The Definitives

Lawrence of Arabia

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Having journeyed on foot across the Sinai Desert, T.E. Lawrence, played by the indomitable Peter O’Toole, arrives with his sole remaining servant boy at the sanctuary of the Suez Canal. Across the waterway, a man putters along on a motorcycle and slows at the sight of Lawrence and the boy covered in sand and barely standing, the boy waving his arms to call the man’s attention. In a voice dubbed by David Lean, Lawrence of Arabia’s director, the motorcyclist shouts, “Who are you?” Lawrence cannot answer. This decisive question is central to Lean’s 1962 epic, and the filmmaker insisted on asking the question himself. It arises throughout the film, beginning with the first scenes. After Lawrence’s accidental death in a motorcycle crash in the opening, a reporter asks for appraisals of the great T.E. Lawrence on the steps of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, following a memorial service. “He was a poet, a scholar, and a mighty warrior,” one gentleman remarks. “He was also the most shameless exhibitionist since Barnum and Bailey.” By the end of Lean’s picture, each assessment is true, yet all observations fail to scratch the question’s surface.

Lawrence of Arabia tells the story of a tormented hero in an unlikely epic serving not to unabashedly exalt an important historical figure but instead ground the man by removing his pedestal. Even after Lean’s nearly four-hour film, it is impossible to fully explain the character or the film’s brilliance, as there will always be the lingering questions about its hero, who, as Churchill said about Russia, “is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” T.E. Lawrence is complex, uneasy, and filled with neuroses; he is brilliant yet awkward; he values all life but secretly yearns for death; and he is narcissistic yet bent on uniting Arab tribes. Lean’s presentation, an epic tragedy worthy of Homer, dances on the boundaries between history and myth. His picture is not a biography or historical account; it’s a subjective narrative pieced together from Lawrence’s own memory and his historically disputed autobiography Seven Pillars of Wisdom. From this source, Lean investigates a mysticism negating any need for realism. He places the film in the dreamlike world of Lawrence’s head to explore the personal struggle out of which he achieved so much, but also, ultimately, failed.

But then, it’s impossible to ignore is the sheer size and scope of the film, a 70mm spectacle whose panoramic visions of the desert and Lawrence’s Arab revolt still evoke wonder. Shooting at impossibly hot and barren locales in Jordan and Spain, Lean’s superior sense of authenticity and scale permeates in every carefully considered shot. The director’s desire to place his audience in the desert to experience its simultaneous heat and wonderment meant his crew filmed not on soundstages, but places like Al Jafr, unforgiving salt flats about which publicist Howard Kent said, “God has placed it on earth as a warning of what Hell is like.” From these places, Lean captures unimaginable cinematic beauty, such as when a prolonged take awaits a lone rider emerging from a mirage, and Lean maintains several minutes of silent anticipation. The pure enormity of Lean’s frame, not fully appreciated until viewed in a theatrical exhibition, is only matched by the complexity of T.E. Lawrence himself. Both in subject and presentation, the film’s legend hails from Lean’s late-career determination as a filmmaker: “Be bold.”

But then, it’s impossible to ignore is the sheer size and scope of the film, a 70mm spectacle whose panoramic visions of the desert and Lawrence’s Arab revolt still evoke wonder. Shooting at impossibly hot and barren locales in Jordan and Spain, Lean’s superior sense of authenticity and scale permeates in every carefully considered shot. The director’s desire to place his audience in the desert to experience its simultaneous heat and wonderment meant his crew filmed not on soundstages, but places like Al Jafr, unforgiving salt flats about which publicist Howard Kent said, “God has placed it on earth as a warning of what Hell is like.” From these places, Lean captures unimaginable cinematic beauty, such as when a prolonged take awaits a lone rider emerging from a mirage, and Lean maintains several minutes of silent anticipation. The pure enormity of Lean’s frame, not fully appreciated until viewed in a theatrical exhibition, is only matched by the complexity of T.E. Lawrence himself. Both in subject and presentation, the film’s legend hails from Lean’s late-career determination as a filmmaker: “Be bold.”

In his childhood, Lean fancied stories about T.E. Lawrence, a swashbuckling hero donning Arab robes in newspaper stories, where he commanded Arab revolts and sparked the imagination of young readers. Only later would Lean come to learn about Lawrence’s complicated psyche, leaving his boyhood adventure fantasies to be replaced by the foggy psychological makeup that floated around the Lawrence myth that was purveyed by often contradictory biographers. A thin, pale, well-educated man, Thomas Edward Lawrence was born on August 16, 1888, and throughout his life went by many names. He would become known to Arab comrades as Aurens, Lurens, or “Emir Dynamit” (King Dynamite); he also went by the names Shaw, John Ross, Colin Dale, and Smith. He went by so many names that it becomes impossible to know who he is or imagine that he knew himself. After receiving an honors degree in history at Oxford’s Jesus College in 1908, he took a walking tour of Syria and learned Arabic. When World War I broke out in 1914, Lawrence enlisted, despite being five-foot-five and under the standard height for active duty. He quickly volunteered to help the Arab Bureau establish better relations between the Brits and Arabs against their mutual enemy, the Ottoman Turks. By October 1916, he had allied with Prince Feisal, son of Sharif Hussein bin Ali, the Emir of Mecca and self-proclaimed king of all Arabs.

