The Definitives

The Devils

Essay by Brian Eggert |

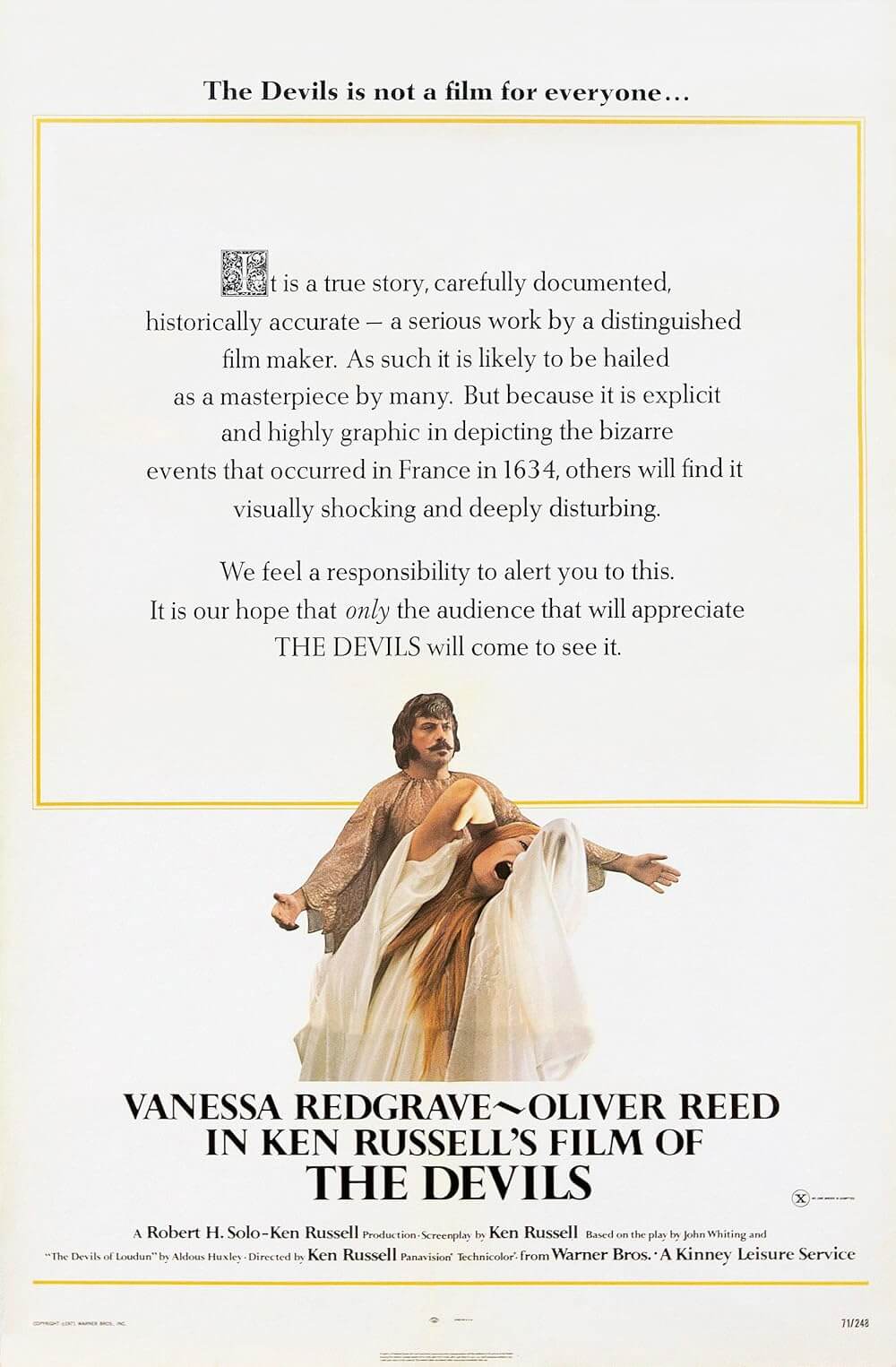

The Devils is the most iconoclastic film ever released by a major Hollywood studio. Director Ken Russell’s urgent masterpiece is overwhelmingly sublime, confronting standards of representation with its many disorienting contrasts: the sacred and profane, the spiritual and material, the sexual and repressed, the beautiful and abject. Russell’s many sensory assaults invite a passionate response, but his layers of history, literary theory, and intellectual critique fuel the picture just as imperatively. Drawing from history’s most infamous, well-documented case of demonic possession that occurred in Loudun, France, in 1634, the British director warns that religious dogma, including sexual repression, can be weaponized by political forces and abused to seize power. In achieving this, The Devils contains an unhinged formal presentation marked by a heightened, Rabelaisian grotesque reality, shown in sensationalistic detail from sexual fervor to demented acts of torture—and often commingling them with religious icons. But along with Russell’s visual excesses, based on actual historical accounts, the film is a vivid affront to the integrity of the church and state. More than its images of medieval exorcism or nuns writhing in demonic ecstasy, it is how Russell critiques and questions the institutions held dear by Western civilization that earned the film its notorious reputation and censorship. What becomes undeniable after watching The Devils is that the viewer has just witnessed the personal vision of a filmmaker unlike any other, and its story, both onscreen and off, remain among the most fascinating and troubling in film history.

The Devils opens with familiar red letters on a black screen that present a disclaimer: “This film is based on historical fact. The principal characters lived and the major events depicted in the film actually took place.” Moviegoers have seen similar words precede historical dramas before, but the film titles are rarely followed with Russell’s genius for charging the screen with visual maximalism, intensified dramaturgy, thematic insight, and tonal buoyancy that push the film’s commentary aside for many viewers. The subject matter’s intersection of religion, politics, sex, possession, hypocrisy, and violence further its potency as a work of art, leaving its historical veracity an afterthought amid its depreciators. Upon its release in 1971, most critics and commentators called the film “outrageous” and “dangerous” and “very sick,” ignoring that the actual events were quite worse. The sheer force of energy and potency of the imagery continues to stun viewers to such an extent that, as of this writing, the film remains under lock and key by Warner Bros., the distributor. From a film history perspective, The Devils is not only masterfully made and wholly unique but also a film maudit (a cursed film) whose behind-the-scenes story, including its journey to and subsequent disappearance from the screen, critical bashing and reassessment, and irrepressible legacy, solidifies its reputation as radical art.

