Master Gardener

By Brian Eggert |

“To plant a garden is to believe in tomorrow.” — Audrey Hepburn

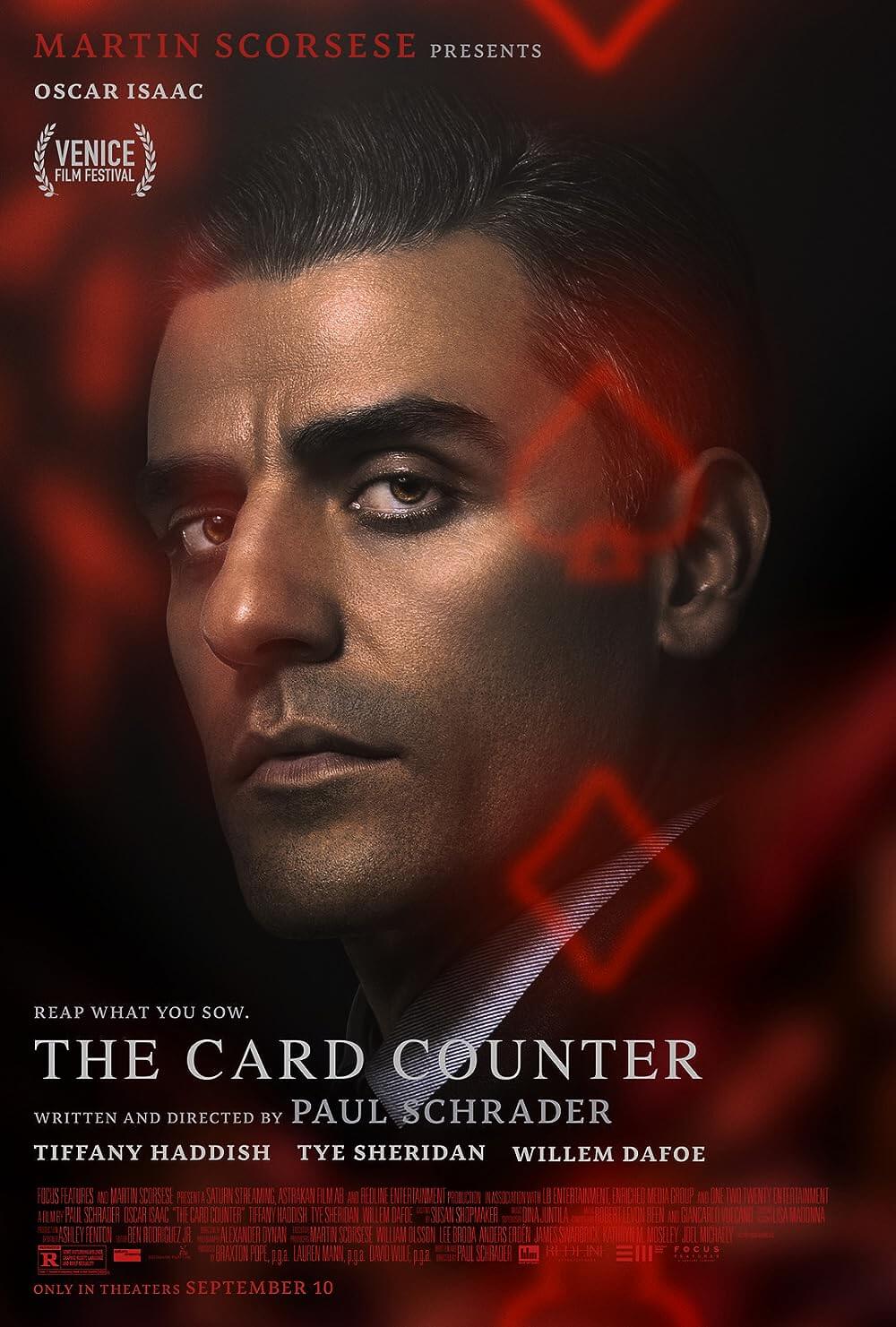

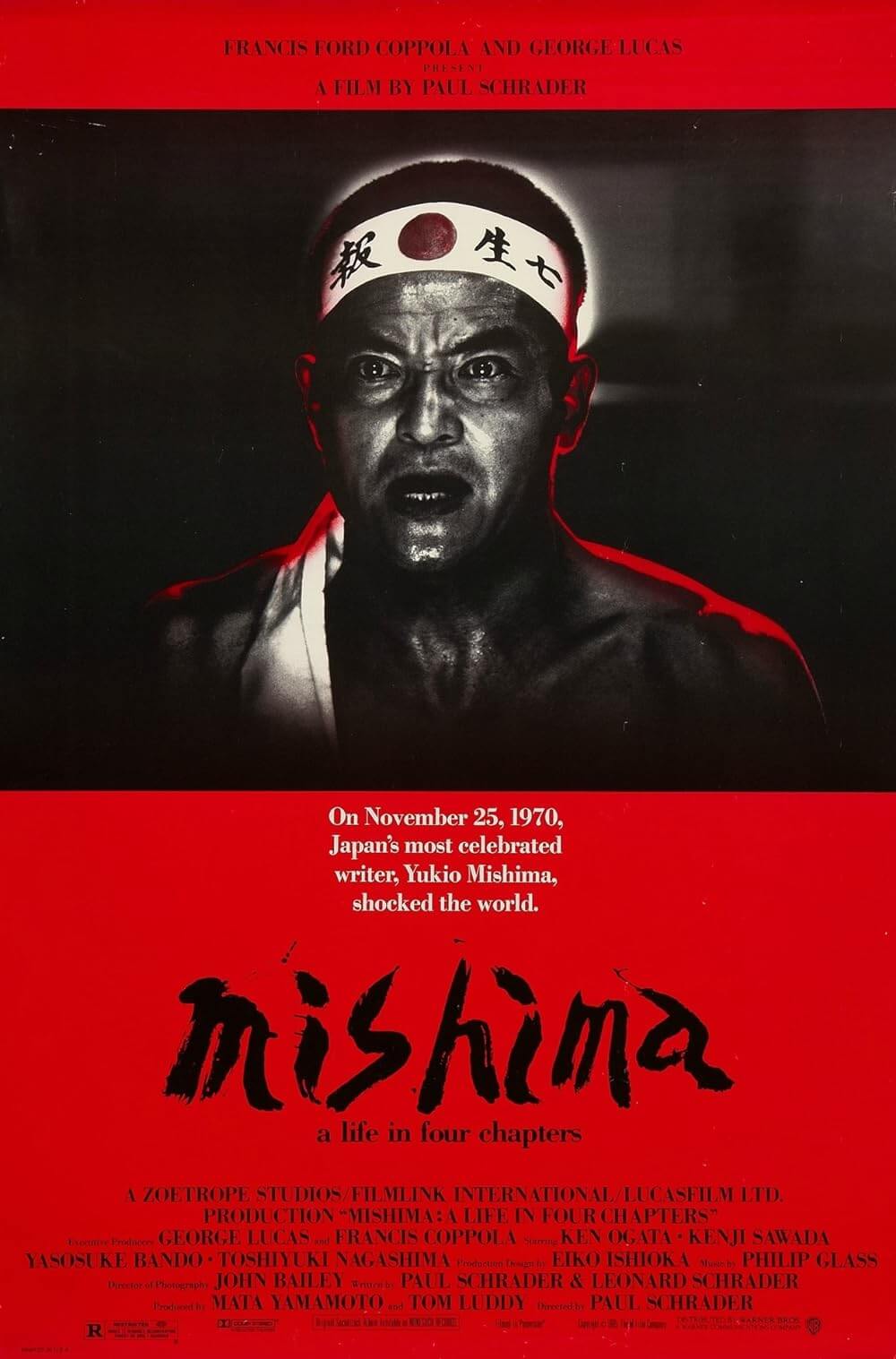

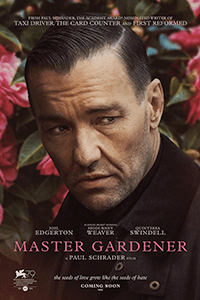

Master Gardener concludes writer-director Paul Schrader’s loose trilogy that began with his brilliant First Reformed (2018) and continued in 2021 with The Card Counter. Some have called the three films Schrader’s “Tortured Men” trilogy or his “Man in a Room” trilogy. However they’re lumped together, all three focus on fixated men who cannot forgive themselves for their troubled pasts, devote themselves to singular tasks to occupy their minds, and spend their downtime in austere rooms committing their inner thoughts to a journal. But it’s more than a trilogy. Schrader has revisited this theme repeatedly since penning Taxi Driver (1976), evidenced in Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985) and Light Sleeper (1992). It’s a setup he borrows from one of his favorite films by French director Robert Bresson, Diary of a Country Priest (1951), about a disenchanted priest whose body and faith rot from the inside. The films serve Schrader as a therapeutic method of working through his lifelong struggles (with substance abuse, depression, sex addiction, religion, and so on). If Master Gardener feels like little more than a variation on a theme, its performances and specific interest in horticulture result in appreciation for an otherwise minor effort for a major filmmaker.

