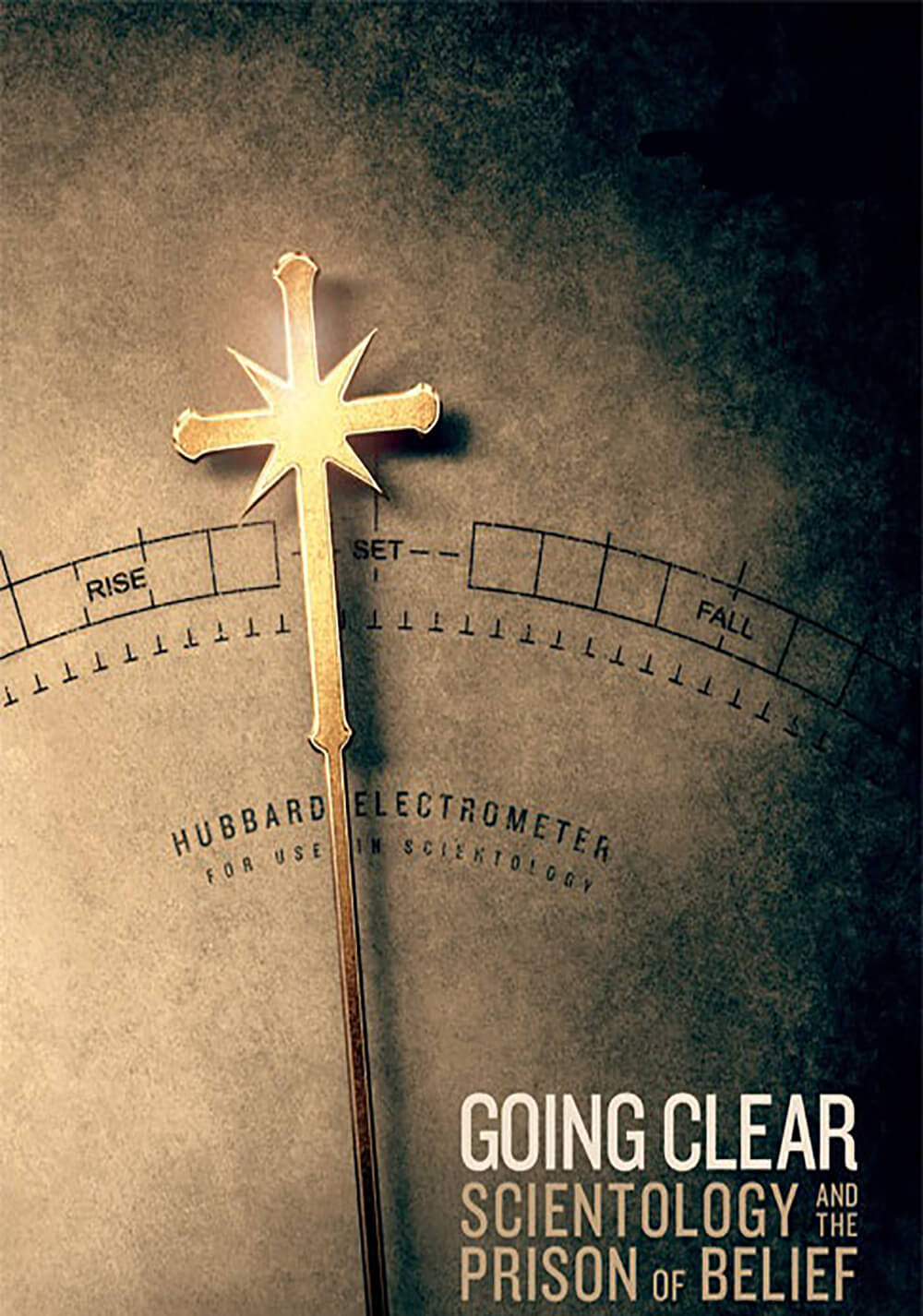

Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief

By Brian Eggert |

As Bill Maher said in his documentary Religulous, “Faith means making a virtue out of not thinking.” Alex Gibney’s documentary Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief considers its subject in a discerning investigation, and by extension, reflects on the dangers of faith. Based on Lawrence Wright’s 2013 nonfiction bestseller, the film debuted at the Sundance Film Festival in 2015 under some concern that it wouldn’t make the screen. The notoriously litigious so-called religion has been known to sue naysayers for libel and slander; both Wright and the film’s producer Sheila Nevins claim they received countless threats of suit from lawyers representing The Church of Scientology. But rather than distribute the film into theaters, where it has received intermittent distribution, the filmmakers released the doc on HBO, where it’s likely to reach a wider audience. Indeed, a reported 1.7 million viewers watched Gibney’s doc on its original air date, and those figures do not include subsequent on-demand viewings or reruns.

