If I Had Legs I’d Kick You

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published on October 22, 2025. It has been reposted for its expansion into more theaters on November 7, 2025.

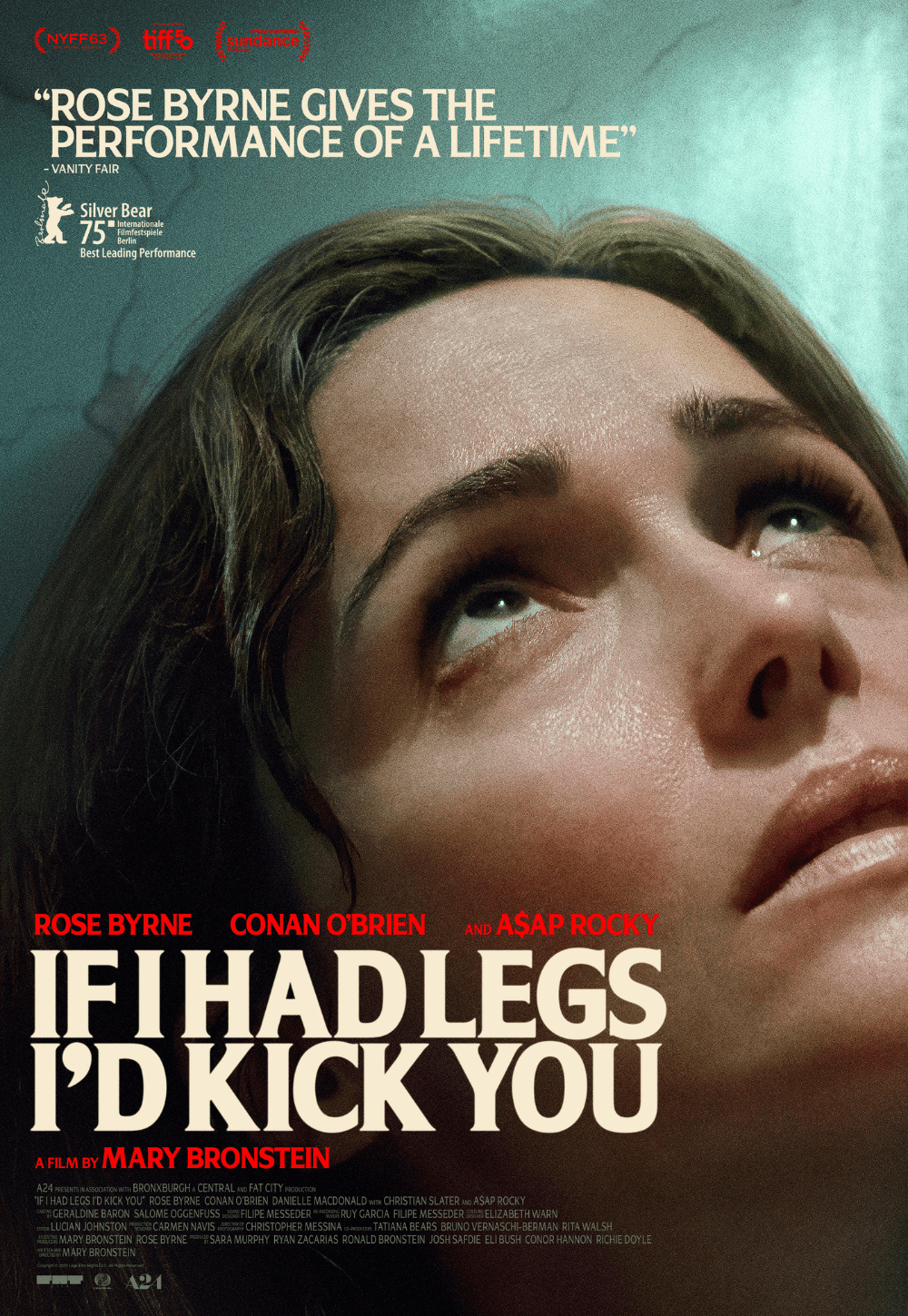

Motherhood is a hellhole in Mary Bronstein’s darkly funny If I Had Legs I’d Kick You. Linda, brilliantly played by Rose Byrne in the finest performance of her career, is the exhausted parent of a daughter with some vague chronic gastrointestinal malady. With her ship-captain husband away at sea, the fraught Linda juggles her daughter’s doctor appointments, her career as a therapist, and the contractors hired to repair their apartment after a burst pipe creates a hole in the ceiling, causing water to flood the space. Indeed, the figurative hellhole manifests in reality, creating a passage to an almost cosmic void that’s probably a projection of Linda’s unconscious mind—a vast, black nothing filled with pulsing stars and voices from Linda’s world, all of whom demand from her more than she can fulfill. The other hole in the film is plugged with a feeding tube into her daughter’s belly, home of the mysterious illness that causes so many complications in Linda’s life, ranging from getting her daughter to eat to finding a parking spot at the specialist clinic where the girl receives treatment. At a certain point, Linda must admit, “I’m one of those people who’s not supposed to be a mom.”

