The Definitives

Critical essays, histories, and appreciations of great films

La noire de…

- Director

- Ousmane Sembène

- Cast

- M’Bissine Thérèse Diop, Anne-Marie Jelinek, Robert Fontaine, Momar Nar Sene, Toto Bissainthe

- Rated

- Unrated

- Runtime

- 59 min.

- Release Date

- 12/31/1966

Ousmane Sembène wrote and directed La noire de…, a rebellious Senegalese film in which he exposes the postcolonial scars left by France after their settlement of his country. Although other films had been made in Africa upon its release in 1966, Sembène made the first feature directed by a sub-Saharan African, the first to receive global recognition, and what is often considered Africa’s first independent feature. Through the harrowing story of Diouana, a young woman from Dakar, Senegal, who accepts a nanny position with a French bourgeois family in Antibes, France, the film dissects the neocolonial relationship between the former colonizer and colonized. Based on a short story Sembène published as part of a volume of short stories in 1962, titled Voltaïque, La noire de… slices into France’s neocolonialist grip on Senegal’s economic and cultural identities. Sembène’s struggle to get the film made and his eventual formal techniques further reveal a dual identity that has been shaped by French influences, suggesting that any manner of postcolonial identity has been fractured into an unrecoverable multiplicity. Above all, Sembène provides a brilliant and devastating allegory for the postcolonial subjectivity of its main character, himself, and the cultural identity of Senegal.

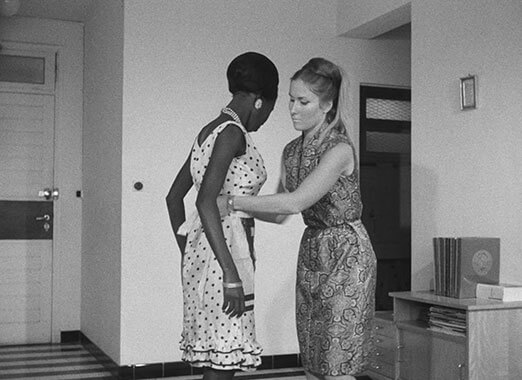

The film opens as Diouana, played by untrained actress M’Bissine Thérèse Diop, arrives in the French Riviera from her home in Dakar. She was hired as a nanny and, in Dakar, took care of three children belonging to her employers, a French couple known only as Monsieur (Robert Fontaine) and Madame (Anne-Marie Jelinek). When she arrives in Antibes, Diouana discovers the Madame expects her to serve as a cook, maid, and laundress. The children are nowhere to be found. What’s more, the Madame’s mannerisms have shifted for the worse. Now in France, she is hostile and demanding. She constantly gives orders to Diouana and insists that she wear an apron to look the part of a servant. The Monsieur, meanwhile, is disaffected and aloof, oblivious not only to Diouanna’s growing disenchantment but any conflict in their apartment. Shortly after returning to Antibes, the couple has a lunch party to show off their new African servant to their bourgeois friends. The Madame orders Diouana to cook rice and peanut sauce, suggesting “Africans only eat rice” to her guests. Diouana wonders why she was asked to make rice, as the Madame never ate rice in Dakar. While Diouana serves a meal that evidently designed to characterize her people as poor and simple, one of the French men at the table gazes at Diouana and notes, “I’ve never kissed a black woman.” He then proceeds to deliver an unwelcomed kiss, to which Diouana does not respond.

Diouana’s subjectivity becomes undeniable. Consumed with depression over her situation, she falls into her memories of how, back in Dakar, she was once hopeful about her trip to France. Through Diouana’s internal monologue (voiced by Toto Bissainthe, as Diop never actually speaks in the film), we learn that in Dakar she had a boyfriend and mother, but no job. Eventually, she was hired by the Madame, who was sure to ask, “Have you ever worked for white people before?” When she was first hired, Diouana gave the French family a mask. For them, it is a symbol of Africa and one in a number of masks they have collected, and it hangs on their wall in Antibes. When the Madame asked Diouana to join them in Antibes, the promise of France’s cosmopolitan scene—with its shops, fashion, and glamor—were alluring. But now that she’s in France, Diouana never leaves the couple’s apartment. She has too much work, and the French couple has not introduced her to the local culture. She remains inside, her world confined within the white walls of the small living space.

