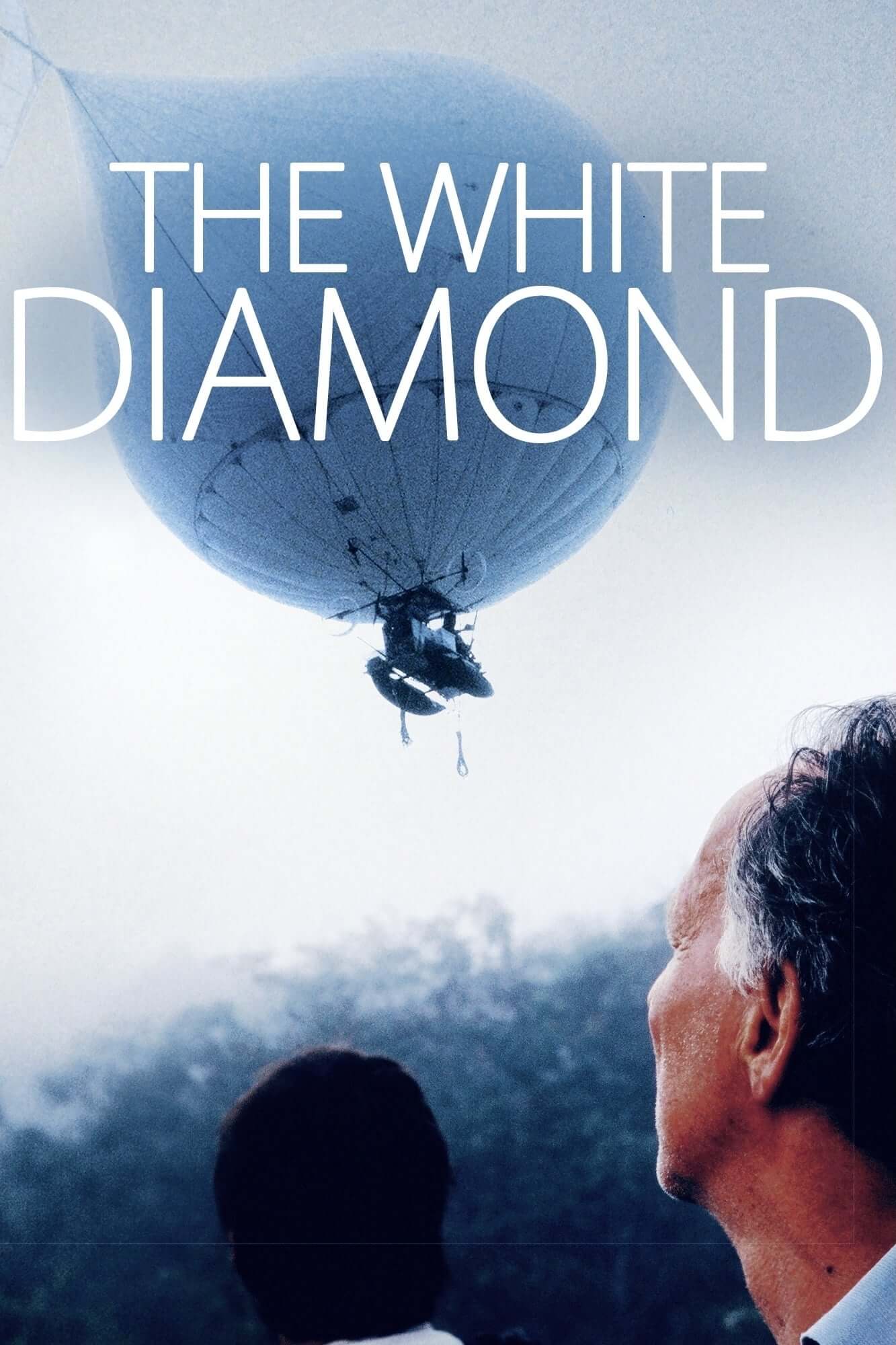

The White Diamond

By Brian Eggert |

Werner Herzog’s documentary The White Diamond contains moments both fabricated and rehearsed in the name of truth. Herzog often establishes situations that may not have occurred naturally; he impels them into existence, recreates them, or modifies them to fit his vision. Most of these artificial or reproduced moments create a thematic association between the documentary subject at hand and his formative past experiences shooting Aguirre, The Wrath of God (1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982)—during which the German filmmaker was branded both psychologically and artistically by his confrontation with Nature. But none such alterations or flourishes to reality betray what are otherwise called truth; they elucidate the truth of Herzog’s reality. It is the truth that Nature is harsh and unforgiving, and those who venture into Nature without the appropriate apprehensions represent Holy Fools—figures that critic Amos Vogel describes as closer to truth for their unhinged willingness to face the unimaginable.

