It Was Just an Accident

By Brian Eggert |

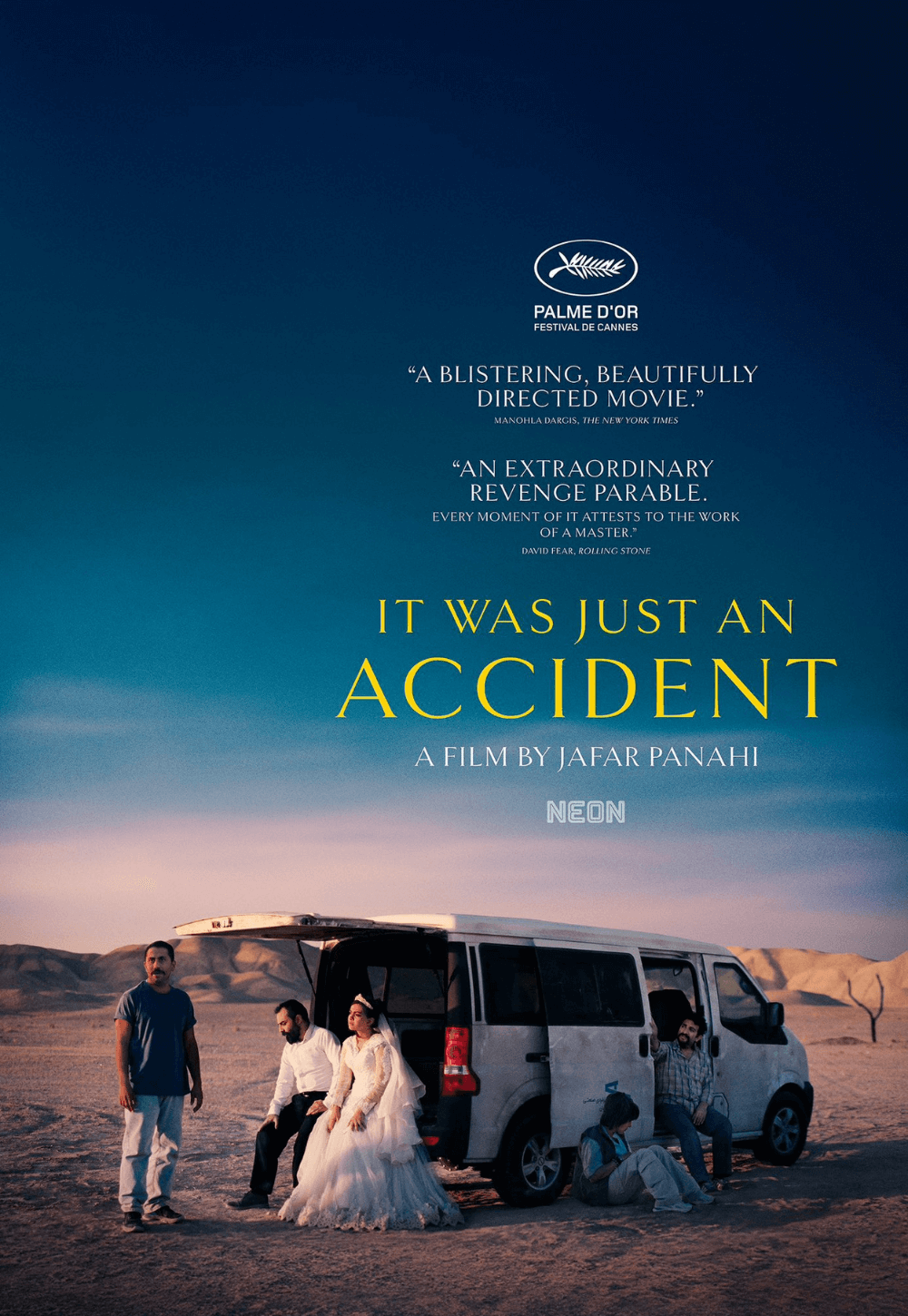

With It Was Just an Accident, Iranian director Jafar Panahi presents one of the year’s most vital films: a searing story that’s both specific and allegorical, a drama about political vengeance, a slow-burning morality play, and an unlikely satire of a broken system. Once the central dilemma sets things into motion, the characters spend much of the film driving around, trying to figure out what they should do—recalling the work of another Iranian director, Abbas Kiarostami, whose Taste of Cherry (1998) is similarly mobile. For Panahi, the driving is contemplative. One character even references Waiting for Godot, and sure enough, Panahi’s script feels influenced by Samuel Beckett’s play about two men who stand by a leafless tree, waiting for their salvation to arrive (spoiler: it never does). In Panahi’s film, the question is whether or not to bury someone alive next to a similarly bare tree. It’s a prompt that reverberates beyond the screen, interrogating modern-day Iran, or any country with an oppressive government, as though reminding them that they’re not immune or impervious to retribution. An essential film for today, it’s also thoughtfully crafted and engrossing in its immediacy.

Panahi’s film won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival this year. The victory went to It Was Just an Accident, of course, but also to the helmer whose last fifteen years have been shaped by discord with the Iranian government. In 2010, officials charged Panahi with producing anti-government propaganda and, after his conviction, sentenced him to six years in prison and a twenty-year ban from filmmaking. The imprisonment, which subjected Panahi to harsh interrogations and solitary confinement, didn’t last; the government allowed him conditional bail and moved him to house arrest after three months. Though authorities still forbade him from making films, Panahi found ways to shoot secretly, capturing This Is Not a Film (2011) entirely from within his house on an iPhone, before a colleague smuggled it out of the country. He followed that with Closed Curtain (2014), Taxi (2015), 3 Faces (2019), and No Bears (2022), each of which stars Panahi as a fictionalized version of himself, allowing him to remark on his captivity and his government through his art.

