The Definitives

The Celebration

Essay by Brian Eggert |

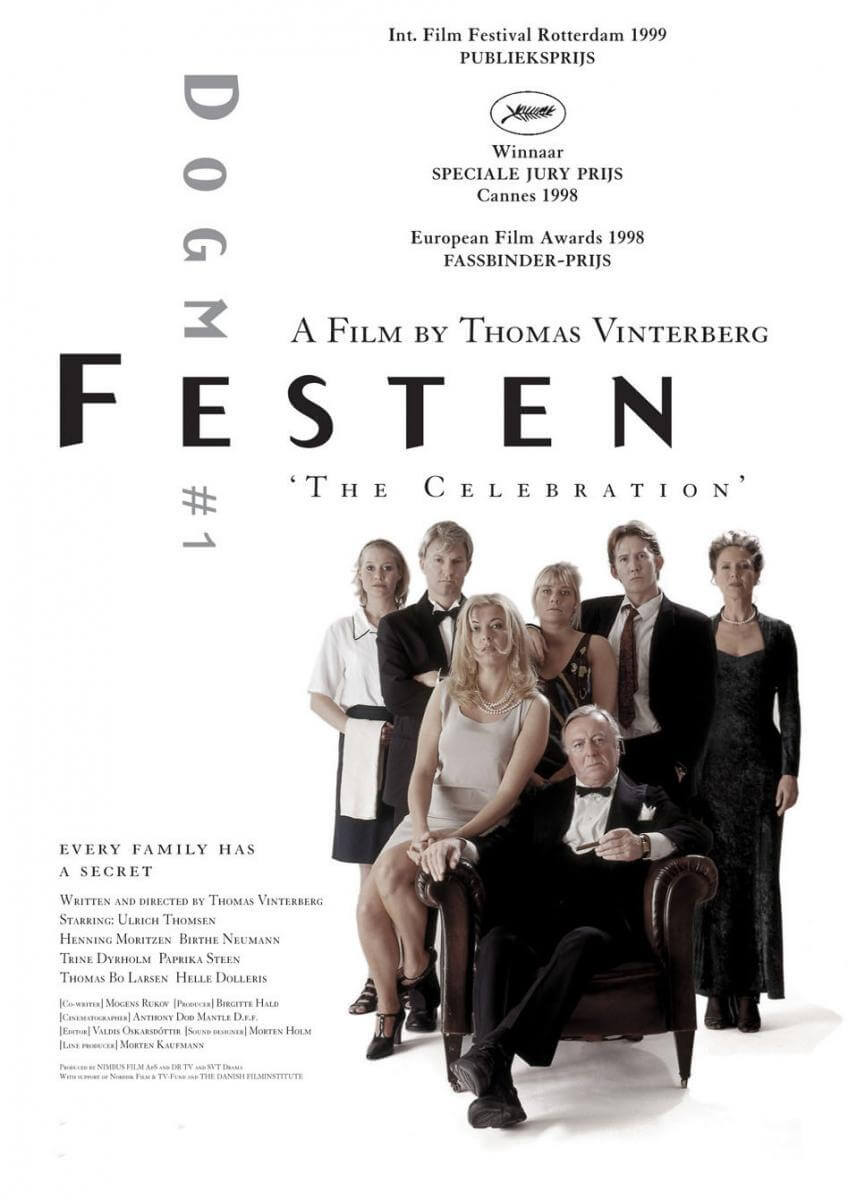

In The Celebration (Festen), the camera explores and invades personal spaces like someone shooting a home movie at a birthday party. The 1998 film was among the earliest to use a handheld digital video camera, and the stimulating effect exposes ugly truths about its characters. The technical choice was compelled out of practical and artistic disciplines passed down by Dogme 95, an experiment by Danish provocateurs who questioned conventional forms of cinema, narrative tropes, and compositional norms. Under the film’s Dogme 95 banner (its official title is Dogme #1: Festen), it remains inextricable from the movement and its strictures, which gave the uncredited director, Thomas Vinterberg, the boundaries in which he devised and completed the production. The result strips away artifice in both technique and content, reflecting Dogme 95 principles better than any other because its narrative presents an apt analogy to the movement’s views. Vinterberg’s alignment of narrative and the form prescribed by Dogme 95 creates an intellectually satisfying organization of visual and thematic contexts. But the film endures beyond its significance in film history and experimental cinema. Its portrait of paternalism, the fallacy of benign patriarchal entitlement, Danish racism, and the taboos of incest and pedophilia strike the viewer like a slap in the face. Although it’s a multifaceted film with layers that welcome examination, it’s also a work that moves the viewer with its unfiltered truth.

