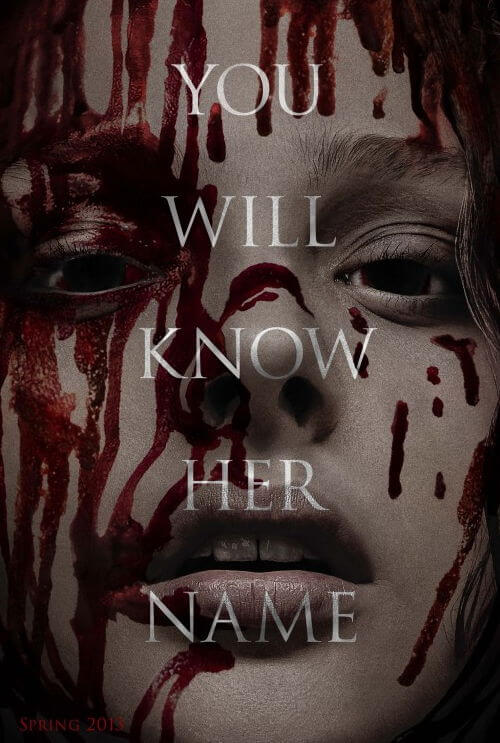

Carrie

By Brian Eggert |

Targeting a new generation of viewers unfamiliar with Stephen King’s story, director Kimberly Peirce’s version of Carrie offers few surprises or innovations on the 1974 source novel. Brian De Palma adapted a perfectly cinematic interpretation in 1976, starring Sissy Spacek as the titular introverted teen and Piper Laurie as Carrie’s Bible-thumping mother (both performances were nominated for Oscars). However, there was no talk of awards for the later attempts to cash in on the book and initial film’s success: the 1988 Broadway musical that flopped; the haphazard sequel called The Rage: Carrie 2, released in 1999 and justifiably dismissed ever since; and the TV movie Carrie from 2002, also best left forgotten. No awards should be given to Peirce’s film either, which is less a new take on King’s book and more a remake of De Palma’s classic. The new Carrie offers no fresh insights into the material and delivers far less than what De Palma achieved both thematically and cinematically.

Following a telekinetic teen who exacts revenge on her malicious classmates after a bloodily traumatic prom night, Peirce’s film exists for almost no reason except to provide a modernish billboard on which ScreenGems can sell their name-brand title to younger audiences. That statement is qualified by “almost” because one could make the case that Carrie is relevant for the victims of a recent cyber-bullying outbreak, or even those who’ve read headlines about the extreme reactions thereto (including suicides and retaliations). As a result, those completely unfamiliar with what came before might draw something worthwhile out of this version. For the rest of us, comparisons between the 1976 and 2013 versions are unavoidable; the filmmakers have left us no choice since the screenplay, credited to Lawrence D. Cohen (who wrote De Palma’s Carrie) and Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa, follows the same basic structure of De Palma’s adaptation. De Palma’s version is never put out of our minds, and so throughout we’re forced to consider Peirce’s flat scenes against the cinematic finesse of De Palma’s direction.

Though she made the devastating indie drama Boys Don’t Cry, Peirce never manages to weave the worn-out narrative threads into a convincing drama or a shocking thriller on its own. With the arrival of her first period in the girls’ locker room, Carrie White (Chloë Grace Moretz) is publically humiliated by her bitchy, orange-tanned classmate Chris Hargensen (Portia Doubleday), who filmed the ordeal on her smartphone. Once it’s posted online, Carrie’s humiliation leads to her first outburst of telekinesis. At home, the relationship between Carrie and her mother, Margaret (Julianne Moore), alternates between abuse and a power struggle, with Carrie developing into a confident woman and the deranged Margaret losing grasp on the one thing over which she holds control. Meanwhile, Chris and her bad-boy beau Billy Nolan (Alex Russell) plot their revenge on Carrie after their prom tickets are revoked as punishment by the sympathetic gym teacher, Ms. Desjardin (Judy Greer). And regretful classmate Sue Snell (Gabriella Wilde) plans to atone by convincing her dim-but-good-hearted jock boyfriend Tommy Ross (Ansel Elgort) to take Carrie to prom.

Peirce develops a mild level of tension leading up to prom night, but once the bucket of pig’s blood comes showering down on Carrie’s head in a rain of CGI red (De Palma doused Spacek in a coat of corn syrup and food coloring, but there’s nothing so sticky about the animation Peirce uses to save time on cleanup between takes), the film loses all technical credibility and celebrates the protagonist’s retribution to sadistic extremes. In that moment, Moretz’s performance goes from a sensitive loner to a cold-blooded killer; her Carrie hissing and moving like a possessed dinosaur, her head cocked to the side, her arms raised and bent. She even elevates herself like some kind of demon. She’s hardly the reactionary, emotionally shattered version of Carrie as represented by Spacek. Moretz’s performance turns Carrie into a monster. She uses her mental powers to lift up her victims and seems to relish the influence she has over them, a creepy smile appearing on her face as she ends their lives. Peirce dwells on the prom killings for far too long, savoring Chris’ death in particular, until the point where Carrie can no longer be seen as a victim, despite crying out in apologies in the aftermath at home.

Moretz’s casting and performance are offensively misguided. Spacek’s scrawny frame and skeletal appearance gave her Carrie the undeniable look of an outcast next to her more classically attractive costars, Nancy Allen and Amy Irving. Moretz, on the other hand, looks like one of the cool crowd who pretends to be withdrawn. Having played strong-minded, wise-beyond-their-years youngsters in fare like Kick-Ass and Let Me In, it’s difficult to see Moretz as anything but a smart, capable teen, rather than the downcast character she’s supposed to be playing. When she tries to behave reserved and fragile in the face of social rejection, it just doesn’t work to sometimes laughable degrees. Moreover, the filmmakers just couldn’t resist casting an actress who, disgustingly, became a fanboy sex symbol under a purple wig at the age of 10. Now 16, she’s no more de-sexualized in this outsider role behind her faux strawberry blonde hair and pouty lips. Imagine another version of Carrie where the filmmakers adhere to how King originally wrote his titular character: a rotund girl stricken with acne. Now that would be a film with a new take.

The film’s one standout performance besides Greer’s Ms. Desjardin is Moore’s interpretation of Margaret, which is restrained next to Piper Laurie’s roaring, fanatical zealot. Moore quietly broods behind glaring eyes and incensed whispers instead of preaching loud sermons, her more impassioned reactions internalized by her not-so-subtle tendency to self-mutilate or slam her head against the wall. Moore’s presence emphasizes the film’s sole redeemable point—the tragedy that all Carrie has in the world is her mother, and her mother sees her as a “cancer” on her faith. But Peirce squanders our sympathies for Carrie when she advances the character’s level of control over her telekinesis and allows her to consciously torture fellow students during the prom sequence, whereas Spacek’s version seemed to react on primal instincts after her complete emotional breakdown. It’s a fine but crucial line. Given the off-putting depiction of Carrie, Moretz’s unsuitable presence, and Pierce’s underwhelming presentation in the shadow of De Palma’s direction, the new Carrie is nothing short of pointless.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review