The Definitives

Moolaadé

Essay by Brian Eggert |

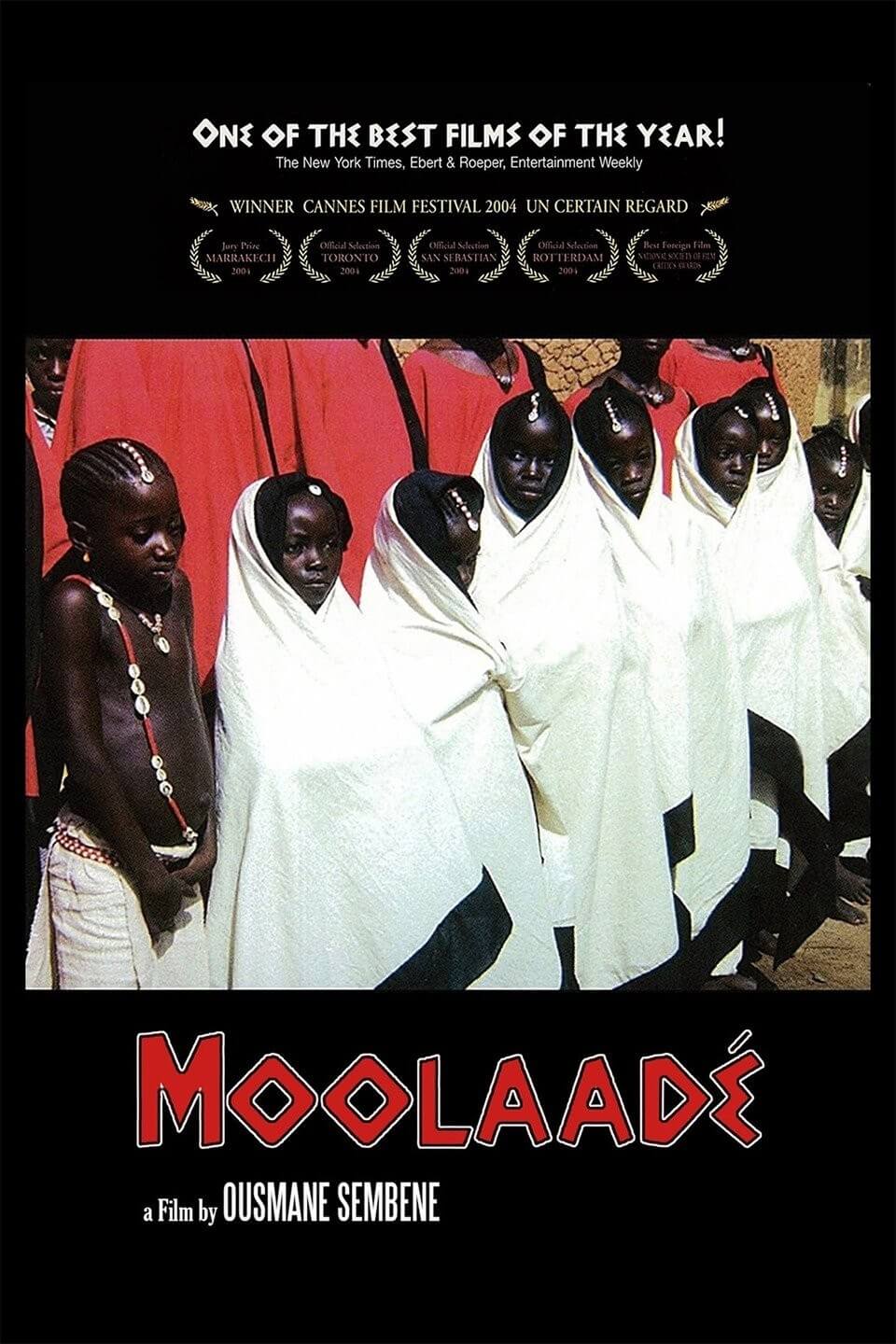

A beautiful, fleeting image occurs early in Moolaadé. In one of the film’s many brief observations of Nature, two goats play just outside the entrance to a village home. The buck tries to mount the female from behind, but she shakes off her suitor and, to escape, leaps over the multicolored rope that has been tied to pegs on either side of the exterior entryway. Rather than pursue the doe, the buck darts in the other direction, as if he knows there’s no crossing the rope for him. Indeed, the barrier is an invocation of the moolaadé, a sanctuary spell designed to bar anyone unwanted from passing over its line. The film’s heroine, named Collé, has placed the rope there to stop a band of ministerial village women, known as the Salindana, from carrying out their customary female circumcisions on four young girls under her protection. The traditional cutting, passed down through Islam, is jealously adhered to by the village’s patriarchal, polygamist leadership who nonetheless remain powerless against the will of Collé’s spell. The brief exchange between the goats might perfectly encapsulate the film’s theme of female comradeship against male-dominated rituals over their bodies, and yet it could have only been conjured by coincidence, one of those little miracles that remind us that making a film is about organizing chaos.