In July of 2022, when Panahi visited Tehran’s infamous Evin Prison to inquire about fellow directors arrested for supporting mass anti-government protests, Iranian authorities detained him on the spot and resolved to enforce his original six-year sentence after all. Many critics of the regime censured this action for its lack of due process, calling it a kidnapping. After six months inside, Panahi began a hunger strike in early 2023 that earned headlines, reigniting widespread condemnation of this and similar abuses of authority. Many believed Panahi, then in his early sixties, wouldn’t survive the strike or imprisonment. However, just two days after Panahi’s strike began, Iranian authorities unexpectedly released him. He was not only freed but allowed to make films again. It Was Just an Accident marks Panahi’s first film since his release, and it feels charged with the outrage and injustice of his imprisonment and brutal interrogations, as well as stories he heard from those who endured much worse.

The film opens with an accident. Late at night, Rashid (Ebrahim Azizi) is driving home with his pregnant wife and young daughter when, distracted, he hits a dog with his car. Afterward, the car breaks down. Rashid’s wife calls it a “sign.” Of what? That won’t become clear until the climactic scene. In the meantime, Panahi switches the perspective to Vahid (Vahid Mobasseri), who works at the garage where Rashid asks for help. Vahid hears him first and recognizes the distinct clack-squeak sound of the prosthetic leg belonging to Eghbal, a cruel guard from his time in prison. Vahid and several others were detained and tortured for protests concerning workers’ rights and the resultant hunger from unpaid wages. Eghbal, the worst among his tormentors, was known among prisoners as Peg Leg, and Vahid suspects Rashid is Eghbal. So, he follows the family home and waits for Eghbal to be alone.

