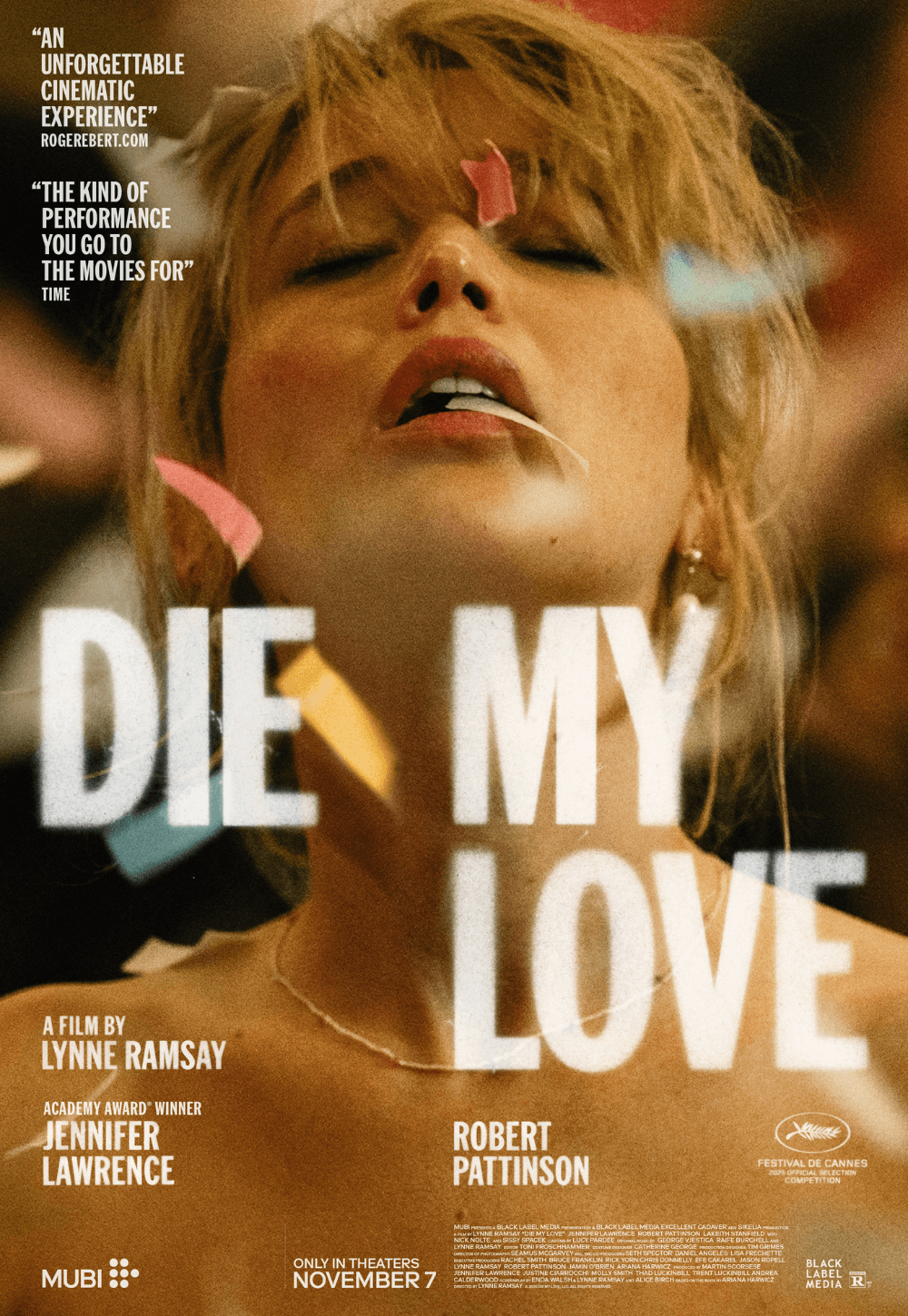

Die My Love

By Brian Eggert |

Some movies wrap you in a warm blanket, helping you escape into a cinematic dream—a world that welcomes you and leaves you with a sense of order in the universe. Others slap you in the face, leaving you with a nosebleed and tears welling up in your eyes. And that’s just in the first few minutes. Next, they punch you in the gut, rub your face in the mud, and leave you there, unable to get up until you catch your breath. Once you do, you’re left with the realization that the world is chaos, so what’s the difference if the whole thing burns? Die My Love is such a film. Lynne Ramsay adapts Argentinian writer Ariana Harwicz’s 2012 novel, a savage depiction of postnatal and bipolar depression told from the perspective of a woman who unravels after having a child. Ramsay and co-writers Alice Birch and Enda Walsh capture the volatile and unpredictable psychology in their portrait of the protagonist, performed by Jennifer Lawrence in a stunning turn that recalls her most unbridled moments from American Hustle (2014). Bleak and unflinching, it’s a feel-bad movie of the highest order.

Ramsay has already made an essential film about motherhood with We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011), starring Tilda Swinton as the icy, loveless parent to Ezra Miller’s disturbed and psychopathic child. Compared to Die My Love, that film feels relatively tame and accessible. Although I have not read Harwicz’s book, first translated into English in 2017, I can only assume that Ramsay’s adaptation loses some of the psychological depth and reasoning that come with translating first-person literature to the screen. Thankfully, Ramsay avoids compensating for her protagonist’s inner voice with narration or some other clunky device. Instead, she disregards commercial imperatives for a defiant, singular experience, where the viewer watches a woman disintegrate as though passing by a car accident, mouth agape at the horror splayed on the highway.