Moolaadé was the last film made by Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène, a legendary figure in sub-Saharan African cinema. Released in 2004, just three years before Sembène’s death, the film censures the procedure of female genital mutilation practiced in dozens of countries throughout Africa. Sembène outlines a dialectal conflict that never moralizes through speechifying or talking down to the viewer; he achieves his progressive arguments on both intellectual and emotional terms, allowing his story to connect with mass audiences not only throughout Africa but on a global scale. Sembène’s message in Moolaadé remains somewhat unique within his career, in that he normally focuses on African identity in terms of race, slavery, and colonization through didactic themes of anti-colonialism and cultural engagement. With a cast of relative unknowns, he raises the question of heritage within African identity, which is a subject often overlooked due to the destructive force of slavery and colonialism on African culture. Heritage, and its sometimes backward dependence on tradition, becomes central to the contemporary world in his film.

Moolaadé takes place in Djerisso, a Muslim village in Burkina Faso, a county in West Africa that shows faint signs of France’s colonial rule, most obviously the use of French by some of the villagers. Apart from the radios that provide the local women their favorite pastime, the conveniences remain few; the mud houses are painted pink, the people are dressed in luminescent colors and detailed patterns, and bright plastic containers are among their only modern possessions. Their isolation has fueled their reliance on traditions, leaving them unable to progress in matters of social justice or gender equality. Early in the film, when Collé (Fatoumata Coulibaly) invokes the moolaadé to protect the four girls from being cut, the village elders consider the matter “a minor domestic issue.” They presume it will be resolved when her husband, Ciré Bathiliy (Rasmane Ouedraogo), eventually orders Collé, his second and favorite of three wives, to utter the word that will lift the protection. But Collé refused to submit her daughter, Amasatou (Salimata Traoré), to the procedure, defying the will of the elders, and she will protect the four girls with the same passion. What is more, Ciré supported her choice concerning Amasatou. Evidently, Ciré is sympathetic to female identity, the pressures to control his wife notwithstanding.

Collé’s use of the moolaadé represents a challenge to the village’s patriarchal-tilted balance of power, in place for generations. The male-dominated culture finds women as subordinates, kneeling upon the arrival of the exclusively male village leaders, or even the male heads of the house. Following Islam, women rely on securing a husband for their livelihood, and the polygamist village puts the husband as the head of every household, with up to four wives beneath him. Given the isolation and concentration on traditionalism in Djerisso, the elders reinforce female genital mutilation in service of Islamic tradition—regardless of what Collé, Ciré’s eldest wife Hadjatou (Maimouna Hélène Diarra), and the other women have heard on their radios that, contrary to what the village elders say, Islam no longer requires the procedure. Moreover, by refusing to allow the girls to be cut, Collé makes a decision for her and the girls’ futures. Traditionalists in the village consider an uncircumcised woman—known as a bilakoro—unmarriable. “You will never get a husband,” they tell Amasatou. Collé understands that more hangs in the balance than finding a suitable partner. “It’s a matter of life and death,” she explains.

Although Sembène avoids the gristlier details of what the villagers call “excision” or more commonly “purification,” the dialogue and the few implied images around genital cutting are no less difficult. Female genital mutilation is dubbed FGM by the World Health Organization, which describes it as “procedures that intentionally alter or cause injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.” To be sure, the reasons behind genital cutting are not medical; they inhabit the realm of culture. Notions of social acceptance, marital worth, visual aesthetics, and male sexual pleasure result in the removal of the labia and clitoris for a narrowing of the vagina. But the scars from a Caesarean operation on Collé’s stomach tell another story, revealing how genital cutting can result in dangerous implications later in childbirth. Sembène shows us a screaming child being subjected to the process, the reality covered behind the Salindana priestess carrying out the procedure with, what is later shown later to be, a very old blade. He also shows us the consequences of FGM by intercutting between the Salindana priestesses “purifying” the young girl and Ciré on top of Collé, and Ciré’s violent thrusting, an apparent requisite with women who have undergone the procedure, leaves Collé weak and bleeding. Girls in the village heal from FGM under a gazebo, where the Salindana monitor them for weeks until their recovery—those who survive, anyway. Some of them cry from the need to pee, but they must resist passing urine in their current state. Removing the bandages could cause additional wounds and infection. In the village, the Salindana have incredible influence; they complain to the male elders about Collé, but her spell is stronger. The elders reply “no one can transgress the moolaadé.”

