A Separation

By Brian Eggert |

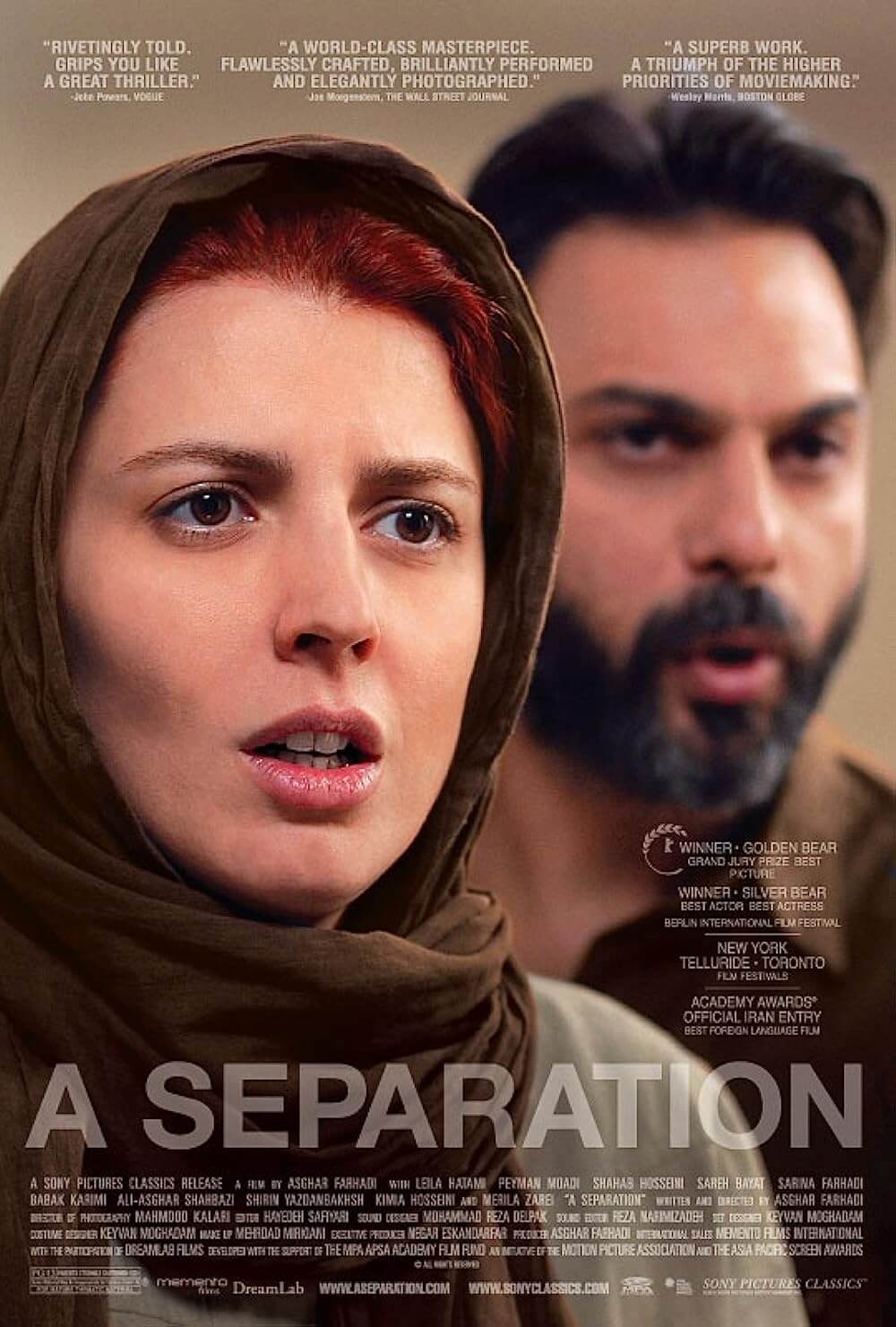

Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation could be mistaken as a drama about conditions specific to Iran that inhibit and prescribe. But what the film argues is that relationships between people are complicated, and matters of religion and gender inequality can exacerbate them. It’s a film more concerned with portraying the social realities of Iran rather than commenting on them. Released in 2011 to an incredible response throughout the international film community, thus making a name for Farhadi, his breakthrough effort is accessible without pandering to its audience. He has made a highly readable film, allowing viewers to interpret its intent. It is a cinematic chamber drama in which complex performances and unresolvable situations unfold in a few, mostly interior locations, lending everything a theatrical quality that never feels stagey. And like many a playwright from Harold Pinter to JC Lee, A Separation stimulates discussion about how the characters behave and how we feel about their choices. Is it a critique of Iran’s repressive society? Or does its portrait of the central couple, both secular and bourgeois, validate the religious values of the lower-class couple in the film? As most audiences would come to learn in the years since the film’s release, Farhadi’s work raises complicated questions in such a way that leaves them open, which might be why his almost imperceptible critiques, if that’s what they are, often slip by the rigid censorship of the Iranian government.