Accustomed to taking incredibly complex ideas and reducing them down to their simplest parts, but without losing any of the detail, Gibley is a prolific and talented documentarian. Among others, he made Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005), Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God (2012), and We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks (2013). Gibney’s very well-argued, very human approach to Going Clear draws much from Wright’s book, while understandably leaving out much of the 400-plus-page exposé for the film’s two-hour runtime. Nevertheless, his screentime consists of largely on-camera testimonies from ex-Scientologists and footage from the religion’s various rallies and celebrations, all of which must be seen to be believed. Whatever you may have read about Scientology does not compare to seeing videos of their rallies, which have eerie similarities to Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda piece Triumph of the Will (1935).

In a sharp assessment of Scientology’s history, spiritual and financial drives, and hierarchical organization, Gibney begins by delving into the life of founder L. Ron Hubbard. Author of over 1,000 published books, mostly science-fiction, Hubbard fabricated and elaborated upon his otherwise embarrassing military history. He turned his life into a heroic record used to impress his second wife, Sara Northrup Hollister, whose letters paint an unflattering portrait of a quite possibly unbalanced individual determined to transform his gift for fiction into a flawless financial plan. Archival footage of Hubbard shows a charismatic, portentous figure who, as Gibney suggests, gradually begins to believe his own stories. In a way, Hubbard’s later years became tragic, as he had long resisted psychoanalysis or psychotherapy, but in a final letter, he reaches out to the Veterans Administration for analysis and asks, “Will you please help me?” Best of all, footage of Hubbard reinforces how brilliantly informed Philip Seymour Hoffman’s performance was as the fictional cult leader in Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master (2012).

Amid familiar stories about John Travolta and Tom Cruise’s prolonged, possibly fear-induced association with the organization, Going Clear‘s interviewees, some of whom were very high up in the church’s leadership, though they’ve all since been denounced by the church, put themselves in the line of fire to speak out. Witnesses Mark “Marty” Rathbun, Mike Rinder, Sylvia “Spanky” Taylor, Hana Eltringham Whitfield, and Oscar-winning director Paul Haggis all discuss their many years as members. Each describes how the process of excising their personal demons through “auditing” resulted in a feeling of euphoria, how each stage of development created the illusion of growth and progress, and how they felt when, after reaching a particular stage, they learned Hubbard’s out-there origin story for the universe. Whether the benefits of auditing serve as a therapy of sorts or just an illusory cure, what comes next is what usually sends members packing. Eyebrows raise at stories of Xenu, the tyrant ruler of the “Galactic Confederacy,” and how past trauma results from spirits called “thetans,” which originated when Xenu dropped soul-filled atomic bombs into volcanoes millions of years ago.

What seems impossible and outlandish at first becomes downright unsettling when witnesses describe their feelings of belonging to a cult, and how the group reacts with threats when former members want to speak out. After Hubbard dies, the church carries on under paranoid leader David Miscavige, who allegedly orders the surveillance, threats, and detainment of the church’s enemies, both internal and external to the organization, some of who are either brainwashed or remain afraid to leave because of the consequences. Elsewhere, there’s talk of Scientology’s Sea Organization sailing international waters to avoid having to answer to anyone, and their “Gold Base” in Riverside County, CA, which contains two double-wide trailers known as “the hole” for detainment. Most shameful is the segment about how Miscavige and company bullied the IRS into forgiving Scientology their $1 billion in tax debt by allowing them religious status, therefore granting them any number of protections and freedoms under the First Amendment.

Underneath the entire film dwells the question of whether the church’s members actually believe Hubbard’s sci-fi mysticism as doctrine, or if they’ve simply claimed to buy into this mumbo-jumbo because it affords them untold protection and tax benefits. Some witnesses attest to how fully they believed in what Scientology was selling, and how it seemed to truly help them. These people must have believed the benefits of endless auditing and thetan expulsion; at least, that’s what they believe at first. Witness Sara Goldberg, who achieved Operating Thetan Level 8 (the highest level available to Scientologists), still yearns for more—and the consequence of her speaking out is that her family has since been instructed by the church not to speak to her, as she’s a “suppressive person.” Then again, Gibney seems to argue that a large portion of the church’s slim 50,000 members has remained for one of two reasons: 1) they fear reprisals if they leave, and 2) the financial benefits are too great. After all, the supposed non-profit organization reports hundreds of millions each quarter and owns billions in real estate the world over.

If nothing else, Gibney could be accused of not taking Going Clear far enough; meaning, there is some discussion of “the prison of belief” that defines not only Scientology but all religions. Whether or not Scientology represents a bona fide religion seems to be only part of the issue, according to interviewees like Haggis. As Maher said in his aforementioned documentary, “We shouldn’t get too hung up on the word religion. The bottom line is whether people think and act rationally or not. And whenever they organize their lives around something that could best be described as groundless, bad things happen.” Gibney’s documentary outlines that bad things are happening around Scientology. But since the dawn of humankind, people have done horrible things in the name of all religions. Consider the 9/11 attacks, the Spanish Inquisition, the slaughter of thousands in the Crusades, or any number of terrorist attacks reported in recent headlines—to name just a few atrocities carried out under all-consuming beliefs and the logic that my religion is better than yours. Gibney may not attribute Scientology to genocide or mass killings, but accusations of propaganda, torture, paranoia, tax evasion, and fear-mongering will suffice.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review