Although Sembène avoids the gristlier details of what the villagers call “excision” or more commonly “purification,” the dialogue and the few implied images around genital cutting are no less difficult. Female genital mutilation is dubbed FGM by the World Health Organization, which describes it as “procedures that intentionally alter or cause injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.” To be sure, the reasons behind genital cutting are not medical; they inhabit the realm of culture. Notions of social acceptance, marital worth, visual aesthetics, and male sexual pleasure result in the removal of the labia and clitoris for a narrowing of the vagina. But the scars from a Caesarean operation on Collé’s stomach tell another story, revealing how genital cutting can result in dangerous implications later in childbirth. Sembène shows us a screaming child being subjected to the process, the reality covered behind the Salindana priestess carrying out the procedure with, what is later shown later to be, a very old blade. He also shows us the consequences of FGM by intercutting between the Salindana priestesses “purifying” the young girl and Ciré on top of Collé, and Ciré’s violent thrusting, an apparent requisite with women who have undergone the procedure, leaves Collé weak and bleeding. Girls in the village heal from FGM under a gazebo, where the Salindana monitor them for weeks until their recovery—those who survive, anyway. Some of them cry from the need to pee, but they must resist passing urine in their current state. Removing the bandages could cause additional wounds and infection. In the village, the Salindana have incredible influence; they complain to the male elders about Collé, but her spell is stronger. The elders reply “no one can transgress the moolaadé.”

Sembène explores traditionalism beyond the cutting procedure. A subplot follows the arranged marriage of Amasatou, who has been promised to Doucouré Ibrahima (Théophile Sowié), the “handsome as the rising sun” heir to the village throne who has just returned from France. Amasatou nervously prepares for her wedding day, taking out credit with the traveling vendor Mercenaire (Dominique Zeïda)—a womanizer who’s not above propositioning women to pay for goods with sex—and comes home with bundles of expensive items for the ceremony. Thinking of her future, Amasatou urges her mother to allow the “purification” to take place. But Collé has determined Amasatou will remain a bilakoro, a choice that renders her an unsuitable mate according to Doucouré’s father, the village chief. With Amasatou unfit, Doucouré’s father arranges for him to marry Fily, his 11-year old cousin. Doucouré refuses, telling his father that his marriage is his business, a reaction that incites the chief to threaten Doucouré with disinheritance. Even men from other areas find Djerisso’s practices outdated. Mercenaire, formerly an officer for the United Nations before being scapegoated, accuses Doucouré, his father, and other men in the village of pedophilia for their willingness to arrange a marriage with an 11-year-old girl.

The conflict in the village comes to a head when two young girls, who are not under Collé’s protection but escaped the Salindana, resolve to throw themselves into a well rather than acquiesce to cutting. The village is shaken. The men determine that radios have influenced the minds of their women and resolve to confiscate every radio in the village. The women, already outraged by the death of the girls, find their single vice confiscated. Although few of the women in the village support the “purification” process, their radios demarcate a clear division in the village: men versus women. Trying to re-establish male dominance, Ciré’s elder brother Amath (Ousmane Konaté) orders him to “regain authority” by flogging his wife and demanding that she break the moolaadé enchantment. The public beating proceeds with an unruly crowd shouting “Tame her!” as Ciré demands “Say it!” with tears filling his eyes. Amath has forced Ciré’s hand, after all. Still, Collé refuses to break the spell. The gristly scene comes to an end when Mercenaire interrupts the beating, a moment of bravery in the face of barbarism that earns his banishment and ultimately murder by a band of torch-wielding villagers.