Diouana’s subjectivity becomes undeniable. Consumed with depression over her situation, she falls into her memories of how, back in Dakar, she was once hopeful about her trip to France. Through Diouana’s internal monologue (voiced by Toto Bissainthe, as Diop never actually speaks in the film), we learn that in Dakar she had a boyfriend and mother, but no job. Eventually, she was hired by the Madame, who was sure to ask, “Have you ever worked for white people before?” When she was first hired, Diouana gave the French family a mask. For them, it is a symbol of Africa and one in a number of masks they have collected, and it hangs on their wall in Antibes. When the Madame asked Diouana to join them in Antibes, the promise of France’s cosmopolitan scene—with its shops, fashion, and glamor—were alluring. But now that she’s in France, Diouana never leaves the couple’s apartment. She has too much work, and the French couple has not introduced her to the local culture. She remains inside, her world confined within the white walls of the small living space.

Reflecting on her confinement in the apartment, Diouana wonders to herself, “Is this what it means to live in France?” Inconsolable over her situation, Diouana’s melancholy consumes her. She cannot work or get out of bed. When her mother writes to the French couple’s apartment, Diouana cannot reply. The Monsieur determines to write back for her, occupying Diouanna’s voice, but she refuses and tears up the letter. The Madame, ever hostile and intolerant, threatens not to feed Diouana unless she works, and Diouana refuses to work unless she’s fed. Diouana realizes, “I’m their prisoner… their slave.” She resolves, “Never again.” She will not be their slave or caretaker. She will not listen to the Madame’s orders or even look at them again. No one will own her. No one will fragment her. And so, Diouana packs her things, goes into the bathroom, and then slits her throat in the bathtub. In the aftermath, the Monsieur returns to Dakar with Diouana’s things, her back pay, and mask, hoping her mother will accept them. Diouana’s mother refuses the money. But a young boy takes the mask, covers his face, and follows the Monsieur through the Dakar village, as though Diouana’s specter was haunting him.

To understand the consequence of La noire de…, the relationship between Senegal and France must be historicized. Much of Africa, Senegal included, was colonized by Europe over several centuries. The French built their first factory and trading station on the Senegal River in 1638, establishing an industry dependent on slaves, gold, peanuts, and gum. Over hundreds of years, the French clashed with their British rivals over trade routes in Africa before France’s Second Republic outlawed slavery on French soil in 1848 and subsequently took power in Senegal in 1895. The autocratic French Empire, controlling many countries in West Africa, considered members of its colonies to be French citizens, which also meant they used these populations to recruit hundreds of thousands of soldiers for the First and Second World Wars. Following the massive death toll of Senegalese in WWII, nationalist movements in Senegal gradually vied for independence from their French colonists after 1946. Senegal became independent of France in 1960, but Charles de Gaulle’s administration created the Ministry of Cooperation to continue to shape former colonies through an institutionalized support system to “maintain the colonial legacy of assimilation, perpetuating and strengthening a Franco-African cultural connection” in all areas of culture. The policy of French assimilation remained more prevalent in Senegal than in any of their other African colonies; therefore, Senegal served as a figurehead for how the rest of colonized Africa would react to their decolonization.

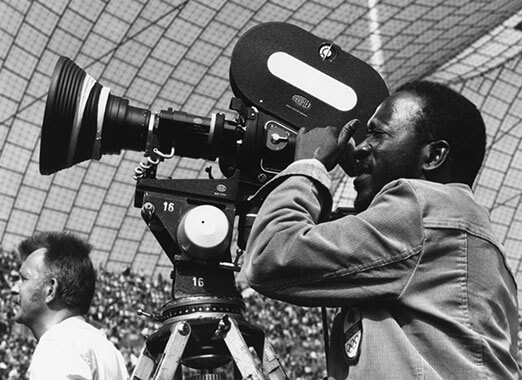

Sembène came to film much later in life than most filmmakers. He grew up in Casamance, Senegal, before moving to the capital city, Dakar, as a teenager. In 1944, Sembène was drafted into WWII to fight for France, believing it was his duty to protect the French “fatherland.” However, he began to question his colonialized identity after Allied bombers killed hundreds in Dakar while fighting against Vichy France and its colonies. In the 1940s, he experienced racism for the first time in his life that he could remember, and such confrontations made him realize that he and other Senegalese were disposable to the French. He was a colonial subject. After the war, Sembène went to Marseille and studied, served as a dock worker, and became a militant unionist after studying Marxism at the General Confederation of Labor and the French Community Party libraries. He learned about and followed a humanist Marxist ideology, but he quickly realized that political theory was not enough; to create change within the human “cultural animal,” he would have to influence culture through art. This realization would eventually shape how he made films enriched by political and cultural perspectives.