In the first scene, Farhadi drops the viewer into the middle of a long-brewing domestic dispute. A married, middle-class couple from Tehran sits before a judge. Our view of Nader and Simin (Peyman Moadi and Leila Hatami) is from the arbitrator’s perspective. They ask the judge for a divorce. Simin wants to leave the country for the sake of their 11-year-old daughter, Termeh (Sarina Farhadi), whom she doesn’t want to raise under “these circumstances.” There’s no clarification necessary. Everyone watching can imagine what it must be like for an Iranian woman with an education, not to mention an independent streak—hinted at by Simin’s dyed, artificially red hair emerging from under her obligatory scarf. “What circumstances?” asks the judge. Simin doesn’t answer directly, and Farhadi doesn’t make the subject of oppressed women an open discussion in his film—but it’s always there, informing the context of every scene and exacerbating every conflict. Simin has already prepared her family’s passports and paperwork, as we see in the title sequence of legal documents being scanned in a photocopier. Nader will not go along; his father (Ali-Asghar Shahbazi) has Alzheimer’s disease and needs someone to look after him. Still, Nader will not prevent Simin from leaving, but he also refuses to let Termeh go with her.

The situation becomes increasingly layered, as every scene unveils a new development in the drama. Farhadi, who also wrote the screenplay and produced A Separation, removes every unnecessary moment. Even early scenes, such as a passing conversation in a kitchen, become essential later, and one might need to rewatch the scene to notice how it was blocked. When the couple gets home from their meeting with the judge, Simin packs and leaves for her parents’ place with an unceremonious “Bye.” Her visa to leave the country will expire in 40 days, and she will use that time to convince her husband and daughter to go with her. In the meantime, Nader must hire a caretaker for his father while he’s at work. The working-class Razieh (Sareh Bayat), a devout woman accompanied by her young daughter (Kimia Hosseini), takes the job. But almost immediately, she has a problem when Nader’s father wets his pants, and Razieh must call an advisor to determine if her religion will allow her to care for the confused older man. There’s a moment of profound understanding between Razieh and her daughter when the girl says, “I won’t tell dad.” Razieh’s husband, Hodjat (Shahab Hosseini), is unemployed, pursued by his creditors, and known for his temper. She arranges for Hodjat to take over this post instead, but he never shows up as promised.

From the first moments on, A Separation has a style that might be described as realism, as cinematographer Mahmoud Kalari shoots the film in a harried way that follows heated encounters and situations as they unfurl. Kalari’s camera tracks the action, always peering through interior doorways and glass, often looking past out-of-focus objects and people in the foreground. Farhadi and Kalari enclose and limit the visual clarity on the screen, using frames within frames that suggest the sheer number of personal, social, and religious containers in which these characters must interact. Note the walls that consist of shelves with books—rectangles that create order through division inside of the thoroughly materialist home, which contrasts the undecorated walls of their class counterparts, Razieh and Hodjat, whose residence we see toward the end. In both homes, production designer Keyvan Moghaddam has created spaces drained of color, aside from Simin’s striking hair. The entire aesthetic of A Separation recalls Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives (1992), and that film’s similar relationship between its distressed formal approach and its strained relationships.

Farhadi continues to ratchet the complexity of the situation ever upward, shifting and testing our loyalties amid everyone involved. Farhadi employs what Godfrey Cheshire called the “‘glass onion’ effect,” in which the director’s audience watches “layer after layer of human mystery being peeled away.” The primary conflict arises when Nader comes home to find Razieh gone and his father on the floor, his arm twisted and tied to the bed. He scrambles to help his father and find out what happened, but the shaken man will not speak. Then, Razieh and her daughter return to the apartment, explaining, “Something came up.” There’s also money missing, Nader discovers, and he accuses the caretaker, who swears on “our martyrs” that she didn’t steal it. There are accusations and shouting. Nader tells her to leave his home, but Razieh continues to argue, and then he pushes her out of the door, apparently causing her to fall in the stairwell. Razieh is several months pregnant, and shortly after this encounter, she has a miscarriage. But there are questions. Did his push and her fall cause the miscarriage? Why did she leave the apartment and tie up the old man? Why did her husband never show up for the job?