Quickly gaining the trust of Feisal and styling himself as a modern-day crusader in Arab dress, Lawrence aligned himself with various tribes and cutthroats to launch guerrilla assaults on Turkish strongholds, such as the imperative port at Aqaba. His rampant military successes came to a traumatic halt when in November 1917, he was caught spying on the Turkish outpost of Deraa, where he was tortured and sexually assaulted at the orders of the local bey, a regional governor. Soon after, Lawrence was encouraged to persuade Feisal to take Damascus with the promise that, once completed, the British would grant independence to the Arabs and name Feisal as the king of Syria. But, having found oil in Arabia, England and France had already secretly made plans to divvy up the Middle East in the Sykes-Picot Agreement. Lawrence had promised freedom to the Arabs, and now he could not deliver, and so he returned home to numerous medals; however, he felt dishonored for his failure to unite the Arabs. In the meantime, the exploits of T.E. Lawrence had been popularized by American reporter Lowell Thomas, who, in the search for a media hero to distract the masses from the horrors of trench warfare, coined the moniker “Lawrence of Arabia” and presented a colorful traveling picture show to establish T.E. Lawrence as a household name and a hero of schoolboy regard, much to Lawrence’s reproach. Thomas’ show anticipated the saying from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962): “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Seeking anonymity, Lawrence changed his name several times and enlisted in the lower ranks of the Royal Air Force and Tank Corps. At the same time, he also began writing his account of the Arab revolt, calling it Seven Pillars of Wisdom, published in 1926. Within its pages came the first ostensible confirmations of his queer and masochistic tendencies, rumored for years. Lawrence insisted on lifelong bodily privacy, living mostly in his head so few could get close or ever truly know him—not even his closest brother, Professor A.W. Lawrence. Film director and friend Anthony Asquith called Lawrence a “not practicing” homosexual whose close relationship with Arab boy servants is suspect both on and off-screen. In his book, Lawrence wrote about his journey into the desert, a place where his physical agony as a pale Englishman in the extraordinary desert heat served as religious penance, following a medieval feeling that his sins—not to mention the queer drives he had never come to terms with—required physical punishment to be forgiven. According to his brother, T.E. “quelled sexual longings by beatings” and, as biographer Anthony Nutting wrote in The Secret Lives of Lawrence of Arabia, derived sadomasochistic pleasure from suffering. John Bruce, a Scottish soldier Lawrence met in the Tank Corps, admitted later that, until 1935, the year of Lawrence’s death in a motorcycle accident, he carried out ritual floggings with a birch cane at Lawrence’s request. For some scholars, Lawrence’s desire for physical chastisement makes his death suspect; having attempted suicide at one point earlier in his life, Lawrence’s penchant for reckless motorcycling presents itself as a form of unconscious (or perhaps even conscious; Lawrence does seem to smile knowingly in the film) death drive, as if courting his demise.

Seeking anonymity, Lawrence changed his name several times and enlisted in the lower ranks of the Royal Air Force and Tank Corps. At the same time, he also began writing his account of the Arab revolt, calling it Seven Pillars of Wisdom, published in 1926. Within its pages came the first ostensible confirmations of his queer and masochistic tendencies, rumored for years. Lawrence insisted on lifelong bodily privacy, living mostly in his head so few could get close or ever truly know him—not even his closest brother, Professor A.W. Lawrence. Film director and friend Anthony Asquith called Lawrence a “not practicing” homosexual whose close relationship with Arab boy servants is suspect both on and off-screen. In his book, Lawrence wrote about his journey into the desert, a place where his physical agony as a pale Englishman in the extraordinary desert heat served as religious penance, following a medieval feeling that his sins—not to mention the queer drives he had never come to terms with—required physical punishment to be forgiven. According to his brother, T.E. “quelled sexual longings by beatings” and, as biographer Anthony Nutting wrote in The Secret Lives of Lawrence of Arabia, derived sadomasochistic pleasure from suffering. John Bruce, a Scottish soldier Lawrence met in the Tank Corps, admitted later that, until 1935, the year of Lawrence’s death in a motorcycle accident, he carried out ritual floggings with a birch cane at Lawrence’s request. For some scholars, Lawrence’s desire for physical chastisement makes his death suspect; having attempted suicide at one point earlier in his life, Lawrence’s penchant for reckless motorcycling presents itself as a form of unconscious (or perhaps even conscious; Lawrence does seem to smile knowingly in the film) death drive, as if courting his demise.