Lawrence plays Grace, whose man, Jackson (Robert Pattinson), moves them to the isolated Montana home that belonged to his late uncle, who recently killed himself in the house in such a nasty way that it leads to a morbid guessing game between Grace and her sympathetic mother-in-law, Pam (Sissy Spacek). When they first arrive, it’s all punk-rock dancing and animalistic sex. Before long, Grace and Jackson have a baby. But rather than working on a novel in her downtime as she intended, Grace finds herself in a restless, perpetually disillusioned state: “Stuck between wanting to do something and not wanting to do anything,” she says. Left alone for days on end by Jackson, who travels for work, she contends with the house, her baby, and her unreliable mind that often descends into waking fantasies, fits where she repeats the word “alrighty,” and a general disinterest in domestic life.

Structured in a loose chronology that often veers into the nonlinear, Die My Love leaps through time, sharing volatile incidents and twisted daydreams in Grace’s mind. One recurring presence belongs to Lakeith Stanfield, who plays a character she once saw at a grocery store. That image fuses with another of a man on a motorcycle, who occasionally rides by the house, stealing a prolonged look at Grace, to become her fantasy of an illicit lover. She needs those erotic dreams because, when Jackson returns, his libido is unresponsive, and the condoms in his glove box indicate why. Jackson tries to soothe Grace’s loneliness by bringing home a new dog, but the animal’s constant barking only loosens the screws in her brain. And so, Grace takes to walking to the local gas station for mac-and-cheese only to berate the clerk for making small talk, or she visits Pam, who sleepwalks down a dirt road at night, rifle in hand. Not surprisingly, Grace relates best to Harry (Nick Nolte), Jackson’s father, who is separated from Pam and suffering from dementia.