The Celebration unfolds over the 24 hours surrounding the sixtieth birthday dinner of Helge Klingenfeldt-Hansen (Henning Moritzen), a respected businessman. Family and friends gather at the Klingenfeldt-Hansen lodge, the family’s elaborate hotel. Along with Helge’s devoted wife Else (Birthe Neumann), Helge is joined by his eldest son, the moody and preoccupied Christian (Ulrich Thomsen); his loner daughter, Helene (Paprika Steen); and his volatile son, Michael (Thomas Bo Larsen), accompanied by his wife and two children. Two dozen guests from Helge’s inner circle arrive, and the evening’s toastmaster Helmuth (Klaus Bondam) begins the party with an exalting speech. The scene appears cheery and idyllic, despite the recent suicide of Christian’s twin sister, Linda. Then, Christian interrupts the formal banquet of tuxedos and fine cuisine to toast his father, confessing before all that he and Linda were victims of their father’s sexual abuse throughout their childhood. However shocking this revelation, the admission causes only a brief interruption in the oppressive air of ritualized formality and respectability. One guest claps. Else offers an uncomfortable smile. Gradually, the evening brings damning speeches, a vile song, and violent outbursts. All the while, the unimpedable etiquette strips away the façades, leaving only a grotesque portrait of the bourgeoisie and its figurehead—an incestuous patriarch.

Vinterberg’s film marks the first entry in the Dogme 95 movement. Formed under Lars Von Trier and Vinterberg, along with “brethren” Christian Levring and Søren Kragh-Jacobsen, Dogme 95 was unleashed onto the world like Christian’s speech in The Celebration—a blow to the establishment conveyed in a public space. On March 20, 1995, Von Trier was scheduled to appear at the Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe in Paris for a symposium on the state of cinema after 100 years. France’s Ministry of Culture arranged the formal affair, which boasted a prominent guest list decked out in tuxedos and evening gowns. Von Trier’s talk was just two days short of the 100th anniversary of the Lumière brothers showing their first film to a small audience at the Grand Café in Paris in 1895. Von Trier took the podium, wearing a plaid flannel shirt that contrasted the evening’s attire, and read what he called the “Dogme 95 Manifesto” and its “Vow of Chastity” aloud before tossing copies of the manifesto, printed on red paper, to the audience below. Von Trier left without taking questions.

The Dogme 95 movement sought to counteract the predominance of globalization, illusion, escapism, individualism, and mindless spectacle perpetuated mainly by Hollywood. Vinterberg called it “a reaction to the laziness and mediocrity in both European and American cinema.” Its Vow establishes a set of ten procedures, or commandments, that filmmakers must follow to capture and replicate reality. The commandments function to remove the layers of production between the performers and the audience, the artificial lighting or musical score during scenes that fabricate emotion and “dress” a film, to achieve a realistic alternative—what Vinterberg aspirationally calls a “naked film.” The approach lays bare the story and actors, which are the “raw material” of film. But these ideas were not unprecedented, and some critics sneered at the notion that Von Trier and Vinterberg were creating anything new. After all, filmmakers like Vittorio De Sica, François Truffaut, and John Cassavetes tried similar tactics to achieve something more realistic and authentic. Moreover, the rule-bound nature of filmmaking under Von Trier and Vinterberg’s manifesto allows for variation, resulting in wildly different examples within the thirty or so films made under the movement’s banner since the 1995 declaration, as each filmmaker interprets Dogme 95’s guidelines differently.

The Dogme 95 movement sought to counteract the predominance of globalization, illusion, escapism, individualism, and mindless spectacle perpetuated mainly by Hollywood. Vinterberg called it “a reaction to the laziness and mediocrity in both European and American cinema.” Its Vow establishes a set of ten procedures, or commandments, that filmmakers must follow to capture and replicate reality. The commandments function to remove the layers of production between the performers and the audience, the artificial lighting or musical score during scenes that fabricate emotion and “dress” a film, to achieve a realistic alternative—what Vinterberg aspirationally calls a “naked film.” The approach lays bare the story and actors, which are the “raw material” of film. But these ideas were not unprecedented, and some critics sneered at the notion that Von Trier and Vinterberg were creating anything new. After all, filmmakers like Vittorio De Sica, François Truffaut, and John Cassavetes tried similar tactics to achieve something more realistic and authentic. Moreover, the rule-bound nature of filmmaking under Von Trier and Vinterberg’s manifesto allows for variation, resulting in wildly different examples within the thirty or so films made under the movement’s banner since the 1995 declaration, as each filmmaker interprets Dogme 95’s guidelines differently.