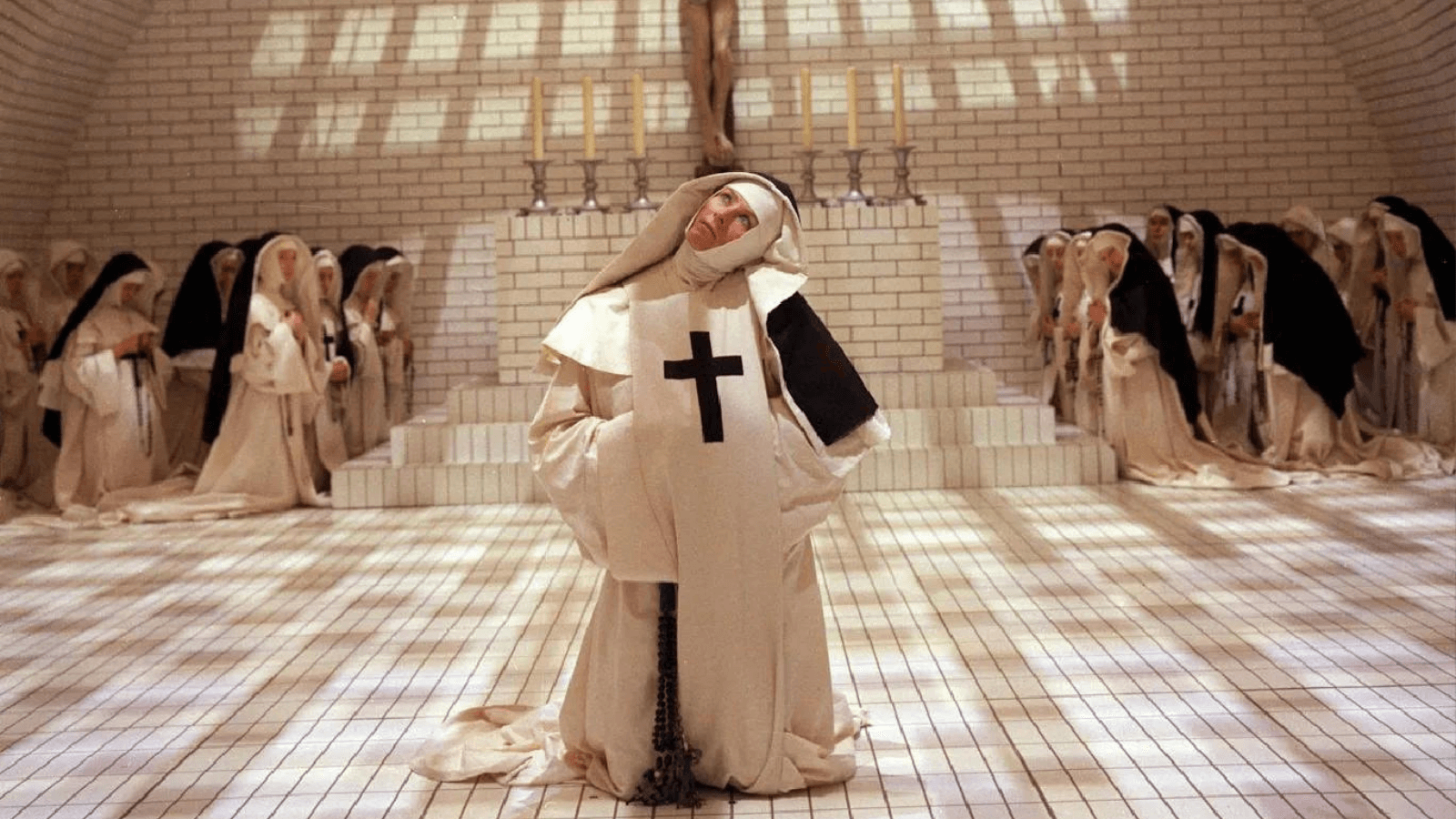

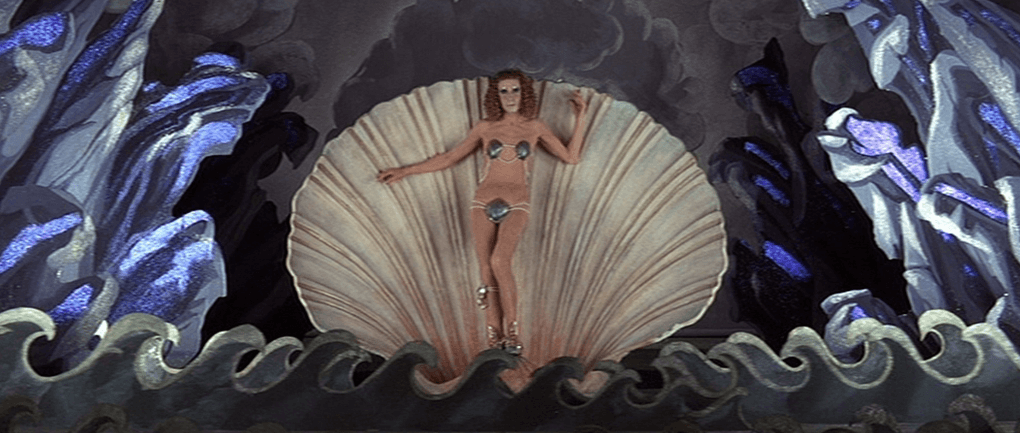

The first images of The Devils welcome the viewer into an aesthetic that would later be recaptured by the chaotic composure of the early scenes in Terry Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988). Indeed, what might be called Gilliamesque in examples spanning from Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) to Tideland (2006) seems to be drawn from Russell’s unruly energy. King Louis XIII (Graham Armitage) puts on a drag show in which he recreates Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus on a stage, albeit with silver shells over his nipples and groin. Wave cutouts shift back and forth, dancers appear on stage in animal costumes, and the King, dressed as Venus, receives a golden crown. Cardinal Richelieu (Christopher Logue) watches from an audience of turned-on and cross-dressing spectators, and he yawningly endures the show, humoring his king while making moves to unify church and state. Richelieu’s sole obstacle is Father Urbain Grandier (Oliver Reed), who has just been appointed a temporary governorship over Loudon, a walled and self-governing city of mostly Protestants whose elected leader recently died. Loudon has remained peaceful throughout France’s holy wars, so the King has promised never to touch one white brick on the city’s walls—a promise that requires Richelieu to engineer a reason for the King to break it.

At this stage, perhaps some background on the facts is warranted: The Devils follows the real-life events that took place in 1634 in Loudun, a city that, even today, is best known for the most infamous account of demon possession ever recorded in history. The event is also the best-documented case from the premodern era, as surviving first-hand accounts paint a clear picture of what happened, what witnesses said, and even what the twenty-seven allegedly possessed nuns experienced. Aldous Huxley’s non-fiction book, The Devils of Loudun, is based on a close study of actual manuscripts, court documents, and diaries from the seventeenth-century incident. Huxley and other historians argue that there were no demonic possessions at Loudun; rather, the beguiled nuns had been manipulated to serve France’s Catholic minister, Richelieu, in a political maneuver to gain control of the self-governed city. Inhabited mainly by Huegenots, whose Protestant beliefs clashed with Richelieu, Loudun was defended by Grandier, who was well-educated in theology and philosophy. By all contemporary accounts, Grandier held a distinct magnetism and seductive energy that earned the admiration of everyone in Loudun. But Grandier was a complex man who could preach “a thundering good sermon,” according to Huxley, even while maintaining a reputation as a ladies’ man (“A man well worth going to hell for,” says one onlooker in The Devils). Grandier enjoyed the social and carnal opportunities that his parsonage afforded him, and he wrote indictments of clerical celibacy and published a scathing text about Richelieu’s dogma. Historians have suggested that Richelieu retaliated against Grandier, using the nuns’ possession as a pretext for gaining control of Loudun and ridding himself of his political enemy.

At this stage, perhaps some background on the facts is warranted: The Devils follows the real-life events that took place in 1634 in Loudun, a city that, even today, is best known for the most infamous account of demon possession ever recorded in history. The event is also the best-documented case from the premodern era, as surviving first-hand accounts paint a clear picture of what happened, what witnesses said, and even what the twenty-seven allegedly possessed nuns experienced. Aldous Huxley’s non-fiction book, The Devils of Loudun, is based on a close study of actual manuscripts, court documents, and diaries from the seventeenth-century incident. Huxley and other historians argue that there were no demonic possessions at Loudun; rather, the beguiled nuns had been manipulated to serve France’s Catholic minister, Richelieu, in a political maneuver to gain control of the self-governed city. Inhabited mainly by Huegenots, whose Protestant beliefs clashed with Richelieu, Loudun was defended by Grandier, who was well-educated in theology and philosophy. By all contemporary accounts, Grandier held a distinct magnetism and seductive energy that earned the admiration of everyone in Loudun. But Grandier was a complex man who could preach “a thundering good sermon,” according to Huxley, even while maintaining a reputation as a ladies’ man (“A man well worth going to hell for,” says one onlooker in The Devils). Grandier enjoyed the social and carnal opportunities that his parsonage afforded him, and he wrote indictments of clerical celibacy and published a scathing text about Richelieu’s dogma. Historians have suggested that Richelieu retaliated against Grandier, using the nuns’ possession as a pretext for gaining control of Loudun and ridding himself of his political enemy.

Among Grandier’s most fervent admirers was Loudun’s Mother Superior, Jeanne des Anges (Joan of the Angels), who grew fixated on Grandier and, in correspondence, asked him to become the spiritual director of her Ursuline convent. Grandier turned down the role and appointed Father Canon Jean Mignon. Under what is presumed to be Father Mignon’s suggestion, Sister Jeanne soon accused Grandier of making a demonic pact to seduce and corrupt her. The other Ursuline nuns confirmed Sister Jeanne’s claims, even though Grandier had never met many of them. Their allegations soon became an opportune political weapon. Around the same time, Richelieu convinced Louis XIII to order the destruction of Loudun’s walls, to be carried out by Baron de Laubardemont. When Laubardemont failed in his mission due to Loudun’s local militia, backed by Grandier, he reported the situation and included the claims of the Ursuline nuns. Laubardemont was then ordered to investigate the so-called possessions and hired witch hunters to exorcize the nuns and look into Grandier. Sister Jeanne and the nuns put on a show so convincing that Grandier was soon arrested. Huxley and other historians insist the nuns behaved out of a mass psychogenic illness (commonly known as mass hysteria) compelled by repressed emotions and sexual desires, and in the case of Sister Jeanne, a touch of madness.

