The Definitives

Critical essays, histories, and appreciations of great films

Caché

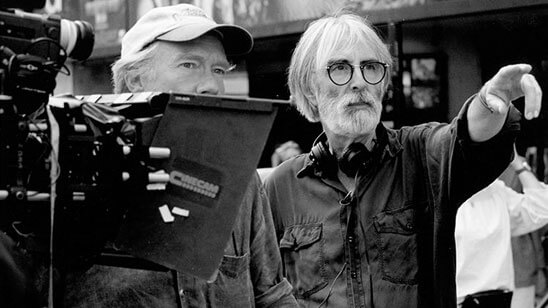

- Director

- Michael Haneke

- Cast

- Juliette Binoche, Daniel Auteuil, Maurice Bénichou, Lester Makedonsky, Walid Afkir, Annie Giradot, Daniel Duval, Nathalie Richard, Bernard Le Coq, Denis Podalydès

- Rated

- R

- Runtime

- 109 min.

- Release Date

- 10/05/2005

In Michael Haneke’s Caché, Georges and Anne Laurent host a dinner party where their friend, Yvon, describes his recent encounter with a curious elderly woman. The woman claimed her dog was hit by a van on the very same day, even the same moment, of Yvon’s birth. Is Yvon the reincarnation of this woman’s dog? How could he ever know? But he cannot stop from guiding Anne’s hand to the back of his neck, where there’s a curious scar in the same place where the dog was struck by the van’s bumper. All at once, Yvon barks and startles the entire table of guests. Many of the guests laugh at Yvon’s story, assuming it was a joke. One of them asks, “Is it true or not?” Everyone laughs again, but this time somewhat uncertainly so. Rather than confirm whether his story was true, Yvon asks, “You don’t believe me?” But the point of Yvon’s story was not the truth of the matter; it was what the story produced: the payoff of laughter, the certainty among some that Yvon’s account was merely an elaborate joke, and the lingering potential that some part of his story was true. The message of this scene, and perhaps the entire film, cannot be answered with a single question, such as whether the most obvious aspect of the story was true. Rather, its purpose resides in the acknowledgment of its uncertainty, in how that uncertainty is achieved, and in appreciation of the bounty in Haneke’s filmmaking.

The lingering question in Caché, released in 2005, concerns the origin of mysterious videotapes left at the door of Georges and Anne’s Parisian home. The initial VHS tapes are stationary recordings of the Laurent home exterior. Georges, played by Daniel Auteuil, hosts a literary talk show for public television and, at first, believes the tapes may have come from a troubled viewer. Anne, played by Juliette Binoche, feels less certain and more unnerved by the tapes, which, as more arrive, become increasingly invasive and disturbing—some of them wrapped in crude child’s drawings that depict stark, bloody scenes. As more tapes arrive, Georges seems to know about them, though he’s reluctant to speak about what he knows. He believes an Algerian man named Majid (Maurice Bénichou), who was once a childhood friend and nearly his adopted brother, may be responsible. However, after being confronted by Georges and accused of sending the tapes, Majid kills himself. In the film’s closing shot, another stationary image like those on the videotapes, this one positioned outside of a school, the observant viewer will spy the Laurents’ 12-year-old son, Pierrot (Lester Makedonsky), speaking with Majid’s unnamed son (Walid Afkir), a young man in his late teens. But these two boys should not know one another, as no information from earlier in the film suggests they would have ever met.

This final, four-minute shot in which Pierrot and Majid’s son meet, have a conversation we cannot hear, and then separate, has consumed much of the discussion about Caché—that is, when viewers notice the meeting at all. Many have failed to see Pierrot and Majid’s son in the frame, as the focal point of the shot is the brightest, largest figure in the image, a woman in the middle-ground with her back to the camera. For those who do notice, questions linger: What does this final moment mean? Were the two boys working together to create the tapes? Is someone else taping them? Did Majid’s son learn of the ways his father was wronged by Georges when they were children, and then elicit the help of Pierrot in a cruel campaign? Was Majid aware of the tapes, and did he take part in their creation? Of course, the implications of the scene extend beyond the moment itself. If Haneke has so cleverly hidden Pierrot and Majid’s son in this shot, and we happened to miss this on one or more viewings, what else did we miss throughout the film? What clues could help the viewer crack the mystery at the center of the film, whose name in English means “hidden.” Surely, in a film with that title, there must be something to find.