Joel Edgerton plays Narvel Roth, the solitary caretaker of Gracewood Gardens, owned by the wealthy and prickly Norma Haverhill (Sigourney Weaver). Narvel is another of Schrader’s severe protagonists and embodies the minimalist style of Oscar Isaac’s poker player in The Card Counter. He considers every feature, not unlike the “conspicuous display” of the garden: his hair is buzzed short on the sides and slicked down on the top; he wears the same solid black tops and gray overalls; and he maintains an unemotional, controlled exterior. He takes his job just as seriously. “Gardening is a belief in the future,” he narrates from his journal early in the film. “A belief that things will happen. A belief that change will come in due time.” Though he owns a laptop, Narvel writes longhand like all of Schader’s tortured souls, rhapsodizing about the history of gardens and the enchanting growth patterns of certain flowers. He also has romantic ideas about the “exchange” between human beings and the soil, and despite his cleanliness, he’s not opposed to stuffing his face in the dirt to appreciate its scent or walking barefoot in the garden to connect with the earth.

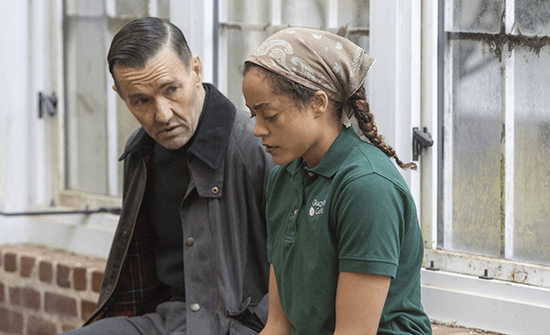

But a wrinkle forms on Narvel’s freshly ironed life when Norma asks him to take on her twentysomething grand-niece, Maya (Quintessa Swindell), as an apprentice. Norma won’t speak to Maya at first, leaving her for Narvel to welcome. She resents her late niece’s wild ways, which, according to Norma, led to Maya’s mixed-race parentage. Given that Gracewood Gardens resides on the site of a former plantation, there’s an implication of Norma’s racism that becomes ever more apparent as the story unfolds. And then there’s Narvel, whose control masks his past and its many secrets. In a quiet but shocking moment, Narvel undresses in his small home on the grounds, revealing that his body is covered in Nazi