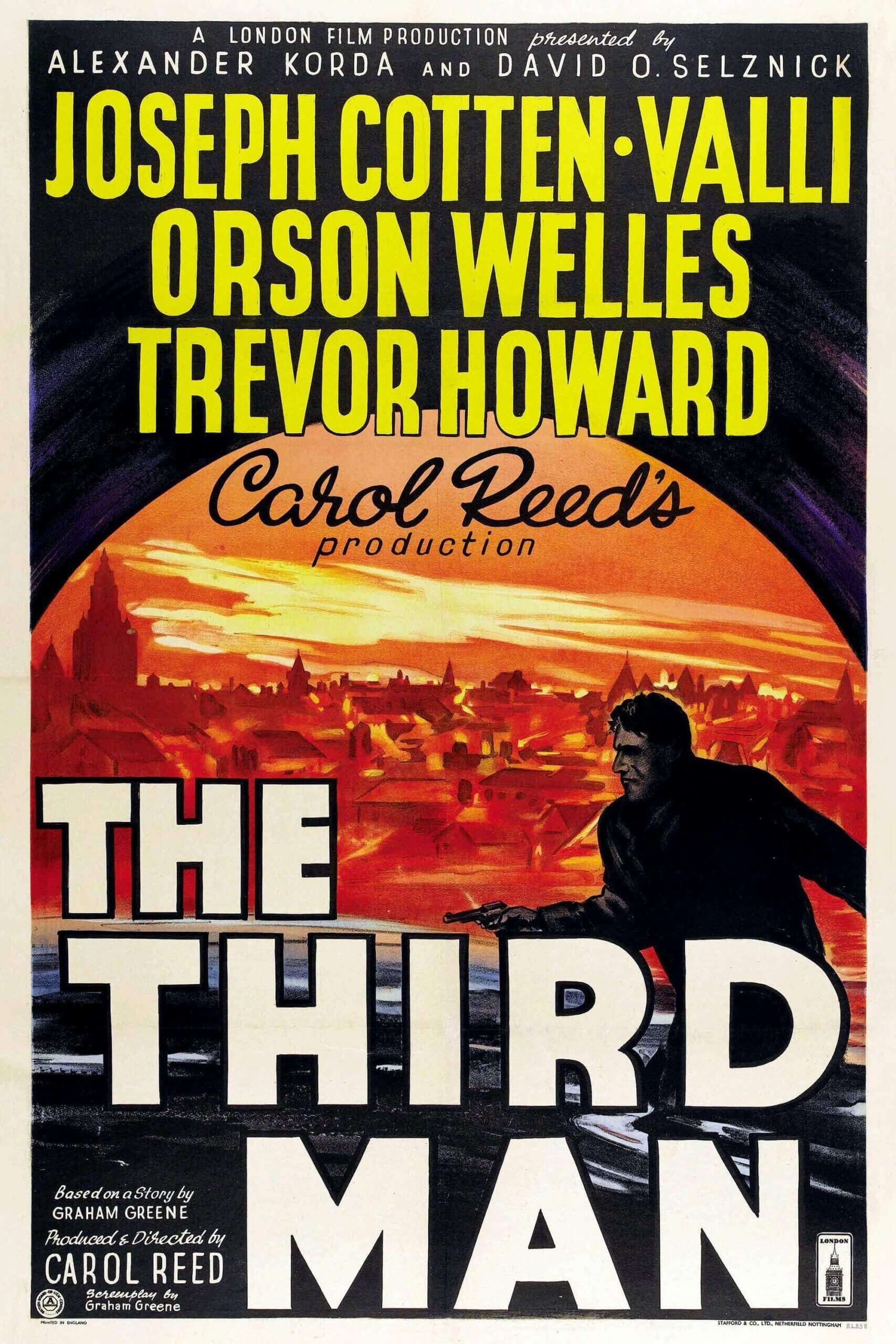

David Lean would not be the first to attempt putting Lawrence’s story to film. Several notable false starts dated back to the 1920s. Lawrence, who held little regard for the “superficial” cinema, had been famously quoted saying, “I loathe the notion of being celluloided.” As early as 1926, Lawrence was approached for a film version of his revolt in the desert. When he refused, thinly veiled fictional versions of Lawrence appeared in the Soviet film Visitor from Mecca (1930) and the adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s play Too True to Be Good (1932). By 1934, Lawrence had been convinced to sell the film rights to Revolt in the Desert, the condensed, mass-market version of Seven Pillars of Wisdom, to Hungarian-born British producer and director Alexander Korda (Rembrandt, 1936), who sought to make a picture starring Leslie Howard and directed by Lewis Milestone. Lawrence at least approved of Leslie Howard’s casting, saying Howard was better looking than he, “which would be an advantage!” By the next year, Lawrence began to question his decision and asked Korda to put off his production until his death, which Korda agreed to, assuming Lawrence simply didn’t want his story filmed. Three months later, Lawrence was dead, but Korda no longer had the financial backing to get the production off the ground. Moreover, Turkey had since become a precarious British ally, and this sensitive political relationship made any film that represented Turkish villains imprudent.