Our expectations, informed by our regular spectatorship of average thrillers, suggest Caché is a whodunit of sorts—a film with a mystery that is capable of being solved. But Haneke isn’t interested in unmasking the culprit of the eerie tapes; instead, he uses our expectations against us. Knowing that his audience, who have been conditioned by a lifetime of formulaic mysteries and thrillers, will expect closure at the end of his film, Haneke denies any such illumination, making that irresolution the film’s most persistent and itching quality. In doing so, Haneke weaves the unease of his film’s narrative into its multifaceted thematic concerns: He explores social apathy by portraying a complacent and decidedly European bourgeoisie within its First World perspective. He confronts political guilt and historical repression by addressing a buried page from France’s past, when, in October 1961, police beat and drowned hundreds of Algerian protesters, leaving their bodies in the Seine. He questions methods of surveillance and its uses of power, and through this, uses his formal technique to question the nature of an oblique reality. Through all of it, the director employs a masterful control over his formal presentation, leaving his audience to question how the film’s apparent clarity of purpose could result in more questions than answers.

Born in 1942 in Munich, Haneke maintains a private personal life. He grew up in Lower Austria, where his mother, actress Beatrix von Degenschild, and his father, theater director Fritz Haneke, left their child to be raised by his aunts in the middle-class suburb of Wiener Neustadt. Even in grammar school, Heneke became interested in drama and music, hoping to become a concert pianist or an actor. When he attended the University of Vienna, he studied Drama, Philosophy, and Psychology, and afterward became a literary critic. As Haneke scholar Catherine Wheatley noted, he was “a walking cliché of a young bourgeois intellectual of the 1960s,” given his affinity for philosophic discussion, modernist literature, and European art cinema. Haneke continues to admire Michelangelo Antonioni, Ingmar Bergman, Robert Bresson, Carl Th. Dreyer, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Andrei Tarkovsky—auteurs who unquestionably influence his films. His work as a director began, like his father, on the stage. In 1967, he transitioned to television, where he directed several made-for-TV films that show evidence of his later style: static time-images and protracted sequence shots; spare settings and emotionally remote, isolated characters; and a level of cinematic gamesmanship that brings into question the nature of reality, cinema, and perception.

The Seventh Continent (1989) was Haneke’s first feature released theatrically and, as is the case with most of his films, he wrote the script and directed from an original idea. Although screened at the Cannes Film Festival and submitted as Austria’s official entry to the Academy Awards, the response was not overwhelming. Benny’s Video (1992) and the multi-narrative 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance (1994) received similar attention, whereas his self-reflexive thriller Funny Games (1997) and social mosaic Code Unknown (2000) were each nominated for the Palme d’Or at Cannes. Still, the filmmaker did not receive vast international attention until his character study of control and sadomasochism, The Piano Teacher (2001), which earned the Grand Prix at Cannes. After his lesser-praised post-apocalyptic tale Time of the Wolf (2003), Caché was a resounding success both critically and commercially, earning him Cannes’ Best Director award. Haneke’s follow-up was his shot-for-shot remake, Funny Games, made for U.S. audiences in 2007. Though his only English-language feature was considered by many to be a failure, he returned to form with two back-to-back Palme d’Or winners, The White Ribbon (2009) and Amour (2012), the most highly awarded and commended films in his career. In 2017, Happy End proved that Haneke remains a premier and controversial figure in world cinema.

Thematically, Haneke’s films often involve social criticism, taking a cue from the “New Austrian Cinema” filmmakers before him who had assessed and critiqued their country’s fascist past with scathing representations of individuals who are socially repressed, resentful, and robbed of their values—bourgeois families that give into racism and aggression in order to preserve their identity. Haneke continues in that tradition, although he operates on a much wider, international scope. His themes of guilt, prejudice, and violence that pass through the generations speak to the Austrian past and culture in his earlier work, whereas, beginning with his French-language Code Unknown, he investigates societal issues that involve many European countries. But Haneke prefers to think of his films not as specifically tethered to a national identity, as the lessons in his work often prove universal and beyond nationalism. Formally, the influence of filmmakers such as Antonioni, Bresson, and Tarkovsky are evident in Haneke’s style. Consistent with each of these films is Haneke’s close observation of characters and spaces, and the discoveries of anachronistic details within the frame. All the while, he withholds narrative information to engage the viewer, claiming “the more radically answers are denied to him, the more likely he is to find his own.” This is true of Caché more than all other Michael Haneke films.

