood of Jesus continues to be one of Lee’s most unfairly dismissed works.

As for Ganja & Hess, Bill Gunn took the structure of a Dracula story and made an open-wounded statement that was brazenly uncommercial and intensely personal. Gunn’s critics sometimes faulted him for not being more direct in his politics, for not contributing more to the movement of African American filmmakers; however, his openness to individualism and desire is deeply revolutionary. “Philosophy is a prison,” says Gunn’s character Meda, an artist plagued with identity issues. “It disregards the uncustomary things about you.” Like Gunn, Meda rallies against various ideologies as a Black artist: the demands of both the white Hollywood mainstream and the organized movement of Black filmmakers; the weight of Christian guilt; the sexual boundaries of representation. Both Meda, and by extension, Gunn, were at odds with themselves and how the world views them. But while Ganja & Hess continues to haunt with its jarring imagery and aural schisms, it also inspires with its dissenting strain of individualism and self-actualization, captured in a remarkable piece of filmmaking.

Bibliography:

David, Marlo D. “‘Let It Go Black’: Desire and the Erotic Subject in the Films of Bill Gunn.” Black Camera, vol. 2, no. 2, 2011, pp. 26–46. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/blackcamera.2.2.26. Accessed 2 October 2020.

Diawara, Manthia, and Phyllis R. Klotman. “Ganja and Hess: Vampires, Sex, and Addictions.” Black American Literature Forum, vol. 25, no. 2, 1991, pp. 299–314. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3041688. Accessed 2 October 2020.

Gunn, Bill. “To Be a Black Artist.” 13 May 1973. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1973/05/13/archives/to-be-a-black-artist-a-black-artist-.html. Accessed 1 October 2020.

hooks, bell. Reel to Real: Race, Sex, and Class at the Movies. Routledge, 1996.

Monaco, James. American Film Now. Oxford University Press, 1979.

Ryfle, Steve. “The Eclipsed Visions of Bill Gunn: An African-American Auteur’s Elusive Genius, from Ganja & Hess to Personal Problems.” Cinéaste, vol. 43, no. 4, 2018, pp. 26–31. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26532844. Accessed 1 October 2020.

Walker, David, and Tim Lucas. “Ganja and Hess: The Savaging and Salvaging of an American Classic.” Video Watchdog. No. 3, Jan/Feb, 1991, pp. 38-57.

Weiler, A.H. “Screen: Gunn’s ‘Ganja & Hess’ Opens.” 21 April 1973. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1973/04/21/archives/screen-gunns-ganja-hess-opensthe-cast.html. Accessed 1 October 2020.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review