Reader's Choice

Frailty

By Brian Eggert |

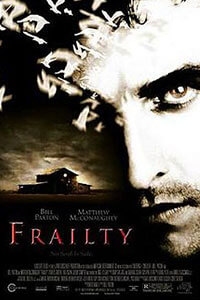

For most of its runtime, Frailty contains a tenuousness worthy of its title. The film is about a single father who believes he was enlisted by an angel to destroy demons hiding among us. He tells his two young boys, ages seven and ten, about the plan, and recruits them to ensnare and dispose of his victims. The uncertainty about whether his claims are real or not is terrifying. As viewers, we cannot help but make connections to real-life killers who claimed God told them to commit their horrible crimes. Serial killers and disturbed individuals who have done the unthinkable in the name of religious forces appear in the news with shocking regularity. But we also question whether the father, credited as “Dad” and played by Bill Paxton, actually met an angel. After all, this is a horror movie, and stranger things have happened in the genre. In the final scenes of Frailty, however, Paxton, who also makes his directorial debut with the film, betrays the ambiguity and confirms our suspicions one way or the other. It’s a film that comes close to disturbing brilliance but instead answers its essential questions.

The screenplay by Brent Hanley uses a framing device that follows a ragged-looking Matthew McConaughey into the office of Agent Wesley Doyle (Powers Boothe) at FBI headquarters in Dallas. He claims to know the identity of the “God’s Hand” killer. His account takes us back to 1979 in Thurman, Texas, the summer when Dad told young Fenton and Adam (Matthew O’Leary and Jeremy Sumpter) that an angel visited him in the night. We see what Dad sees, namely a shimmering trophy, but we do not hear an angel’s voice or witness the instructions. When he wakes up his two boys to tell them the news, he describes his mission in terms any child would understand. He calls them a “family of superheroes” armed with “magical weapons” in the form of a metal pipe, leather work gloves, and an axe. The youngest, Adam, believes his father. Fenton only believes that his father has gone mad. “Maybe you’re not right in the head,” he says. But Fenton’s doubts will get him into trouble later.

Frailty involves several sequences where Dad either kills a victim in front of his children or encourages them to take part. It’s not something we usually see in movies, even horror movies, and it’s shocking, if also mercifully free of blood and gore. “Destroying demons is a good thing,” their father assures. “Killing people is bad.” Paxton never reveals their demon form, though, if indeed it exists. He shows Dad touching his frightened, bound, and gagged victims with a bare hand and reacting with a jolt, after which he claims to have seen the demon’s sins. Later, Adam makes the same claim. But when Fenton touches his father’s victims, he doesn’t see anything. Fenton’s persistent doubts lead to a sense of betrayal and eventually punishment. It’s all the more tragic because the early scenes establish Dad as a loving and considerate father. He’s a blue-collar mechanic who isn’t above helping his boys with their homework or resorting to silliness to make them laugh. It’s not until he learns about “God’s special purpose” and the impending Judgment Day that he begins to distort into some kind of monster.

Paxton’s visual style is unassuming. You might expect the material to be full of high-contrast shadows to emphasize the theme of good versus evil, but that’s not so. The mise-en-scène feels natural. Paxton, capable of playing sniveling bullies and kindly father figures, inhabits the latter mode effortlessly. McConaughey, too, dials his performance back from his usual showmanship. This plain quality of Frailty and its performances is interrupted on a few occasions, however. When Dad touches his victims, the filmmaking takes a sharp break from the modest style. All at once, Bryan Tyler’s score strikes a jump-inducing chord as Paxton flexes every muscle in a seizure-like state, and cinematographer Bill Butler tilts the camera and vibrates the image out of focus. Since these shots are described to us by McConaughey’s narrator, we must assume that they come from his perspective. If they had come from his Dad’s, we might’ve seen the demons. And if the viewer thinks about the implications of that assumption, we might be able to guess his character’s identity before the film reveals it.