Sembène came to film much later in life than most filmmakers. He grew up in Casamance, Senegal, before moving to the capital city, Dakar, as a teenager. In 1944, Sembène was drafted into WWII to fight for France, believing it was his duty to protect the French “fatherland.” However, he began to question his colonialized identity after Allied bombers killed hundreds in Dakar while fighting against Vichy France and its colonies. In the 1940s, he experienced racism for the first time in his life that he could remember, and such confrontations made him realize that he and other Senegalese were disposable to the French. He was a colonial subject. After the war, Sembène went to Marseille and studied, served as a dock worker, and became a militant unionist after studying Marxism at the General Confederation of Labor and the French Community Party libraries. He learned about and followed a humanist Marxist ideology, but he quickly realized that political theory was not enough; to create change within the human “cultural animal,” he would have to influence culture through art. This realization would eventually shape how he made films enriched by political and cultural perspectives.

He returned to Dakar in 1947, when he participated in the Dakar-Niger railway strike in which the African railwaymen demanded the same rights as the Frenchmen. He eventually wrote his first novel, Le Docker noir, published in 1956, based on his experiences in Marseille. He also wrote about the railway strike in his 1960 book, Les bouts de bois de Dieu (God’s Bits of Wood). Focused on literature, he published ten novels, but he soon realized that language, with its myriad of potential translations and rampant illiteracy, was a limiting factor in the number of people he could reach. At 40, he went to film school and learned filmmaking, hoping the new medium would allow him to reach a wider audience. La noire de… was his first major release, and he followed it with Mandabi (1968), the first film made in the African language Wolof; he later made films in the languages of Joola and Jula. Throughout his career, he helped launch the Carthage International Film Festival and the First World Festival of Negro Arts, held in 1966, bringing global attention to African filmmakers. Until his death in 2007, he told stories not just about race but about marginalized people whose lives are overlooked by the international media—such as Moolaadé (2004), about the practice of female genital mutilation in some African countries.

When Sembène first set out to make La noire de…, he soon realized that even the Senegalese film industry had been colonized. France, having a lively cinematic tradition, fostered the film industry for Senegal through the Ministry of Cooperation, establishing production institutions such as the Bureau du Cinéma and Centre national du cinema (CNC). These institutions taught the Senegalese how to make films and thus create their own cinema; however, they also integrated the cultural and artistic trends of French filmmakers—though the political colonization had ended, the cultural colonization survived. Filmmakers from any of France’s former colonies could have their films fully produced and financed by the Bureau du Cinéma, provided a localized (but French National) committee in Senegal approved the script before filming began. Another option: African filmmakers could make their films independently and submit them to the Bureau du Cinéma, which would, in turn, offer to reimburse the filmmaker the cost of production in exchange for its distribution rights. This means the former colonizer could own the cultural product of its former colony and profit from it. Furthermore, finding distribution in one of Senegal’s seventy movie theaters, each filled with the cultural production from the French and Hollywood, proved all but impossible for an African filmmaker. In the coming decades, Sembène would find it easier to get his films shown in Paris than in any African city.

The only instance of the Bureau du Cinéma denying any proposed film at the time was La noire de…, probably because the central French characters, the cruel Madame and feeble Monsieur, are each employed by the Ministry of Cooperation. Sembène’s film was a collaborative co-production between his production unit Domirev and Les Actualités Françaises, and he began shooting without the necessary permission of the Bureau du Cinéma. Although he worked with Les Actualités Françaises to get the film made, the bureaucracy of the Bureau du Cinéma and CNC required him to have a “professional card”—which could only be acquired by making a film or serving as an assistant on a film. Additionally, France’s oversight committee in Senegal made it difficult for first-time filmmakers to get their films made. And so, Sembène struggled to get a “professional card” and secure financing to complete his original vision. Because Sembène never received the correct authorization, the film, which was originally supposed to be a 90-minute feature, was cut short to qualify La noire de… as a longer-than-usual short film. The shorter length (59 minutes) allowed Sembène to circumvent some of the bureaucracy associated with the Bureau du Cinéma and CNC’s policies. Regardless, Sembène considered the film a short feature film. As scholar Steven Malčić observed, “These institutions forced Sembène to experience spatiotemporal displacement, requiring him to be both French and Senegalese, both colonized and living in a postcolonial Dakar.” The extent to which Sembène was forced to work in and financially depend on France’s bureaucratic system of production, despite being a citizen of independent Senegal, strangely mirrors Diouana’s economic dependence on her employers.

