Elle

By Brian Eggert |

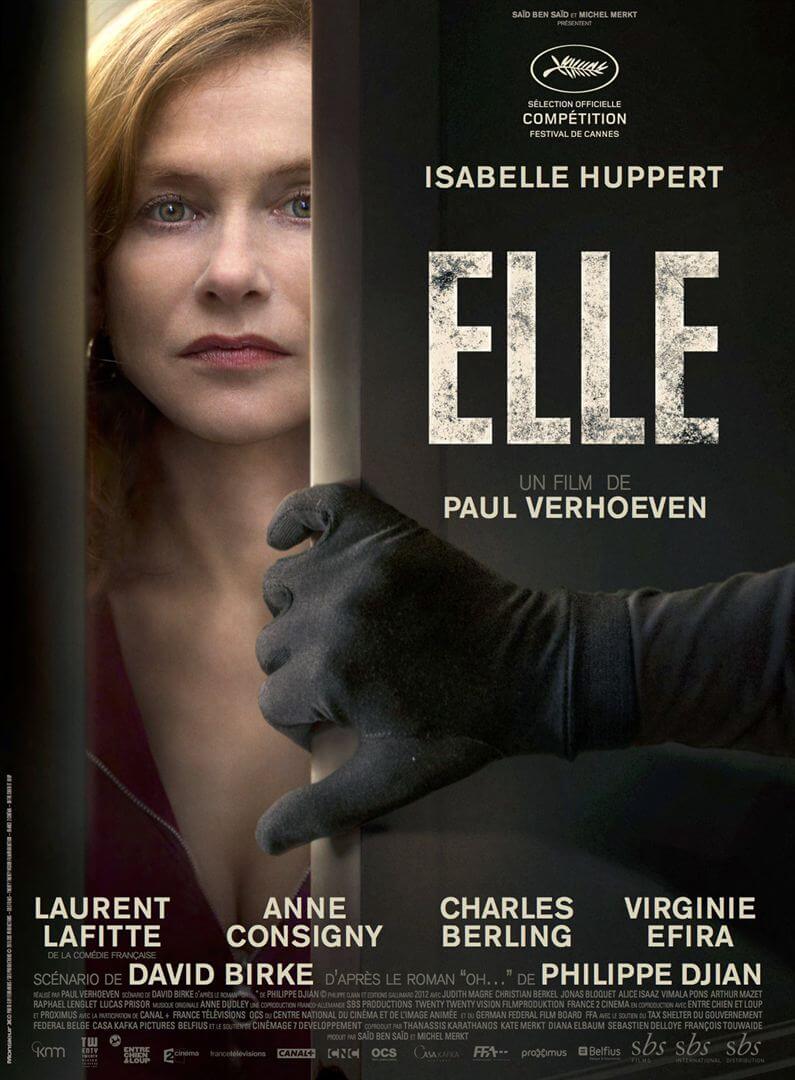

Played with inscrutable elegance and wry malice by Isabelle Huppert, Michèle Leblanc is a wealthy and successful co-owner of a Parisian videogame company. When we first meet her, the middle-aged Michèle might appear to be the heroine of a revenge thriller. In the first scene of Paul Verhoeven’s Elle, she is sexually assaulted by a masked intruder. The crime’s only witness is the victim’s smoke-colored feline, who looks on with indifference. After the incident, Michèle quietly cleans up the mess, takes a bath, and has dinner with her son as if nothing happened, never reporting the incident to the police. She casually tells her friends about it at a restaurant, following her account with “Let’s order.” And rather than pursue her rapist in a typical revenge scenario, what comes next proves far more shocking and less straightforward. Verhoeven’s film does not just defy a standardized formula of a psychological thriller; it keeps its audience guessing by centering on Michèle, who proves far more compelling than a banal rape-revenge yarn.

However, be warned, screening Elle could result in a heated debate about the film’s intent and meaning. Most American moviegoers won’t know what to make of their viewing experience, leading to dismissive remarks that the filmmaker and writers did not have control over the material (the word “mess” has been thrown around a lot). Some have censured the film as misogynistic, whereas others have celebrated its feminist overtones; some have called it exploitative, while others have proclaimed its treatment to be stylish and elevated. But such broad assessments deny Verhoeven’s masterful control of his craft, as well as the complexity of his perspective. Whether you look at his early Dutch films (Turkish Delight, Soldier of Orange, The Fourth Man) or his Hollywood breakthroughs (RoboCop, Total Recall, Starship Troopers), each has more to offer than face value, proving multi-textual, perverse, morally ambiguous, riotously funny, and always highly readable.

Take Black Book, his 2007 masterpiece about a Jewish entertainer in World War II who fights for the Resistance as a Mata Hari, only to fall in love with her mark: a German officer. Verhoeven does not make grand statements about sides or group perspectives; he puts himself in the viewpoint of the individual. Throughout his career, he has played with sexual and gender themes with a freedom other filmmakers would not dare. When he approaches Elle and how Michèle responds to her own rape, he does not make a sweeping statement about all women everywhere, nor is his film wholly a commentary about rape and its depiction in our culture. Instead, he delivers a rich and demented character study filled with obsidian-black humor and confronting material. While this kind of filmmaking may be atypical for Hollywood audiences, it’s more commonplace in the film’s French language.

After all, David Birke’s screenplay, based on the novel Oh… by Philippe Djian, was originally translated from French to English in hopes of an American production. But Verhoeven was unable to convince an American actress to play Michèle, having asked names like Nicole Kidman, Charlize Theron, and Julianne Moore. Ever-aware of how oversensitive American audiences can be (his Basic Instinct received protests for its depiction of a bisexual killer), the director resolved to re-translate the story back to French to shoot in Paris. Relocating, he learned Huppert had already voiced interest in the project. At 63, Huppert has emerged as one of today’s finest performers, having starred in several works by Claude Chabrol and Michael Haneke; though, her performance in Elle most recalls her role in I Heart Huckabees as an existentialist who believes the universe is chaotic and indifferent to human desire.

