Luce

By Brian Eggert |

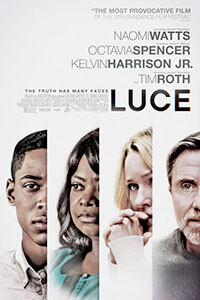

A screen adaptation of JC Lee’s off-Broadway play, Luce is a provocation aimed at the sociopolitical zeitgeist, asking its audience to quarrel over the complexity of the moral questions it raises. If you hold true to any ideals concerning racism, the privilege and expectation of class, accusations of sexual assault, identity in America, violence in schools, or the lasting effects of slavery, chances are you will walk away from the film with some strong feelings. Contributing to the screen story along with Lee, Nigerian-American director Julius Onah, whose forgettable The Cloverfield Paradox from last year seems like the work of another filmmaker, assembles a brilliant cast that gives impassioned performances. Onah navigates a situation that recalls the form and content of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989), in that he employs a stagelike drama to ask questions about America for which there are no right answers, just an ongoing dialogue, which the material hopes the audience will investigate for themselves.

Luce is a debate prompt. It even invokes the setting of a high school debate, a stage-within-a-stage to talk about its issues. In that sense, the playwright’s material openly acknowledges its relationship with the audience, hoping the drive home afterward will be a loaded conversation about serious issues affecting America today. It centers on African American teenager Luce Edgar, who served as a child soldier in an Eritrea “war zone” until a decade ago when he was adopted by Amy and Peter Edgar (Naomi Watts and Tim Roth, reteaming in husband and wife roles after the remake of Funny Games). Kelvin J. Harrison stars as Luce, having already impressed with his breakout role in It Comes at Night (2018). After years of processing the experiences of his early life, Luce is now poised and thriving under a veil of white privilege, impressing everyone with his personal, academic, and extracurricular achievements, not to mention the promise of his future.

The son of proud parents and a particular favorite of the school principal, Luce’s life seems to be picture-perfect until his history teacher, Harriet Wilson (Octavia Spencer), reads a paper he wrote from the perspective of Frantz Fanon, the post-colonial philosopher who wrote, “Violence is man re-creating himself.” Ms. Wilson, disturbed by the content of the paper, which nonetheless fulfilled the requirements of the assignment, goes into Luce’s locker and finds a bag of illegal fireworks. She assumes the worst and raises the issue with Amy in a parent-teacher conference. Despite them both dismissing Fanon as obscure—the two adults apparently hold no interest in postcolonial studies, resolving that Luce “probably stumbled onto Frantz Fanon on the internet”—the matter becomes a concern for Amy and Peter. They begin to question Luce’s intentions, doubting whether the years of deprogramming failed. Is Luce secretly a radical? Or does Ms. Wilson harbor a secret grudge against the star student, as Luce claims?

Looking closer at their adopted son, the parents reveal themselves, from Amy’s jealous support to Peter’s willingness to acknowledge that Luce might be trying to antagonize his teacher. At the same time, Luce hints that Ms. Wilson may have an agenda that holds him and other students up to an unreasonable standard. His friend DeShaun (Astro) and ex-girlfriend Stephanie Kim (Andrea Bang) have been the target of Ms. Wilson’s attention, as she outed the former for marijuana use and hinted that the latter should be an example to others after some rumors of sexual impropriety. Ms. Wilson says that “context matters,” and she wants her Black students to avoid becoming victims of stereotyping, but she seems to ignore that there’s a problem with asking a Black kid with a troubled past to constantly live up to the expectations that would be placed on a white student. It’s another form of tokenism, and she cannot see that. Meanwhile, whenever his parents try to get at the truth, Luce looks suspiciously innocent, while the facts of the situation don’t always align.

Without giving too much away about a film that serves as a social thriller as much as a polemic, Luce seems to confirm the audience’s worst fears about its characters to make a point. The material confronts wokeness with a student that orchestrates acts of elaborate revenge, another student that fabricates her victimhood and uses it as a weapon, and parents complicit in the worst way. It calls out the trouble with confirmation biases, and then it proves those biases to be true among its characters. The screenplay tends to feel on-the-nose, except it’s not exactly clear what it’s trying to expose, aside from everything. The implications leave the film open to misinterpretation. With that, it’s important to avoid the temptation to view everything that happens in the film as making a grand statement about these issues as wide-ranging truisms, even though the screenplay waves its “this is about America” flag more than once. Instead, the film operates better under the adage: “You never really know what’s going on with people.”

What works best about Luce is not the post-film conversation. Admittedly, the film is too obviously an attempt to motivate a dialogue; you can see Lee and Onah hoping to arouse the viewer into a debate, maneuvering to implant suspicion, ambiguity, and doubt at every turn. It’s difficult for a film like this to take us by surprise after a while because it has been so elaborately engineered to instigate. But it does garner our appreciation for its craft. The incredibly acted scenes are immersive, with Harrison Jr. delivering a cagey performance, where it’s apparent that Luce’s real self is always a layer or two removed from what we’re seeing. The scenes between Watts and Roth are loaded as well, while Spencer has rarely been better. Luce is at its best when the plotting functions as a puzzle and the actors keep us guessing about their characters’ motivations. There’s no sense of truth to derive from the deeply theatrical experience, but the experience itself engages.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review