In the first scene of Bronstein’s film—her second, after her 2008 debut, Yeast—Linda’s daughter describes her as “stretchable” and sad. Linda counters, claiming she’s neither stretchable nor sad but says it with a wavering smile on her face and tears welling in her eyes. They’re talking to her daughter’s doctor (Bronstein), who’s increasingly frustrated with Linda’s inability to attend parental support group sessions and get her daughter’s weight to the goal of fifty pounds, at which point her tube can be removed. That’s not so easy when the girl refuses to eat even the cheese on a pizza. Bronstein based their dynamic on her experiences with motherhood and helping her child with an illness. However, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You is less about the mother-daughter relationship than the beleaguered experience of motherhood. In a bold yet effective choice, Bronstein keeps the daughter’s face hidden out of frame, while Byrne’s face remains in near-constant close-ups, capturing her tired eyes and understandably frantic moods.

In a sense, Linda is stretchable, pliable, and adaptable. But she can take only so much. She barely maintains her composure during the day, caring for her daughter and seeing patients at her cooperative-style office, the Center for Psychological Arts. At night, she lives in a motel with her daughter while the contractors fix the hole in her apartment—recalling the one in last year’s A Different Man, which was filled with rats and mold but also served as a symbol of the protagonist. The contractor has a funeral to attend, which means the work stops, maddeningly, for a week. She learns about this in a tense cell phone conversation, one of many in the film. Most are with her husband, played by Christian Slater, who remains a mere voice until the end and proves only somewhat as emotionally unavailable as he seems. He’s set to be gone for eight weeks, with five to go, leaving Linda with nothing but responsibilities. Carving out time for herself, Linda escapes into the night like a nocturnal creature, leaving her daughter alone in the motel room to sleep, while she goes out and chugs motel-cooler wine and smokes pot. One night, she returns home and dozes off to Flesh-Eating Mothers (1988), about crazed moms who eat their babies—a pointed choice.

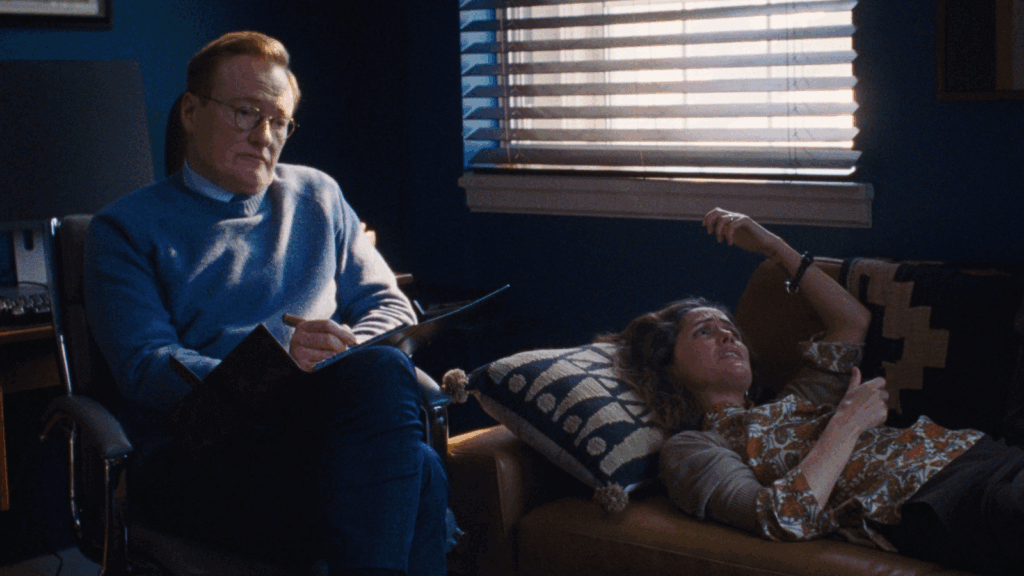

Besides self-medicating, she also sees a therapist a few doors down the hall from her office. Performed by Conan O’Brien with steely-eyed seriousness in a self-aware repurposing of his goofball late-night persona, the therapist listens to Linda compare their time together to a series of cliffs with no end. I imagine that having a fellow therapist as a patient comes with drawbacks, and sure enough, Linda cuts into him, complaining of “no thread” to their sessions. In her defense, he seems unwilling to offer much, ignoring her pleas to “tell me what to do.” Then again, he tries to maintain professional boundaries, which become ever more flimsy as Linda’s indecision and stress levels rise to a rolling boil. Moreover, she seems to transfer her relationship with her absent husband onto him, treating him less like her therapist than a friend to whom she describes her dreams and frustrations, and at one point muttering “I love you” as he leaves the room. Still, he cuts her loose, prefacing the decision with a horrifying story involving rat experiments and a guillotine.