symbols and white supremacist slogans. Every moment after we learn about Narvel’s past is filled with tension and questions about his identity. Later, in a series of randomly inserted flashbacks, Schrader reveals that Narvel was a killer for an underground crypto-fascist group, but he flipped to avoid a prison sentence. Leaving behind a family, he has spent the last decade in witness protection.

This doesn’t bother Norma, who occasionally beds her gardener, but not before admiring his ink with eerie fascination. So when she finally talks to Maya and calls her “impertinent,” she says the word with a sense of her own racial superiority that proves sickening. Unfortunately, Norma is unconvincing as written, often feeling awkwardly over-the-top in an otherwise restrained film. Narvel fares better. He has not only hidden his past but changed as a result of gardening, and his personal reinvention is believable thanks to Edgerton’s intense presence. Narvel works alongside several people of color and welcomes Maya as well; the two even tiptoe around a romance. He teaches her how to garden and gives lessons about horticulture and botany; she lets her attraction be known. When she shows up to work with bruises, having been battered by a possessive drug dealer, Narvel vows to help. Fortunately, Master Gardener avoids an actionized scenario where the ex-killer comes out of retirement to defend his new lover. A lesser film would have gone there. But Schrader has more on his mind concerning race and reconciliation, so much so that when his character inevitably becomes violent near the climax, the director rushes through the moment, rendering it anticlimactic (a similar situation occurs in The Card Counter).