The “Vow of Chastity” signed by Vinterberg and Von Trier stipulates the limitations that will circumscribe, and in another way, inspire filmmakers to create something real. They sought to “force the truth out” of characters and settings “by all the means available and at the cost of any good taste and any aesthetic considerations.” The limitations include location shooting without the luxury of studio props, post-synchronized sound, or non-diegetic sound. The cinematographer must shoot in color and the boxy Academy aspect ratio, using only handheld cameras, and no special lighting or filters to alter the image. Although the vow does not specify the nature of truth that the filmmaker should explore, there are some representational limits. For instance, the film cannot explore truth through genre exercises, nor can the film employ “superficial action” such as murders or weapons. In addition, the film must take place “here and now” and avoid expressive uses of “temporal and geographical isolation.” And finally, the director must go uncredited—a rule meant to deflate the artistic impetus of filmmaking and commit the director to the film’s raison d’être: revealing truth.

Their movement hoped to “start a wave in all humility,” according to Vinterberg. The wave he refers to comes from similar artistic principles found in various neo-realist movements (Italian, Brazillian, et al.) and, most famously, the French New Wave. In the late 1950s, French directors sought to rally against the “Tradition of Quality” in French cinema. Dogme 95 had a similar impetus. The manifesto’s first sentence mentions “the expressed goal of countering ‘certain tendencies’ in the cinema today,” a pointed nod to François Truffaut’s article “A Certain Tendency of French Cinema” in a 1954 issue of the Cahiers du Cinéma, which is often called the French New Wave’s manifesto. In an early interview about Dogme 95 and The Celebration before its release at Cannes, Vinterberg explained how Danish film had its own bad habits that produced a standard kind of film. “When a film director makes a film, it quite automatically gets done in a particular way. You have a unit of thirty people around you, lots of lighting and all that, which has to be planned ages in advance. It’s a large, ponderous machine.” The production process had become so standardized that films could not help but turn out a certain way. “So 1995 was an obvious time to try and shake oneself out of all that in some way, and explore what can actually be done with the really basic qualities in film,” said Vinterberg. And if the markedly anti-bourgeoisie Dogme 95 movement identified production standards, many of them established by Hollywood cinema, as the conservative tradition, then the Klingenfeldt-Hansen family circle, so dependent on respectable manners and preserving conventions, is The Celebration’s narrative equivalent.

Note how there’s no mention of politics or morality in the Dogme 95 rules. It’s not a manifesto of ideological causes, except to counter the cinematic establishment. The Celebration carries forth this notion when Christian’s speech creates a division between his father’s establishment and those on its margins—the underclass and outsiders. After Christian makes his initial announcement, members of the family attempt to control the situation by redirecting attention and rejecting his claims as a morbid joke. Helge feins confusion at first. Helene apologizes for the speech and assures the guests his accusations are false. Else insists Christian has a knack for fiction and could be an author. Group denial takes over as the guests continue with their dinner. Others stand to give speeches and sing songs in Helge’s honor. Christian resolves to leave the party, but Kim (Bjarne Henriksen), a longtime friend and the hotel’s chef, stops him. Aware of Helge’s crimes, Kim tells Christian to return to his seat and finish what he started. At the same time, Kim orders the hotel staff to enter the guests’ rooms and take their car keys so no one can flee the truth. When Christian returns to the party, he gives a second speech and claims Helge is responsible for Linda’s death (“Here’s to the man who murdered my sister.”). The denials become more forceful. Helge’s defenders grow angry with Christian, who is labeled “sick and disturbed.” Helmuth calls for a break, and many guests consider leaving but find their car keys are missing. The Celebration becomes an upstairs-downstairs drama. The servant class removes the ruling class’s power by aiding Christian in destabilizing his father’s patriarchal position and the hypocrisy of those who support him. The Dogme 95 movement sought to achieve something similar, positioning itself in the role of usurper.

