I Care a Lot

By Brian Eggert |

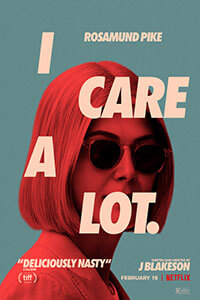

I Care a Lot makes the viewer choose: Will you place your sympathies with a professional legal guardian who milks a system loophole to drain the bank accounts of elderly folks, or will it be a human trafficker from the Russian mafia? They’re both despicable in their respective ways, ruthless in their exploitation of others, and self-aware about their criminality. Either choice is wrong, morally speaking. Of course, no rule says that an audience must align with one character or another; sometimes, the most challenging and unconventional films leave us no one to root for. But most stories feature a protagonist of some kind who, regardless of their misdeeds, earns some scrap of compassion. Writer-director J Blakeson’s latest is exceptional in that we’re lucky if we can empathize with anyone. As he reminds us in his film’s opening narration, uttered by Marla Grayson, confidently played by Rosamund Pike, “There’s no such thing as good people.” In I Care a Lot, that’s a gross understatement.

Pike is excellent as Marla, who starts out with a well-paying enterprise of selecting senior citizens for guardianship. Marla’s ideal candidate has specific demographics: they’re young enough to last a while; they have no family to complain about the exploitative situation; they have good credit, and a financial nest egg to draw from; and enough assets to sell at auction. After vetting a potential client, Marla bribes a corrupt doctor (Alicia Witt) to declare the prospect unable to care for themselves. A clueless judge (Isiah Whitlock Jr.) signs off and appoints Marla as a legal guardian. At this point, a crooked care facility manager (Damian Young) takes the poor old sap into his establishment. Marla then proceeds to sell her victim’s assets to pay her excessive fees and live the good life. This happens more than you might want to think about in the real world, and actual accounts and exposés inspired Blakeson’s script. It’s a lucrative scam for Marla, and she appears to live a very comfortable life, but it becomes more complicated with her latest client, Jennifer Peterson (Dianne Wiest).

Although Marla’s personal and professional partner, Fran (Eiza González), describes their new mark as a “cherry” for her loaded bank accounts and a lovely home filled with antiques, they quickly discover Jennifer isn’t what she seems. Outwardly, she’s an unmarried retiree with no apparent family ties; however, her safety deposit box with loose, unclaimed diamonds suggests something shady. As it turns out, Jennifer has an off-the-books son, Roman (Peter Dinklage), the aforementioned Russian gangster. And he wants his mother out of the care facility that Marla has arranged. But in a prologue, we’ve already seen what happens when a desperate son (Macon Blair) tries to force a broken legal system to bend to his will (hint: it doesn’t work out). Worse, Marla wants to protect her investment, and her criminal ingenuity is slippery enough to outmaneuver Roman’s intimidation tactics.

Blakeson, who already made a superb kidnapping thriller with 2010’s The Disappearance of Alice Creed, organizes his film in a four-act structure, albeit with shifting perspectives. The first act establishes I Care a Lot from Marla’s subjectivity, signaled by her narration and stated ambition to achieve financial freedom—not only to live the comfortable upper-middle-class life she already has, but to be able to wield money as a weapon. Once she takes on Jennifer, the second act wrinkle introduces Roman and the legal system that will prevent him from rescuing his mother from Marla’s clutches. The second and third acts align with Roman and his gangster cohorts, who attempt to reacquire his mother from Marla—first with his attorney (Chris Messina, a smooth performance behind a couple of ridiculous suits) and then with violence. But Marla is frustratingly defiant of their attempts, suggesting the link between her form of criminality and theirs. The final act resituates the story from Marla’s perspective, as she outsmarts Roman and, eventually, joins forces with him to form a criminal corporation.

