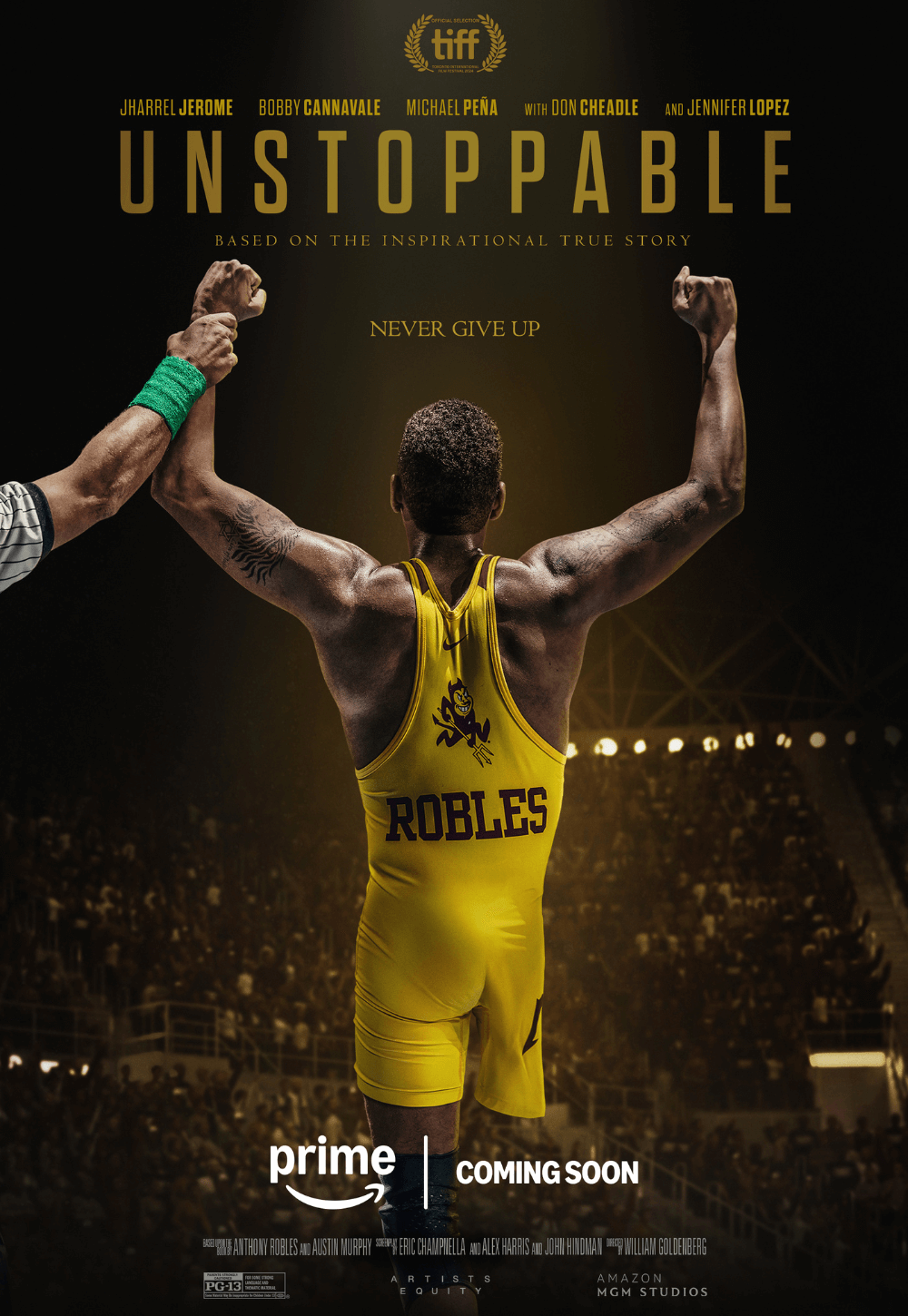

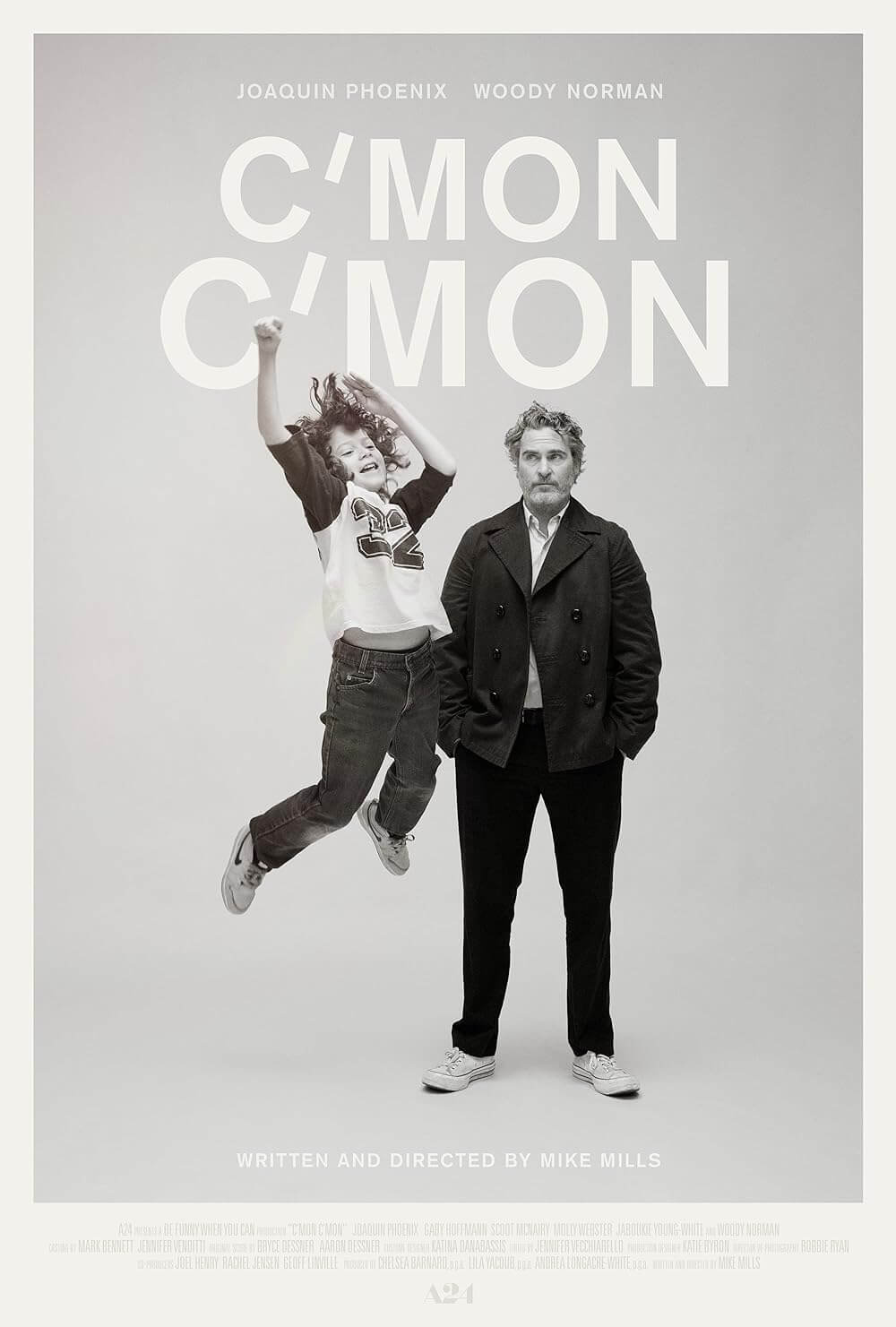

C’mon C’mon

Review by Brian Eggert | December 8, 2021

Mike Mills’ C’mon C’mon is a remarkable achievement. It’s one of those rare films that, despite its specific subject matter, feels like it’s about everything. Joaquin Phoenix plays Johnny, a radio journalist working on a project that entails interviewing children about their worldview and vision of the future. While Johnny’s estranged sister Viv (Gaby Hoffman) tries to get a handle on her husband Paul’s (Scoot McNairy) mental-health crisis, she entrusts her nine-year-old son Jesse (Woody Norman), a strange and idiosyncratic boy, to Johnny for a couple of weeks. Together, uncle and nephew travel from Los Angeles to New York to New Orleans on Johnny’s assignments, bonding along the way. What unfolds is a film about seeing beyond your bubble; about people trying to understand one another; about how children are more open to the world and different perspectives, and how adults gradually close themselves off; about how children will inherit an Earth that’s in worse condition than adults found it; about people figuring out how to take care of each other; about learning to listen; about planning for the future only to realize that nothing works out the way one wants it to; about embracing the uncertainty of parenthood, childhood, and life as a whole; and about the things people say, write, or create that help us understand the world a little better.