The only instance of the Bureau du Cinéma denying any proposed film at the time was La noire de…, probably because the central French characters, the cruel Madame and feeble Monsieur, are each employed by the Ministry of Cooperation. Sembène’s film was a collaborative co-production between his production unit Domirev and Les Actualités Françaises, and he began shooting without the necessary permission of the Bureau du Cinéma. Although he worked with Les Actualités Françaises to get the film made, the bureaucracy of the Bureau du Cinéma and CNC required him to have a “professional card”—which could only be acquired by making a film or serving as an assistant on a film. Additionally, France’s oversight committee in Senegal made it difficult for first-time filmmakers to get their films made. And so, Sembène struggled to get a “professional card” and secure financing to complete his original vision. Because Sembène never received the correct authorization, the film, which was originally supposed to be a 90-minute feature, was cut short to qualify La noire de… as a longer-than-usual short film. The shorter length (59 minutes) allowed Sembène to circumvent some of the bureaucracy associated with the Bureau du Cinéma and CNC’s policies. Regardless, Sembène considered the film a short feature film. As scholar Steven Malčić observed, “These institutions forced Sembène to experience spatiotemporal displacement, requiring him to be both French and Senegalese, both colonized and living in a postcolonial Dakar.” The extent to which Sembène was forced to work in and financially depend on France’s bureaucratic system of production, despite being a citizen of independent Senegal, strangely mirrors Diouana’s economic dependence on her employers.

Had Sembène been allowed to make the film as originally intended, he would have created an effect similar to MGM’s The Wizard of Oz (1939), wherein the mythical land of Oz (in this case France) was in color, while other scenes were in monochrome—but in Sembène’s vision, Diouana would have discovered that the shining myth of France was untrue. Nevertheless, his allegory remains sound. He intentionally uses generalized types for his characters to create a political association by which the characters are understood. His French characters have no particular or defining characteristics beyond their race and national identities, but then neither does Diouana. The entirety of France, too, is an obscure object of desire—a myth that remains unattainable. Diouana is stricken with melancholy over her emotional yearning for what Freud would call a “lost object”—her idealized notions of France. As Diouana wanted to claim the cosmopolitan French city for herself, she is troubled to realize she will never experience France. Even more so, the “lost object” for Diouana is her identity, symbolized by the mask. When the French couple hangs the mask on their blank white wall, an oppressive force surrounds the mask—a symbol for Senegal’s relationship with France as well.

Diouana is robbed of her agency through her postcolonial subjectivity, as she’s ostensibly imprisoned in the French home and left to experience what Sembène biographer Samba Gadjigo described as “petit-bourgeois neo-slavery” in France. She has access to the cosmopolitan city before her; however, she remains trapped inside by her demanding employers, while the Madame refuses to let her wander the city without knowing anyone. Of course, she does not know anyone because she is not allowed out to explore the city. Diouana remains a postcolonial subject because she has not escaped the subjectivity of her French employers and cultural colonizers. She also remains inside the apartment because of the limited view she has of her life, which is a view shaped by ideologies of her benefactors. She realizes these forces are always at work inside her, never to be reconciled and, more than feeling trapped between two identities, she acknowledges her fragmentation when she thinks back to her former like in Dakar.