In a plot device that evokes David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997), Caché finds Georges and Anne Laurent in a similar predicament, having little information and searching for the reasons behind an anonymous, unnerving videotape of their home. Despite the stationary shot on the first tape, the image seems to say, We’re watching. We know. After arguing about its origin, Anne, disturbed from the tape, finds her husband frustrated by her lack of answers. She resolves to continue preparing their dinner and tries to talk about something else. Both of them are worried about their son, Pierrot, who has not yet arrived home from school. When Pierrot, late, finally joins them for dinner, they ask where he’s been. At Yves’ place, he explains; he always studies at Yves’ place on Tuesdays. Pierrot seems no more defensive about his whereabouts than any boy who wants to keep his life private from mom and dad. But watching closely, the preteen boy looks as though he’s harboring a secret from his parents. Not that they notice. Georges and Anne are apparently unsure of Pierrot’s routine, and what’s more, he’s a complete mystery to them. Haneke’s films often warn not to take for granted the potential disdain that children may feel towards adults, nor underestimate the horrible limitations of a child. Would The White Ribbon have contained the same unease if not for our suspicions of the children who inhabit the film’s pre-World War I village? Would either version of Haneke’s Funny Games have existed if the adults in the film had grasped the potential for psychopathy in their young guests? How would Happy End have worked without a morbid child at its center?

Pierrot was bound to be overlooked, given his cold family dynamics and the oppressive cleanness of his home’s interior design. The interior suggests their upper-class status without flashiness or pomp. Its lifeless walls of white, gray, and beige contain almost no artworks or evidence of their leanings, while the endless rows of shelving, populated with anonymous books, movies, and music, imply their cultured pretense. The Laurents maintain a comfortable bourgeoisie home in which its inhabitants move about in vacant halls like specters, once again channeling similar scenes in Lost Highway. They occupy what Haneke would describe as a “loveless” bourgeoisie world, largely understood through the uncommunicative Georges. To be sure, the home reflects Georges and his emotional distance more than anyone else in the family. Both Georges and his living space are alienating, completely devoid of warmth. He grows frustrated when the second tape arrives wrapped in the drawing of a face and bloody mouth—an image that channels a brief image from Georges’ memory. This interruption in their muted routine—the drawing’s stark red colors against the spareness of their home presents a contrast of color and emotion—feels jarringly out of place. But he refuses to discuss the real reasons for his anger with Anne. Georges has inherited his parents’ closed-off behaviors. When later he visits his mother (Annie Girardot), and the two engage in a seemingly straightforward conversation loaded with non-answers and dismissals, the viewer begins to see why Georges refuses to acknowledge that he knows more about the tapes than he’s letting on—he comes from a class of people determined to internalize emotion, avoid significant questions, and refuse to admit mistakes.

And so, Georges and Anne attempt to carry on with their lives by hosting a dinner party, which is interrupted when a phantom doorbell leads to another tape. This one is wrapped in a crayon drawing of a decapitated chicken head. The video features a trip to Georges’ childhood home. Now it seems apparent: the tapes are targeted at Georges. Regardless, Georges treats the reality of their situation as an inconvenience to the dinner party, while, with each new tape, Haneke tightens the screws with a growing sense of invasiveness. Using clues on yet another tape, the Laurents sleuth the location of a rent-controlled apartment building, and the building’s long hallway leading to a door. Georges confesses that he has “a hunch” about who might be sending the videotapes, but he refuses to elaborate because it “doesn’t concern” Anne—a position that causes Anne to break down and demand open communication. Regardless, Georges scouts the location on his own and at last knocks on the door in the video. A short man of Algerian decent opens up. It is Majid, Georges childhood friend whom his parents were once going to adopt, who recognizes Georges from his talk show and appears genuinely unaware of how Georges might have discovered where he’s living after so long. Georges confronts Majid about the tapes. He claims to know nothing about them. After the encounter, Georges tells Anne that no one answered the door.

Not long after, the Laurents receive another tape. This one shows Georges confronting Majid, but from an angle of a camera hidden in Majid’s apartment—meaning either Majid, or someone close to Majid, recorded it. The tape reveals that Majid was deeply disturbed and wounded by his encounter with Georges; he cried for an hour after Georges left. It also reveals that Georges lied to his wife. When Anne confronts him, he talks around his deceit, never admitting the full story. The same tape of Georges confronting Majid was sent to his superiors in public TV, and he promises to hire a lawyer to handle the matter. That evening, Pierrot does not come home. Has he been kidnapped by the same person sending the tapes? Georges and Anne search for him, calling his friends’ parents. Convinced that Pierrot has been kidnapped by Majid, Georges and Anne call the police. The authorities bang on Majid’s door, but his son, who remains unnamed, opens up. Majid and his son are both held overnight for questioning. On the ride to the police station, Majid looks inward, as though he’s worried about something, while his son looks at Georges with anger and contempt.