In her book about Farhadi, Tina Hassannia wrote that his films walk the fine line between Iranian arthouse films, which are intended for international audiences, and those meant for Iranian cinemas. There are nuances throughout A Separation that haven’t been spelled out for Western viewers not familiar with, say, the precepts of the Islamic religion. Other Iranian filmmakers such as Majid Majidi (Children of Heaven, 1997) or Tahmineh Milani (Two Women, 1999) use more pronounced dramatic devices to comment on the social fabric of Iran. Consider how, in A Separation, the subtitles clarify Razieh’s reference to “our martyrs,” but the actual line mentions “Imam Hossein,” the martyr who died in the Battle of Karbala, and the son of the prophet Muhammad’s daughter Fatimah. There is no expository line to explain the reference or its significance. In this case, the subtitle translator sought to simplify the meaning, but Farhadi’s line as written was designed for its specificity. Similarly, he does not expound on the ins and outs of the Iranian justice system. When Nader finds himself next to Razieh and Hodjat in a small office, standing before another magistrate, he defends himself while standing next to his accuser. Likewise, he can just as easily file a complaint about Razieh for her treatment of his elderly father.

What’s also apparent here is that Farhadi is a wonderful director of actors. Once again, the performances never overemphasize a detail or gesture. Their actions feel reflexive and natural in the heat of the situation. Watch for their inbuilt responses to social policies dissuading interactions between men and women, especially touching between the unmarried. Realities such as this make lying a prerequisite for maintaining a sense of freedom, which becomes evident as Nader and those close to him begin answering questions, sometimes with lies. Nader downplays his culpability to the mediator. Razieh’s story doesn’t quite make sense either. Are they lying because their society forces them to, or is that our unfortunate assumption? The performances conceal the answers until the story forces them out. When we start receiving answers, the lies and betrayals raise A Separation to the level of high drama. Nader breaks promises to his daughter; Razieh falls back on her religion, despite her husband’s wishes; and the pointed decision required in the final scene—where Termeh must choose a parent—dramatizes our questions about the film’s intent: Is A Separation about Iran’s social realities, with Nader and Simin representative of a respective pro and con standpoint? Or is the film merely a tense drama?

What’s also apparent here is that Farhadi is a wonderful director of actors. Once again, the performances never overemphasize a detail or gesture. Their actions feel reflexive and natural in the heat of the situation. Watch for their inbuilt responses to social policies dissuading interactions between men and women, especially touching between the unmarried. Realities such as this make lying a prerequisite for maintaining a sense of freedom, which becomes evident as Nader and those close to him begin answering questions, sometimes with lies. Nader downplays his culpability to the mediator. Razieh’s story doesn’t quite make sense either. Are they lying because their society forces them to, or is that our unfortunate assumption? The performances conceal the answers until the story forces them out. When we start receiving answers, the lies and betrayals raise A Separation to the level of high drama. Nader breaks promises to his daughter; Razieh falls back on her religion, despite her husband’s wishes; and the pointed decision required in the final scene—where Termeh must choose a parent—dramatizes our questions about the film’s intent: Is A Separation about Iran’s social realities, with Nader and Simin representative of a respective pro and con standpoint? Or is the film merely a tense drama?

