28 Years Later

By Brian Eggert |

In 28 Years Later, a melancholy poem to new beginnings, director Danny Boyle and writer Alex Garland revisit the rage-infected world they created in 2002. With 28 Days Later, the filmmakers restarted the zombie genre for the twenty-first century, leading to one sequel (28 Weeks Later, 2007), countless imitators, and a resurgence of flesh-eating ghouls in horror cinema and pop culture that has continued well beyond the point of overexposure. Returning to what they started, Boyle and Garland have much on their minds—none of which could be called conventional. The new feature isn’t merely another kinetic exploration of epidemic survivors running about the UK from fast-moving infected. The world has changed since then, and the filmmakers’ approach has evolved along with it. Their film comments on the last quarter century of radicalization through Christian rapture theology, nationalism, traditionalism, and the manosphere, delivering an allusive critique of the lot. 28 Years Later is anything but straightforward post-apocalypse or zombie-adjacent fare, and it will undoubtedly confound audiences expecting Hollywood’s predictable legacy-sequel (or requel) treatment. That’s part of what makes it special.

A sharp contrast to Boyle’s last movie—Yesterday (2019), a light, high-concept yarn more appropriately attributed to its writer, Richard Curtis—28 Years Later finds the director once again crafting an inspired sequel to a film that solidified his reputation as a celebrated British auteur. Just as he revisited the characters from Trainspotting (1996) with the dispirited yet no less vital and energetic T2 Trainspotting (2017), his long-discussed second sequel to 28 Days Later thrives on deeper themes. Some of these Boyle echoes with visuals evocatively embedded into the proceedings by editor Jon Harris for an almost subliminal effect—such as archival footage of British soldiers marching and imagery of archers from Laurence Olivier’s Henry V (1944) shooting arrows. On the soundtrack, Boyle deploys a hypnotic chant of Rudyard Kipling’s poem “Boots,” recorded in 1915 by actor Taylor Holmes. This pointedly relentless and repetitive text underscores the psychological numbing and scarring of soldiers adherent to their cause.

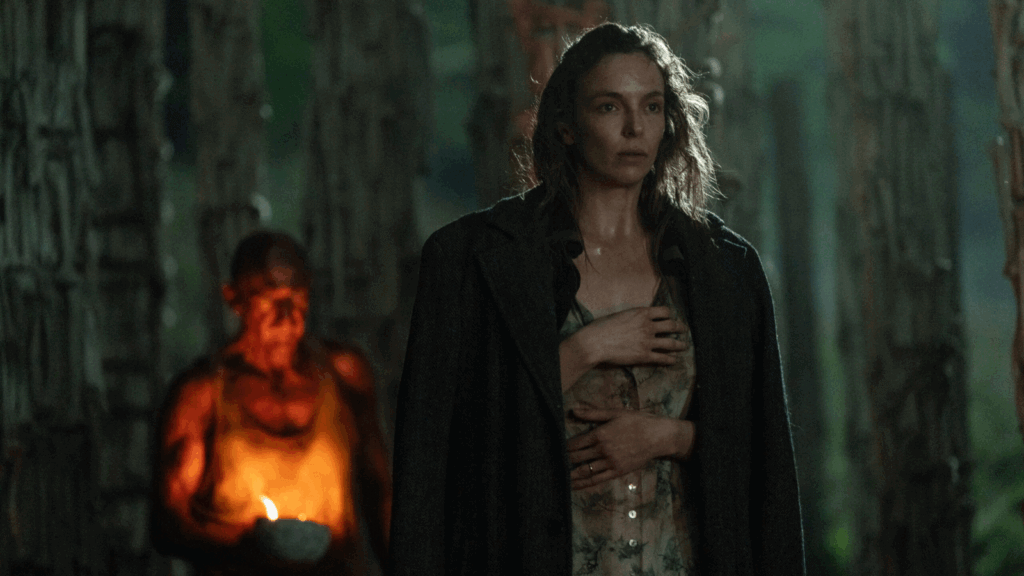

Through these intertexts, Boyle and Garland question the blind obedience and order expected by social and political groups, and how they weigh on the individual. Their dark fairy tale follows a 12-year-old boy, Spike (played in a subtle yet affecting performance by Alfie Williams), who breaks away from his father and, by extension, his rule-bound community. Living on a small island within the Quarantine Zone—the entire UK, whereas the rest of the planet has returned to normalcy—Spike has reached the age where his village expects him to prove his readiness for manhood on the mainland of Northern England, still teeming with the Rage Virus. Though Spike is young, his father, Jamie (Aaron Taylor-Johnson, his Kraven the Hunter swagger intact), believes he’s ready. Spike isn’t confident about his bow-and-arrow skills, and he would rather remain home with his mother, Isla (Jodie Comer), who’s stricken with a mysterious illness, including fevers and periodic senility. They have no real doctors on their island, so her ailment remains a mystery. Even so, led by his father, Spike must cross the narrow causeway that separates their tidal island from the mainland to test his training.