As it turns out, Pierrot was sleeping over at a friend’s house. But when he gets home, he’s curiously standoffish to his parents, if not downright angry at Anne. Pierrot suggests he’s jealous over his mother spending so much time with Pierre (Daniel Duval), a conversely warm and communicative family friend. But how would Pierrot know that Anne met with Pierre for coffee the previous day unless Pierrot was following them? The more likely explanation is that Pierrot knows what happened to Majid and his son the night before. With Pierrot home safe, all seems well until Majid calls Georges over and confesses, “I had no idea about the tapes.” In that same instant, Majid adds, “…and I wanted you to be present,” and then slices his own throat with a pocket knife. A sharp and sudden burst of blood sprays on the wall. Majid falls to the ground, dead. Only after witnessing this suicide does Georges tell Anne the truth, possibly even all of it: When Majid’s parents protested the Algerian War in Paris, they were among the hundreds massacred. Georges’ parents considered adopting the boy. But Georges, jealous and not wanting to share a room, told lies about Majid. First, he claimed to see Majid coughing up blood, hoping his parents would assume Majid had tuberculosis. When that didn’t work, Georges told Majid to kill the family’s troublesome rooster, claiming that Georges’ father wanted the rooster dead and its killing would put Majid in his favor. When Majid killed the bird, Georges told his parents that Majid did it as a threat. And with that, Majid was taken away to an orphanage.

In the aftermath, the tapes have stopped, but Majid’s son follows Georges into his office, demanding a confrontation. He unconvincingly claims he had nothing to do with the tapes, but then descends into a tirade: “You deprived my father of a good education!” With this, Georges seems certain of the culprit, although Haneke has not provided unshakable evidence. The famous last shot, which comes just after Georges’ memory of Majid being taken away to the orphanage, looks on Pierrot’s school. Inside the static frame, which remains onscreen for several minutes and through the end credits, shows after school commotion. Children run out and back into the school. Parents pick up their children in cars or wait for them on the sidewalk. Within the busy scene, as mentioned above, Pierrot and Majid’s son appear in the frame for a brief discussion, if the viewer is lucky enough to notice it. After Majid’s son looks around to ensure they’re hidden in plain sight, they have a brief, unheard discussion, and then separate. Questions remain for any viewer. Who is making these recordings, and why? What people or plot details have been hidden inside any given shot?

But such questions about the sender serve only the film’s MacGuffin—a mystery still debated among viewers and about which Haneke has kept silent. Caché remains inconclusive, intentionally so, as the director seeks more than the story-related outcomes of a typical thriller. As Catherine Wheatley observed, Alfred Hitchcock described drama as “life with the dull bits cut out,” whereas Haneke leaves many of the dull bits in, suggesting their importance. When Georges and a biker nearly collide in the street, their intense, angry reactions suggest something more beneath the encounter. Certainly Georges’ heightened state of defensiveness from the tapes is to blame, while his accusatory tone only makes matters worse. Still, for a moment, the viewer wonders the purpose of the scene. Is the biker the one leaving the tapes? Why is Haneke showing us this, except perhaps to employ a standard thriller device—the Red Herring—in order to enhance the MacGuffin? Later, we realize the scene further reveals Georges’ unwillingness to admit his guilt for something as simple as failing to look both ways before crossing the street. Even more frustrating for some viewers is the contrast between the apparent deliberateness in Haneke’s placement of characters, images, and formal technique to occupy the space of a thriller, while the story itself remains elusive. It’s a careful balance, requiring Haneke to give his audience just enough to feel some certainty in their interpretation without telling them what to think. He told an interviewer, “There’s always the fear of frustrating them. What do I have to indicate? What do I leave out? How much can I not spell out when constructing a film and still not frustrate the audience? ”