Father Mignon oversaw the series of public exorcisms, which served as exhibitions of debauched behavior from nuns who drew crowds from all over France with their animalistic, writhing performances—all of which they attributed to Father Grandier’s influence. Sister Jeanne claimed that Grandier had tossed a bouquet of roses over the convent walls, and with it, conjured two demons, Asmodeus and Zabulon. Subjected to interrogation and horrific torture, Grandier refused to confess or confirm the nuns’ claims. After a supposed contract between himself and Lucifer—likely forged by Sister Jeanne—was presented as evidence, Grandier was burned at the stake. But the nuns’ performance did not end with Grandier’s death. They continued until 1637, drawing crowds from around Europe that wanted to see the possessed nuns bark and spit, contort their bodies, and perform spider walks—a kind of freak show exhibition that the Catholic Church backed. The sideshow attraction brought significant commerce to Loudun that helped the convent thrive during plague times. Sister Jeanne even achieved celebrity status in France and dined with the king and queen. Eventually, Richelieu ordered the exorcisms to stop, having achieved his goal of overtaking Loudun and making Grandier a political patsy. Sister Jeanne faded into obscurity. In her remaining years, she claimed to have been visited by the occasional angel and demon, attempted suicide more than once, and in the end, became delegitimized by a public that called her a witch. She died in 1665.

Another filmmaker may have adapted this ghastly page of history into a stately period piece. Not Ken Russell. But before exploring his extravagant, outrageous, and uninhibited production, it’s necessary to understand the director’s background to appreciate his influence on The Devils. Born in 1927 in Southampton, England, Russell spent much of his youth in the cinema, his refuge from his volatile home life and mentally ill mother. After brief stints in the Merchant Navy and RAF, and then failing to become a ballet dancer, Russell took up photography in his late twenties, hoping it would lead him to filmmaking. Along with his first wife, fashion and costume designer Shirley Russell, he created several photographic essays that landed him a job at BBC Television. There, Russell would make his first short films as well as hour-long episodes of Monitor, a program about artists that would provide a start to other filmmakers, such as John Schlesinger (Billy Liar, 1963). Monitor also led Russell to his first collaboration with Oliver Reed for a 1965 segment called The Debussy Film. The director made dozens of short subject films and television episodes at the BBC between 1959 and 1970, earning a reputation for eccentric subjects executed with avant-garde techniques. From this early starting point, Russell concentrated on unconventional modes of representation, emphasizing grotesque bodies, iconoclastic juxtapositions, and his love for Romantic composers.

Another filmmaker may have adapted this ghastly page of history into a stately period piece. Not Ken Russell. But before exploring his extravagant, outrageous, and uninhibited production, it’s necessary to understand the director’s background to appreciate his influence on The Devils. Born in 1927 in Southampton, England, Russell spent much of his youth in the cinema, his refuge from his volatile home life and mentally ill mother. After brief stints in the Merchant Navy and RAF, and then failing to become a ballet dancer, Russell took up photography in his late twenties, hoping it would lead him to filmmaking. Along with his first wife, fashion and costume designer Shirley Russell, he created several photographic essays that landed him a job at BBC Television. There, Russell would make his first short films as well as hour-long episodes of Monitor, a program about artists that would provide a start to other filmmakers, such as John Schlesinger (Billy Liar, 1963). Monitor also led Russell to his first collaboration with Oliver Reed for a 1965 segment called The Debussy Film. The director made dozens of short subject films and television episodes at the BBC between 1959 and 1970, earning a reputation for eccentric subjects executed with avant-garde techniques. From this early starting point, Russell concentrated on unconventional modes of representation, emphasizing grotesque bodies, iconoclastic juxtapositions, and his love for Romantic composers.

During this time, Russell directed several documentaries for the BBC, including Isadora Duncan, The Biggest Dancer in the World (1966); Dante’s Inferno (1967), about artist and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti; and Song of Summer (1968), about composers Frederick Delius and Eric Fenby. Far from standard televised programs, Russell’s documentaries defy the usual limits, using pronounced reenactments and dramatic staging to achieve something that tests the boundaries of the already nebulous definitions of the documentary—a dynamic he also demonstrated on Lisztomania (1975), his film about composer Franz Liszt. In his final documentary film for the BBC, Dance of the Seven Veils (1970), which portrayed composer Richard Strauss (dancer Christopher Gable) as a Nazi, an extended sequence features Strauss chased by nuns writhing in ecstasy—a sequence that mirrors several scenes in The Devils—and it, too, was banned from television. Throughout his BBC years, Russell occasionally stepped away to make feature films, including his debut, the saucy comedy French Dressing (1964), and the more significant and acclaimed Women in Love (1969). Russell remained with the BBC until 1970, and his experiences there under tight budgets and strict deadlines meant he could work fast under pressure. In 1971 alone, he directed three feature films: The Music Lovers, The Devils, and The Boy Friend. That Russell made a film as complex, challenging, and visually loaded as The Devils alongside two others in the same year speaks to the director’s renegade momentum during this period. And, given his record up to 1971 of translating historical and biographical subjects in unconventional ways, it’s no wonder The Devils became such an unorthodox film.

Russell’s particular method and brand of talent has disappeared, which is to say, it could not exist today, perhaps with good reason. Since his death in 2011, his penchant for films about sexual liberation, savage violence, outlandish humor, and taboo subject matter is matched only by his lasting reputation. Russell’s anti-authority, anti-establishment mindset earned him the label of a volatile genius among those who worked with him. Director Michael Powell called him a “lovely monster.” Many accounts describe him as a petulant child, shouting obscenities, throwing temper tantrums, and exploding on the set in a manner that would never be tolerated now. Nor was he an actor’s director; he did not explain motivations or give line readings, and he expected his actors to arrive for work prepared. Instead, Russell blasted loud music on the set to create the mood he wanted for the actors, and he shot many takes in search of spontaneity—the X-factor in every Russell film. His default mode was excess. Whatever his methods, the wildly original approach made him incomparable and copied by the likes of those, such as Terry Gilliam, brave enough to borrow from him. The criticisms against Russell’s authorial signatures use words like “trashy” and “obscene” and “overwrought” to describe his persistent examination of transgressive themes. Others consider him an incomparable original. In Phallic Frenzy, Joseph Lanza’s book about the director, the author observes that Russell is “cinema’s true rogue, a human moviola who pisses and ejaculates tales of gods and devils, love and lust, sex and death, inspiration and melancholia.”

The Devils is Russell’s magnum opus. Murray Melvin, who plays Father Mignon in the film, told author Richard Crouse, “I’ve always thought the movie summed up Ken. When you read the actual Huxley book, it is a man against the establishment. If there was ever a parallel with Ken [that’s it].” But like many of Russell’s films, The Devils is an adaptation of an existing text; two of them, in fact. Much of The Devils draws from Huxley’s 1952 book—a work of historical non-fiction that explores the incident in vast detail from recorded evidence. Huxley also spends many pages exploring the philosophical underpinnings of the era. The author intended his text to be a template for using history as a framework to understand modern-day ideas and events; expressly, he implied historical parallels between the Loudun case, the Red Scare, and McCarthyism. Huxley’s book, well-received but never as popular as his later novel Brave New World, inspired Sir Peter Hall of the Royal Shakespeare Company to enlist playwright John Whiting to write a 1961 adaptation for the stage called The Devils. Whiting took artistic liberties with the facts, condensing timelines and creating composite characters, but the play became a critical and financial success. The same year as Whiting’s play, Polish filmmaker Jerzy Kawalerowicz released Matka Joanna od Aniołów (Mother Joan of the Angels), a black-and-white art film that takes place after Grandier’s execution and involves a priest (Mieczyslaw Vojt) who attempts to save Sister Joan (Lucyna Winnicka) with the power of love. Whiting inspired another Polish artist, composer Krzysztof Penderecki, to write an opera based on the play, titled The Devils of Loudun, which debuted in 1969 at the Hamburg State Opera and became a European hit.