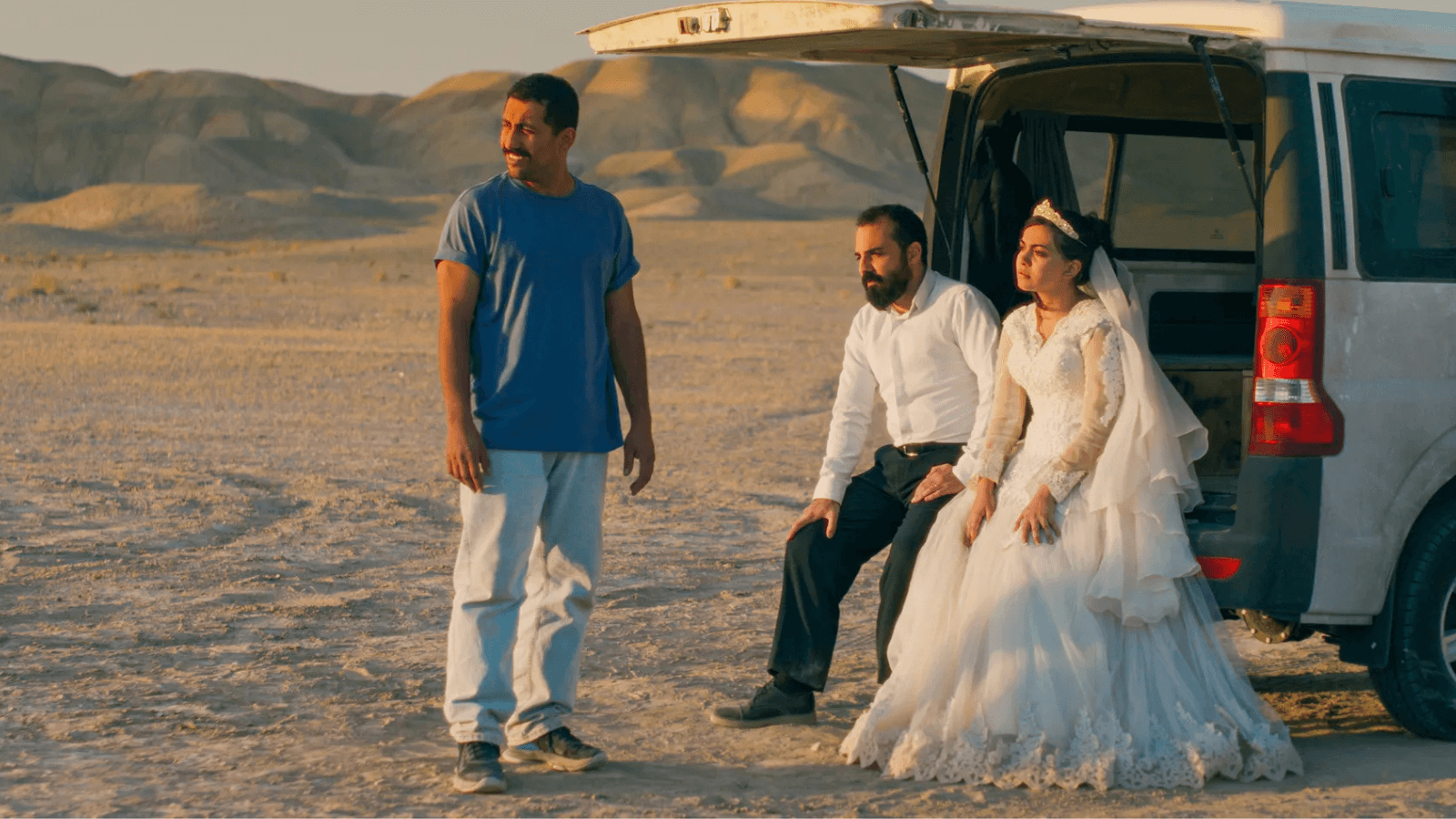

Shot with urgent, handheld camerawork by cinematographer Amin Jafari, the kidnapping that ensues follows Vahid in a van, trailing the suspected Eghbal on a city street. Vahid’s plan isn’t slick or well thought out; it’s the impulsive action of a desperate and angry man. He pulls alongside Eghbal in his white panel van, opens the door to knock him down, and then knocks him out with a shovel. The next shot finds Vahid in the desert, digging a hole and shouting at the suspected guard. However, the man Vahid drags into the shallow grave, surrounded by a sprawling desert and mountains in the distance, sows doubt as to his identity—enough so that Vahid feels he must be sure. He ends up meeting with Shiva (Mariam Afshari), a wedding photographer who, in a detail that tells us who she is, casually appears without a hijab. She’s in the middle of a gig for a soon-to-be-married couple in their tux and gown. The groom (Majid Panahi) objects to the interruption, but the bride, Goli (Hadis Pakbaten), and Shiva suffered under Eghbal. They want vengeance; everything else can wait.