In this sense, the character and her dilemma exist as an allegory for the postcolonial relationship between Senegal and France. Diouana feels a desperate need to escape from her placement in the French apartment, but also from the hold of the French ideology that has complete control over her life. Her methods of escape are grim and heartbreaking, as they involve her memories and, before long, suicide. Sembène’s fate for Diouana is more rooted in classical Greek tragedy than Marxist or anti-colonial political weaponry. Perhaps this is why a mask is an apt metaphor for Diouana. Her identity in the apartment is a shell created by French influences; even in Dakar, her world is inextricably influenced by the French. No matter where she is, a wholeness is impossible. She must wear a mask to be complete. But she refuses to wear that mask. Thus, the physical object of the mask in La noire de… is an essential symbol throughout the film. In Antibes, when Diouana has had enough, she takes the mask back in her desperate attempt to reclaim herself. But the Madame fights with her over it. The two spin in a tugging war, quarreling over the ownership of Diouana’s identity. After taking the mask back, Diouana believes her only recourse is killing herself to ensure her identity is “never again” taken away by the couple. In the final coda, when the boy takes the mask and follows the Monsieur with the mask on, he recoups the false identity as an icon of resistance and of reclamation of identity for Senegal. Indeed, Sembène hopes for a similar cultural reclamation for Senegal from France.

In this sense, the character and her dilemma exist as an allegory for the postcolonial relationship between Senegal and France. Diouana feels a desperate need to escape from her placement in the French apartment, but also from the hold of the French ideology that has complete control over her life. Her methods of escape are grim and heartbreaking, as they involve her memories and, before long, suicide. Sembène’s fate for Diouana is more rooted in classical Greek tragedy than Marxist or anti-colonial political weaponry. Perhaps this is why a mask is an apt metaphor for Diouana. Her identity in the apartment is a shell created by French influences; even in Dakar, her world is inextricably influenced by the French. No matter where she is, a wholeness is impossible. She must wear a mask to be complete. But she refuses to wear that mask. Thus, the physical object of the mask in La noire de… is an essential symbol throughout the film. In Antibes, when Diouana has had enough, she takes the mask back in her desperate attempt to reclaim herself. But the Madame fights with her over it. The two spin in a tugging war, quarreling over the ownership of Diouana’s identity. After taking the mask back, Diouana believes her only recourse is killing herself to ensure her identity is “never again” taken away by the couple. In the final coda, when the boy takes the mask and follows the Monsieur with the mask on, he recoups the false identity as an icon of resistance and of reclamation of identity for Senegal. Indeed, Sembène hopes for a similar cultural reclamation for Senegal from France.

In La noire de…, cultural colonization is also a state of mind, a distance placed between an identity and the splintered identity of colonial subjectivity. For nearly the entire film, the present is represented in France, specifically Antibes. Until the very end, Dakar is only seen through Diouana’s memory-images. These images are not flashbacks in the way that we normally think of them. They are not products of the filmmaker taking us into Diouana’s past to provide us with important narrative information. Instead, they are images projected onto the screen from Diouana’s memory. Dakar has a place in her memory alone, seen in flashbacks of a happier time, complete with a boyfriend, family, and a greater measure of cultural certainty. This is important, as it suggests that Diouana has a constant influx of French cultural influence reshaping her identity by eliminating her cultural origins. Dakar is never whole. Dakar, like Senegal’s pre-colonial identity, or even their current cultural identity in what is supposed to be independence, remains perceived through a series of filters: The oppressive present, the French cultural surroundings, and Diouana’s perspective as a colonized subject.

To portray Diouana’s identity in a constant state of conflict between Senegalese and French influences, Sembène relies heavily on Soviet uses of metaphor and montage. The director studied Soviet techniques in 1962 at the Gorky Studio in Moscow, and he uses devices of Soviet film theory, such as time-images (extended shots of Diouana cleaning), and dialectical montage to convey meaning. For example, by juxtaposing Diouana’s memory-images of Dakar with traditional movement-images that contain narrative information in the present in Antibes, Sembène creates a dialectic between the two, and he directly addresses the social issues impacting his country. Only after Diouana commits suicide does the film return to Dakar. In the present, we see the Monsieur arrive in Senegal and return Diouana’s belongings, and then he’s followed and haunted by the little boy, a character before now seen only in Diouana’s memory-images. Dakar is seen both subjectively (through Diouana’s memory-images) and objectively in the final sequence. The implication is that there is no singular subjectivity in a postcolonial environment. Instead, the Senegalese cultural identity remains in binary, caught between perspectives in an unresolvable tension between the two cultures.