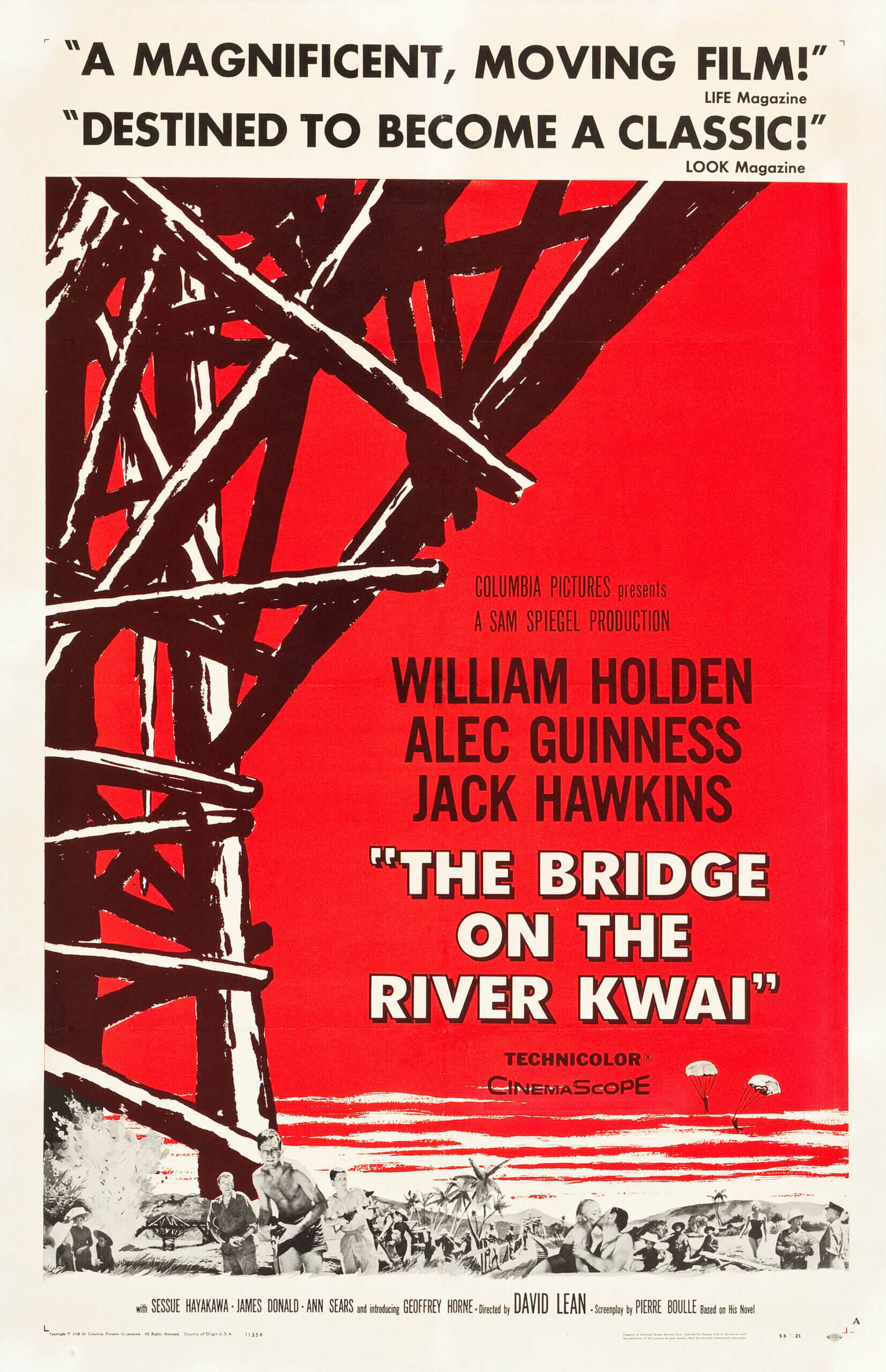

Korda attempted to revive the project in 1938. Other actors considered were Walter Hudd, Cary Grant, Clifford Evans, and Lawrence Olivier; other directors were Brian Desmond Hurst and Harold Schuster. After Korda’s rights to Lawrence’s story expired in 1945, Columbia head Harry Cohn sought British duo Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger (The Red Shoes, 1948) to produce a film, but they turned down the offer. Upon hearing about the attempts to put Lawrence of Arabia’s story to film, David Lean sent a letter to Cohn in 1952 citing his interest in the potential project to be his first film in America. Around this time, screenwriter Terence Rattigan, who wrote The Sound Barrier (1952) for Lean, wrote a screenplay from Basil Liddell-Hart’s authorized biography of Lawrence, but no studio was interested in Rattigan’s “camel opera,” despite securing the interest of director Anthony Asquith (The Browning Version,1951) and actor Dirk Bogarde. Rattigan instead turned his pages into the stage play, Ross, in 1960, which originally starred Alec Guinness as a shyly depicted queer Lawrence. The successful play was to be made into a film, except Sam Spiegel, the Oscar-winning producer behind John Huston’s The African Queen (1951) and Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), had already purchased the screen rights to Seven Pillars of Wisdom the year before and threatened to sue should Ross be put to film. Although the play was not based on Lawrence’s book but rather Liddell-Hart’s biography, Spiegel had created enough legal uncertainty to prevent any forward motion on Ross making it to film. To twist the blade, Spiegel later purchased the film rights to Ross.