However contrary to documentary ethics his expressive and poetic approach may seem, to be fair, Herzog does not call his films documentaries at all—he describes his fiction and nonfiction titles alike as “films,” without further qualifiers. From Grizzly Man (2005) to Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (20o9), his films contain images of incredible and horrible beauty in Nature, and they feature Holy Fools trying to understand it. In The White Diamond, Herzog follows Dr. Graham Dorrington, an aeronautical engineer constructing an air balloon ship that will allow him to hover over and study the rain forest canopy at the edge of the giant Kaieteur Falls in Guyana, South America. Dr. Dorrington had attempted the same experiment before, in 1993, but the attempt resulted in the death of his cinematographer, Dieter Plage. Dorrington had long felt responsible for the tragedy, until he finally attempted it again in 2004.

Released on the festival circuit in 2004 and then an expanded (but still quite limited) theatrical release in 2005, The White Diamond received a slew of mostly positive reviews. Even so, the film remains among Herzog’s most underseen and underappreciated documentaries, and a superb example of his most persistent themes: Holy Fools facing Nature. Dorrington admits that he’s “confronting chaos” in his flight by taking such a delicate airship into the harsh conditions around the falls, and therein facing the sublime, the unknowable and unconventionally alluring aspect of Nature. The shots around Kaieteur Falls showcase the glorious, powerful rush of water that risks swallowing Dorrington’s delicate airship into the vacuum around it. Herzog’s camera revels in the contrasts: the beauty of the surrounding forest and its wildlife, all split by the presence of the river’s current. It seems as though Dorrington must be mad to think he can drift over the falls in an airship and avoid a disaster from something so small as a fluctuation in wind or air pressure.

The film features on-the-scene footage and Herzog’s interviews, which mine his characters through observation. In an early scene, Dorrington talks about the limitless possibility of dreams and accomplishing them. He plays a role for the camera, acting enthusiastic and informative; but he’s also exposed and fragile, quite evidently so. His eyes connect directly to the camera during his performance, and there’s a desperation behind them. After Dorrington finishes his talk, he displays an awkwardness for the last few seconds of the shot, revealing his vulnerability. Herzog frequently lingers on moments like this, allowing his camera to run long after his interview subject has finished their statement; rather than ask an additional question, Herzog finds a degree of vulnerability in his subjects. Elsewhere, he searches for truth in non-sequitur scenes that seem to occur naturally, even randomly. His roaming camera finds strange people and allows them to talk, hoping to grasp their perspective in spite of the moment being a detour in the progression of Dorrington’s quest. When his camera wanders around Dorrington’s balloon as it fills with helium, he finds an odd local in a blow-up chair who reflects on the airship, seemingly without being prompted: “There is the balloon, just floating around, aimlessly… This is like a diamond. A nice big diamond… I dedicate this to my mom, somewhere in Spain.”

The film features on-the-scene footage and Herzog’s interviews, which mine his characters through observation. In an early scene, Dorrington talks about the limitless possibility of dreams and accomplishing them. He plays a role for the camera, acting enthusiastic and informative; but he’s also exposed and fragile, quite evidently so. His eyes connect directly to the camera during his performance, and there’s a desperation behind them. After Dorrington finishes his talk, he displays an awkwardness for the last few seconds of the shot, revealing his vulnerability. Herzog frequently lingers on moments like this, allowing his camera to run long after his interview subject has finished their statement; rather than ask an additional question, Herzog finds a degree of vulnerability in his subjects. Elsewhere, he searches for truth in non-sequitur scenes that seem to occur naturally, even randomly. His roaming camera finds strange people and allows them to talk, hoping to grasp their perspective in spite of the moment being a detour in the progression of Dorrington’s quest. When his camera wanders around Dorrington’s balloon as it fills with helium, he finds an odd local in a blow-up chair who reflects on the airship, seemingly without being prompted: “There is the balloon, just floating around, aimlessly… This is like a diamond. A nice big diamond… I dedicate this to my mom, somewhere in Spain.”

Other scenes prove less genuine. Herzog openly confronts Dr. Dorrington’s refusal to test his airship without risking another cinematographer, believing the test should be caught on camera regardless of the risk involved. Dorrington hesitates because of Plage’s death. Now appearing onscreen for the first time in the film, Herzog himself questions Dr. Dorrington’s sense of scientific responsibility: “There are dignified stupidities. There are heroic stupidities. And there is such a thing as stupid stupidities. And that would be a stupid stupidity, not having a camera onboard.” To resolve the situation, Herzog himself mans the camera and joins the flight as Dr. Dorrington faces the sublime. But this argument between Herzog and Dorrington about stupidity and the lack of a cinematographer was “completely faked” according to Dorrington, albeit following an actual discussion. The scene demonstrates Herzog’s approach and his willingness to accentuate reality for truth, allowing for creative choices that go against typical ideas of a documentary.