Note how there’s no mention of politics or morality in the Dogme 95 rules. It’s not a manifesto of ideological causes, except to counter the cinematic establishment. The Celebration carries forth this notion when Christian’s speech creates a division between his father’s establishment and those on its margins—the underclass and outsiders. After Christian makes his initial announcement, members of the family attempt to control the situation by redirecting attention and rejecting his claims as a morbid joke. Helge feins confusion at first. Helene apologizes for the speech and assures the guests his accusations are false. Else insists Christian has a knack for fiction and could be an author. Group denial takes over as the guests continue with their dinner. Others stand to give speeches and sing songs in Helge’s honor. Christian resolves to leave the party, but Kim (Bjarne Henriksen), a longtime friend and the hotel’s chef, stops him. Aware of Helge’s crimes, Kim tells Christian to return to his seat and finish what he started. At the same time, Kim orders the hotel staff to enter the guests’ rooms and take their car keys so no one can flee the truth. When Christian returns to the party, he gives a second speech and claims Helge is responsible for Linda’s death (“Here’s to the man who murdered my sister.”). The denials become more forceful. Helge’s defenders grow angry with Christian, who is labeled “sick and disturbed.” Helmuth calls for a break, and many guests consider leaving but find their car keys are missing. The Celebration becomes an upstairs-downstairs drama. The servant class removes the ruling class’s power by aiding Christian in destabilizing his father’s patriarchal position and the hypocrisy of those who support him. The Dogme 95 movement sought to achieve something similar, positioning itself in the role of usurper.

Many detractors buckled against the hype around Dogme 95 since few of the filmmakers involved could be called modest or reticent about self-promotion—and the line between art and ego is almost always nonexistent. Even though the manifesto treats the director with ambivalence—it states, “The director must not be credited,” and must “refrain from personal taste”—it’s impossible not to consider Vinterberg himself. His openness and energy about Dogme 95 made him the focus of press coverage after The Celebration’s release (journalist Maria Mackinney called Vinterberg the “golden boy and heartthrob of Danish cinema”). The Celebration was only Vinterberg’s second feature after The Biggest Heroes (1996) and several short films. At 25, he was nominated for an Oscar for his graduate film, Last Round (1994). But his early successes continued to mark his subsequent films with an air of disappointment. He dabbled in commercially minded products in the years to follow, from a traditional costume drama (Far from the Madding Crowd, 2015) to a based-on-real-life submarine thriller (Kursk, 2018). Still, he remains attracted to stories that proceed blithely yet have an undeniably dark undercurrent, often about middle-class conformity in which the heroes are misfits and outsiders. Film commentators continue to draw comparisons between Vinterberg’s later work and his early masterpiece—above all The Hunt (2012), about a man wrongly accused of sexual misconduct with a minor, and Another Round (2020), his Oscar-winner for Best International Film, about a group of friends who experiment with daily alcohol consumption to improve their social and professional lives.

Unlike Von Trier, who used Dogme 95 as controlled and intentional experimentation in another of his long line of future provocations, Vinterberg’s use of the rules proves more intuitive in The Celebration. He uses Dogme 95 to unify technique and narrative, allowing the rules to drive the story. He based the film on an account first shared by a man known only as “Allan,” who appeared on a Danish radio program called Koplev’s Crossword. Allan claimed to have called out his father’s sexual abuse at a family dinner. Vinterberg and co-writer Mogens Rukov drew from that story, which Allan fabricated as investigative journalists learned sometime later. Even so, the idea supplied the catalyst for the screen story, which grew out of Dogme 95’s call for purity in the playful spirit of inspiration through limitation. For instance, the Manifesto’s stricture demanding actual locations inspired Vinterberg to shoot inside a hotel for practical ease. Filming over six weeks at Skjoldenæsholm Castle, a manor house in Ringsted, allowed for a single location in which the cast and crew could move about freely. The hotel setting inspired Vinterberg to create scenes with multiple guests in their rooms, a receptionist character, and the kitchen staff. Following such restrictions, he was able to complete the script in a week. In interviews at the time, Vinterberg repeatedly called shooting The Celebration, “actually the most liberating project” and “the most enjoyable project I’ve ever been involved in.”

Dogme 95 also established several technical limitations for The Celebration, which guided how the film looks and sounds. The Manifesto’s rules dictate that the film could not separate sound and image, creating challenges for British cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle. His kinetic style would later give Danny Boyle a signature look on films like 28 Days Later (2002) and Slumdog Millionaire (2009)—the latter earned Mantle an Oscar for Best Cinematography. Mantle studied alongside Vinterberg and other Dogme 95 signees at the National Film School of Denmark. He shot many of the movement’s early films, including Søren Kragh-Jacobsen’s Mifune’s Last Song (1999) and Harmone Korine’s loosely adherent Julien Donkey-Boy (1999). For The Celebration, Mantle shoots with a handheld Sony PC7 E, using Mini-DV cassettes and an array of active movements to capture the film’s distinct and thematically fitting home movie look. The style evokes Vinterberg’s portrait of moral frenzy through the performers’ somewhat improvisational acting style. And since the director allowed the actors to dictate the gestures of a scene, Mantle’s camera relays their physical reality and movements by following them closely. “The camera is embedded, and by extension embodied, in a space full of human life,” noted author C. Claire Thomson. Take Mantle’s extreme close-ups and wide-angle lenses, which place the viewer in the physical environment as both participant and spectator. Of course, shooting with handheld or seemingly disordered camerawork was not a new conceit in 1998. Vinterberg’s film isn’t a work of aesthetic revolution. However, Dogme 95’s constraints provided a framework for a uniquely powerful unification of style and subject matter, and its searing emotional content prevents the film from becoming a mere exercise in technique.