Much of the film involves Vahid driving this group around in the van, inside of which the suspected Eghbal has been blindfolded, drugged, and restrained in a wooden trunk. Neither Shiva nor Goli can identify the man as Eghbal without some doubts, so they track down Hamid (Mohamad Ali Elyasmehr), another former incarcerated man tortured by Peg Leg. Almost immediately, Hamid knows it’s Eghbal—he remembers the scars on the guard’s legs, and they match. Now it’s just a matter of what to do with him.

However serious It Was Just an Accident may sound, it also boasts darkly comic moments, such as when Vahid runs out of gas, and the group must push the van to the nearest station. Elsewhere, in a surreal display of corruption, two security guards demand a payoff for their silence, and if no one has cash, no problem; they carry a credit card terminal on them. Vahid faces a similar absurdity when Eghbal’s daughter calls her father’s phone. Eghbal’s wife has gone into labor, and so Vahid resolves to drive his torturer’s spouse and young daughter to the hospital. He even enlists the group to chip in on a tip and pastries for the nurse who helped—an Iranian tradition when a baby is born. Vahid is a decent man; unlike his former captors, he will not resort to inhumanity.

With that in mind, how will Vahid justify what may come next? Should they kill Eghbal? Should they demonstrate their moral superiority by letting him go? The climax unfolds at night in a ten-minute unbroken shot situated low to the ground, where Vahid and Shiva have tied their suspect. The van’s rear lights illuminate the scene in red, recalling the opening sequence in Goodfellas (1990). Like each scene in the film, there’s no accompanying score, just an unwavering commitment to this moment. Panahi’s direction is superb and immersive, making the 104-minute runtime race by, even if much of the film involves waiting and searching for confirmation. Finally, Vahid and Shiva, who have said goodbye to Hamid, Goli, and her future husband, resolve to let Eghbal go—or at least give him a fair chance to escape captivity. Their choice isn’t eye-for-an-eye vengeance; it denies viewers the catharsis of most Hollywood revenge films.

Panahi’s final provocative flourish arrives in the coda, where Vahid arranges a trousseau and manages several people coming and going from his house. Just then, Vahid hears the sounds of Eghbal’s prosthetic leg again. The sound seems to come and go as Panahi points the camera at Vahid’s back. He stands, frozen. The film never confirms the sound’s origin, though Vahid’s reaction is enough to convey its effect. The question I had was whether the sound harkens to Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart, a phantom brought about by, in this case, the inescapable trauma of Vahid’s detention and torture, not to mention his fear that Eghbal may have died, or worse, may return for him. Or perhaps the sound was real, so the question becomes whether Eghbal, as promised under duress, will leave Vahid alone. Then again, maybe his presence is a subtle threat; maybe Eghbal wants Vahid to know that he knows where he lives. The moment’s uneasiness and chilling possibilities linger well after the end credits begin to roll.

Even though Panahi has every reason to work through his imprisonment with anger and purge his personal and political frustrations with an artist’s poetic license in the form of satisfying revenge, he doesn’t. Panahi does something thornier and ambiguous, forgoing a tidy package or emotional conveniences for something more interpretive. Still, his characters speak out in their rage about “the system” created by cruel leaders and their enforcers, leaving a clear message to authoritarians who have deluded themselves into believing their rule will last or that they will never be held accountable for their actions. That’s a particularly resonant message, not only in Iran but anywhere a government attempts to strongarm its people or coerce them through fear. Inevitably, Panahi seems to say with It Was Just an Accident, the corrupt will face those they abused, and those in power should hope their victims show more humanity than they did.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review