The Devils is Russell’s magnum opus. Murray Melvin, who plays Father Mignon in the film, told author Richard Crouse, “I’ve always thought the movie summed up Ken. When you read the actual Huxley book, it is a man against the establishment. If there was ever a parallel with Ken [that’s it].” But like many of Russell’s films, The Devils is an adaptation of an existing text; two of them, in fact. Much of The Devils draws from Huxley’s 1952 book—a work of historical non-fiction that explores the incident in vast detail from recorded evidence. Huxley also spends many pages exploring the philosophical underpinnings of the era. The author intended his text to be a template for using history as a framework to understand modern-day ideas and events; expressly, he implied historical parallels between the Loudun case, the Red Scare, and McCarthyism. Huxley’s book, well-received but never as popular as his later novel Brave New World, inspired Sir Peter Hall of the Royal Shakespeare Company to enlist playwright John Whiting to write a 1961 adaptation for the stage called The Devils. Whiting took artistic liberties with the facts, condensing timelines and creating composite characters, but the play became a critical and financial success. The same year as Whiting’s play, Polish filmmaker Jerzy Kawalerowicz released Matka Joanna od Aniołów (Mother Joan of the Angels), a black-and-white art film that takes place after Grandier’s execution and involves a priest (Mieczyslaw Vojt) who attempts to save Sister Joan (Lucyna Winnicka) with the power of love. Whiting inspired another Polish artist, composer Krzysztof Penderecki, to write an opera based on the play, titled The Devils of Loudun, which debuted in 1969 at the Hamburg State Opera and became a European hit.

Although other artists had adapted the material in several distinct interpretations, none would stand up to Russell’s eventual film. The director knew he wanted to translate Huxley’s book to the screen the moment he read it. Russell told film critic Mark Kermode, “When I first read the story I was knocked out by it—It was just so shocking!—and I wanted others to be knocked out by it too.” He had seen the play and Kawalerowicz’s film. Still, he felt his status as a Catholic, which soon lapsed (“The Devils was the last nail in the coffin of my Catholic faith,” Russell said), would provide him the necessary outlook to distinguish and emphasize the strange behavior of the nuns and bizarre rituals of the witch hunt from a Catholic perspective. Fortunately, Russell’s Women in Love proved a financial win for United Artists, so they agreed when the director pitched them to adapt the story into a feature film. Relying heavily on both Huxley’s book and “about a third” from Whiting’s play, Russell began pre-production, with experimental filmmaker and stage designer Derek Jarman building the stunning sets. Huxley had long expressed reservations about any adaptation of his book. Before his death in 1963, the author wrote to his son about the prospects of turning his book into a movie: “What on earth will they make out of it? I feel a great deal of curiosity and apprehension.” Sure enough, when the executives at United Artists finally got around to reading Russell’s script, they had apprehensions too—so many that they backed out of the project. It took four months of shopping the production around to other studios before Warner Bros., for better or worse, agreed to pick up the film.

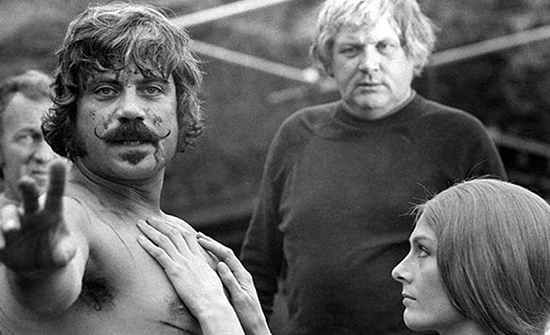

When Russell set out to cast The Devils, Oliver Reed was his only choice to play Grandier. Reed’s reputation was that of a disciplined actor on the set, but his well-known exploits as an indulgent drinker, volatile fighter, and womanizer on weekends away from his current movie shoot mirrored Grandier’s duality. “Both are complex, deeply flawed men whose appetites overshadowed their accomplishments,” wrote Crouse. Moreover, Russell’s earlier collaborations with Reed, including Monitor episodes and Women in Love, confirmed that the actor would be willing to go as far as his director needed. The same was true of Vanessa Redgrave, Russell’s second choice to play Sister Jeanne, after Glenda Jackson—the star of Women in Love. But, unfortunately, Jackson backed out of the production after playing one too many “neurotics” for Russell, including a role as Tchaikovsky’s wife in The Music Lovers. So the director turned to Redgrave, who was already known for her sometimes controversial political activism and acclaimed performance in Blow-Up (1966)—and her willingness to go against the mainstream no doubt interested Russell. For her performance as Sister Jeanne, Redgrave unleashes a wild character who has given over to her every impulse, achieved in her sharp, uninhibited laughs and physical contortions that raze the theological integrity of the screen nun.

In directing the film, Russell establishes a disorienting aesthetic and political commentary with The Devils’ first images. The opening shots of Louis XIII’s drag show convey a topsy-turvy world of grotesque surprise and performance with a scene of nonconformist sexuality, and the motif spreads from the royal court down through the church. Its libertines act out crude and cruel vaudeville routines, such as shooting a Huguenot dressed as a blackbird, while salacious humor and horror propel the nun sideshow and Grandier’s trial. Underneath Russell’s crazed worlds, there are political machinations at work, creating the film’s most essential contrasts: Louis XIII’s appearance stands in direct opposition to Cardinal Richelieu, whose dogmatism epitomizes the norm against which Grandier and every subversion in the film operate. Grandier’s appointment as Loudun’s figurehead means he defends its autonomy against Richelieu’s desire for national unity; he protests against Richelieu’s officer, Baron De Laubardemont (Dudley Sutton), whom Grandier prevents from demolishing Loudun’s white walls. He seeks religious tolerance, defending Protestants from Richelieu’s systemic persecution. Against the Richelieu standard, characterized as stifling and cruelly Catholic, the film presents no end of abnormalities, from libidinous desire to the grim sights of the plague. Inside the Ursuline convent, a space Jarman reportedly designed with the clean geometric order of a public bathroom, Sister Jeanne’s warped body indicates that all is not well. Outside, amid the plague, complete with piles of burning corpses and the miasma of smoke billowing through the night, death is normalized in Loudun. So when it comes time for the public exhibition of Grandier’s cruel fate, the scene doesn’t seem so out of the ordinary around such pervading death.

In directing the film, Russell establishes a disorienting aesthetic and political commentary with The Devils’ first images. The opening shots of Louis XIII’s drag show convey a topsy-turvy world of grotesque surprise and performance with a scene of nonconformist sexuality, and the motif spreads from the royal court down through the church. Its libertines act out crude and cruel vaudeville routines, such as shooting a Huguenot dressed as a blackbird, while salacious humor and horror propel the nun sideshow and Grandier’s trial. Underneath Russell’s crazed worlds, there are political machinations at work, creating the film’s most essential contrasts: Louis XIII’s appearance stands in direct opposition to Cardinal Richelieu, whose dogmatism epitomizes the norm against which Grandier and every subversion in the film operate. Grandier’s appointment as Loudun’s figurehead means he defends its autonomy against Richelieu’s desire for national unity; he protests against Richelieu’s officer, Baron De Laubardemont (Dudley Sutton), whom Grandier prevents from demolishing Loudun’s white walls. He seeks religious tolerance, defending Protestants from Richelieu’s systemic persecution. Against the Richelieu standard, characterized as stifling and cruelly Catholic, the film presents no end of abnormalities, from libidinous desire to the grim sights of the plague. Inside the Ursuline convent, a space Jarman reportedly designed with the clean geometric order of a public bathroom, Sister Jeanne’s warped body indicates that all is not well. Outside, amid the plague, complete with piles of burning corpses and the miasma of smoke billowing through the night, death is normalized in Loudun. So when it comes time for the public exhibition of Grandier’s cruel fate, the scene doesn’t seem so out of the ordinary around such pervading death.