Dogme 95 also established several technical limitations for The Celebration, which guided how the film looks and sounds. The Manifesto’s rules dictate that the film could not separate sound and image, creating challenges for British cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle. His kinetic style would later give Danny Boyle a signature look on films like 28 Days Later (2002) and Slumdog Millionaire (2009)—the latter earned Mantle an Oscar for Best Cinematography. Mantle studied alongside Vinterberg and other Dogme 95 signees at the National Film School of Denmark. He shot many of the movement’s early films, including Søren Kragh-Jacobsen’s Mifune’s Last Song (1999) and Harmone Korine’s loosely adherent Julien Donkey-Boy (1999). For The Celebration, Mantle shoots with a handheld Sony PC7 E, using Mini-DV cassettes and an array of active movements to capture the film’s distinct and thematically fitting home movie look. The style evokes Vinterberg’s portrait of moral frenzy through the performers’ somewhat improvisational acting style. And since the director allowed the actors to dictate the gestures of a scene, Mantle’s camera relays their physical reality and movements by following them closely. “The camera is embedded, and by extension embodied, in a space full of human life,” noted author C. Claire Thomson. Take Mantle’s extreme close-ups and wide-angle lenses, which place the viewer in the physical environment as both participant and spectator. Of course, shooting with handheld or seemingly disordered camerawork was not a new conceit in 1998. Vinterberg’s film isn’t a work of aesthetic revolution. However, Dogme 95’s constraints provided a framework for a uniquely powerful unification of style and subject matter, and its searing emotional content prevents the film from becoming a mere exercise in technique.

Despite its status as the first Dogma 95 offering, The Celebration betrays the “Vow of Chastity” in certain flourishes. Although the rules strictly forbid genre films, Linda, Christian’s twin sister who committed suicide, haunts the hotel in ghost form. Vinterberg uses a literal ghost to echo the past—the return of the repressed or oppressed. Undoubtedly the presence of a spirit, whether real or imagined, constitutes an artificial mode of action or even genre flourish. Even so, the ghostly impetus leads to a moment of visceral truth. Early in the film, Helene finds herself assigned to Linda’s former room. When they were children, they played a game called “You’re Getting Warmer,” where Linda left clues to a hidden object. Helene plays their secret childhood game once more and finds Linda’s suicide note. She reads the letter and, in a stroke of compartmentalization, hides it inside her toiletry bag. Later in the evening, Pia (Trine Dyrholm), a member of the hotel’s staff who’s having a romance with Christian, arranges for Helene to read the note in front of the guests. The note’s contents cannot be denied, and it’s the moment that finally turns many in the anti-Christian crowd into believers. Just like his sister, Christian is a kind of ghost, returning to haunt the living when he calls out Helge, Else, and any “hypocritical and corrupt” guests who knew about the abuse and did nothing. When Christian finally achieves some measure of catharsis, Linda appears to him in a dream and says goodbye. And while this narrative conceit tiptoes into genre, it helps, as the Vow of Chastity demands, “force the truth out of my characters and settings.”

Regardless of its debatable breaches of Dogme 95’s commandments, Vinterberg’s film would go on to win the Jury Prize at Cannes. The director noted that the audience at Cannes responded “with a deep, deep silence and darkness.” In earlier preview screenings in Copenhagen, he reported that some viewers fainted or left the theater, only to come back and find out what happened. “Then they [would] phone me two days later, still in the throes of the film, and tell me how fantastic they think it is.” American audiences, he noted, tended to respond with uncomfortable laughter, while American critics described the film in terms of a “raw black comedy,” as stated in Film Comment. But Vinterberg insists on the film’s dramatic roots, even if he often uses humor to disarm. He told Cinéaste that “people open up when they laugh. Since they open up, they’re ready to receive another kick in the face. If it’s black all the way, within fifteen minutes there’ll be a fence between the audience and the film.” The Celebration went on to win the New York Critics Circle and Los Angeles Critics Association awards for Best Foreign Language Film, along with prizes in every major category in the Robert Awards, the Danish equivalent of the Oscars. And given the film’s single setting and universal portrait of class and family dynamics, it has been adapted to the stage in several countries as well.