While Spike makes his first kill, the film considers how the infected have evolved in the last quarter-century. They’ve been around long enough that most of their clothes have rotted and fallen away, leaving throngs of naked infected to roam the landscape. Chubby iterations squirm on the forest ground, slurping worms and whatever else crosses their path. Garland also takes a cue from George A. Romero, who fathered the cinematic zombie with Night of the Living Dead (1968) and whose reanimated corpses became smarter with each successive film. By the time Romero made his fourth installment, Land of the Dead (2005)—greenlit in the zombie’s post-28 Days Later return to the zeitgeist, ironically enough—he introduced a thinking zombie called Big Daddy. Garland’s equivalent is an “Alpha,” a type smarter than the usual infected, boasting a swinging-dick hypermasculinity. Alphas have a penchant for tearing off heads with the spinal column attached and charging victims with the horrifyingly unstoppable momentum of a juggernaut. They lead a pack of infected people who survive on the local deer population and even procreate. Boyle and Garland suggest that those infected with rage no longer starve and die out, as they did in the original; they form a community around their shared rage, just as they do today in digital and sociopolitical bubbles.

After narrowly surviving his overnight sojourn to Northern England, Spike becomes disillusioned by his father’s mounting deceptions—one of them being that the only known doctor, Dr. Kelson (Ralph Fiennes), a general practitioner before the UK collapsed, is now insane and collects human corpses on the mainland for who-knows-what purpose. Desperate to help his mother, Spike sneaks back with Isla, who’s in varying states of delirium, hoping to find Kelson and cure his mother. Along the way, an interlude with an amusingly embittered Swedish soldier (Edvin Ryding), whose quarantine patrol boat was unfortunate enough to sink nearby, gives Spike his first exposure to another way of living—prompting his introduction to a smartphone, followed by an amusing critique of today’s cosmetically altered beauty standards. When they finally encounter Dr. Kelson, he looks chilling, given his regular body-wide applications of iodine to ward off the virus. He also introduces Spike to new ideas, such as paying tribute to the dead with an elaborate memento mori, a forest and tower assembled from bones.

Ever the electric visualist, Boyle and his returning cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle imbue 28 Years Later with a different kind of energy. Certain angles and scenes crackle with the same force as the 2002 film, with Mantle’s iPhone cameras replacing the consumer-grade mini-DVs from the original. The imagery’s soft edges and desaturated colors suggest Boyle and Mantle scrubbed a layer of skin off the footage until it looked similar 28 Days Later. Along with some impressionistic edits and unnervingly red night-vision shots of infected hunting and eating deer, the film engages in visceral and jarring formal choices that register as improvised rather than orderly. Boyle augments scenes with CGI, such as one that portrays an iffy-looking herd of deer. But elsewhere, a digitally assembled scene featuring an Alpha running beneath a starry sky adds to the storybook quality of the narrative. Regardless of these choices, 28 Years Later is a far more contemplative and searching film than its two predecessors; it’s even quieter, with a less pronounced soundtrack, foregrounding Spike’s search for an identity.

To whatever degree the credits roll on a disappointingly open-ended note—with a nod toward a sequel, the second of a planned trilogy penned by Garland, reportedly due in January 2026 and subtitled The Bone Temple—the movie concludes fittingly enough with Spike finding someone else like him. This is Jimmy, played by Jack O’Connell, who, following this year’s Sinners, plays another cult leader of sorts. Following a shocking introduction in the prologue, Jimmy, like Spike, has a tarnished view of his father—a holy man who welcomes the Rage Virus as a premillennialist sign of Judgment Day. Jimmy’s return in the last sequence is a bizarre, unsatisfying way to end the picture, though his bonkers crew prompts an amusing What the fuck? reaction to their tracksuits and out-there gymnasti-kills. After waiting so long for this sequel, I would have preferred a conclusive rather than episodic finale, but it promises another helping of the unexpected to come.

A stark commentary on the frightening subcultures operating in our society, which have only worsened since the COVID-19 pandemic, 28 Years Later reflects a world where rage has become commonplace—even something to build a community around. For all their ambitious ideas and irregular story choices, Boyle and Garland amplify the humanity on display with tender character descriptions captured in thoughtful performances, particularly from Williams, Comer, and Fiennes. With years of anticipation behind me, I now struggle to articulate what I wanted and expected from this sequel and how the film deviates. And though I cannot claim 28 Years Later fulfilled my abstract hopes, it’s nonetheless an intriguing, moving horror film that, not unlike the aforementioned Sinners, has a reach that goes beyond its subgenre. However, unlike Sinners, it’s not an instant triumph. Instead, Boyle and Garland made an expressive film that gave me pause and forced me to contemplate for hours before deciding how I felt about it. Whereas most films strive to align with moviegoer expectations, 28 Years Later shatters them in a refreshingly unpredictable way.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review