The theoretical origins of Russell’s project of grotesque representation can be understood through Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin’s Rabelais and His World from 1968, a study of Renaissance-era writer François Rabelais, whose pentalogy The Life of Gargantua and of Pantagruel (1532-1564)—which Russell considered making in the early 1970s after The Devils—contained the seeds of grotesque realism. The term grotesque (originally grottesca) had only been coined a century before Rabelais’ time and was used to describe the ornamentation on Roman baths (grotta) that often portrayed an interweaving of human and animal forms. Bakhtin redefines the term and cites its origins in folk culture; specifically, its relation to carnival and festival imagery. He also charts the term’s shift from the classical understanding of the grotesque to “a gross violation of natural forms and proportions.” Trivial and base subjects, monstrous masks worn during carnival festivities, or warped gargoyle faces on the exterior of holy structures and the margins of holy books contorted the limits of human-animal physicality, marking excesses that violate the platforms of decorum and good taste. Whereas classical standards portray ideal bodies and avoid the distorted or lower functions of the body and consider them unfit for portrayal, the grotesque welcomes, through a defiant realism, the base reality of all that is not classically beautiful in mimetic art. Representations of so-called lecherous behavior and states of being—usually relating excessive drunkenness, sexual acts, scatology, and deformity—were passed around in popular etchings, folk tales, and fine artwork. What started on the fringes of cultural acceptance, embraced by popular Medieval and peasant culture, soon merged with court culture to become more widely accepted by artists from Hieronymus Bosch to Pieter Breugel the Elder, and thus the royal courts who commissioned their works.

Although the grotesque’s origins reside in a lower form of representation, Bakhtin argues for its value as a reflector of everyday life and culture, and, further, as a vital source of humanism that offers an alternative to idealized forms of classical mimesis. Grotesque images in art, therefore, have a paradoxical significance. Bakhtin notes the origins of grotesque imagery as acts of subversion, specifically through mocking or indecent laughter, renderings of the human body that defy standards of decency, and perhaps most importantly, parodic characterizations of authority. He also sees the grotesque as realistic in its frank acceptance of naturalism and the material body. From the early Renaissance until the eighteenth century, it was dismissed as “gross naturalism” among tastemakers, but Bakhtin redefines the term with the positive “grotesque realism,” which equalizes the ideal and the earthly. Later assessments have recognized the ironic beauty of the grotesque, as it acknowledges that life exists in all manner of degrees, from the lowest and primitive form of our physical selves to the idealized and most spiritual notions informed by religious dogma. Though classical canons attempt to set aside and remove those elements deemed unfit for respectable conversation and depiction in art, the grotesque seeks to accept and unify the excluded components with their higher counterparts through degradation. Thus, the grotesque subverts by accepting life as a series of material, even base realities inseparable from more intangible and idealistic ambitions. The two must, inevitably, coexist.

What this theoretical discussion of the grotesque reveals about The Devils is Russell’s interest in the relationship and violent, even comical, disparities between the material reality of his characters and their devotional belief systems. Although Russell’s interest in the story is political in its cynicism toward powerful institutions, its grotesqueness constitutes such an embodiment of abject reality that it has prompted critics such as Kermode and many others to describe The Devils as a horror film. Grandier occupies the grotesque’s clash of devotional and earthly drives, the opposition of the spiritual with the raw physical reality of his carnal desires. Sister Jeanne, too, remains rapt by desire and so bound to those feelings that they distort her piousness. With her head cocked to the side at almost the same angle as the crucified Christ, and her contorted, hunchback body, she would be right at home in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s grotesque oil painting The Beggars from 1568, next to the limping and twisted figures who confront the base reality rarely shown in Renaissance art. Furthermore, Russell underlines morbid scenes from Huxley’s book with a dark sense of humor, such as when two inquisitors investigate Sister Jeanne by analyzing her vomit. This practice, sanctioned by the Catholic Church, turns into a backward holy procedure carried out not by trained exorcists but by two apothecary scientists who make assumptions about what they see: a piece of meat that looks like “the heart of a child,” the blood of a man, some stuff that “could only be semen,” and in Russell’s most ironic joke, “a carrot.”

What this theoretical discussion of the grotesque reveals about The Devils is Russell’s interest in the relationship and violent, even comical, disparities between the material reality of his characters and their devotional belief systems. Although Russell’s interest in the story is political in its cynicism toward powerful institutions, its grotesqueness constitutes such an embodiment of abject reality that it has prompted critics such as Kermode and many others to describe The Devils as a horror film. Grandier occupies the grotesque’s clash of devotional and earthly drives, the opposition of the spiritual with the raw physical reality of his carnal desires. Sister Jeanne, too, remains rapt by desire and so bound to those feelings that they distort her piousness. With her head cocked to the side at almost the same angle as the crucified Christ, and her contorted, hunchback body, she would be right at home in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s grotesque oil painting The Beggars from 1568, next to the limping and twisted figures who confront the base reality rarely shown in Renaissance art. Furthermore, Russell underlines morbid scenes from Huxley’s book with a dark sense of humor, such as when two inquisitors investigate Sister Jeanne by analyzing her vomit. This practice, sanctioned by the Catholic Church, turns into a backward holy procedure carried out not by trained exorcists but by two apothecary scientists who make assumptions about what they see: a piece of meat that looks like “the heart of a child,” the blood of a man, some stuff that “could only be semen,” and in Russell’s most ironic joke, “a carrot.”

Russell explained that the vomit analysis scene included one of many “deliberate ludicrous touches throughout the film, designed to point out the nonsensical irony of these horrors being committed in the name of God.” Most of the horrors inflicted on Grandier use religion as a pretense for revenge over some earlier, comparatively minor slight. The film’s initial scenes find Grandier making enemies: He scolds the two apothecary scientists, a chemist and a surgeon, for using backward experiments on plague victims. He angers Father Mignon’s cousin, Louis Trincant (John Woodvine), by impregnating Trincant’s daughter Philippe (Georgina Hale) and refusing to take responsibility for the child. And he aggravates Father Mignon, who is spiteful because Grandier flaunts his freedoms yet remains well-liked in Loudun, evidenced in an early moment when two altar boys rush to keep Grandier’s garments out of the mud but pay no attention to Mignon. Grandier also believes there’s no law of God saying he cannot marry, so in secret, he marries himself to Madeleine (Gemma Jones), a young woman who’s alone after the plague takes her family. Sister Jeanne is filled with jealous rage by the rumor of Grandier’s irregular marriage and wants him punished. These personal slights and petty sins become the motivation needed to accuse and evidence to verify the likelihood of Grandier’s demonic corruption of the Ursulines.

Russell continues his grotesque agenda when he visualizes Sister Jeanne’s sexual fantasies and, in doing so, confronts the taboo of mixing sexuality and religious icons. In another filmmaker’s hands, the sequences might have either been toned down or engaged in nunsploitation, but Russell never approaches eroticism—he includes these scenes in a commentary on the dangers of sexual repression, especially when filtered through religious fervor. Sister Jeanne’s repressed desires dream up Grandier as Christ, walking on water, until she, serving as Mary Magdalene, dries his feet with her hair. Later, Grandier appears to her on the cross in monochrome, recalling Cecil B. DeMille’s religious epic, King of Kings (1927). He descends, and she licks his wound from the Holy Lance before rolling around with him in the mud. Finally, Sister Jeanne resorts to self-harm to end her fantasies, flagellating herself with a cat ‘o nine tails. What is so offensive about these moments to some is how Russell inhabits Sister Jeanne’s perspective and, therein, sexualizes an inherently holy image to capture a deranged point of view. The film’s detractors, and its many censors, see only the images at face value, not the meaning contained within them. Of course, Russell intends to provoke his audience with scenes of the Ursulines acting out a mock wedding ceremony between themselves and Grandier, and the nun who appears turned on when she spies Sister Jeanne masturbating and self-flagellating. But while Sister Jeanne maintains a sexual obsession with Grandier, she also projects her insecurities about her malformed appearance onto Grandier and blames him for her evil and sexual thoughts. Although she scorns the other nuns for looking at Grandier during a street procession, she then crawls to get a glimpse, writhing with pleasure at the sight of him.

