MSPIFF 2024 – Dispatch 3

By Brian Eggert | April 23, 2024

These films were screened at the 43rd Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival (MSPIFF43), which runs from April 11-25. Check here for the full lineup and check back for additional dispatches. Select films reviewed below will receive separate full-length writeups, some for their wider release, some exclusive to Deep Focus Review’s Patreon. In the meantime, here are some first impressions.

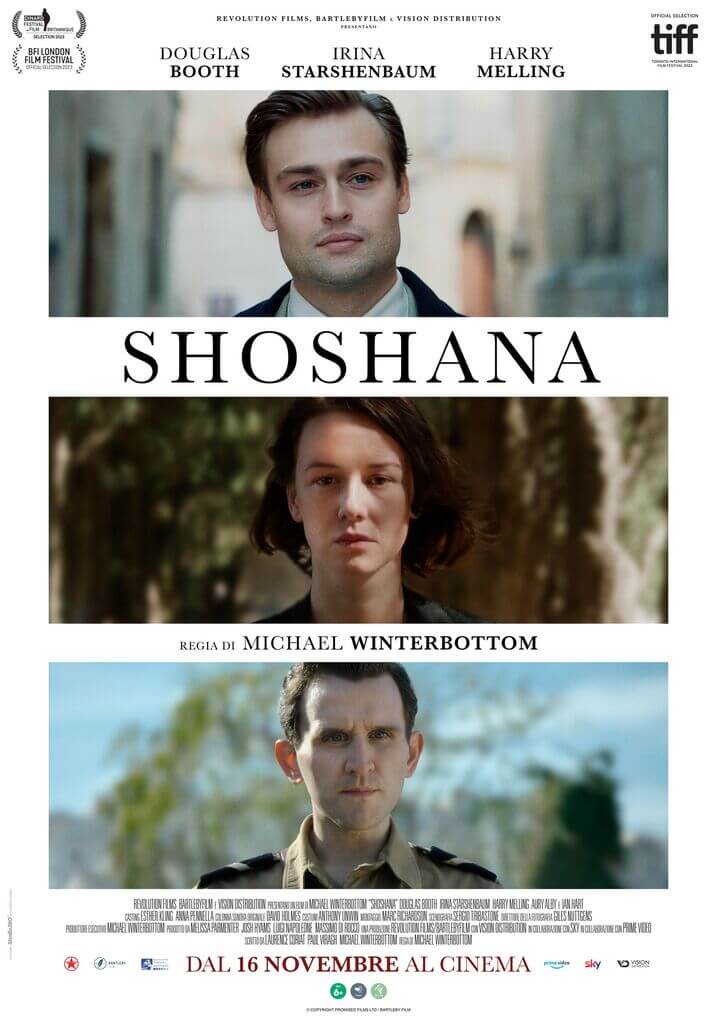

Shoshana

Shoshana

With Israel and Palestine locked in an entrenched conflict, Shoshana, the latest from British director Michael Winterbottom, is bound to evoke strong feelings. Yet, the film lacks any sense of passion despite its potential to prompt debate about a hot-button issue. Winterbottom and co-writers Laurence Coriat and Paul Viragh tackle a heightened chapter of history involving the titular character, the daughter of socialist Zionism co-founder Ber Borochov. Set during the period of British imperialism over what was Mandatory Palestine in the 1930s, the narrative confronts how Zionists in both the Irgun and Lehi paramilitary groups, which eventually merged into one entity, learned a few things from their British oppressors.

While the director often features documentary-level attention to history in his films, evidenced here by archival footage from the era, Shoshana presents a tale of star-crossed lovers whose political backdrop makes their relationship fraught, recalling similar stories from Casablanca (1941) to Allied (2016). Framing the narrative with occasional voiceover, Shoshana (Irina Starshenbaum) carries on an affair with British police officer Tom Wilkin (Douglas Booth), and both feel pressure from their respective sides to rethink their association. The tension becomes palpable when Wilkin’s new superior, Morton (Harry Melling, excellent), begins treating the comparably peaceful Irgun, of which Shoshana is a member, with the same zero-tolerance aggression as members of the Lehi.