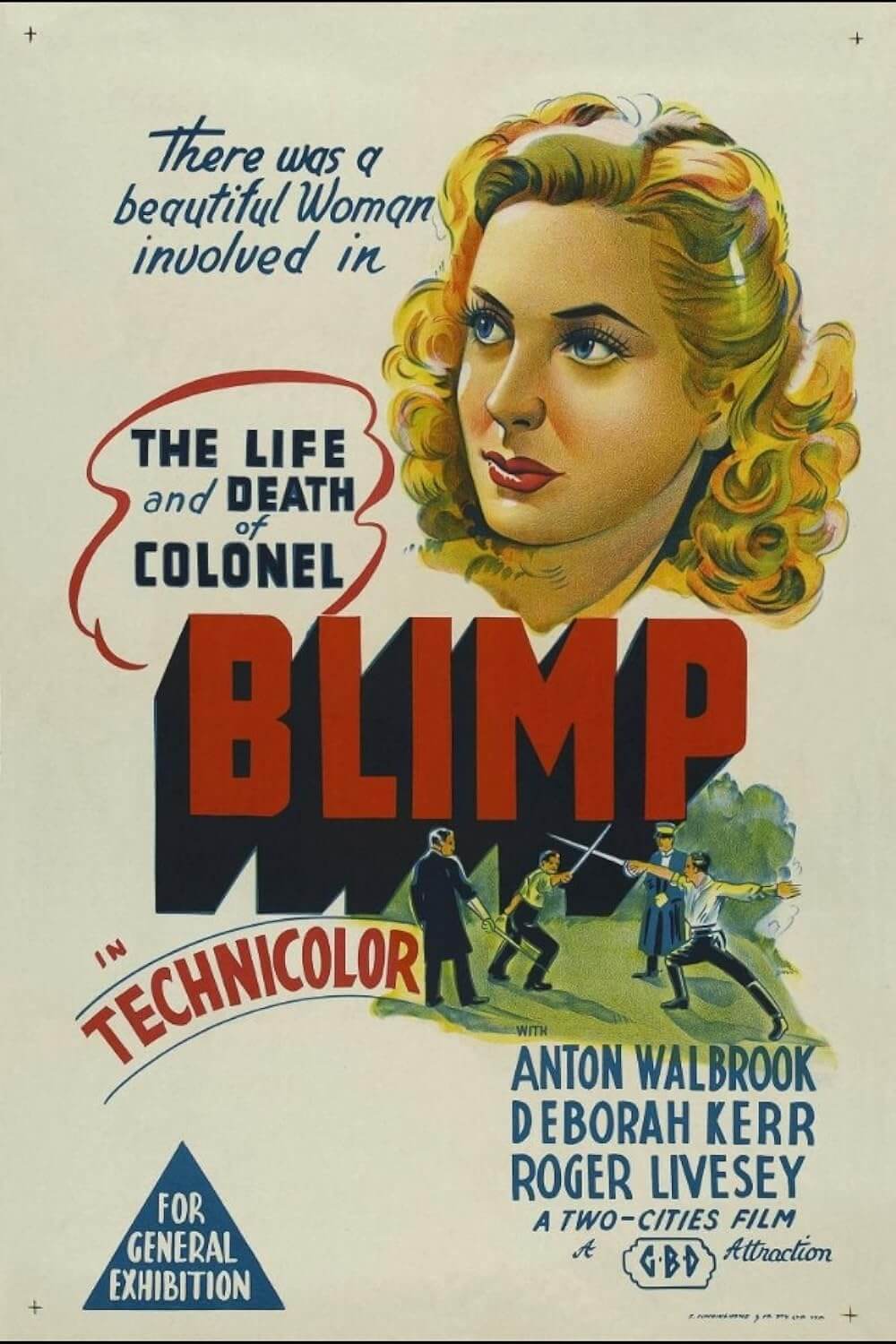

Fortunately, none of these unrealized projects ever went into production. Had a film about Lawrence of Arabia been made any time before the mid-1950s, it may have resembled the traveling movie shows put on by Lowell Thomas, which insisted T.E. Lawrence was a kind of superhero figure. Schoolboys may have enjoyed this kind of wholesome Hollywood adventure, but it would have ignored everything historians and biographers had learned about Lawrence in the interim. The one exception may have been the proposed Powell and Pressburger film, as they had already given substantial dimension to a military figure in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, a film far ahead of its time in 1943. Nevertheless, in 1959, Spiegel hired the blacklisted Michael Wilson, screenwriter of The Bridge on the River Kwai, to pen a treatment for a film about Lawrence of Arabia. Wilson’s initial prose piece titled Lawrence of Arabia: Elements and Facets of a Theme was approved by A.W. Lawrence, the overseer of his brother’s legacy. Spiegel, a Hollywood producer with no end of conceit, and not above reducing himself to crocodile tears or faking a heart attack to get his way, reteamed with his Oscar-winning director of The Bridge on the River Kwai for yet another epic of grand vistas, grander characters, and deep psychological complexity. In February 1960, A.W. Lawrence signed a contract with Spiegel’s Horizon Pictures for the screen rights to Seven Pillars of Wisdom; Spiegel had convinced the inexperienced brother that £22,500 was a fair price, though he probably could have got five times as much.

Fortunately, none of these unrealized projects ever went into production. Had a film about Lawrence of Arabia been made any time before the mid-1950s, it may have resembled the traveling movie shows put on by Lowell Thomas, which insisted T.E. Lawrence was a kind of superhero figure. Schoolboys may have enjoyed this kind of wholesome Hollywood adventure, but it would have ignored everything historians and biographers had learned about Lawrence in the interim. The one exception may have been the proposed Powell and Pressburger film, as they had already given substantial dimension to a military figure in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, a film far ahead of its time in 1943. Nevertheless, in 1959, Spiegel hired the blacklisted Michael Wilson, screenwriter of The Bridge on the River Kwai, to pen a treatment for a film about Lawrence of Arabia. Wilson’s initial prose piece titled Lawrence of Arabia: Elements and Facets of a Theme was approved by A.W. Lawrence, the overseer of his brother’s legacy. Spiegel, a Hollywood producer with no end of conceit, and not above reducing himself to crocodile tears or faking a heart attack to get his way, reteamed with his Oscar-winning director of The Bridge on the River Kwai for yet another epic of grand vistas, grander characters, and deep psychological complexity. In February 1960, A.W. Lawrence signed a contract with Spiegel’s Horizon Pictures for the screen rights to Seven Pillars of Wisdom; Spiegel had convinced the inexperienced brother that £22,500 was a fair price, though he probably could have got five times as much.

The first draft of the screenplay took Wilson eight months to complete. All the while, Lean, who was scouting locations in Jordan, provided him with notes on how to distance their project from the standard romanticized historical biographies of Hollywood’s past. He dissuaded Wilson from too many action sequences and encouraged him to explore Lawrence’s masochism and homosexuality. Lean wanted a character study, not an adventure. Wilson’s structure closely followed Seven Pillars of Wisdom, except he opened the story with a prologue depicting Lawrence’s death and the subsequent memorial service at St. Paul’s, leading to the body of the film: Lawrence leading the Arab revolt and his subsequent failure to secure Arab independence. Although he avoided the usual biographical backstories, Wilson did include an endless array of characters and political situations; his initial script would have made a 7-hour motion picture. Lean, unsatisfied with Wilson’s work and in desperate need of pages to shoot, was frustrated with Wilson’s preoccupation with textbook events and supporting characters. After a year of effort, Wilson gave up after his third draft, convinced Lean was impossible to please.