Sister Jeanne is one of Russell’s many hypocritical characters in The Devils, a film rife with ideological hypocrisy that materializes in countless horrors. Take Father Barre (Michael Gothard), who Laubardemont enlists to perform the exorcisms. Russell borrowed Barre’s look, complete with long hair and wire-rimmed glasses, from John Lennon, but presents him with the cult leader energy of Charles Manson. Barre uses his authority to manipulate and exploit his subjects, claiming that Sister Jeanne and the other nuns have been infected by evil and that “sin can be caught as easily as the plague.” Barre abuses his power to brainwash the nuns into believing his agenda on the pretense of saving their souls. They act out like Beatlemaniacs because of his claim, partly to survive but also because Barre is a church-appointed witch hunter, so his claims must be true. Together with Laubardemont, Mignon and Barre know their accusations are false and that, compelled by Richelieu, they have tormented the Ursulines to reinforce their political position and gain certain hierarchical advantages. But what’s most vile about them is how petty and exploitative they are about their hypocrisy. Mignon and Barre watch Grandier’s leg-shattering torture by the boot with a perverse satisfaction, while Laubardemont taunts him: “Tell me, do you love the church?” Grandier can only reply honestly, “Not today.” And when they force Grandier to crawl to the site where he’ll be burned alive, Mignon and Barre kick him with petty torments.

Sister Jeanne is one of Russell’s many hypocritical characters in The Devils, a film rife with ideological hypocrisy that materializes in countless horrors. Take Father Barre (Michael Gothard), who Laubardemont enlists to perform the exorcisms. Russell borrowed Barre’s look, complete with long hair and wire-rimmed glasses, from John Lennon, but presents him with the cult leader energy of Charles Manson. Barre uses his authority to manipulate and exploit his subjects, claiming that Sister Jeanne and the other nuns have been infected by evil and that “sin can be caught as easily as the plague.” Barre abuses his power to brainwash the nuns into believing his agenda on the pretense of saving their souls. They act out like Beatlemaniacs because of his claim, partly to survive but also because Barre is a church-appointed witch hunter, so his claims must be true. Together with Laubardemont, Mignon and Barre know their accusations are false and that, compelled by Richelieu, they have tormented the Ursulines to reinforce their political position and gain certain hierarchical advantages. But what’s most vile about them is how petty and exploitative they are about their hypocrisy. Mignon and Barre watch Grandier’s leg-shattering torture by the boot with a perverse satisfaction, while Laubardemont taunts him: “Tell me, do you love the church?” Grandier can only reply honestly, “Not today.” And when they force Grandier to crawl to the site where he’ll be burned alive, Mignon and Barre kick him with petty torments.

Note also how Barre’s zealotry is guided by his basest desires. He listens with morbid glee to Sister Jeanne’s account of the night Grandier and “six of his creatures” formed an “obscene altar,” and he delights in forcing enemas, vaginal and otherwise, to expose the demons lurking in her body. Huxley suggests Barre was overly committed, and Russell shows Barre using his dogma to feed his carnality: After the worst of the exorcism, Barre claims he must climb atop Sister Jeanne to rape the devils out of her. Huxley compared Barre’s exorcism of Sister Jeanne to “the equivalent, more or less, of a rape in a public lavatory.” Laubardemont’s hypocrisy goes even further after Grandier’s death; he doesn’t even try to disguise that the entire exorcism has been a political show. Instead, Laubardemont tells Sister Jeanne, “With Grandier gone, you are sane,” and gives her a souvenir that survived the fire: a chunk of his femur, which resembles male genitalia. Among the most unsettling hypocrisies exposed by The Devils is the crowd, which acknowledges that Barre has deliberately provoked the nuns and used torturous means to procure, even force, their confessions, but members of the crowd snicker at the scene anyway. Despite their awareness of the corrupt situation, the people want a show to distract them from the plague. So rather than accept the fallacies of human beings—even priests—and exercise some Christian forgiveness, the bloodthirsty mob calls for the vilest expiation. Only later, with Grandier on the stake, does the rollicking crowd call out Mignon as a “Judas” with some moral certainty.

By contrast, Grandier acknowledges his hypocrisy with a sense of self-awareness, which makes him somehow heroic in The Devils’ roster of vile and corrupt characters. Of course, Grandier is not a morally untarnished protagonist; he’s complicated, often well-meaning, but also deeply flawed. He’s an uneasy protagonist in a film that also challenges the integrity of political and religious leaders, devoted servants of the church, and the church itself. While on trial, his confessions to comparatively minor sins of the flesh result in some of Reed’s finest acting and some of Russell’s greatest screenwriting. “I have been a man. I have loved women. I have enjoyed power,” Grandier announces, which is more than his sanctimonious accusers would ever admit. Alas, Grandier’s sense of his sinful behavior leads to a self-destructive streak. He tests the limits of his authority and mortality by yearning for his demise in hopes of being “reunited with God.” In this, Grandier is presented as wise and rational, if a tempted man who also seems to be the only sane person in this film’s insane world. “Call me vain and proud, the greatest sinner ever to walk God’s earth,” he announces. “But Satan’s boy I could never be. I haven’t the humility.”

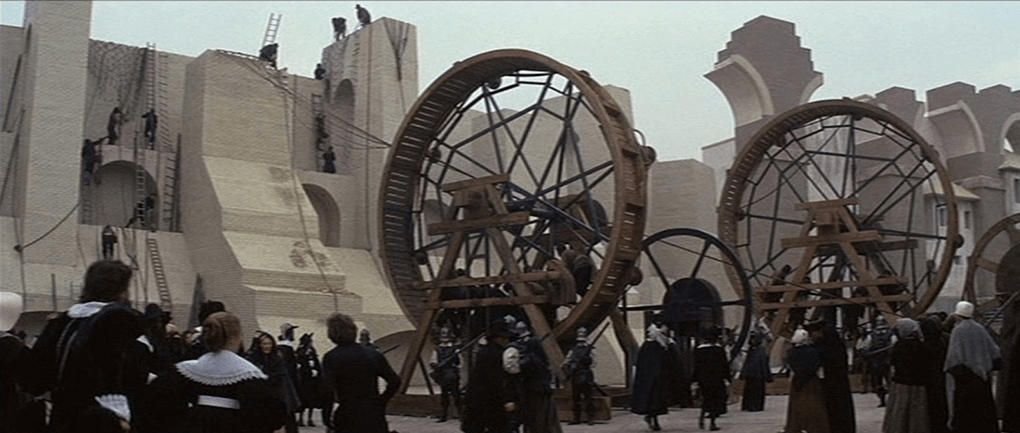

The Devils overflows with personal and political duplicity, sexual outbursts, horrific torture, and officiated madness, and Russell orchestrates everything onscreen with a masterful touch. The director’s use of warped angles, rushing camerawork, wide lenses, and expressive sets and performances make the film an agitated and beautifully constructed piece of filmmaking. Consider the intentionally anachronistic sets, made by Jarman in a manner that differs from the standard sets of crumbling stone that moviegoers often see in period pieces. Jarman invented sets that may not have been historically accurate but looked appropriately intact for the period. Jarman’s antiseptic-white spaces inside of Loudun, some of the largest sets ever built at that time, were designed to look contemporary for the characters—just as glorious as they would have been in 1634, not illogically old and crumbling. The newness and cleanness of Jarman’s unconventional and almost futuristic designs add to the final moments of The Devils, when, upon the moment of Grandier’s death, Laubardemont orders the bright walls of Loudun detonated. If the nuns’ exploitation and Grandier’s show trial and execution were not enough, Loudun loses not only its city’s beloved leader but its walls, thus its independence inside France, in a tragic turn. The final shot follows Grandier’s widow, Madeleine, leaving Loudun over the remains of the ruined wall, down a road lined with skeletons tied to breaking wheels.