Blakeson, who already made a superb kidnapping thriller with 2010’s The Disappearance of Alice Creed, organizes his film in a four-act structure, albeit with shifting perspectives. The first act establishes I Care a Lot from Marla’s subjectivity, signaled by her narration and stated ambition to achieve financial freedom—not only to live the comfortable upper-middle-class life she already has, but to be able to wield money as a weapon. Once she takes on Jennifer, the second act wrinkle introduces Roman and the legal system that will prevent him from rescuing his mother from Marla’s clutches. The second and third acts align with Roman and his gangster cohorts, who attempt to reacquire his mother from Marla—first with his attorney (Chris Messina, a smooth performance behind a couple of ridiculous suits) and then with violence. But Marla is frustratingly defiant of their attempts, suggesting the link between her form of criminality and theirs. The final act resituates the story from Marla’s perspective, as she outsmarts Roman and, eventually, joins forces with him to form a criminal corporation.

Unfortunately, Blakeson makes a miscalculation by leaving us with an entire cast of despicable characters, but not in the way that Martin Scorsese explored gangsterism in Goodfellas (1990) and Casino (1995) or dodgy stockbrokers in The Wolf of Wall Street (2013). Scorsese’s protagonists in these films start as average nobodies who want a taste of the good life. In their progressively more criminal moves to attain money and power, they sacrifice their humanity along the way, making the story a tragedy. At the same time, he makes these lifestyles look desirable, allowing his audience to see the appeal, even as we judge for ourselves the morally reprehensible behavior on display. Alternatively, Blakeson starts Marla as a well-to-do and ambitious character; he offers no backstory or dramatic arc of gradual moral decay. She begins the story as a monster, and she ends the story as an even bigger monster, which makes it strange that Blakeson would accompany Marla’s scheming with hip music that suggests we should be having “fun”—her word—watching her work. But her character proves so empty-hearted that we’d almost prefer it if Roman, a horrific person, defeats Marla, if only because of how much time Blakeson spends sympathizing with his mission to free his mother. Soon enough, it becomes apparent that Blakeson has chosen to rob the viewer of anyone worthy of our investment. Worse, Marla has no epiphany, does not change her ways, and learns nothing from the events.

Doubtless, that’s Blakeson’s point. But he makes it without showing how Marla became this way. What has turned her into such a ruthless person? Did she come from a poor family, and so she’s desperate to avoid that life? Blakeson, I think, would prefer not to humanize her because it’s easier to despise someone than to realize human beings are complicated, as Scorsese does. And, if the scene in which Marla and Fran dispose of a body in the glow of red brake lights at night is any indication, Blakeson clearly had Goodfellas on his mind when he was making I Care a Lot. The film is full of zippy energy and intense encounters, similar to those in Scorsese’s film. But at least Henry Hill expressed some regret over where he ended up, unable to get a decent plate of pasta like a schnook. Marla is incapable of remorse. So why would we care what happens to her? Pike’s performance goes a long way to keep the viewer invested; she’s icy and confident, defined by her vape pen, sharp bob, and stilettos. Once more, she’s playing a criminal genius reminiscent of her role in Gone Girl (2014), although Amy Dunne’s manipulation at least has a motivation beyond simply getting richer. There’s a single, sharklike dimension to Marla, and Pike captures that, to be sure. But it’s contained in a heartless story that keeps us at a remove. Sure, we empathize with Jennifer and want to see her freed from the care facility, and Wiest is terrific in her few scenes, though the character is little more than a pawn.

I Care a Lot isn’t a film about the criminals you love to hate—it’s about the criminals you just plain hate. Blakeson’s script doesn’t help matters with bookend scenes of Marla expressing her cliché worldview: “Playing fair is a joke created by rich people to keep the rest of us poor,” she says. “So what you have to decide is, are you a lion or a lamb? Are you a predator or prey?” This hackneyed message, along with other on-the-nose narration, suggests Blakeson could think of no story more representative of the American Way. Fair enough. The reality of exploitative legal guardianship is indeed disturbing, and the film shines a light on it. But unlike recent riffs on Goodfellas with women at the center (see I, Tonya or Hustlers or Buffaloed), this one doesn’t exist in a fog of complex emotional and moral compromises. It drops the viewer into a black pit, where we feel nothing but disdain for the characters and situations, and we come away having gained little.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review