Mercy

By Brian Eggert |

Mercy is a movie the world doesn’t need right now. A whodunit set in a dystopian Los Angeles, this tone-deaf Amazon MGM Studios production feels woefully mistimed. It achieves the unthinkable by adopting three contentious issues—our culture’s embrace of AI, authoritarian policing, and capital punishment—yet it says nothing of consequence about any of them. Never mind that, as Mercy opens in theaters, AI is scrambling the nature of truth. And ignore that American cities are teeming with aggressive, prejudiced ICE agents, who seemingly have no limits to the terror they can inflict in the name of this administration’s campaign of fear. In this climate, a movie about a dispassionate AI judge dispensing fatal justice while relying on evidence collected by an invasive surveillance state feels eerily germane. However relevant this scenario may be, it’s less a reflection of the Zeitgeist than a superficial attempt at topicality. Worse, although some elements of the premise have potential, Timur Bekmambetov’s chaotic direction and star Chris Pratt’s flat performance neutralize any hope of provoking thought or entertainment value.

Last year, a disastrous new take on War of the Worlds premiered on Amazon Prime and became a widespread joke. Ice Cube starred in this so-called screenlife version of H.G. Wells’ classic, with the action unfolding on various desktops, smartphones, and security cameras. It was a laughable affair compared to Steven Spielberg’s exceptional 2005 version. Similarly, Mercy is a (mostly) screenlife movie that resembles a different Spielberg film, Minority Report (2002). Both explore a futuristic form of justice, and its most zealous proponent experiences firsthand how the system he helped establish is deeply flawed. In Spielberg’s film, a “Precrime” police division relies on three clairvoyant mutants to predict murders, and the cop assigned to arrest people before they commit their crime is himself accused of a future murder. In Mercy, a detective who advocates for an AI judge, which gives defendants 90 minutes to prove their innocence before executing them, finds himself on trial for the murder of his wife. Guilty until proven innocent, he must rifle through floating panels from virtual databases and security footage to clear his name—again, like Minority Report. The accused cop calls the setup a “kill box,” and sure enough, the new AI program has overseen 18 cases and executed as many people.

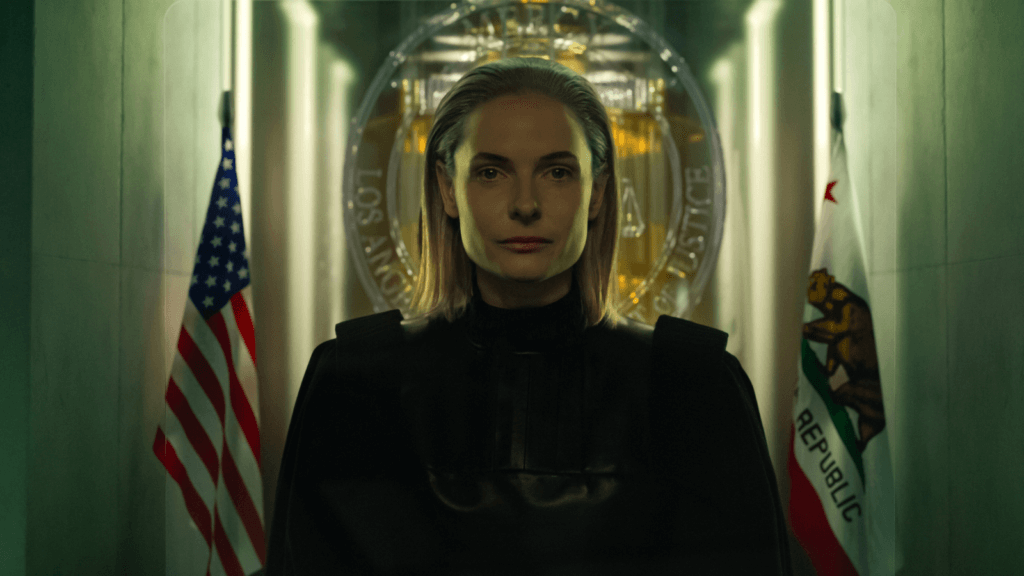

The concept sounds like a good elevator pitch. But the more you think about the logistics, the less sense it makes. Why, for instance, do defendants only get 90 minutes to prove their innocence? This is an arbitrary timeframe. Pratt’s character, Detective Chris Raven—a name that sounds like the hero of a 1990s cop show canceled after one season—wakes up strapped to a chair, facing an AI judge named Maddox (Rebecca Ferguson). An artificial image speaking from a screen, Maddox tells Raven he’s on trial for murdering his wife, and in 90 minutes, he will receive a lethal “sonic pulse” unless he can absolve himself. Some defense attorneys receive weeks or even months to put together a defense strategy. But here, the defendant must work against the clock to raise a reasonable doubt in the “Mercy” program. Maddox claims to rely on facts, which feed an algorithm that calculates the probability of guilt. Raven’s score begins at 97.5%, and he must reduce that to below 92% to save himself. However, this device ignores how juries use facts to determine whether there is reasonable doubt, which is based on a feeling. AI does not have feelings. Or does it?