The Devils overflows with personal and political duplicity, sexual outbursts, horrific torture, and officiated madness, and Russell orchestrates everything onscreen with a masterful touch. The director’s use of warped angles, rushing camerawork, wide lenses, and expressive sets and performances make the film an agitated and beautifully constructed piece of filmmaking. Consider the intentionally anachronistic sets, made by Jarman in a manner that differs from the standard sets of crumbling stone that moviegoers often see in period pieces. Jarman invented sets that may not have been historically accurate but looked appropriately intact for the period. Jarman’s antiseptic-white spaces inside of Loudun, some of the largest sets ever built at that time, were designed to look contemporary for the characters—just as glorious as they would have been in 1634, not illogically old and crumbling. The newness and cleanness of Jarman’s unconventional and almost futuristic designs add to the final moments of The Devils, when, upon the moment of Grandier’s death, Laubardemont orders the bright walls of Loudun detonated. If the nuns’ exploitation and Grandier’s show trial and execution were not enough, Loudun loses not only its city’s beloved leader but its walls, thus its independence inside France, in a tragic turn. The final shot follows Grandier’s widow, Madeleine, leaving Loudun over the remains of the ruined wall, down a road lined with skeletons tied to breaking wheels.

Russell alternates between two pronounced visual forms in The Devils. A full spectrum of colors appears in the earlier, more theatrical scenes at court or those inside Grandier’s home, littered with books and artwork. Elsewhere, inside the Ursuline convent and scenes involving Grandier’s trial and torture, the colors have been stripped down to black and white holy spaces invaded by flesh tones. With the latter section, Russell embraces the grotesque, making the most of viscera, bodily fluids, and both the natural and unnatural forms of the body. He delights in revealing flesh during bedroom scenes between Grandier and Philippe. Still, he treats the undulating bodies of nuns and Sister Jeanne’s many distortions, from the self-inflicted to the possessed, with equal enthusiasm. Along with editor Michael Bradsell, Russell creates an innately musical visual rhythm, informed by the director’s obsession with composers and various experiments with the musical genre, from The Boy Friend to Tommy (1975). However, the musical, visual rhythms echo Peter Maxwell Davies’ discordant score to create an aural assault—a contrast between the clean white walls of the nunnery and the serene spaces of the church with the horrific behaviors shown therein. As Jack Kroll observed about Lisztomania in Newsweek, “Russell’s gimmicks may be crazily burlesque, but they burlesque historical truth.” Indeed, the scenes of exorcism, Grandier’s torture and burning at the stake, and orgiastic behaviors from nuns may prove revolting but are no less a matter of historical fact.

Regardless of how over-the-top The Devils may seem at times, Russell demonstrates a tonal understanding of every scene in visual terms. For example, observe the simple composition of a scene between Grandier and his lover in bed. The moment is earnest, presented in an unfussy and low-key manner, “like an exquisite Japanese print,” notes critic Jack Fisher. But because most of the film involves tormented characters in situations of moral, political, or personal corruption, much of Russell’s treatment employs sharp visual metaphors. Nothing could be more apt than Sister Jeanne’s asymmetrical body that creates a visual distortion in the otherwise orderly Ursuline convent. There, the uniform black habits contrast the white tiles and clean, lifeless, geometrical rooms, which have been designed to suppress stimulus and encourage worship. Inside, Sister Jeanne’s warped spine and perspective are further symbolized by her appearance behind the narrow grate from where she peers out to steal a glimpse of Grandier, her sexual fantasy. The grate is located in an isolated crawl space, hidden and away from the other Ursuline nuns, and along with her hunched back, Russell’s visual treatment of Sister Jeanne’s appearance behind bars captures her inner conflict and repressed desire clashing with her faith. Part of what makes The Devils such a jarring experience is Russell’s series of visual and thematic contrasts, which perfectly encapsulate his ideas about the point at which earthly reality collides with repressive religious and state idealism.

However, the scenes that proved most offensive to the film’s critics were those without metaphor, where the raw content proved innately offensive to their belief systems and the dignity they associate with religious icons and representational decency. For instance, when Sister Jeanne dreams of rolling in the mud with Grandier, who appears to her in a Christlike fashion, complete with a crown of thorns, the sexualization of revered Christian imagery proves scandalous for the religiously inclined. The same is true of the nuns who are exorcized by the backward doctors who use boiling water to perform vaginal irrigation—an unthinkably vile detail drawn from the actual history of the Loudun case. The film’s most notorious sequence, removed from most surviving copies by the studio and censors, is the “Rape of Christ” sequence. In the two-minute sequence, naked, orgasmic nuns pull down a massive statue of Jesus and begin rubbing themselves on its face, hands, and groin. Another nun gratifies herself with a candle. The sight of undulating bodies in ecstasy prompts Father Mignon to begin feverishly masturbating. The whole sequence underscores the film’s theme of religious, sexual, and political hypocrisy in an unruly two minutes of screen time. And while it’s a shame the sequence was cut against the director’s wishes, Russell’s zoom-in-and-zoom-out technique, which suggests masturbation, proves to be a broad visual touch that The Devils may be better without.

However, the scenes that proved most offensive to the film’s critics were those without metaphor, where the raw content proved innately offensive to their belief systems and the dignity they associate with religious icons and representational decency. For instance, when Sister Jeanne dreams of rolling in the mud with Grandier, who appears to her in a Christlike fashion, complete with a crown of thorns, the sexualization of revered Christian imagery proves scandalous for the religiously inclined. The same is true of the nuns who are exorcized by the backward doctors who use boiling water to perform vaginal irrigation—an unthinkably vile detail drawn from the actual history of the Loudun case. The film’s most notorious sequence, removed from most surviving copies by the studio and censors, is the “Rape of Christ” sequence. In the two-minute sequence, naked, orgasmic nuns pull down a massive statue of Jesus and begin rubbing themselves on its face, hands, and groin. Another nun gratifies herself with a candle. The sight of undulating bodies in ecstasy prompts Father Mignon to begin feverishly masturbating. The whole sequence underscores the film’s theme of religious, sexual, and political hypocrisy in an unruly two minutes of screen time. And while it’s a shame the sequence was cut against the director’s wishes, Russell’s zoom-in-and-zoom-out technique, which suggests masturbation, proves to be a broad visual touch that The Devils may be better without.

Once Russell completed shooting the picture, the director faced a grueling process of showing The Devils to censors and reaching compromises over their suggested edits. Both John Trevelyan of the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) and Warner Bros. executives would eventually target the “Rape of Christ” sequence; Grandier’s torture and burning at the stake; scenes that involved sexuality and religion together; Redgrave’s use of the word “cunt;” and a scene where Sister Jeanne masturbates with Grandier’s charred femur. The long back-and-forth process between Russell and various censorship groups has been detailed in other writings and the made-for-TV documentary Hell on Earth: The Desecration and Resurrection of “The Devils” from 2002. But one gleans from these accounts that, no matter how much Russell removed, some members of the BBFC board could not clear enough to resolve their sense that The Devils was blasphemous. Many, including Trevelyan and BBFC president Lord Harlech, acknowledged that Russell’s film was not pornographic as some claimed, given the historical context and meaning behind the film, but not all examiners were so forgiving. It did not matter that the film was based on actual events; the material was deemed “way over the top,” according to BBFC censor Ken Perry. The excessive quality of Russell’s aesthetic felt like an attack to some censors, particularly in conservative America. The final UK version was cut to 111 minutes and received an X certificate (18 and older); in the United States, the censor cut even more, reducing the film to 108 minutes that were “incomprehensible,” according to Russell.

Before The Devils reached theaters, Warner Bros. distributed press kits warning publications that the film’s content limited the audience to “cinema groups” and “intellectual and artistic leaders of the community.” In other words, the studio knew that Russell’s film would never appeal to average moviegoers. Indeed, the film’s cocktail of religious imagery mixed with unhinged sexuality and disturbing violence unsettled most viewers and critics, and the film struggled at the box office as a result. And aside from the rare praise from critics such as Time magazine’s Jay Cocks—who called the film “unsparingly vivid in its imaginary” and “so totally successful in conveying an atmosphere of uncontrolled hysteria that Russell himself seems like a man possessed”—most major outlets published scathing reviews, including Variety, Newsweek, and The New Yorker. Roger Ebert gave the film zero stars in a dismissive review written entirely in a tone of sarcasm. Vincent Canby’s review in The New York Times called it “a movie less interested in coherent thought than in spectacle.” Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called it a “despicable piece of art.” Most notably, London Evening Standard critic Alexander Walker described the film as the “masturbatory fantasies of a Roman Catholic Schoolboy” and, curiously, seems to have imagined a scene depicting Reed’s penis getting crushed. Walker’s inaccurate review became a source of contention for Russell, who confronted the critic on the late-night news show Tonight. Russell called him out on his error, shouting, “You made it up, didn’t you?” The heated exchange ended with Russell storming off the TV set, but not before swatting Walker on his famously high-coiffed hair with a copy of the critic’s review.