The setup follows Johnny, who’s single after a long and meaningful relationship ends, when he takes on the responsibility of looking after his nephew, initially in his sister’s house. It’s the first time he and Viv have talked since their mother died a year ago. Jesse hasn’t seen Johnny for a year either, which in kid time means an eternity. Beyond precocious, Jesse wakes Johnny up with some morning opera blaring. “I get to be loud on Saturday,” he explains. And over the coming days, Johnny and Viv keep in touch via phone and text. Of course, she misses her son, but she also gives Johnny, who’s unprepared for children, advice on managing Jesse. Regardless of the occasional misstep in his technique, Johnny finds himself identifying with Jesse, learning that the boy, like one of his interview subjects, has layer upon layer to his personality—and not every layer is easy to handle. When Johnny finds himself at wit’s end, Viv tells him, “Nobody knows what they’re doing with these kids. You just have to keep doing it.” But during their conversations, Johnny and Viv also untangle their hangups—Johnny’s interference in her marriage and their falling out over how to handle their mother’s decline.

A cynical viewer might dismiss this sort of thing as cloying or overly sentimental. But Mills does more than present a straightforward story involving family ties; he also explores an artistic process by including actual interviews with Johnny’s subjects, who ruminate on the world and place the film’s events into perspective. The real-life children who appear onscreen share their thoughts, and Johnny does something rare by simply listening and engaging in their perspectives—something adults rarely do. The disorganized Johnny, kept on task by his assistant Roxanne (Radiolab journalist Molly Webster), listens to the conversations and processes them in solitude later. We never see or hear a finished product in C’mon C’mon, but the work informs a theme about the power of capturing life on audio or video—echoed when Johnny reads from an essay by Cameraperson (2016) director Kristen Johnson about how recording someone immortalizes them. Jesse, who refuses to be interviewed, learns about Johnny’s process and finds himself interested in the audio equipment, using the headphones and mic to experience the world through a sense heightened by technology. For instance, by experiencing the world through a focus on sound, one better appreciates the place of sound in everyday life.

A cynical viewer might dismiss this sort of thing as cloying or overly sentimental. But Mills does more than present a straightforward story involving family ties; he also explores an artistic process by including actual interviews with Johnny’s subjects, who ruminate on the world and place the film’s events into perspective. The real-life children who appear onscreen share their thoughts, and Johnny does something rare by simply listening and engaging in their perspectives—something adults rarely do. The disorganized Johnny, kept on task by his assistant Roxanne (Radiolab journalist Molly Webster), listens to the conversations and processes them in solitude later. We never see or hear a finished product in C’mon C’mon, but the work informs a theme about the power of capturing life on audio or video—echoed when Johnny reads from an essay by Cameraperson (2016) director Kristen Johnson about how recording someone immortalizes them. Jesse, who refuses to be interviewed, learns about Johnny’s process and finds himself interested in the audio equipment, using the headphones and mic to experience the world through a sense heightened by technology. For instance, by experiencing the world through a focus on sound, one better appreciates the place of sound in everyday life.

C’mon C’mon feels like an art project that uses elements of narrative, documentary, rhapsodic montages, and readings from cherished literature and essays. Mills shoots in pristine black-and-white captured by cinematographer Robbie Ryan, which turns the film from an indie darling into compassionate photography like that of Diane Arbus. It draws out the humanity in everyday subjects, immortalizing them in monochrome, which oddly makes them feel more realistic. When Johnny and Jesse wrestle, laugh, argue, and grow frustrated with one another, the lack of color makes their scenes together feel like portraiture. Mills and editor Jennifer Vecchiarello structure the film in an impressionistic assemblage that follows a forward-moving narrative but includes all the supplementary influences (books, poems, essays) buzzing around in Johnny’s head. When he reads aloud excerpts from the essay Mothers by Jacqueline Rose or Star Child, the existential children’s book by Claire A. Nivola, Vecchiarello underscores the words with glorious montages of the characters inhabiting their spaces. The montage effect feels aching and affectionate in ways that bring words like poignant and transportive to mind.