In the meantime, Spiegel was already looking for another writer. Robert Bolt, whose play A Man for All Seasons (later made into an excellent film in 1966 by Fred Zinnemann) was very well received, found himself in a meeting with Spiegel in January 1961. Bolt initially resisted Spiegel’s offer to write the script, believing motion pictures to be a lesser form of art next to stage plays. Being an expert finagler, Spiegel convinced Bolt to clean up Wilson’s script for a nominal fee. As was often the case on Spiegel productions, few in the cast and crew were paid what they should have been. When Bolt first approached Wilson’s draft, he determined it needed a complete rewrite. Following Seven Pillars of Wisdom and by Spiegel’s order using Wilson’s script for a foundation, Bolt transformed the same narrative structure into a work of human tragedy. Bolt’s talent came in reducing complicated historical events into dramatic matters; he rendered complex situations and philosophies into clear ideas, as seen in A Man for All Seasons. Above all, he was an impeccable dramatist, adding the shot of Lawrence’s motorcycle goggles hanging on a tree branch after his crash; he also included a motorcycle passing by on Lawrence’s journey home at the end, in effect returning the audience to the beginning of the film and reminding us of the character’s accidental death. With his changes, Spiegel demanded Bolt receive sole screen credit.

In Bolt’s hands, the audience learns nothing of Lawrence’s family or upbringing, nor does Bolt’s script describe why this eccentric, often poetic and socially discomfited intellectual joined the army. What we learn of Lawrence is what we observe between the lines or hear in passing as others describe him. His representation of T.E. Lawrence was to be psychologically accurate, while Bolt freely admits to his “triflings with reality.” A.W. Lawrence would later insist the portrayal was untrue, but then he was not present during the Arab revolt. Those who served with Lawrence have confirmed the film’s portrayal is precise. Bolt also tweaked history to fit the dramatic and mythological requirements of the film. He condensed Wilson’s excessive number of characters and oversized length. For example, Bolt’s screenplay largely disregards the actual British involvement in Lawrence’s campaigns; this led to subsequent protests by the British soldiers involved, who were amalgamated into the role of Col. Brighton (Anthony Quayle), while Bolt combined various diplomats into Dryden (Claude Rains). Another example is Gasim (I. S. Johar), the Arab saved from death by Lawrence in the Nefud desert (or “Sun’s Anvil”), whom Lawrence must later kill to prevent a blood feud. Gasim was originally two separate people that Bolt made into one for dramatic effect. Historically, Aqaba was shelled by the Royal Navy before Lawrence’s invasion, making their victory easier than the film represents. But then, Lawrence of Arabia is not a film about places and dates; it is about the character, and from that character the mythos he desired for himself. Therefore it is perfectly reasonable to deem the film less a historical epic than a psychological one that exists, in large part, within the psyche of a complicated and contradictory man. After all, one does not read Homer or Virgil for a factual retelling of the Trojan War.

In Bolt’s hands, the audience learns nothing of Lawrence’s family or upbringing, nor does Bolt’s script describe why this eccentric, often poetic and socially discomfited intellectual joined the army. What we learn of Lawrence is what we observe between the lines or hear in passing as others describe him. His representation of T.E. Lawrence was to be psychologically accurate, while Bolt freely admits to his “triflings with reality.” A.W. Lawrence would later insist the portrayal was untrue, but then he was not present during the Arab revolt. Those who served with Lawrence have confirmed the film’s portrayal is precise. Bolt also tweaked history to fit the dramatic and mythological requirements of the film. He condensed Wilson’s excessive number of characters and oversized length. For example, Bolt’s screenplay largely disregards the actual British involvement in Lawrence’s campaigns; this led to subsequent protests by the British soldiers involved, who were amalgamated into the role of Col. Brighton (Anthony Quayle), while Bolt combined various diplomats into Dryden (Claude Rains). Another example is Gasim (I. S. Johar), the Arab saved from death by Lawrence in the Nefud desert (or “Sun’s Anvil”), whom Lawrence must later kill to prevent a blood feud. Gasim was originally two separate people that Bolt made into one for dramatic effect. Historically, Aqaba was shelled by the Royal Navy before Lawrence’s invasion, making their victory easier than the film represents. But then, Lawrence of Arabia is not a film about places and dates; it is about the character, and from that character the mythos he desired for himself. Therefore it is perfectly reasonable to deem the film less a historical epic than a psychological one that exists, in large part, within the psyche of a complicated and contradictory man. After all, one does not read Homer or Virgil for a factual retelling of the Trojan War.

When Lawrence of Arabia‘s production was first announced, Spiegel confirmed Marlon Brando had been cast as T.E. Lawrence. Brando had since bowed out, choosing instead to play Fletcher Christian in Mutiny on the Bounty (1962). Albert Finney was then courted with four days of screen tests costing upwards of £100,000, and after some deliberation, resolved not to take the role. Finney wanted to be an actor and felt playing Lawrence would turn him into a movie star. Additionally, Spiegel sought to sign Finney to a five-picture deal, and Finney believed this would limit him from accepting the kind of roles he wished to play. Today, Finney’s screen tests are still one of the most requested items stored in the National Film Archive. But Lean suspected that he found his Lawrence during a screening of The Day They Robbed the Bank of England (1960), a heist movie in which the 27-year-old Peter O’Toole plays a British officer in a bit role. During later screen tests, Lean became convinced this no-name actor with undeniable screen presence was his man. O’Toole was cast in the longest film role in history, requiring him to memorize nearly 650 lines. As Lean would discover, O’Toole had wonderful instincts. Take when Lawrence first receives his white Arab robes. He rides off away from the group to enjoy his spoils and, without a mirror, pulls his dagger to observe himself in the reflection of the blade. “Clever boy,” said Lean while filming, having asked O’Toole to improvise a moment of self-satisfaction.