Stylistically, Sembène also directly and intentionally reflects his own fractured postcolonial subjectivity by telling an African story using distinctly French formal techniques. Diouana’s voiceover recalls a tradition of narration in French cinema dating back to the earliest French sound films, particularly those of 1930s Poetic Realism, where characters speak little onscreen outside of their inner thoughts. Film scholar Roy Armes characterized this quality when he compared it to Jean-Pierre Melville’s first film, Le silence de la mer (1949), in which a Nazi official visits the home of a French family that resolves to remain silent throughout the visit, and their silent protest recalls Diouana’s protest against the French couple. Elsewhere, when the film regards the French Riviera or culture, the director uses a generic muzak that recalls Alain Romans’ theme in Jacques Tati’s M. Hulot’s Holiday (1953), another film highly critical of the French bourgeoisie. By contrast, when the film takes us to Dakar or occupies Diouana’s perspective, the score uses African tempos with guitars and bowl drums, music more often associated with Senegalese culture. Sembène’s use of realism—he hired non-actors, used real locations, and delivers flat, unflashy camerawork—also reflects the New Wave cinema emerging in France in the 1960s.

Stylistically, Sembène also directly and intentionally reflects his own fractured postcolonial subjectivity by telling an African story using distinctly French formal techniques. Diouana’s voiceover recalls a tradition of narration in French cinema dating back to the earliest French sound films, particularly those of 1930s Poetic Realism, where characters speak little onscreen outside of their inner thoughts. Film scholar Roy Armes characterized this quality when he compared it to Jean-Pierre Melville’s first film, Le silence de la mer (1949), in which a Nazi official visits the home of a French family that resolves to remain silent throughout the visit, and their silent protest recalls Diouana’s protest against the French couple. Elsewhere, when the film regards the French Riviera or culture, the director uses a generic muzak that recalls Alain Romans’ theme in Jacques Tati’s M. Hulot’s Holiday (1953), another film highly critical of the French bourgeoisie. By contrast, when the film takes us to Dakar or occupies Diouana’s perspective, the score uses African tempos with guitars and bowl drums, music more often associated with Senegalese culture. Sembène’s use of realism—he hired non-actors, used real locations, and delivers flat, unflashy camerawork—also reflects the New Wave cinema emerging in France in the 1960s.

Upon consideration of the film’s themes, it’s continually frustrating to see its title translated to Black Girl in the English language, a troublesome translation to be sure. In French, the original title La noire de… means “the black girl from/of.” Calling the film “Black Girl” is misrepresentative of both the film and the original title. The “de…” of the title is a preposition followed by an ellipsis, suggesting an unknown place of origin, reflecting Diouana’s displacement and fragmented identity in her postcolonial world. By contrast, the English title presents a closed case, its absoluteness determined by its lack of ambiguity. It tells us who she is: a black girl—complete, her origin unquestioned. The French version suggests that black bodies are almost innately sites for cultural fragmentation due to a global history of colonialism and slavery. Diouana is less an individualized character than an allegory for any subject of a postcolonial country. The translated title aside, the film’s use of allegory remains thoughtfully considered, deeply political, and emotionally resonant. Most allegories are often too subtle and lost in the narrative, or they are completely overt and obvious. La noire de… balances emotion and meaning, creating a unique blend of sociopolitical and cultural messages into an aching tragedy.

Bibliography:

Armes, Roy. Third World Film Making and the West. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

Clark, Ashley. “Black Girl: Self, Possessed.” The Criterion Collection. 24 January 2017. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/4402-black-girl-self-possessed. Accessed 8 February 2018.

Diawara, Manthia. African Cinema: Politics and Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992.

Gadjigo, Samba. Ousmane Sembène: The Making of a Militant Artist. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

Malčić, Steven. “Ousmane Sembene’s Vicious Circle: The Politics and Aesthetics of La Noire De ….” Journal of African Cinemas, vol. 5, no. 2, 2013, pp. 167-180.

Rosen, Philip. “Nation, inter-nation and narration in Ousmane Sembene’s Films.” A Call to Action: The Films of Ousmane Sembene, Edited by Sheila Petty. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1996, pp. 27–55.

Woll, Josephine. “The Russian Connection.” Focus on African Films. Edited by Francoise Pfaff. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004, pp. 222–240.

Moolaadé

Moolaadé  Funny Games

Funny Games  Solaris

Solaris