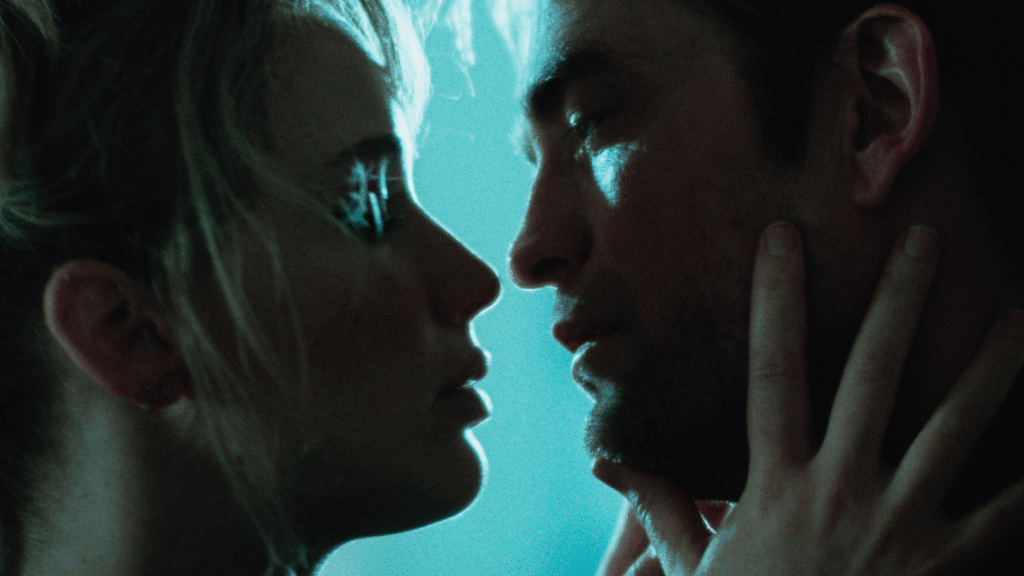

Captured in saturated colors and the boxy Academy aspect ratio by Seamus McGarvey’s cinematography, the film has the quality of a bad dream or hallucination, accented by digital filters that turn night scenes into a milky, eerie gray-blue. Everything about it, from Paul Davies’ sound design to the fragmented, impressionistic editing by Toni Froschhammer, underlines Ramsay’s ferocious vision. Anyone familiar with Ramsay’s filmography should know not to expect accessible, mainstream fare. Her films have an unflinching psychological rawness, compounded by lyrical aesthetics that inhabit her characters’ interior worlds. A few notes of humor even appear on the soundtrack, from “Mickey” on repeat to David Bowie’s apt “Kooks.” But otherwise, the material brims with potent symbolism, such as the wild black horse that roams the forest near Grace’s home. Doubtless, she yearns for the animal’s freedom, evidenced by her long sojourns into the woods alone, often in the middle of the night. But like the horse, she winds up in a collision with her reality.

Alternately horrifying and funny in a twisted kind of way, the film sometimes amuses when Grace proves immune to chit-chat at a party with friends and resolves to jump into the pool in her underwear. But more often, it’s an abstract assault of unpleasantness, strained interactions, and harsh outbursts—both provoked and not. One scene finds her tearing up the bathroom, ripping out the sink, and scratching the wallpaper until her fingers bleed. Later, she almost leaps out of a moving vehicle and then succeeds in throwing herself through a glass door. Her self-destructive tendencies prompt Jackson to marry her, perhaps because he thinks that will make her happy, or maybe only so he gains the legal authority to have her committed. However, Grace seems most in her element on all fours like a cat, prowling around the house or the overgrown field on their property—an image evoking the subject of Andrew Wyeth’s 1948 painting Christina’s World.

Lawrence has played this sort of role before, most abundantly as a heavy-handed (and punctuated) metaphor for Mother Earth in Darren Aronofsky’s mother! (2017). Her performance in Die My Love clearly draws from the comparatively grounded Gena Rowlands in A Woman Under the Influence (1974). Like that performance, the viewer watches Grace from the outside, unable to penetrate the character’s troubled mind. Lawrence is spectacular in the role, though the film’s general unpleasantness will likely dissuade an Oscar nomination. Pattinson, too, delivers an amplified performance as a fraught character, too impatient, immature, and simple-minded to intuit what could help Grace. After putting her in a hospital, he welcomes her back to a newly remodeled home, as though that would fix her. Spacek is also excellent, as Pam approaches Grace with understanding, concern, and perhaps more than a little identification.

Die My Love arrives just a few weeks after Mary Bronstein’s darkly comic portrait of motherhood in If I Had Legs I’d Kick You—a similarly surreal plunge into the headspace of a mother, anchored by a marvelous lead performance. But comparing Ramsay’s film to Bronstein’s is like comparing spontaneous combustion to a stubbed toe. This is a deeply unpleasant viewing, filled with incendiary characters whose motivations and behaviors range from baffling to abhorrent. The film is a fiery catastrophe in a way I admire, in a way few other films would ever dare approach. It takes bravery to make something that refuses to pander to the audience’s needs. Ramsay doesn’t greet her audience with the desperate need to be liked that most commercial cinema does; she asks that we meet Grace on her terms. And while I can’t imagine wanting to revisit this punishing, thoughtfully made film anytime soon, it’s another distinct entry in an uncompromising artist’s filmography that I won’t soon forget.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review