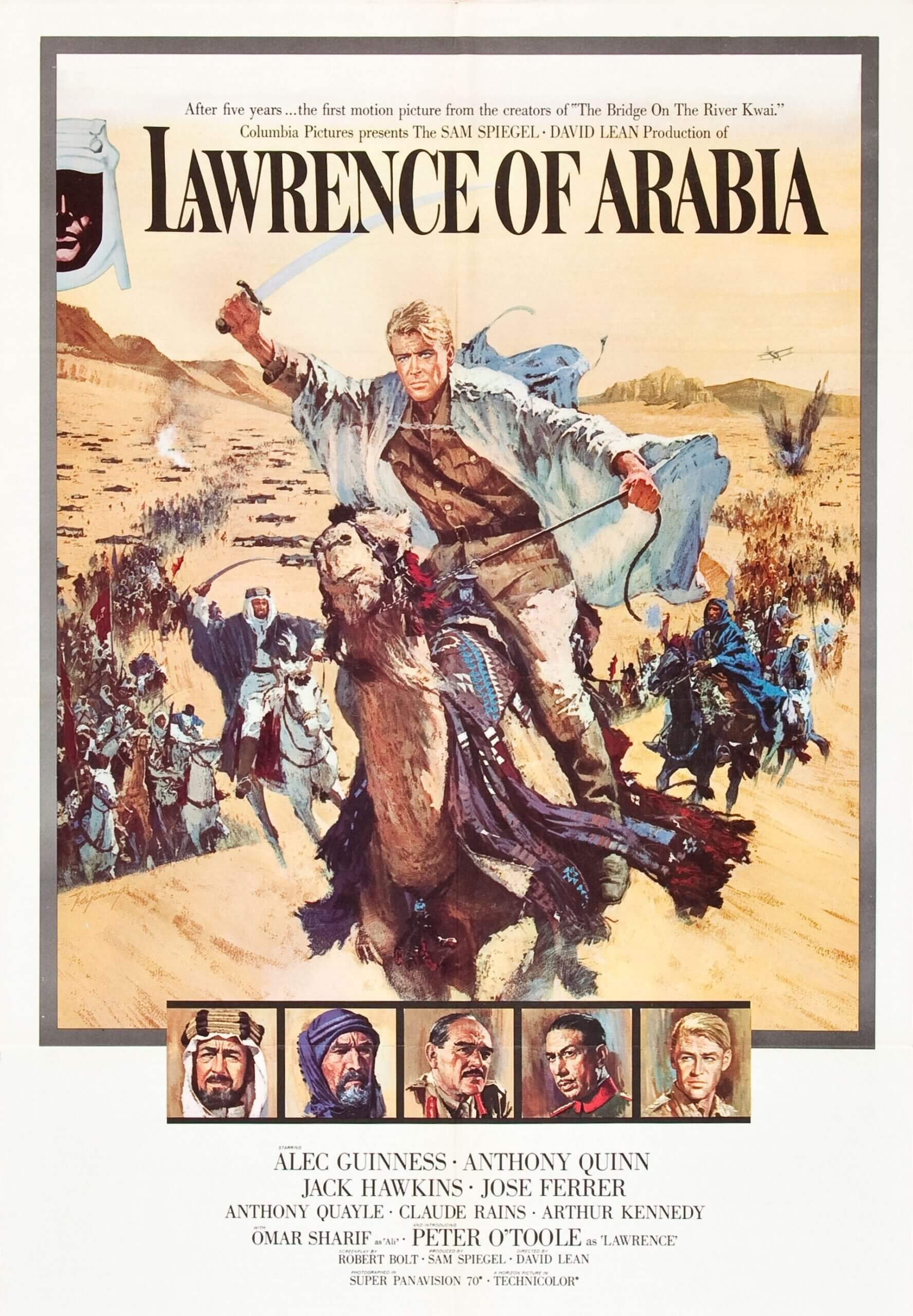

Assigning a relative unknown to such a monumental role set the tone for the rest of Lean’s casting. His picture could have boasted stars like Cary Grant, whom Spiegel wanted for the role of General Allenby, but Lean wanted to avoid Hollywood’s “star system” as much as possible. The ever-reliable Jack Hawkins played Allenby. The major exception was Spiegel’s insistence on casting at least one major box-office draw for American audiences, which Anthony Quinn, having won the Best Actor Oscar for Lust for Life (1956), would provide under a prosthetic bill as Howeitat tribe leader Auda Abu Tayi. Alec Guinness, who had played T.E. Lawrence in Ross, was briefly considered for the lead but was now deemed too old to play Lawrence. Although their quarreling on the shoot of The Bridge on the River Kwai had become legendary, Lean asked Guinness to play Feisal. With this, the director and actor put aside their disagreements and resumed their longstanding friendship. Another reliable actor, Claude Rains, would bring the necessary duplicitous charm to Dryden. Oscar-winner José Ferrer would appear as the notorious Turkish bey who makes pronounced advances at Lawrence until receiving an indignant knee. Finding someone to play Sherif Ali, Lawrence’s closest friend during the Arab revolt, became more difficult. French actors Alain Delon and Maurice Renot were considered for a short time, but after paging through an index of Egyptian actors, Lean found the English-speaking Omar Sharif and cast him after a screen test. Guinness and Sharif became friends, the former using Sharif’s accent as the basis for his Feisal voice. After filming, Lean had become so impressed with Sharif that he asked him to star in his next picture, Doctor Zhivago (1965).