Scholar S.O. Opondo notes that, by giving them agency, Sembène forces the audience to rethink stereotypes of African women as mere victims of their patriarchal cultures that leave them robbed of human rights. Moolaadé shows women coming together, taking a stand against the patriarchs, the oppressive traditions, and asserting control. Certainly, Collé’s flogging leads to the undoing of the village elders. The act engenders sympathy for Collé’s cause among the village women, while also forcing Ciré to rethink where his loyalties lie. Far more tragic, during Collé’s public beating, one of the girls she was protecting was coaxed out from behind the moolaadé rope. The girl was cut and bled to death. The other three mothers are reunited with their children, while the mother of the dead girl wails in sorrow. Meanwhile, the elders collect and pile all of the village’s radios in the square, and then set them ablaze, an act that cannot help but recall a Nazi book burning. At this, the women of Djerisso unite, with machetes in hand, and force the Salindana to throw down their rusty circumcision knives, which are tossed into the fire. “No girl will ever get cut again!” they announce. The final moments are a celebration as the village women declare their joyous victory. “Wassa wassa!”

Scholar S.O. Opondo notes that, by giving them agency, Sembène forces the audience to rethink stereotypes of African women as mere victims of their patriarchal cultures that leave them robbed of human rights. Moolaadé shows women coming together, taking a stand against the patriarchs, the oppressive traditions, and asserting control. Certainly, Collé’s flogging leads to the undoing of the village elders. The act engenders sympathy for Collé’s cause among the village women, while also forcing Ciré to rethink where his loyalties lie. Far more tragic, during Collé’s public beating, one of the girls she was protecting was coaxed out from behind the moolaadé rope. The girl was cut and bled to death. The other three mothers are reunited with their children, while the mother of the dead girl wails in sorrow. Meanwhile, the elders collect and pile all of the village’s radios in the square, and then set them ablaze, an act that cannot help but recall a Nazi book burning. At this, the women of Djerisso unite, with machetes in hand, and force the Salindana to throw down their rusty circumcision knives, which are tossed into the fire. “No girl will ever get cut again!” they announce. The final moments are a celebration as the village women declare their joyous victory. “Wassa wassa!”

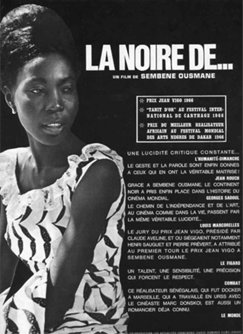

Sembène, who studied film in Moscow with Sergei Gerasimov and Mark Donskoi in the early 1960s, had come a long way since his debut, La noire de… (1966), a picture influenced by the Soviet and French New Wave styles. This is not to suggest that his filmmaking had developed into a more complex formal style. While his debut employed narrative and thematic metaphors through editing and voiceover, representing an unmatchable height in his career, Sembène and his cinematographer Dominique Gentil present a comparatively straightforward visual approach in Moolaadé. The camera often adopts a stationary image, with characters moving in and out of the frame. The matter-of-factness of his approach confronts the viewer with the story’s emotions, bringing the director’s commentaries to the forefront. Yet, their didacticism never devolves into pontification. Elsewhere, Sembène’s simple presentation allows room for something completely different: a nightmarish dream sequence in which the children see the Salindana, draped in their evocative crimson robes, as masked demons approaching from a black, foggy abyss.

Given his roots in Soviet film theory, Sembène viewed cinema as a medium of political communication, but he never resorts to propaganda. His films dramatize the human struggle to survive, achieve equality, and embrace human dignity, often in the face of colonial imperialism, even if those strains run contrary to African traditions. He is unafraid to criticize blind adherence to time-honored practices. As Rear Admiral Grace Hopper, a female computer programmer and U.S. Naval officer, famously said, “The most dangerous phrase in the language is, ‘We’ve always done it this way.'” This seems to be the guiding principle of Moolaadé, the first film that openly questioned FGM and, after its win of the Prize Un Certain Regard at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival, began a global dialogue on the subject. Collé questions the male authority over women’s bodies, challenging the traditional and violent removal of female identity and agency, both in psychological and physical terms, that occurs through the purification ritual.

On the surface, Moolaadé may seem to be a film solely concerned with the social conditions and subjectivity of women in certain African cultures. But as referenced above, Sembène films often contain a suspicion and harsh critical attitude towards colonization. This is evidenced in scenes built around Doucouré, who has returned from France a rich man, and what’s more with knowledge of the capitalistic world. “He must have brought back all the wealth of France,” says one villager, observing Doucouré’s pickup truck full of electronics and suitcases full of gifts for the village. Another villager says to his boy, “You too will go to France where the money is printed.” Since La noire de…, Sembène has weighed the remnants of French cultural colonialism after Senegal’s independence, largely in terms of African identity before and after France. Moolaadé suggests there is more than pre- and post-colonialism. By correcting political and social structures that existed in both African tradition and French colonialism, people like Collé can create something new.