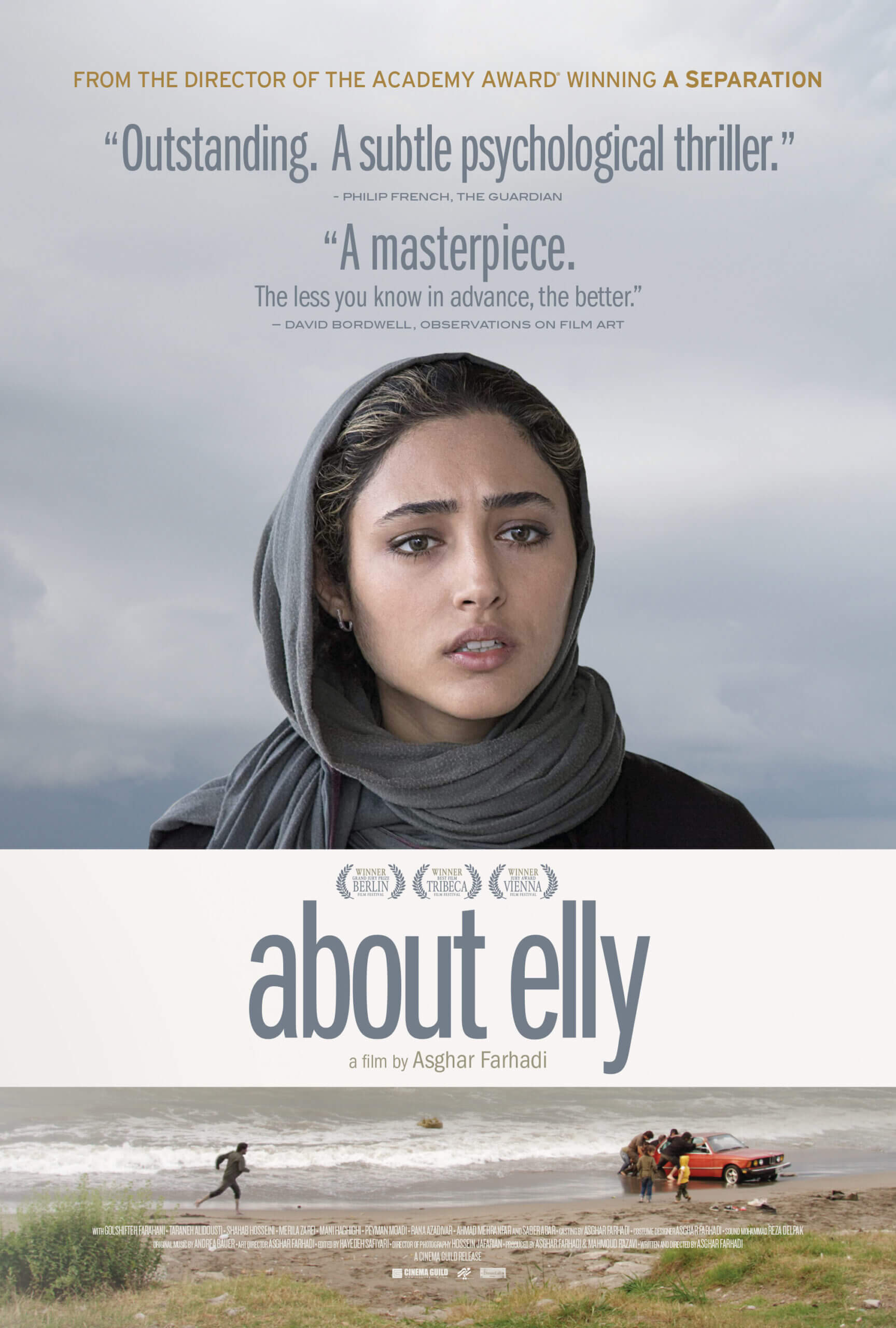

Farhadi made history when A Separation became the first Iranian film to win the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. It also won international awards for best film at the Berlin Film Festival, as well as honors from France’s César Awards and many other countries. The accolades made Farhadi a celebrity among cinéastes, ensuring distribution for his subsequent films including The Past (2013), The Salesman (2016), and his Spanish-language production Everybody Knows (2018), along with renewed interest in his earlier films, above all About Elly (2009). Born in 1972, Farhadi studied theater and stage direction before making films for Iranian television, which is perhaps why his films are so well structured and performed. In various interviews, Farhadi acknowledges that most of his influences are playwrights and not names from the pantheon of great Iranian filmmakers—and even when he’s talking about Iranian directors, he’s more apt to reference Dariush Mehrjui’s middle-class dramas than the more widely known arthouse films of Abbas Kiarostami. In the face of Farhadi’s theatrical inclinations, he savors intense expressions that could only be captured by a camera from within the middle of a scene. There’s a moment in a police station hallway where Termeh and Razieh’s daughters exchange a piercing glance that would never work on a stage.

Even as the situation in A Separation seems to confirm why Simin wants to leave Iran in the first place, Farhadi’s focus on domestic matters transcends national boundaries and brings Simin’s perspective into doubt—just as his film both aligns with and reveals faults in every character. Within these shifting loyalties, the film becomes almost interactive. In that sense, A Separation doesn’t feel like a “foreign” film but something terribly familiar in its arguments between husbands and wives, its clash of the upper classes and the lower, its look at religious devotion, and the tensions that arise amid such conflicts. The director’s talent for manipulating various pressures is captured in a scene where Razieh’s daughter plays with a gauge on the oxygen tank connected to Nader’s father; the jolts are immediate and shocking. Farhadi does something similar throughout the entire film, turning the gauge on his dramatic realism. Of course, there can be no blame for Razieh’s daughter because she is just a child. Similarly, there’s no unequivocal blame to be assigned throughout A Separation. Instead, Farhadi asks that we participate in the situation and search for answers—which he has not provided—within ourselves. What could be more universal than the human question of searching for what is right?

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review