That’s the “lesson” Mercy, written by Marco van Belle, hopes to impart: humans and AI can both make mistakes, despite their claims otherwise, so let’s cut AI and the justice system some slack and try to make them better, shall we? But that lesson ignores the damage done in the process—how human beings, even cops, can be duplicitous and deceptive, and AI models can make outright incorrect assumptions based on misinterpretations of available information. Mercy takes an apologist’s stance about AI that still requires some debugging, while also making excuses for Raven, an abusive alcoholic and a lousy cop who, we eventually learn, helped convict at least one person wrongfully executed by the ironically named “Mercy” program. In video evidence taken from doorbell cameras, police body cams, security networks, and drone footage, the movie shows us Raven’s toxic behavior with his family. He rationalizes his angry, drunken outbursts as “fiery,” but his teenage daughter, Brit (Kylie Rogers), describes him as “dangerous.” It’s a role that’s supposed to be a flawed hero, I suppose. But it reminded me of another of Pratt’s sci-fi roles in Passengers (2016), where he plays a creep and stalker whom the movie presents as a hero.

Mercy also implies that Maddox is more than emotionless programming and, after implanting serious doubt about its intentions, attempts to vindicate the AI judge. While building a case against Raven for an alleged crime of passion against his estranged wife, Nicole (Annabelle Wallis), Maddox looks at him with disapproving eyes. Ferguson’s performance suggests the AI derives pleasure from his failure to mount a convincing defense, as though it looks forward to killing him. The judge program also insists on being addressed as “your honor,” apparently taking pride in its position. But isn’t pride an emotion? Maddox’s behavior is inconsistent; it does whatever the filmmakers need in a given moment, such as reminding Raven to stop delivering unnecessary backstory during an exposition dump. At one point, the AI seems to have a crisis of conscience, and when Raven identifies the real killer, it defies its programming to do the right thing. Shouldn’t everyone be terrified that the AI went against its coding to make a conscious decision? I was also confused about why Maddox, late in the movie, cannot stop the execution countdown despite acknowledging Raven’s innocence—other than being a cheap device to build tension.

If the convoluted storytelling weren’t maddening enough, Bekmambetov directs a frenzied array of screens, edited by Austin Keeling and Lam T. Nguyen, into a visual hodgepodge. Mercy follows the streamer storytelling model by restating the conflict every few minutes, complete with an onscreen countdown and Maddox periodically reminding Raven of the stakes. It’s well-suited for those with short attention spans, and viewers distracted by their phones should have no trouble following the plot. To be sure, nothing feels more anti-cinematic than watching a character who’s bound to a chair, scrolling through digital files and databases, looking for evidence. This poor use of the large-screen format begs the question: Why, of all movies, has the studio distributed this on IMAX screens and in 3D? Fortunately, my press screening spared me the 3D version of Mercy, but one can imagine the experience: almost touchable digital screens floating before the moviegoer, as though a computer desktop had a depth of field. Along with a distracting amount of ADR and an overblown finale with one too many twists, Mercy is a frustrating watch that tests the viewer’s patience.

Mercy remains uncritical of the surveillance state it depicts, never concerned about its government’s unrestricted access to private devices, dependence on unreliable AI, or chilling support of an instant death penalty. By contrast, Minority Report presented the ever-watching security infrastructure as an obstacle to overcome, thereby underscoring its problematic role in society. Bekmambetov’s movie doesn’t have this, or much of anything else, on its mind. It’s set on delivering a real-time murder mystery in less than 100 minutes, with only a fleeting curiosity about the moral and societal implications of the world it depicts. It’s a tedious watch for those tired of reading headlines about how AI is going to change the world (despite it spreading little more than slop and intellectual laziness on a mass scale) and about government forces spreading fear through over-policing. Indeed, a movie that redeems AI and unreliable police officers after messing up an investigation feels like the antithesis of escapist entertainment at this moment.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review