This doesn’t bother Norma, who occasionally beds her gardener, but not before admiring his ink with eerie fascination. So when she finally talks to Maya and calls her “impertinent,” she says the word with a sense of her own racial superiority that proves sickening. Unfortunately, Norma is unconvincing as written, often feeling awkwardly over-the-top in an otherwise restrained film. Narvel fares better. He has not only hidden his past but changed as a result of gardening, and his personal reinvention is believable thanks to Edgerton’s intense presence. Narvel works alongside several people of color and welcomes Maya as well; the two even tiptoe around a romance. He teaches her how to garden and gives lessons about horticulture and botany; she lets her attraction be known. When she shows up to work with bruises, having been battered by a possessive drug dealer, Narvel vows to help. Fortunately, Master Gardener avoids an actionized scenario where the ex-killer comes out of retirement to defend his new lover. A lesser film would have gone there. But Schrader has more on his mind concerning race and reconciliation, so much so that when his character inevitably becomes violent near the climax, the director rushes through the moment, rendering it anticlimactic (a similar situation occurs in The Card Counter).

Still, tattoos aside, Schrader avoids challenging the audience with Narvel. For instance, the director shows dreams and memories from Narvel’s head, featuring his falling out with his former racist pals. But the film alludes to but avoids showing Narvel, say, burning a cross on someone’s lawn or worse, even though the character alludes to such behavior. It might have been impossible for the viewer to forgive Narvel had Schrader shown him performing hate crimes, and as a result, the decision feels like a cop-out next to the extremes and redemption seen in a comparable film, American History X (1998). Moreover, when Maya learns of Narvel’s past, she overcomes her reservations rather quickly, leading to a richly symbolic but emotionally flat sex scene—covered in his fascist tattoos, a nude Narvel drops to his needs to perform cunnilingus on a Black woman and his future wife—which Schrader and cinematographer Alexander Dynan stage in beautiful shadows. It’s provocative imagery that Schrader hasn’t backed up with an understanding of Maya; the filmmaker is more interested in Narvel’s redemption, leaving Maya’s forgiveness underdeveloped.

On the festival circuit, Schrader has told the press that his trilogy is about broken men who find redemption. However, Schrader’s view of redemption remains unconventional at best, and brutally self-destructive at worst. In First Reformed, Ethan Hawke’s priest likely died before he could achieve a final redemptive act; and if he had lived, the act would have been described by some as terrorism. Isaac’s character in The Card Counter finds redemption through self-punishment, atoning through self-imposed institutionalization. By comparison, Narvel’s redemption adheres to a more classical and even optimistic model, which, given the other entries in this trilogy and the director’s body of work, feels almost uncharacteristic for Schrader. Still, the finale might be the only true redemption in the trilogy. It’s ushered by flowery imagery throughout the film, including a gorgeous dream sequence of Narvel and Maya driving at night through a blooming landscape that looks like something out of Annihilation (2018)—even the score by Devonté Hynes sounds like an electronic hum under an Alex Garland film. Such visuals and winding music suggest a cycle of self-repair and rebirth for both flora and Narvel.

Whereas First Reformed felt like an open wound and The Card Counter seemed like fresh stitches, Master Gardener is less immediate and painful. The tone puts the characters at a remove, in part because some of them feel underwritten, in part because the filmmaking feels less urgent than its two predecessors. The 76-year-old filmmaker, who has endured some ill health and hospitalization in recent years, is convinced he only has maybe one film left in him. Master Gardener feels like he’s waning a bit, at least in comparison to the first two films in his trilogy. Even so, there’s an affecting sense of the Kantian sublime in the film, which equates the primal quality of Nature with the extreme emotions burning under Narvel’s chilly exterior. “The seeds of love grow like the seeds of hate,” Narvel says. Although one might wish the narrative were as passionate, it’s easy to admire Schrader’s thematic concerns and see him working through his own obsessions to a rare, hopeful conclusion. Narvel calls gardening the “creation of order, where order is appropriate.” In the same way, Schrader’s trilogy makes order out of cinema, and we can sense that he needs that order as vitally as Narvel needs gardening.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review