Florence Foster Jenkins

By Brian Eggert |

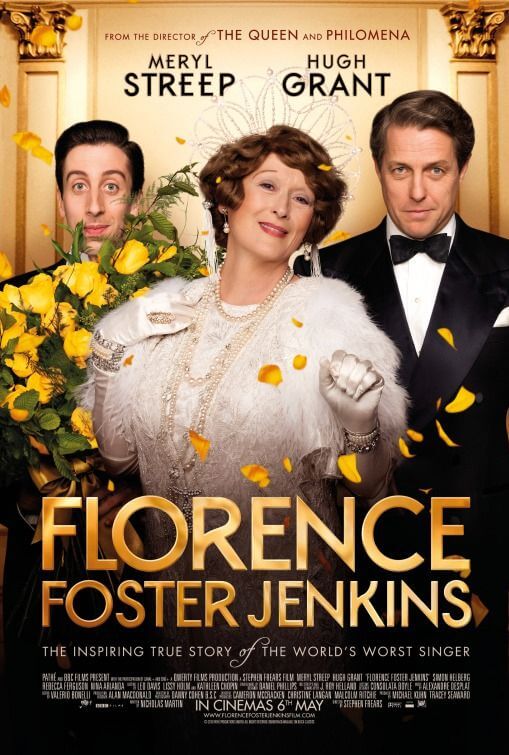

“Ours is a happy life,” says St. Clair Bayfield, husband to Florence Foster Jenkins, the titular subject of Stephen Frears’ latest film. Jenkins, here brought to comic and sympathetic life by Meryl Streep, was a member of Manhattan’s privileged elite in the 1940s, where her considerable wealth provided financial backing for the performing music scene. A famously awful songstress, Jenkins lived an ignorance-is-bliss life in which she held private concerts for grateful high-society members at her very own Verdi Club, for which a few critics wrote positive reviews in exchange for her husband’s bribe. Despite the title, Florence Foster Jenkins mostly follows St. Clair, played by an outstanding Hugh Grant, who uses all the power his wife’s money and influence afford him in order to preserve her blindly enthusiastic joy of performing onstage. Frears balances a light comedy tone with some equally light dramatics for an enjoyable trifle, although the two central performances remain the primary draw, and the treatment is occasionally problematical.

A crowd-pleaser in the most predictable sense, Florence Foster Jenkins avoids a potentially cynical (and more interesting) angle on the story, one with which the film’s resident antagonist, New York Post critic Earl Wilson (Christian McKay), could no doubt sympathize. After all, the sole reason Jenkins ever makes it on stage is because she buys her way there. Surely, more talented but less successful singers of the era resented Jenkins for having more opportunities solely because of her money. New York’s top composers and instructors indulged Jenkins’ tone-deaf performances because she remained a devoted patron to music, holding elaborate fundraisers where she served sandwiches galore and bathtubs full of potato salad. Audiences (eventually) indulged her terrible, albeit heartfelt performances with a stroke of irony, while she remained oblivious to their mocking derision for most of her life.

Screenwriter Nicholas Martin doesn’t tackle the material in any philosophical sense and writes the titular character on wholly sympathetic terms. Martin could have explored a discussion about artistic responsibility, as in knowing that you’re dreadful and getting off the stage. Or whether the audience and critics have a responsibility to willingly embrace an artist who appears to enjoy performing regardless of her deficient talent. But Frears and Martin spend the first half of their film exposing various characters to Jenkins’ horrific repertoire, and then watching the assorted reactions of riotous laughter or barely contained disbelief, much to the viewer’s delight. Meanwhile, the bluehairs who attend her parties and private theater performances barely understand what’s going on and can hardly hear her strangled cat recitals.

Enter Cosme McMoon (Simon Helberg), a private pianist hired to play alongside Jenkins during sessions with her vocal coach—Metropolitan Opera conductor Carlo Edwards (David Haig). Cosme is conflicted about whether he should continue to work for her, and yet she provides him with a fruitful salary. Gradually, Cosme learns that Jenkins just doesn’t know any better. Her husband has sheltered her from any outright criticism, having paid off critics and music lovers to behave as if they’re overcome by her glorious voice. At first, it seems as though St. Clair has aligned himself with Jenkins out of an unparalleled selfishness; especially after we learn he spends his days with Jenkins and his nights at his apartment, which his wife pays for, partying with his mistress (Rebecca Ferguson). But as we learn more about Jenkins and her husband, we realize there’s more to the story.

It’s all quite tragic, even if that point isn’t emphasized too heavily by the film. To be sure, Jenkins is versed enough in musical theory to know when she hears a good singer or piano player, but when she hears herself, she hears the voice of an angel. Perhaps that’s not her fault either. She was a child prodigy pianist and played a recital for President Hayes at the age of 8, but she contracted syphilis from her first husband, causing irreparable nerve damage throughout her body. She’s left incapable of playing the piano and has lived with syphilis longer than anyone in the pre-antibiotic age should have. Then again, the film never mentions there being anything wrong with her ears. Could she not hear what she sounded like? At any rate, she uses her family money to buy her way into a sellout show at Carnegie Hall. Some might consider that an artistic crime. No matter. Her enthusiasm is contagious and contains the same ironic admiration for something so plainly awful that Tim Burton demonstrated in 1994 with his masterpiece, Ed Wood.

As recently as last year’s Ricki and the Flash, Streep has demonstrated that she can carry a tune, and the indomitable actress very obviously has a blast recreating Jenkin’s off-key sounds, which recall something between chimp eeks and a strangulation of opera itself. You feel embarrassed for the character, until, that is, the film convinces us that letting the lady sing is perhaps the more noble option. Streep’s performance feels more like a force of nature next to the carefully modulated, three-dimensional portrayal by Grant, who shows an incredible range. At any moment in the film, Grant’s character is required to maintain his appearance as a supportive husband, while on the other hand, he’s aware that she stinks; and yet, if anyone in the audience laughs, he’s bound to escort them out of a packed theater, quiet them with a stern glare, or simply attack.

Frears and Martin tell the story through St. Clair’s eyes in order to bond the audience with their subject; without him, we would be left alone with an oblivious woman otherwise deserving of Wilson’s assessment in print. It’s a clever ploy on the part of the filmmakers, and a wholly artificial-if-effective one. Let’s hope Oscar voters think of Grant come awards season, as a Best Supporting Actor statue seems like a strong fit for this complex role. The rest of the production adopts an authentic but stagey feel, with gorgeous sets by Alan Macdonald and striking costumes by Consolata Boyle—all captured in clean lensing by Danny Cohen. Elsewhere, Alexandre Desplat’s score almost need not exist next to Streep’s handful of hilariously screeching enactments, which must be heard and seen to be believed.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review