The film is only the fourth feature by Mills, whose career consists of deeply personal, generally life-affirming indie projects. After years of designing album covers and directing short films, commercials, and music videos, Mills made his feature debut with Thumbsucker (2005), an adaptation of Walter Kim’s novel about a teen with arrested development. From there, Mills went on to make two films about his parents. Beginners (2010) was about his father, who came out as gay not long after his mother’s death, and earned the late Christopher Plummer an Oscar. His best film, 20th Century Women (2016), supplied a heartfelt ode to his mother and other women in his life through an almost kaleidoscopic array of powerful visuals and truthful observations. In each of his films, Mills shares a piece of himself and captures a life fully lived through a dizzying collage of history and future. His films are unique because they introduce people we feel we know and have shared a life with—after just two hours of being with them. Watching C’mon C’mon, it isn’t easy to tell whether the film is Mills’ most intimate or ambitious project yet. Somehow, it feels like both.

As ever, Mills had a lot on his mind. His film explores the strange phenomenon of how we start as children, but somewhere between then and adulthood, we forget what our minds used to be like—the attention we craved, the curiosity we had, the randomness of our thoughts and learning processes. More than once, Johnny experiences that dreaded moment every parent faces: Jesse goes missing. Johnny panics and, after finding Jesse and discovering it was either a joke or a test, he loses his temper. On one of his calls to Viv, Johnny remarks, “I guess you’re just used to it.” Viv replies, “I’m not used to it.” She confesses that despite her boundless love, at times, “I can barely stand to be in the same room with him going on and on, talking relentlessly about nothing, interrupting every thought I might have.” As an adult, it’s easy to forget how when we were children, we tested adults. And isn’t it strange how Jesse may not remember how he behaved as a child, but Johnny will?

As ever, Mills had a lot on his mind. His film explores the strange phenomenon of how we start as children, but somewhere between then and adulthood, we forget what our minds used to be like—the attention we craved, the curiosity we had, the randomness of our thoughts and learning processes. More than once, Johnny experiences that dreaded moment every parent faces: Jesse goes missing. Johnny panics and, after finding Jesse and discovering it was either a joke or a test, he loses his temper. On one of his calls to Viv, Johnny remarks, “I guess you’re just used to it.” Viv replies, “I’m not used to it.” She confesses that despite her boundless love, at times, “I can barely stand to be in the same room with him going on and on, talking relentlessly about nothing, interrupting every thought I might have.” As an adult, it’s easy to forget how when we were children, we tested adults. And isn’t it strange how Jesse may not remember how he behaved as a child, but Johnny will?

C’mon C’mon was inspired by Mills’ relationship with his child. Drawing from specific, personal experiences, Mills creates a lived-in atmosphere similar to his other films based on his family relationships. Not one moment feels artificial or untrue; these people seem to have known each other forever. Phoenix and Hoffman never hint that they’re acting, just caught up in their characters’ lives. It’s a full embodiment and display of naturalism on their parts, and especially subtle work for Phoenix, who’s known for his showy transformations in The Master (2012) and Joker (2019). Norman, too, has the presence of a child who Mills allowed to be himself. It’s not a child actor’s performance so much as Mills creating a space for Norman to behave like a kid—and more than that, a kid with some idiosyncratic impulses. Take the game Jesse plays where he pretends to be an orphan visiting from a foster home. Viv and Johnny both think the routine is weird and, even while wondering about its origins, play along to let Jesse work through whatever needs working through.

Mills shares several truisms and ponderings throughout the film. If some seem like obvious life lessons and far from revelatory, then perhaps Johnny represents how we can grow complacent or narrow-minded on our journey through life. We forget the things that matter, the life lessons we already learned, because we’re so driven to keep moving. Thank goodness for photography and audio recordings; they capture and preserve the moments that our memories will soon replace with something that, in retrospect, may prove insignificant by comparison. By returning to these documents and works of art, we can remember who we once were and aspired to become. C’mon C’mon circulates a lot of lofty subject matter but avoids feeling preachy or didactic by situating the viewer among human relationships that resonate and feel like real-life captured on film—in all the uncertainty, vulnerability, and sincerity that a childlike perspective affords. This is a special film, and though the story may sound familiar, Mills’ treatment makes for another of his unforgettable and affecting works of art.

Support Deep Focus Review

Help keep independent film criticism alive by supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon. Since 2007, I’ve aimed to deliver critical analysis and in-depth reviews, free from outside influence. Your contribution not only gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, but it also helps me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong. If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways. Thank you for your readership!