Beyond Dogme 95, The Celebration remains an essential film for its portrait of a bourgeoisie family and the gradual and unnerving way it penetrates and peels away the surface to reveal the truth. The child abuse in Christian’s speeches and Linda’s suicide note is not the subject of The Celebration; it merely ignites the spark that lights this family ablaze, burning away the veneer to uncover the family’s corrupted foundation. Vinterberg admitted, “I have penetrated a layer of evil and abomination I’d never been to before.” To be sure, the abuses themselves feel less shocking than how the party’s guests respond after hearing the accusations. Even after Helene reads Linda’s suicide note aloud, which eliminates any doubt of Helge’s innocence, the German toastmaster resumes the festivities with coffee and dancing. The film’s subject seems to be the extent to which people will go to preserve corrupt power structures, whereas the themes of child abuse and racism remain universal in families that never investigate what’s behind their proper front. Vinterberg believes this points to the rise of fascism. “Maybe the reason for fascism growing stronger throughout Europe can be found in the family structure,” he told Cinéaste in 1999. Families rooted in paternalism and an autocratic father reinforce obedient power structures that allow abusive, unhealthy authoritarian leaders such as Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, and Xi Jinping to emerge.

Beyond Dogme 95, The Celebration remains an essential film for its portrait of a bourgeoisie family and the gradual and unnerving way it penetrates and peels away the surface to reveal the truth. The child abuse in Christian’s speeches and Linda’s suicide note is not the subject of The Celebration; it merely ignites the spark that lights this family ablaze, burning away the veneer to uncover the family’s corrupted foundation. Vinterberg admitted, “I have penetrated a layer of evil and abomination I’d never been to before.” To be sure, the abuses themselves feel less shocking than how the party’s guests respond after hearing the accusations. Even after Helene reads Linda’s suicide note aloud, which eliminates any doubt of Helge’s innocence, the German toastmaster resumes the festivities with coffee and dancing. The film’s subject seems to be the extent to which people will go to preserve corrupt power structures, whereas the themes of child abuse and racism remain universal in families that never investigate what’s behind their proper front. Vinterberg believes this points to the rise of fascism. “Maybe the reason for fascism growing stronger throughout Europe can be found in the family structure,” he told Cinéaste in 1999. Families rooted in paternalism and an autocratic father reinforce obedient power structures that allow abusive, unhealthy authoritarian leaders such as Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, and Xi Jinping to emerge.

The paternalist theme is best shown in Michael, who starts as the family’s black sheep yet so desperately wants his father’s approval and the power that comes with it. He wasn’t invited to the party after drinking too much and making a scene the year before. But when Michael shows up, Helge resolves, “I suppose I’ll have to talk to him.” Michael is aware of his failings, but he cannot help himself; he’s a philanderer, alcoholic, abuser of women, and outspoken racist. Still, there’s a sadness to him that makes him vulnerable and tragic in his desperate need for his father’s approval, regardless of his unhinged and hilariously childish temperament. When Helge asks him to ensure the party runs smoothly, hinting that Michael may be a candidate to join the secretive Freemasons, Michael puffs out his chest and, in his brown shoes that don’t match his tuxedo, acts like a big shot. Following his father’s orders and maintaining the party’s integrity means, when Christian makes his third and most aggressive speech (“I’m sorry that you’re all such cunts”), Michael responds with extreme prejudice—he and two other men take Christian outside, beat him, and tie him to a tree in the woods. Only later, after Helene reads Linda’s suicide note, and the party turns against Helge, who, in his deflated state can no longer issue Michael power, does Michael align with his siblings and turn on his father. In the middle of the night, Michael attacks Helge, throws him to the ground, and prepares to urinate on his father before Christian stops him.

Vinterberg’s film is so compelling because his early scenes portray an outwardly traditional, doggedly patriarchal, family dynamic. The relationships between siblings, the father and his children, prove familiar—if ornamented with Klingenfeldt-Hansen privilege. The first half-hour shows Helge as a likable, stately father with a sense of humor. Christian, ever the sullen outsider, walks to the hotel from the bus depot. Michael, erratic and impulsive, drives past him, only to slam on the brakes, kick his wife and their children out of the car, and transport Christian to the hotel—making his family walk the remaining distance in a comically cruel act. Helene prepares for the party by smoking pot in the taxi. Vinterberg and editor Valdís Óskarsdóttir draw almost supernatural parallels between these siblings in a sequence that cross-cuts between them: Helene finds Linda’s suicide note and begins to cry; in another room, Michael slips and falls in the shower, pathetically blaming his wife for leaving the soap out; in yet another room, Christian passes out, while in his bathtub, something unexplained startles Pia. Cutting between the three rooms, Vinterberg creates a sharply edited and abrupt sequence that reveals an ethereal connection between the siblings, their stark differences notwithstanding.