Sembène makes no absolute denunciations about traditionalism, nor does he blindingly embrace modernism. As a humanist Marxist, he raises an eyebrow to capitalism; however, Moolaadé finds the director curiously embracing the knowledge imparted by media devices such as radio and television. All that is old is not evil; all that is new is not corrupted. For example, Collé’s progressive challenge to the patriarchy would not have been possible without the power the moolaadé, a spell that originated in the pre-Islamic traditions of magic in this region of Africa—mysticisms that, despite the adoption of an alternative religion, remain embedded into the culture’s ancient belief system. But traditions also perpetuated the film’s conflict. It is the village’s chief who demands order and blames radio and television for convincing the village’s women to go against the excision rite. Doucouré defends such media, declaring, “We cannot cut ourselves off from the progress of the world.” And in the film’s final shots, Sembène switches from the egglike top of the village mosque to a television antenna. Perhaps, through the juxtaposition of the two images, he demands the same level of criticism for media devices as religions. In either mode of communication, the ideology passed along remains something to be questioned and considered in its influence on humanity.

Moolaadé is a film about preserving the wholeness of identity for individuals as well as cultures. In a sense, every Sembène film yearns for a similar wholeness through his commentaries on postcolonial subjectivity, slavery, and racism. Collé grants the girls asylum through her spell, ensuring their whole identity and the future of Djerisso—two unsustainable identities that could not continue without a consistent injection of new life, which would be impossible when girls’ genitals have been mutilated, making births either difficult or deadly. Beyond the physical consequences, wholeness is an acceptance of progressive ideas, no matter how dubious their country of origin. Although France remained a target for much of the director’s career, their media product at least speaks to the fair treatment of women’s bodies. And so, Sembène’s film contains a testament to modernity and even seems to proclaim, “Watch and learn from television!” How unlikely a message from an otherwise rebellious, political filmmaker.

Moolaadé is a film about preserving the wholeness of identity for individuals as well as cultures. In a sense, every Sembène film yearns for a similar wholeness through his commentaries on postcolonial subjectivity, slavery, and racism. Collé grants the girls asylum through her spell, ensuring their whole identity and the future of Djerisso—two unsustainable identities that could not continue without a consistent injection of new life, which would be impossible when girls’ genitals have been mutilated, making births either difficult or deadly. Beyond the physical consequences, wholeness is an acceptance of progressive ideas, no matter how dubious their country of origin. Although France remained a target for much of the director’s career, their media product at least speaks to the fair treatment of women’s bodies. And so, Sembène’s film contains a testament to modernity and even seems to proclaim, “Watch and learn from television!” How unlikely a message from an otherwise rebellious, political filmmaker.

Ousmane Sembène made just nine feature films in forty years: La noire de…, Mandabi (1968), Emitai (1971), Xala (1974), Ceddo (1976), Camp de Thiaroye (1989), Guel-waar (1992), Faat Kine (2000), and Moolaadé. His films were about traditions and progress, nationalism and colonialism, patriarchies and humanism, identity and subjectivity, and ultimately the most transcendent conflict of them all: right and wrong. Few filmmakers from any country have assembled a body of work that maintained such a consistent vision, clarity of purpose, aesthetic confidence, and radicalism. With his final picture, he reminds the oppressed and dehumanized women throughout countries that practice FGM that hope gives birth to courage. His global reach as an internationally renown figure in political filmmaking ensured that his message was heard around the world. With rich cultural texture and profound emotions, Moolaadé is a tale of impassioned defiance and a celebration of female solidarity.

Bibliography:

Akin, Adesokan. “The Significance of Ousmane Sembène.” World Literature Today, no. 1, 2008, p. 37-39.

Diawara, Manthia. African Cinema: Politics and Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992.

Gadjigo, Samba. Ousmane Sembène: The Making of a Militant Artist. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

Matereke, Kudzai. “Rethinking Receptivity in a Postcolonial Context: Recasting Sembène’s Moolaade.” Ethics & Global Politics, vol. 5, no. 3, July 2012, pp. 153-170.

Opondo, S.O. “Cinema Is Our ‘Night School’: Appropriation, Falsification, and Dissensus in the Art of Ousmane Sembène.” African Identities, vol. 13, no. 1, 02 Jan. 2015, p. 34-48.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review