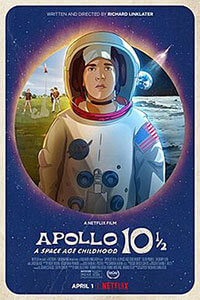

Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood

3 Stars- Director

- Richard Linklater

- Cast

- Milo Coy, Jack Black, Glen Powell, Zachary Levi, Josh Wiggins, Lee Eddy, Bill Wise

- Rated

- PG-13

- Runtime

- 98 min.

- Release Date

- 04/01/2022

Richard Linklater grew up in a suburb of Houston comprised of mostly NASA families. Born in 1960, the writer-director, like many Americans, spent much of his young life anticipating the first lunar landing in 1969. He injects those dreams and childhood experiences into an animated work of fabulist autofiction, Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood, which debuted on Netflix. Part boyish reverie, part remembrance of “life back then,” the rotoscoped movie plays like a story told by grandpa to the grandchildren—only grandpa tends to blend fiction into his personal history. Narrated by Jack Black, Linklater’s alter-ego Stan recalls his experiences as a fourth-grader whose cinematic memoir includes some mild exaggeration: He claims NASA built their lander too small. So two officials (Zachary Levi, Glen Powell) enlisted the 10-year-old Stan (Milo Coy) to fly a secret mission to the Moon, thus winning the space race. Before Neil Armstrong made one giant leap for mankind, Stan completed a secret solo mission. That’s the conceit, anyway.

Set aside that fictionalized flourish, which occupies only a small section of this 98-minute feature, and the rest is a fascinating embrace of nostalgia. For Stan, the future seemed hopeful and full of possibility, but he was preoccupied with the everyday like most children. In long passages, he recounts trips to the bowling alley; his father’s job at NASA in shipping and receiving; his mother’s innovative ways of preparing food for six children; his family’s television rituals; Roman candle wars; trips to Astroworld; Saturday night movies; and riding bikes in DDT clouds. Stan’s reminiscence of free-range childhood also recognizes how life has become safer—no more piling the family into the back of a pick-up truck for an afternoon at the oil-polluted beach. The fighting in Vietnam, numerous assassinations, and protests throughout the country in the 1960s felt like another world. Nearly the entire movie flows from one section of Stan’s life to another, amounting to a narrated portrait of a time and place. Life seemed simpler, and technology was “new and man-made and therefore better.” Parents were different. Children were different. Everything was different.

After a while, you realize that Apollo 10 ½ will remain in reflection mode. The story about NASA recruiting Stan for their mission becomes an afterthought—a flimsy hangar on which Linklater drapes his memories, and a reverie of an imaginative boy who couldn’t stay awake during the actual Apollo 11 landing. “You know how memory works,” says Stan’s mother to his father. “Even if he was asleep, he’ll somehow think he saw it all.” Still, Stan is a likable storyteller, and Linklater’s preoccupation with his past and the passage of time always leads to thoughtful observations. The movie has the current of Boyhood (2014) combined with the personal quality of Linklater’s other coming-of-age comedies. Stan might be just a few years away from becoming Mitch Kramer in Dazed and Confused (1993) and a decade away from Jake Bradford in Everybody Wants Some!! (2016). And like those films, Apollo 10 ½ has wall-to-wall music from the era, courtesy of music supervisor Randall Poster.

To achieve the film’s distinct rotoscoped look, Linklater worked with Tommy Pallotta, his head of animation on Waking Life (2001) and A Scanner Darkly (2006). The technique involves animating over live-action footage, photographs, and television broadcasts, and using the animation to accentuate details. Pallotta’s team delivered a more cohesive and computerized approach to 2D computer rotoscoping than what we see in Linklater’s previous animated features, which used their trippy ideas to build visuals that could often diverge into the surreal. Rather, Apollo 10 ½ remains quite grounded, even realistic looking. But the viewer will notice subtle distinctions between animation styles in the movie. For example, everyday life looks crisp and sharp, whereas TV shows such as Bewitched and The Monkees or drive-in movies have a fuzzier appearance, like watercolors. Even so, the visual technique remains distinct, if not as eye-popping as Linklater’s earlier two animated films.

It would be all too easy to dismiss Apollo 10½ as a hunk of baby-boomer nostalgia told from the perspective of a white Texan man. And boy, is there a lot of telling, arguably more telling than showing, which marginally takes away from the animation. But Linklater understands his subjectivity and includes references to other perspectives, such as a news segment where a Black man wonders why billions were spent to put someone on the Moon when that money could have helped people in Harlem. These flourishes receive an understated “right on” from Stan’s hip older sister that resonates. Above all, he captures the spirit of an era when many people felt space would be the great unifying cause, epitomized by the first photo of Earth from space and the Apollo 11 mission. Although that proved painfully untrue, Linklater doesn’t give in to cynicism about the world today; it’s not a condemnation of the present but simply a personal and modest portrait of the past that underscores the value of dreaming and memory. Even if the film doesn’t attain the profound heights of Linklater’s other work, it’s easy to lose yourself in its groove.

Moon

Moon  A Scanner Darkly

A Scanner Darkly  Hit Man

Hit Man