Paxton’s visual style is unassuming. You might expect the material to be full of high-contrast shadows to emphasize the theme of good versus evil, but that’s not so. The mise-en-scène feels natural. Paxton, capable of playing sniveling bullies and kindly father figures, inhabits the latter mode effortlessly. McConaughey, too, dials his performance back from his usual showmanship. This plain quality of Frailty and its performances is interrupted on a few occasions, however. When Dad touches his victims, the filmmaking takes a sharp break from the modest style. All at once, Bryan Tyler’s score strikes a jump-inducing chord as Paxton flexes every muscle in a seizure-like state, and cinematographer Bill Butler tilts the camera and vibrates the image out of focus. Since these shots are described to us by McConaughey’s narrator, we must assume that they come from his perspective. If they had come from his Dad’s, we might’ve seen the demons. And if the viewer thinks about the implications of that assumption, we might be able to guess his character’s identity before the film reveals it.

Frailty contains a few confusing shifts in perspective that raise questions. Perhaps they represent intentional equivocations in the material, or perhaps they’re evidence of a first-time filmmaker just learning how image and camera placement occupy specific perspectives. Most of the time, the camera is objective, observing a scene as it unfolds. But the story, told in flashback, is related from McConaughey’s character to Boothe’s FBI agent, so it should be from his perspective. So what should one make of the scene in which Dad sees an angel—a misguided moment not only because of its perspective confusion but poorly aged CGI? The scene is a flashback-in-a-flashback, shot from Dad’s perspective. Working under a car, he sees the undercarriage transform into a cathedral interior, and a winged angel descends toward him with a flaming sword. Although the story is told from McConaughey’s point of view, the perspective shifts confusingly here. Most other scenes occupy Fenton’s subjectivity, leading to the assumption on our part that McConaughey is the grown-up Fenton. But in the film’s climactic moment, when McConaughey reveals himself to be Adam—who has since carried on his father’s mission and plans to destroy Agent Doyle, a demon—the perspective of the entire movie becomes suspect. Did McConaughey’s adult Adam tell the story from Fenton’s perspective to give Doyle a false sense of safety?

While we attempt to parse out Paxton’s visual logic, he eliminates doubts about his characters in a scene back at FBI headquarters. Several agents watch security footage of McConaughey’s character sitting in the lobby, but somehow the footage is distorted and obscuring his face. The other agents who saw him also experience a strange lapse in memory and cannot describe the culprit. The implication is that God is protecting the killer, and thus, both Dad and later Adam were justified in their righteous murdering of seemingly innocent people, who, by that logic, were actually demons in disguise. These notes of clarification cannot be construed as Adam’s distorted perspective or the justifications of a madman. Paxton shoots them objectively, presenting them as real. Viewers who doubted Dad, which is most of us, are proved wrong. Alas, these moments rob Frailty of the ambiguity that otherwise proves challenging and open-ended, delivering instead a final declaration that answers our questions.

If the film leaves any lingering questions, it’s for those who believe in God (I myself do not). People of faith may watch Frailty and feel it implants some doubt as to whether those who kill in the name of God are telling the truth—a disturbing notion, to be sure. Most of them end up claiming insanity when they inevitably appear in court. But what if that’s just a legal strategy? What if these individuals don’t realize they’re insane, and they really believe that God gave them instructions to kill? And what if, for those who believe that sort of thing, it’s true? The Lord works in mysterious ways, I suppose. Or what if it’s not an angel that compels them, but a demon who appears in the form of an angel in a cruel trick? Any one of these possibilities is frightening to consider.

For the rest of us, Frailty provides a dark tale about a boy who realizes the world is more complex than he once thought—something every child learns eventually. Most children go through a process where they begin to see their parents through less worshipful eyes or finally realize there’s a world beyond their hometown. Fortunately, most of our youthful disenchantments don’t involve finding out Dad is an axe-murderer or the world is rife with demons. In any event, Paxton creates a memorable story that, while supplying too many answers about its own ambiguities, offers the chance to find multiple readings. It’s also a chilling idea and a frightfully good twist when McConaughey reveals himself. And as an actor who has faced off against Xenomorphs, Predators, and Terminators, Paxton’s confident first film as a director (he also made The Greatest Game Ever Played in 2005) makes one wish the late filmmaker had more opportunities behind the camera before his death in 2017.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted on Patreon. Thanks for your continued support, Brian R.! )

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review