The story meanders about, never quite settling whether it’s about a doomed romance, the Israel-Palestine conflict, or the central investigation that finds Morton determined to capture Lehi head Avraham Stern (Aury Alby). Of course, it’s about all these ideas at once, crammed into a two-hour feature that addresses none with enough dimension. And pompletely absent is any Palestinian perspective, which seems like a miscalculation on the filmmakers’ part. Then again, if the point is to show how the British imperialists perpetuated conflict in the region, giving Zionists an example to learn from, then mission accomplished. But it still feels strange that there’s not one substantial Palestinian character in the film.

Winterbottom has been developing this story, which has been covered in several books, for well over a decade, and the director had actors such as Colin Firth and Matthew McFayden attached to star. It aches to imagine how much more charisma one of them would have brought to the Wilkin role. Booth isn’t up to the task and lacks chemistry with Starshenbaum, who, for her role, brings a fascinating, unknowable quality that reminded me of Marlene Dietrich in A Foreign Affair (1948) or Cate Blanchett in The Good German (2006). The Russian-born Starshenbaum, who got her start in Russian blockbusters, has the makings of an international star. However, she’s limited to scenes with a costar who doesn’t share her screen presence, shining in a late scene that winks at The Third Man (1949). But there’s no urgency in the central relationship, and the film’s few bedroom scenes feel mechanical.

Although many are quick to take sides in the bloody conflict between Zionists and Palestinians today, Shoshana considers an entangled view of how violence and retaliation escalate until everyone is culpable. While that theme resonates with admirable centrism, the way Winterbottom frames this story through a lifeless central romance makes the point feel like an afterthought. The film’s pacing, accented by an excellent score of bluesy brass and paranoid thriller vibes, keeps one invested from start to finish. But it never entirely comes together into a fully formed work. Maybe it shouldn’t. And perhaps that’s the point.

2.5/4 Stars.

Janet Planet

Janet Planet

Have you ever had a moviegoing experience so distracting and so awful that you question whether you actually saw the movie? That’s how I felt after Janet Planet, a film I think would be unfair to review, given what I was trying to ignore during my screening. If pressed for a reaction, I would rate the film positively and recommend you see it based on what I saw. But it would be irresponsible of me as a critic to provide a review of a movie where I felt frustrated and preoccupied during much of the runtime.

For starters, the auditorium where I saw the film must have been subpar or had technical issues that night. The image looked faded, as though the projectionist had dimmed the light to save on costs (a common practice in theaters today, unfortunately). Granted, playwright Annie Baker, who wrote and directed the film, her first, worked with cinematographer Maria von Hausswolff to deliver a washed-out look to match her 1991 period setting. There’s an intentionally soft appearance to the lighting here that looked extra milky because the projector wasn’t primed. The audio, too, had been turned down. It’s already a very quiet movie, and when paired with this particularly restless festival audience, I struggled to hear about 20% of the dialogue.

Indeed, my wife and I were attacked on all sides by obnoxious patrons. To the right of us, a couple whispered about the plot, shifted in their seats, and repeatedly yawned so loud that it snuffed out the movie’s audio. Behind us, a man continued coughing in the guttural grunt you might hear a bodybuilder make while lifting weights. A man in the seat opposite rustled papers in his backpack, apparently doing some mid-film research. But the most persistent distraction was a young woman in a seat in front of us, who made vocalized reactions to literally every line of dialogue or moment in the film. When some people see a puppy in a movie, they react appropriately and say, “Awww.” This person made charmed vocalizations at everything that happened, no matter how innocuous. The oddest moment was when a character put something in the microwave, prompting another coo of delight from the woman, who apparently has a great fondness for microwaves. Two or three curiously placed murmurs of delight can be ignored, but it becomes maddening when they’re delivered every 20-30 seconds during a film played at the sound of a whisper.