Indeed, film philosopher David LaRocca notes that Herzog believes in “truth through fabrication, evidence-based improvisation, and shrewd consolidation, by creating gripping intellectual and emotional arcs where there would otherwise be just notes or merely suggestions of them.” As long as such creativity results in what Herzog sees as the truth of a scene, the method does not matter, even if his choices bend the documentary’s limits as a subdivision of nonfiction film. The faked moment between Dorrington and the director was compelled by Herzog’s deep subjectivity. He shows Dr. Dorrington as a manic-eyed obsessive who insists on risking his life, even after the death of his former cinematographer, to get images of sublime Nature. Herzog’s subjective perspective informs his understanding of Dorrington’s sometimes reckless need to fulfill his experiment as he, too, had an unbridled need to fulfill his objective on the aforementioned films, Aguirre, The Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo—two productions on which Herzog engaged in perilous dangers to capture unthinkable footage.

Of course, The White Diamond contains scene after scene of majestic imagery around Kaieteur Falls, but Herzog never allows his camera’s gaze to dispel Nature. Consider a scene in which Herzog’s cameraman climbs down to look into an unexplored and inaccessible cave behind the falls. The director refuses to show the footage because, as a local says, “I don’t think you should publish it… the whole essence of our culture tends to die away [when the mystery is exposed on camera].” Herzog respects this and preserves the poetic truth of Nature’s sublimity through its mystery. Instead, he offers an extended sequence in which white-tipped swifts swarm in the sky and then dive into the blackness behind the falls, into a place unexplored by humans. As the swifts’ neverending current disappears into the unknown, the sequence is set to a haunting folk hymn that booms with mysterious harmonies, and the pairing of sound and image suggests the equal measures of beauty and curiosity.

Of course, The White Diamond contains scene after scene of majestic imagery around Kaieteur Falls, but Herzog never allows his camera’s gaze to dispel Nature. Consider a scene in which Herzog’s cameraman climbs down to look into an unexplored and inaccessible cave behind the falls. The director refuses to show the footage because, as a local says, “I don’t think you should publish it… the whole essence of our culture tends to die away [when the mystery is exposed on camera].” Herzog respects this and preserves the poetic truth of Nature’s sublimity through its mystery. Instead, he offers an extended sequence in which white-tipped swifts swarm in the sky and then dive into the blackness behind the falls, into a place unexplored by humans. As the swifts’ neverending current disappears into the unknown, the sequence is set to a haunting folk hymn that booms with mysterious harmonies, and the pairing of sound and image suggests the equal measures of beauty and curiosity.

Herzog balances what is shown and not shown, what is real and unreal in The White Diamond. Though documentaries often purport factual accounts, facts do not interest Herzog. The value of cinema—documentaries and fiction films alike—resides in expressive and aesthetic representations from which some measure of understanding or truth is derived. In both fiction and nonfiction, Herzog is a storyteller first. He believes in the power of cinema to create a greater understanding of the world, and for him, wisdom does not derive from facts but trying to see the world from other perspectives. “Truth illuminates,” he often says, and reveals “the ecstatic truth” about human beings. When The White Diamond finally captures the success of Dorrington’s scientific and personal mission, it illuminates how humanity is no different than a delicate piece of human technology standing before the transcendence of Nature. By association, the film also illuminates Herzog’s experiences and cinematic preoccupations in a perfect metaphor.

Sources:

Aimes, Eric. “The Case of Herzog Re-Opened.” A Companion to Werner Herzog. West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2012, pp. 393-414.

Burke, Edmund. “A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful.” Aesthetics: A Comprehensive Anthology, Ed. Steven M. Cahn and Aaron Meskin. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2008, 113-122.

Cagle, Chris. “Postclassical Nonfiction: Narration in the Contemporary Documentary.” Cinema Journal. Vol. 52 Issue 1. 2012, pp.45-65.

Cronin, Paul. Herzog on Herzog. London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 2002.

Herzog, Werner. Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the Making of ‘Fitzcarraldo’. Ecco, Reprint Edition, 2010.

LaRocca, David. “‘Profoundly Unreconciled to Nature’: Ecstatic Truth and the Humanistic Sublime in Werner Herzog’s War Films.” The Philosophy of War Films, David (ed. and introd.) LaRocca, UP of Kentucky, 2014, pp. 437-482.

Prager, Brad. The Cinema of Werner Herzog: Aesthetic Ecstasy and Truth. London: Columbia University Press, 2007.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review