A blend of the familiar and seditious, The Celebration takes a classical narrative treatment and strains it through Dogme 95’s filter to produce a mixture of traditional and avant-garde. It follows an archetypal dramatic structure reminiscent of Oedipus at Colonus, while the story of a Danish son prompted by a ghostly presence to reconsider his father’s legacy and family’s good name comes straight out of Hamlet. But the subject of incest combined with the formal techniques and handheld camerawork turns the film into a conversation between the traditional and the postmodern. These revisions apply to cinema as well. Vinterberg admits to “plagiarism” of Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander (1982) for the sequence involving a chain of dancers throughout the house. Though Bergman’s film uses a similar dance to portray the joyful Christmas celebrations at the family’s peak of happiness, Vinterberg twists the dance into a horrific display whose inappropriate merriment comes after Christian’s speeches. Vinterberg also based Christian and Michael on Al Pacino and James Caan’s characters in The Godfather (1972), using what have become classical archetypes in new contexts. Also, casting Henning Moritzen as the patriarch—who defends raping his children with the devastating line, “It was all you were good for”—is a statement in itself. Moritzen, an esteemed veteran of Danish cinema, projected respectability over his forty-year career. Afterward, the actor found it difficult to shake the fictional associations between himself and Helge.

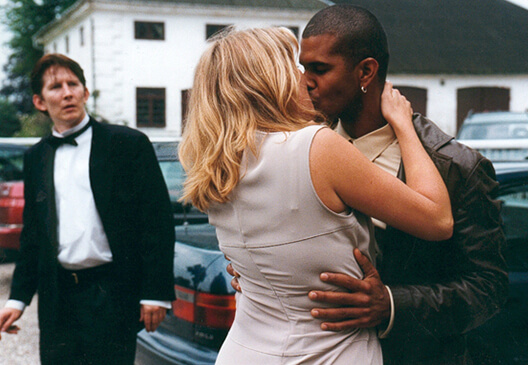

The film’s elaborate festivities recall the opening wedding sequences in The Godfather or The Deer Hunter (1978), except Vinterberg reveals the warped quality of the guests in a commentary on Danish society. Late to the party is Helene’s boyfriend, Gbotakai (Gbatokai Dakinah), a Black man from America. Immediately upon Gbotakai’s arrival, Michael, dutifully playing watchdog according to his father’s orders, treats him like a servant or musician and calls him “Charlie Brown” and a “monkey.” Helene embraces her boyfriend, and Michael’s reaction is disturbingly unguarded. Later that evening, Gbotakai defiantly taunts Michael by toasting “to your brother,” thus aligning himself on Christian’s side of the family conflict. Michael responds by leading the party in “a little sing-along”—he bellows the Danish children’s song “Jeg har set en rigtig negermand” (“I have seen a real negro man”), the lyrics of which use a series of crude similes to describe non-white races. The guests join in, directing their performance at Gbotakai, who does not understand. Helene explains that it’s “a racist song.” Vinterberg renders the singers’ grotesque, drunken, enthusiastic faces—like something out of the “Hail, Satan!” finale of Rosemary’s Baby (1968)—taking perverse pleasure in singing their racist children’s song. The film’s portrait of a family institution marked by incest, pedophilia, and racism raises questions about why culture holds traditionalism so dear. It is perhaps the most fitting theme of any Dogme 95 film.

The film’s elaborate festivities recall the opening wedding sequences in The Godfather or The Deer Hunter (1978), except Vinterberg reveals the warped quality of the guests in a commentary on Danish society. Late to the party is Helene’s boyfriend, Gbotakai (Gbatokai Dakinah), a Black man from America. Immediately upon Gbotakai’s arrival, Michael, dutifully playing watchdog according to his father’s orders, treats him like a servant or musician and calls him “Charlie Brown” and a “monkey.” Helene embraces her boyfriend, and Michael’s reaction is disturbingly unguarded. Later that evening, Gbotakai defiantly taunts Michael by toasting “to your brother,” thus aligning himself on Christian’s side of the family conflict. Michael responds by leading the party in “a little sing-along”—he bellows the Danish children’s song “Jeg har set en rigtig negermand” (“I have seen a real negro man”), the lyrics of which use a series of crude similes to describe non-white races. The guests join in, directing their performance at Gbotakai, who does not understand. Helene explains that it’s “a racist song.” Vinterberg renders the singers’ grotesque, drunken, enthusiastic faces—like something out of the “Hail, Satan!” finale of Rosemary’s Baby (1968)—taking perverse pleasure in singing their racist children’s song. The film’s portrait of a family institution marked by incest, pedophilia, and racism raises questions about why culture holds traditionalism so dear. It is perhaps the most fitting theme of any Dogme 95 film.