Her therapist isn’t the only temporary man in her life. There’s also James, the motel superintendent, played by A$AP Rocky, who stars in his second A24 production this year after Spike Lee’s Highest 2 Lowest. James strikes up a tentative friendship with Linda, who doesn’t really allow him to get close. He’s unfailingly kind to her; she’s nothing short of inconsiderate to him. She even abandons him in her apartment after he falls through the hole and breaks his leg. Some strange things happen in that apartment during her periodic visits, including an abrupt UFO-like stream of light and firefly-like glimmers that prompt her to ask, “Mom?” Linda doesn’t talk about her mother; presumably, she’s dead. Was she a good mother, and perhaps Linda sees herself as a failure by comparison? Bronstein leaves the detail ambiguous, just as she crops Linda’s daughter out of each frame and doesn’t show her husband’s face until the finale.

The film is laser-focused on Byrne. Watching Byrne perform her scenes, I kept thinking about how I hadn’t seen a performance so committed and unruly since Gena Rowlands in A Woman Under the Influence (1974). Yes, she’s that good. Byrne’s relentlessly distressed character endures much but also amplifies everyday bad luck to a state of crisis. She’s probably most well known for her comedic work in Bridesmaids (2011) and Neighbors (2014), or the occasional horror yarn such as 28 Weeks Later (2007) and the Insidious movies. With Bronstein, Byrne creates an unforgettable performance that, aside from Linda’s under-the-influence interludes, finds her actorly dial turned up to eleven. And while a character like this could grate on the viewer or risk incurring the audience’s judgment, Byrne lends a humanity to the role that makes her sympathetic, even in the character’s worst moments.

Bronstein also brings her script to life by drawing influence from her occasional collaborators, Josh and Bennie Safdie, who starred in Yeast. She’s also married to Ronald Bronstein, who has worked as co-writer and editor on the Safdies’ Daddy Longlegs (2009), Heaven Knows What (2014), Good Time (2017), and Uncut Gems (2019). He serves as producer here. Just as the Safdies’ films feel like cinematic panic attacks, Bronstein’s effort remains urgently attuned to Linda’s emotional state through furiously mobile camerawork by cinematographer Christopher Messina, another Safdie collaborator. And given how besieged Linda is, the film takes on a surreal quality through her eyes. Consider, for example, when Linda finally gives in to her daughter’s incessant demands for a pet hamster. During a car ride when another driver rear-ends Linda’s vehicle, the hamster becomes a feral beast hilariously rendered onscreen with a combination of puppetry and CGI.

During a particularly frenzied sequence, one of Linda’s patients (Danielle Macdonald), who’s suffering from postpartum depression, leaves her crying infant in her office. Linda’s next patient, Stephen (Daniel Zolghadri)—a rude, fixated young man—arrives only to find his start time with Linda has been delayed. Crying baby in hand, Linda solicits her colleague’s help. After attempting to slam a door in her face, O’Brien’s character agrees to assist, albeit begrudgingly. “Make a choice,” he tells Stephen, suggesting he either leave or wait down the hall. Linda takes this lesson and applies it to her situation, eventually making a choice about her daughter’s impossible situation. Whether it’s the right or wrong one, Bronstein never confirms—although the nightmarish and squirmy outcome is among the most disgusting things I’ve seen in any film this year. Regardless, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You acknowledges that mothers face endless pressure to make the right decisions. They’re blamed when things go wrong, meaning there’s unfathomable, unachievable pressure to do everything right. Sometimes, there’s nothing to do but scream into a pillow.

Bronstein’s film belongs on a shortlist alongside other recent films about motherhood, all of which convey the unflinching, life-sucking, sanity-testing experience. Among them is Marielle Heller’s Nightbitch (2024), in which being a mother prompts Amy Adams’ character to transform into an unleashed animal at night. If I Had Legs I’d Kick You is a vastly superior film that delivers a nerve-shattering, anxiety-riddled two hours with a haunting, propulsive score and magnificent central performance, even while prompting nervous laughter and discomfort. Some may recoil from the experience; I leaned in, consumed by Linda’s subjective perspective and dreamlike mental breaks. Bronstein commands a film that may play like a horror movie to some, or like the blackest of comedies for others. However it registers, it’s not something that can be ignored or processed passively. Bronstein and Byrne make us feel every desperate, tightly wound emotion in a film that boasts one of the year’s best performances and biggest surprises.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review