Haneke’s control over the cinematic apparatus is an astounding unification of form and content. Shots in Caché have been designed for the spectator to ask questions about what we see, both in terms of the images represented and the source of those images. Consider the opening shot of the film. A static image depicts the exterior of the Laurent home. Not until Georges and Anne begin to speak, and fast-forward the tape in their VCR, does it become apparent that what we’re seeing is a shot-within-a-shot—the VHS image on the Laurents’ television filling the frame. Several scenes in the film unfold in this way, where the diegetic film image is that of a source inside of the film: another camera, a news broadcast, or Georges’ television show. At other times, Haneke uses the same angle for Georges’ point-of-view as the videos sent to him. For instance, when Georges walks down the hallway to Majid’s apartment, the angle and height of the POV shot is almost identical to the same image on the tape. (At the very least, this should suggest to the viewer that videographer’s height is about the same as Georges—and therefore not shorter, like Pierrot or Majid.) In doing this, Haneke plays with the viewer’s expectations, forcing us to question the source and meaning of every shot through active participation. We become acutely aware of the formal techniques used from scene to scene, as they may provide some clue as to the central mystery. We begin to suspect every static shot, wondering, Could this be another tape? Early in the film, when the camera begins to move, we almost sigh in relief, if only for Georges and Anne’s sake, that the image is most likely not a tape. Of course, midway through the film, a tape arrives and the video captures the perspective of a passenger in an automobile. The frame turns to the left to reveal Georges’ childhood home. In a single scene, the tape has become frighteningly personal for Georges, but it also makes the mystery more complex for the viewer.

On a thematic-formal level, Caché requires the audience to examine the origins and uses of film imagery. What is Haneke showing us and why? Does the image originate from the filmmaker’s camera or a camera controlled by one of the characters? Is the viewer the only one watching the image, or are we watching a tape from someone’s perspective? Often we see images through Anne or Georges’ eyes, such as the latter’s dreams and memories: a sudden flash of Majid with a bloody mouth; the haunting memory, undoubtedly enhanced by Georges’ childhood lies, of Majid beheading the family rooster with a terrible, psychopathic expression on his blood-splattered face; and a final, disquieting memory from Georges in the end. In that final memory, the young Georges has hidden himself inside the family barn, as the shot from his perspective looks out into the courtyard. A car arrives from the orphanage to pick up Majid. Georges parents hide inside; meanwhile, two adults carry the achingly frightened Majid to their vehicle and drive away with the boy. Haneke cuts between reality and various perspectives with the same unannounced transitions as his cuts between a diegetic image and an image whose source is within the diegesis. As images change, the viewer must constantly question them. Are they the film’s diegetic presentation? Are they a source from within the film capable of being manipulated, paused, rewound, and forwarded? Has the image poured out of Georges memories or dreams, and if so, how has his mind shaped what we’re seeing? At any point in Caché, regardless of the image before us, the truth of the perspective is not only subjective but impossible to trust.

The intentionally conspicuous lack of objective truth in the film informs the film’s allegorical connection to France’s history, specifically as it relates to Georges. In the early part of the twentieth century, Algeria had begun a political movement to acquire independence from France, which had ruled as a colonial power since 1827. Prior to World War II, France had promised Algeria sovereignty, but when they maintained their imperialist hold after the war, the Algerians organized and rebelled. While seeking political recognition with the United Nations, Algerian fighters in their Front de Libération Nationale led a series of violent attacks, culminating with the bloody Battle of Algiers (1956–57). On October 17, 1961, thousands of Algerians gathered in Paris to protest a new curfew for Muslims living in the city, enacted by Maurice Papon, the head of Parisian police. (It should be noted, Papon was convicted of crimes against humanity in 1999; as a Vichy official, he helped organize Jews for deportation and extermination by the Nazis.) Papon responded to the protest of his curfew with a police action that led to hundreds of Algerians dead, their bodies tossed indiscriminately into the Seine, while thousands more were rounded up into “detention centers”. The massacre had been covered up and quieted for decades, even denied by the state, until Papon’s trial, after which the French government was finally forced to acknowledge the massacre.

Caché, then, engages in a stark critique of the violent colonial past and the denial of the postcolonial present, using Georges as an analogy for France’s unwillingness to openly acknowledge its role in the 1961 massacre. Georges’ lies and the disturbing memory of Majid being carted away have been suppressed. Along this line of metaphoric thinking, Anne might represent the integrity of historical accuracy and its often wounded, twisted, and manipulated state, or the people who continue to suffer because they remain uninformed. But such readable interpretations are less important to the film’s meaning than Georges’ symbolic guilt. Georges represents how the state buried the atrocity in their distant memory, and moreover, Haneke has acknowledged that Georges could represent any country that has conveniently denied its history: Americans ignoring their genocidal treatment of Native tribes, African slaves, or Japanese Americans during World War II; the British Empire’s colonial rule across the globe; Australia’s treatment of aboriginals; and the potential metaphors go on. The mystery, meanwhile, provides a cinematic context, through tapes that prod the suppressed guilt and make the truth impossible to deny, while also holding the viewer’s interest.