You might say, “Why didn’t you say something?” Let’s imagine that I complained to the theater management about the sound and image, and then I shushed everyone around me. At that point, I would have become the distraction—or at least contributed to it. Rather than add to the problem, I resolved to try my best to focus on the film. Only when I sat down to write a review did I realize doing so would be irresponsible.

But let me tell you this: Julianne Nicholson plays Janet, a bohemian acupuncturist and mother of the 11-year-old Lacy, played by the first-time actor Zoe Ziegler. Lacy spends much of her time in a world unto herself, quietly observing and remarking on what she sees. Lacy also has a possessive bond with her mother that raises eyebrows with the people in Janet’s life, such as her boyfriend Wayne (Will Patton), friend Regina (Sophie Okonedo), and later suitor Avi (Elias Koteas). Set in the summer before Lacy enters sixth grade, the film centers on her realizing that she must not cling so much and allow her mother space.

Nicholson imbues her role with an effortless naturalism that might represent her most substantive performance to date, giving the cutesy-named Janet Planet a humanity that feels messy and equivocal. But it’s Ziegler who offers not so much of a performance as an embodiment and steals the picture with wry observations and lived-in idiosyncrasies. I’m looking forward to spending more time with these characters sometime in the future.

Recommended, but No Rating.

Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Person

Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Person

Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Person is among the best of the recent YA romances involving an awkward adolescent whose particular brand of monstrosity becomes a metaphor for teenage angst, sexual anxiety, or some other relatable emotion. Most romances of this sort prove kitschy or desperately hip, assembled with teenager sensibilities in mind. See everything from the Twilight series to 2013’s Warm Bodies to this year’s Lisa Frankenstein. But Ariane Louis-Seize’s debut feature confronts heavy issues, such as not fitting in or having suicidal thoughts, with the emotional layers of an arthouse film instead of the usual safety net supplied by mainstream alternatives.

Sasha (Sara Montpetit) is the daughter of a vampire family that sees her as “impaired” since she empathizes with her potential victims too much to bite and drink from them. Imagine being born normal in the Addams family, and you get the idea. Though her father (Steve Laplante) remains supportive, her mother (Sophie Cadieux) cracks down, prompting an intervention that will force the youthful 68-year-old Sasha to hunt without relying on a family member. Sasha eventually finds a solution in Paul (Félix-Antoine Bénard), a disturbed and bullied boy who considers ending his life. If Paul wants to die, then Sasha can help without turning him into unwilling prey.

The script by Louis-Seize and Christine Doyon occasionally resembles Let the Right One In (2008) and Byzantium (2013) a little too closely, complete with an outsider teen boy meeting a female vampire who becomes his only friend and defends him from bullies. There’s also a familiar brand of macabre bloodsucker humor reminiscent of What We Do in the Shadows (either the 2014 feature or the great FX series). Still, the film handles the material in a manner where characters come first. Many similarly themed movies tend to get lost in the third act, relying on monster-laden thrills to resolve the character conflicts. Louis-Seize’s quiet and effective movie never sacrifices its low-key charms for genre sensationalism; instead, it makes Sasha and Paul feel like fleshed-out characters who have a complex relationship, existing somewhere between food and friendship.

In the scene where you’ll fall in love with these characters, Paul, who has a perpetually terrified expression, stands in Sasha’s bedroom, hoping to die. She puts on a record of “Emotions” by Brenda Lee, and each of them lets their guard down for an extended shot that’s charming in Paul’s stiff dancing and Sasha’s lost-in-the-moment lip synching. They both feel a relatable sense of first-timer anxiety. With vampires often providing loaded metaphors but rarely delivering them with the tenderness they deserve, Humanist Vampire Seeking Consenting Suicidal Person is a delightful alternative, offering a sweet, funny, and thoughtful version of a familiar story.

3.5/4 Stars.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review