Stranger still, two years later, William Friedkin’s adaptation of William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist arrived in theaters, and the resulting phenomenon was 1973’s top box-office grosser. Many have speculated why two films, both released by Warner Bros., both about exorcisms, both based on true stories (loosely in The Exorcist’s case), and both made by temperamental directors, earned two entirely different responses. Crouse notes that one reason may have been that the MPAA had changed and become more lenient; even its president, Jack Valenti, endorsed Friedkin’s film. And while The Exorcist featured a teenage girl stabbing her vagina with a crucifix and announcing, “Let Jesus fuck you,” the film never questioned the church’s authority or suggested that religious beliefs would be exploited for political power. Pauline Kael called the film “the biggest recruiting poster the Catholic Church has had.” Conversely, The Devils invites the viewer to question their faith, the integrity of religious institutions, and how the state can use the church as a political weapon. The Exorcist portrays clergy members as sympathetic, flawed, but never less than righteous in their mission; The Devils shows them as having agendas, abusing their power, and containing all the potential complications, dimensions, and perversions of any human being. Ultimately, The Exorcist reinforces religious faith and trust in the Catholic Church, while The Devils questions its leaders, shatters its icons, and reveals its hypocrisies.

Stranger still, two years later, William Friedkin’s adaptation of William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist arrived in theaters, and the resulting phenomenon was 1973’s top box-office grosser. Many have speculated why two films, both released by Warner Bros., both about exorcisms, both based on true stories (loosely in The Exorcist’s case), and both made by temperamental directors, earned two entirely different responses. Crouse notes that one reason may have been that the MPAA had changed and become more lenient; even its president, Jack Valenti, endorsed Friedkin’s film. And while The Exorcist featured a teenage girl stabbing her vagina with a crucifix and announcing, “Let Jesus fuck you,” the film never questioned the church’s authority or suggested that religious beliefs would be exploited for political power. Pauline Kael called the film “the biggest recruiting poster the Catholic Church has had.” Conversely, The Devils invites the viewer to question their faith, the integrity of religious institutions, and how the state can use the church as a political weapon. The Exorcist portrays clergy members as sympathetic, flawed, but never less than righteous in their mission; The Devils shows them as having agendas, abusing their power, and containing all the potential complications, dimensions, and perversions of any human being. Ultimately, The Exorcist reinforces religious faith and trust in the Catholic Church, while The Devils questions its leaders, shatters its icons, and reveals its hypocrisies.

Ironically, the commentary in Russell’s film about repression as a means of power became a reflection of what would happen to his film, just as the film’s witch-hunt theme anticipates the response from sensors, critics, and even the studio. Ever since, Warner Bros. has avoided putting The Devils on physical media or making it available to rent digitally in the United States, despite the occasional theatrical re-release in the 1970s and 1980s. In 2012, the British Film Institute released a DVD of the 111-minute cut, and digital versions of the 108-minute cut have appeared briefly on iTunes, The Criterion Channel, and Shudder, only to be quickly removed. Kermode has led a campaign to convince Warner Bros. not only to release the film in an accessible format but to restore the director’s cut, which includes the “Rape of Christ” sequence. Filmmakers such as Alex Cox, Joe Dante, and Guillermo del Toro have spoken out against Warner Bros.’s handling of the situation. What remains so curious about the case of The Devils and the studio’s reaction is that many other studios either distribute controversial films under another company or sell them. But Warner Bros. chose to keep their name attached to The Devils during the original release and, ever since, has ostensibly vaulted the film and prevented the public from seeing it. Even after Kermode went to great lengths to restore the complete director’s cut and arrange several UK screenings in 2004, all of which received high praise and standing ovations from the hundreds in attendance, Warner Bros. still refuses to allow any widespread distribution of The Devils in what must be the most shocking display of self-censorship ever from a major studio.

The legacy of Russell’s film almost threatens to outshine its substance as an expressive work of art, sometimes categorized as horror. Despite the historical origins, political underpinnings, and themes of corruption, power, and psychological manipulation, the director’s emphatic style feels like a nightmare. From a particular perspective—namely, this writer’s atheistic one—The Devils has much in common with works of folk horror, such as The Wicker Man (1973) or Midsommar (2019). In both examples, a central character becomes the victim of a localized religious fervor when he opposes the belief systems of those in power and is burned alive in service of a ritualistic doctrine or agenda. In each case, including The Devils, death becomes a method of sacrifice or setting the world straight, while the viewer registers the act as monstrous and backward—the work of dangerous zealots. More terrifying still is how the religious reasoning for Grandier’s death is merely a pretense for a political takeover. Even so, The Devils supplies such a radical experience within its concentration of aberrant sexual obsession, mounds of plague corpses, unthinkable torture, supposed demonic possessions, and bizarre exorcism rituals that it cannot help but feel like a horror film—albeit an alternate breed of religious horror rooted in critiquing the perverse Christian dogma outlined by the church’s ruling authority and the political forces that brandish them.

The Devils is an overwhelming film—an intelligent and never-understated examination of the holy and grotesque, a formally rich and varied work of art, and a behind-the-scenes story that ranks among the most compelling in film history. In a way, Russell acknowledged the vast reach of his film when he demonstrated to his composer that he couldn’t decide what his film was about. Davies remarked, “I remember him saying one day this film was a political one; the next day it was a religious film; the next day it was about persecution pure and simple.” Of course, the film is about all these things and more, including a statement about the enduring dangers of sexual repression, particularly as it relates to the state dictating acceptable sexual activity—an all-too-relative theme in the twenty-first century. In an experience best described as a sensory overload, Russell’s film can feel off-kilter yet intentional in its paradoxes, uneven yet thoughtful, classical but also bracingly original. It’s a wholly unconventional and visionary film whose cynicism and harshness deliver a blow to political and religious exploitation and abuses of power. Such lines describe much of Russell’s work as a director. “People are always saying my films are bizarre,” Russell told interviewer Thomas R. Atkins, “but they pale beside reality.” For all of Russell’s provocations in the form of blasphemy, possession, sex, hypocrisy, and corruption in plague times, the story of The Devils remains part of human history, and perhaps more reflective of humanity than most would care to admit.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on November 17, 2023.)

Bibliography:

Certeau, Michel de. The Possession at Loudun. Translated by Michael B. Smith. University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Crouse, Richard. Raising Hell: Ken Russell and the Unmaking of The Devils. Ecw Press, 2012.

Dempsey, Michael. “The World of Ken Russell.” Film Quarterly, vol. 25, no. 3, 1972, pp. 13–25. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1211517. Accessed 1 September 2022.

Ferber, Sarah. Demonic Possession and Exorcism in Early Modern France. Routledge, 2004.

Fisher, Jack. “Three Masterpieces of Sexuality: Women in Love, The Music Lovers, The Devils.” Ken Russell. Monarch Film Studies. Edited by Thomas R. Atkins. Monarch Press, 1976, pp. 39-68.

Flanagan, Kevin M., editor. Ken Russell: Re-Viewing England’s Last Mannerist. Scarecrow Press, 2009.

Gomez, Joseph A. Ken Russell: The Adaptor as Creator. Muller, 1976.

Huxley, Aldous. The Devils of Loudun. Harper and Brothers, 1952.

Joyce, Paul, director. Hell on Earth: The Desecration and Resurrection of “The Devils”. Film Four International, 2002.

Lanza, Joseph. Phallic Frenzy: Ken Russell and His Films. Chicago Review Press, 2007.

Russell, Ken. Altered States: The Autobiography of Ken Russell. Bantam Books, 1991.

Yacowar, Maurice. “Ken Russell’s Rabelais.” Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 8, no. 1, 1980, pp. 41–51. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43796127. Accessed 1 September 2022.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review