Caché would not exist without Georges’ guilt and his unwillingness to face the lies he told as a child. Had he calmly talked with Majid during their first encounter in the film, Georges could have made a long-overdue apology; though, Majid hardly seemed expectant of one. Instead, Georges’ guilt perpetuates the story. He refuses to tell Anne what he suspects is going on. He refuses to speak openly to his mother about the tapes, about his mother’s feelings concerning the child they did not adopt, or about his role in Majid’s fate. To others, Georges describes Majid as a crazy person terrorizing the Laurent family, and perhaps this is how he must see Majid: as an enemy that represents a shameful memory. If Georges is France as the above analogy suggests, then perhaps the film’s message is that the French are too quick to blame others, such as the Algerians, and not quick enough to look inward, as represented with the broken Laurent family. Then again, all of these themes are concealed beneath the surface of the film. The audience writhes, unable to bring the mystery to any conventional, satisfying, or absolute resolution. Film scholar Paul Arthur wrote that Haneke’s films possess “a creative sensibility befitting our contemporary hash of dread, disgust, and rage,” offering something that speaks to our powerless species. Ever-paranoid about the impending apocalypse and various social crises, we remain unable to accurately diagnose or prevent our cultural disorders in the moment. Caché reflects this in our experience.

Haneke has compared Caché to a Russian nesting doll, describing it as intentionally layered, with an obvious surface that contains several concealed layers: “The same story can be seen on different levels, can represent different levels: the personal level, the family level, the social level, the political level.” The film is emblematic of Haneke’s rallying against the “American cinema of distraction” that “deprives the spectator of the possibility of participation.” Disengaged viewers watch mindless entertainment without being instructed on an intellectual level, or feeling delighted on artistic and emotional levels. At the same time, Haneke avoids discussing what his films mean and refuses to explain his authorial intent. The viewer, therefore, becomes an author in their spectatorship of a Haneke film, in essence writing the meaning of his films for themselves. We become responsible for assigning meaning to films that are a challenge to assess and define given their uncomfortable narratives, difficult formal treatment, and resistance to formative scholarly insight. Even cinéastes cannot delve into Haneke’s interviews or remarks about his films and hope for him to pinpoint his artistic goals. As a result, Haneke’s audience may simply remain confused as to what lessons they should have learned or how they should react.

Caché portrays the tragedy when an individual or country cannot remember their uncomfortable national or personal history, or more accurately, do not want to—as Haneke told an interviewer, by denying history a person “pulls the blanket over our heads and hopes that the nightmares won’t be too bad.” Though its story mechanics may be deceptive and challenging, what persists is the discussion around the film, how it has confounded, foiled, and intrigued viewers of European cinema since 2005. The experience of watching Caché, and what the viewer derives from the experience, comes from within the spectator, not the narrative. The sender of the tapes is less important than the guilt they evoke, just as the truth of Yvon’s joke is less important than the laughter it produced. Each individual assigns a unique, projected meaning informed by their personal desires, interests, and preoccupations. In a sense, though, this is true of all art and cinema. What makes Caché different is how brilliantly Haneke transforms the viewer into the author and participant, but then also weaves those intentions into the thematic consequence of the picture. Through his uses of form, Haneke shows us that there are endless possibilities in how we might view the world; he suggests that such a multitude of perceptions should be examined, considered, and never taken for granted.

Bibliography:

Arthur, Paul. “Endgame.” Film Comment, Vol. 41, No. 6, November/December 2005, pp. 24-28.

Badt, Karin Luisa. “Family is Hell and So is the World: Talking to Michael Haneke.” Bright Lights Film Journal. 1 November 2015. http://brightlightsfilm.com/family-hell-world-talking-michael-haneke-cannes-2005/#.WkwheCOZOu4. Accessed 2 January 2018.

Horwath, Alexander. “Michael Haneke Interview: Uncut.” Film Comment, Vol. 45, No. 6, November/December 2009, pp. 26-31.

Wheatley, Catherine. Michael Haneke’s Cinema: The Ethic of the Image. New York: Berghahn Books, 2009.

Amour

Amour  Shutter Island

Shutter Island  Knives Out

Knives Out