After all, David Birke’s screenplay, based on the novel Oh… by Philippe Djian, was originally translated from French to English in hopes of an American production. But Verhoeven was unable to convince an American actress to play Michèle, having asked names like Nicole Kidman, Charlize Theron, and Julianne Moore. Ever-aware of how oversensitive American audiences can be (his Basic Instinct received protests for its depiction of a bisexual killer), the director resolved to re-translate the story back to French to shoot in Paris. Relocating, he learned Huppert had already voiced interest in the project. At 63, Huppert has emerged as one of today’s finest performers, having starred in several works by Claude Chabrol and Michael Haneke; though, her performance in Elle most recalls her role in I Heart Huckabees as an existentialist who believes the universe is chaotic and indifferent to human desire.

Michèle takes a similar view when she says, “Shame isn’t a strong enough emotion to stop us doing anything at all.” She spends her days trying to convince her younger, male videogame designers to embrace savage advice from their female superior: “When the player guts an orc, he needs to feel the blood on his hands,” she explains. Meanwhile, she maintains an affair with Robert (Christian Berkel), the husband of her business partner and best friend Anna (Anne Consigny), because, she explains with utter dispassion, “I wanted to get laid.” Michèle does not tolerate infidelity herself, though; her ex-husband, Richard (Charles Berling), appears foolish in a romance with a young grad student. Perhaps this is why Michèle seems so offended when her garish mother (Judith Magre) takes up with a much younger man and announces plans to marry him. And then there’s Vincent (Jonas Bloquet), Michèle and Richard’s naïve and dopey son who works in fast-food and seems blind to the fact that he couldn’t possibly have fathered the newborn child of his harsh girlfriend (Alice Isaaz), based on the child’s skin tone.

Managing what often appear to be the petty needs of those around her, especially men, may seem like the actions of a protagonist who is subjected. Certainly, her reaction to her own rape deems the event to be almost a non-issue, aside from the constant pestering from her attacker. Sordid emails and subsequent intrusions into her home lead to a thorny series of exchanges, a cat-and-mouse relationship in which the mouse believes he’s in control. When Michèle engages in a sadomasochistic relationship with her attacker, she seems to enjoy the attention, and even the abuse (her remarks about her affair with Richard come to mind). But clues throughout the picture suggest that Michèle only appears passive; in fact, she’s several steps ahead of everyone else, including the audience. Note how the rapist’s fate somehow resolves the other conflicts involving her son, her affair, and her ex-husband. This is either hilariously fortuitous or the scheming machinations of a psychopath.

Best of all, Verhoeven’s film unfolds on Michèle’s terms and avoids explaining her every action or justifying her sometimes cruel and manipulative choices. Michèle’s motivations are her own; though, Elle is not without some hint to her behavior, even if there’s never a moment similar to Charles Foster Kane’s “Rosebud” revelation. Consider how, littered throughout the proceedings, there are vague references to an incident from Michèle’s distant past involving her imprisoned father, a child-killing monster who went on a spree when she was just a girl. Given her parentage, passers-by dump their food in her lap and look at her in disgust; others maintain suspicions as to whether Michèle was involved somehow. And while such insinuations never develop into more than allusion, we cannot help but suspect her, even as we strangely admire her ability to keep it all secret. Huppert, delivering (if you’ll forgive the hyperbole) the best performance of 2016, plays every note with measures of elusive coldness and bemused humor, her composure never failing to draw out unexpected and often shocking developments for the character—some of them quite hilarious, others horrifying.

Best of all, Verhoeven’s film unfolds on Michèle’s terms and avoids explaining her every action or justifying her sometimes cruel and manipulative choices. Michèle’s motivations are her own; though, Elle is not without some hint to her behavior, even if there’s never a moment similar to Charles Foster Kane’s “Rosebud” revelation. Consider how, littered throughout the proceedings, there are vague references to an incident from Michèle’s distant past involving her imprisoned father, a child-killing monster who went on a spree when she was just a girl. Given her parentage, passers-by dump their food in her lap and look at her in disgust; others maintain suspicions as to whether Michèle was involved somehow. And while such insinuations never develop into more than allusion, we cannot help but suspect her, even as we strangely admire her ability to keep it all secret. Huppert, delivering (if you’ll forgive the hyperbole) the best performance of 2016, plays every note with measures of elusive coldness and bemused humor, her composure never failing to draw out unexpected and often shocking developments for the character—some of them quite hilarious, others horrifying.

Though Huppert’s complex performance is an essential component of savoring Elle, Verhoeven’s direction of uncomfortable dinner parties and excruciatingly tense scenes of sexual violence wonderfully balance his refined touches with his more provocative sensibilities. His cinematographer Stéphane Fontaine, who also photographed this year’s Captain Fantastic and Jackie, shoots in subtle beauty with fluid camerawork, while scorer Anne Dudley creates music worthy of Hitchcock or De Palma. And though the director remains best associated with boldly satirical films like RoboCop that ridicule its culture, Elle is something else altogether, operating through sophisticated and gracefully restrained moments of humor and mystery. Fortunately, the director has aligned himself with an extraordinary performer versed in extreme emotions felt under a deceptively cool exterior. From voyeurism to psychopathy, from sexual freedom to the absurdity of social pressures, Verhoeven revels in exploring what Michèle is capable of and indulges her twisted side, and his own.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review