Some have accused Dogme 95 of being a tool for self-promotion, specifically for Von Trier, given how short-lived the movement was and how much attention it brought him in the subsequent years. Dogme 95 might even be called a publicity stunt, except it resulted in several notable films worldwide that earned an official certificate. Vinterberg made only one film that adheres to the Dogme 95 limitations, and it’s arguably the most emotionally and technically effective for how it encapsulates the movement’s anti-traditionalist worldview within a narrative. Of course, The Celebration, and many other Dogme 95 examples, cannot help but betray several rules in the Vow of Chastity. Although Vinterberg admits they set out “to be as un-auteur-like as possible,” he concedes that, “Funnily enough, the result is some pretty auteur-like films.” If the interviews quoted throughout this essay are any indication, Vinterberg gladly participated in the film’s promotion, identifying himself as director, even if the credits do not (he also appears in a cameo as Gbotakai’s taxi driver). The strict rules of Dogme 95 aside, the movement has an ironic understanding of the interplay between conventional and unconventional modes. The evident coaction becomes clear the next morning after the party, when the family resumes its civility over breakfast, as though their world hadn’t shattered the prior evening. But Helge will have to atone. Michael asks his father to leave the table “so we can eat our breakfast.” Vindicated, Christian finds peace with Linda during a dream, leaving him to pursue a relationship with Pia, a woman to whom he could never commit given his traumatized state. It’s a rare moment of catharsis and hope—even a happy ending—for such a bleak film.

While it’s tempting to lose oneself in the lasting critical and historical significance of Dogme 95’s anti-commercialism and experimentally vibrant consequence, the movement itself stalled long ago, in the early 2000s. The Celebration transcends the movement, even while its narrative exists in symbolic, dramatic harmony with Dogme 95’s attitude toward cinematic conventions. Today, Vinterberg’s film remains one of the most influential Scandinavian films of all time for introducing the world to the movement’s familiar innovations and home movie aesthetic. Its popularity and critical acclaim helped establish digital filmmaking so independent and small-scale productions could explore inexpensive handheld cameras as a means of experimentation and cost reduction. However, its lasting and relevant remarks about patriarchal power and abuses of authority, the sheer gut-punch quality of the story, and its barbed humor continue to affect viewers. The contexts involving Dogme 95, the controversy around its illegitimate origins, and its place in film history enrich, and even threaten to overshadow, the considerable degree of feeling and participation the film conjures through its structure and narrative. It’s an unforgettable film enriched by layers of interpretation; however, its power rests not in intellectual contexts but in the emotionally draining and intense experience it creates.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your suggestion and support, Per!)

Bibliography

Hjort, Mette, and Scott MacKenzie (Editors). Purity and Provocation: Dogme 95. British Film Institute, 2003. Jensen, Bo Green. “Interview.” April 1998. http://www.dogme95.dk/celebration/. Accessed 30 August 2021.

Mackinney, Maria. “Thomas Vinterberg.” BOMB, Winter, 1999, No. 66 (Winter, 1999), pp. 56-61. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40425915. Accessed 30 August 2021.

Porton, Robert. “Something Rotten in the State of Denmark: An Interview with Thomas Vinterberg.” Cinéaste, 1999, Vol. 24, No. 2/3, pp. 17-19. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41689136. Accessed 30 August 2021.

Simons, Jan. “Playing the Waves: The Name of the Game is Dogme95.” Cinephilia: Movies, Love and Memory, edited by Marijke De Valck and Malte Hagener, Amsterdam University Press, 2005, pp. 181–196.

—. “Von Trier’s Cinematic Games.” Journal of Film and Video, vol. 60, no. 1, 2008, pp. 3–13. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20688581. Accessed 30 August 2021.

Stevenson, Jack. Dogma Uncut: Lars von Trier, Thomas Vinterberg, and the Gang That Took on Hollywood. Santa Monica Press, 2003.

Thomson, C. Claire. Thomas Vinterberg’s Festen (The Celebration). Nordic Film Classics. University of Washington Press, 2013.

Weber, Miles. “Cowboys and Idiots.” New England Review, Summer, 2004, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 190-196. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40244443. Accessed 30 August 2021.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review