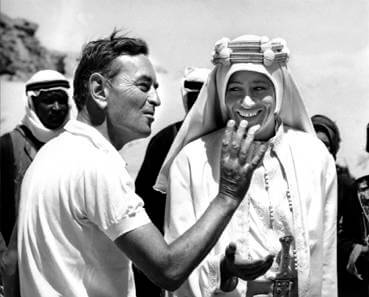

Due to the drawn-out casting process and Bolt’s extensive rewrite, the originally proposed start date in February 1961 was pushed to May 15. They began filming in the Jordanian desert Jebel el Tubeiq, an insufferably remote location for a Hollywood film. The production would not finish until 313 days later in England on September 21, 1962. Cinematographer Freddie Young, working on a 70mm Panavision camera, kept an umbrella over his equipment to prevent overheating; likewise, film stock was kept in a refrigerator—a trick to keep it from warping from the heat. Temperatures were upwards of 120 degrees, but the single biggest problem was smoothing sand between takes. Crewmembers spent hours wiping away footprints left over from the last take before the next one could be filmed. Commanding a 200 person crew and more than 1,000 cast members and extras, Lean shot without the benefit of seeing his daily rushes—Jordon had no suitable facility to view the day’s footage. Whereas today’s filmmakers shoot in front of a monitor, Lean filmed all but blind and was forced to wait four months until he could see the result of his work. Detesting the heat, Spiegel made no more than two visits to the desert location, each time bringing with him a cadre of photographers to take promotional shots that would be released to the press little by little, suggesting Spiegel was there more often than he was. When they weren’t filming, there was nothing for the cast and crew to do in the desert after a long day of shooting except get drunk at a local bar.

Due to the drawn-out casting process and Bolt’s extensive rewrite, the originally proposed start date in February 1961 was pushed to May 15. They began filming in the Jordanian desert Jebel el Tubeiq, an insufferably remote location for a Hollywood film. The production would not finish until 313 days later in England on September 21, 1962. Cinematographer Freddie Young, working on a 70mm Panavision camera, kept an umbrella over his equipment to prevent overheating; likewise, film stock was kept in a refrigerator—a trick to keep it from warping from the heat. Temperatures were upwards of 120 degrees, but the single biggest problem was smoothing sand between takes. Crewmembers spent hours wiping away footprints left over from the last take before the next one could be filmed. Commanding a 200 person crew and more than 1,000 cast members and extras, Lean shot without the benefit of seeing his daily rushes—Jordon had no suitable facility to view the day’s footage. Whereas today’s filmmakers shoot in front of a monitor, Lean filmed all but blind and was forced to wait four months until he could see the result of his work. Detesting the heat, Spiegel made no more than two visits to the desert location, each time bringing with him a cadre of photographers to take promotional shots that would be released to the press little by little, suggesting Spiegel was there more often than he was. When they weren’t filming, there was nothing for the cast and crew to do in the desert after a long day of shooting except get drunk at a local bar.

In September 1961, after 117 days of filming, production was shut down under the pretense that Bolt had yet to finish the second half of the script. The truth was Columbia had grown concerned with the cost of shooting in Jordan; they proposed the production move to Spain. Spiegel had initially assured a staggeringly low $3 million price tag for the film, while more accurate estimates placed the cost at more than $10 million. After a six-week hiatus, filming resumed in Seville, where most of the film’s interiors were captured. Despite delays, the prolonged production was neither indecisive for Lean’s part nor wasteful, as on most days the director knew exactly what he wanted. But, much like his ponderous episodes on the set of The Bridge on the River Kwai, occasionally Lean would sit for hours, almost catatonic, waiting for his next idea. Still, an impressive level of planning was required, such as shooting the film’s first half in sequence to allow O’Toole to grow into the tormented character T.E. Lawrence would become. Young intentionally staged shots from left to right throughout the film to emphasize the theme of Lawrence’s psychological journey, the most impressive among them being the invasion of Aqaba, shot from a peak in Almeria where Young captures the entire march in one take. To keep the shooting schedule at pace, Spiegel ordered second-unit director André De Toth (director of the 1953 B-movie House of Wax) and his cameraman Nicholas Roeg to film the train derailing sequence. De Toth later quit his post at the head of Lean’s second-unit, and Roeg took over (Roeg would go on to direct Walkabout (1971) and Don’t Look Now (1973)). Lean, who ruled his quiet, ever-serious set like an autocrat, despised having to relinquish control to his second-unit.

Roeg would later note how Lean demanded “obedience over allegiance” on the set. Still, like many great-yet-tyrannical masters of cinema, ranging from Alfred Hitchcock and Akira Kurosawa, Lean’s level of perfectionism was arguably justified by the end result, even if he was occasionally saddled with a label such as “dedicated maniac.” That Lean was drawn to the story of T.E. Lawrence seems so obvious today. Mirroring Lawrence, Lean had grown passionate about putting himself through impossible trials to complete films about obsessive characters. On The Bridge on the River Kwai, a film about two fanatical military ideals clashing in a POW camp, Lean spent more than six months shooting in a sweltering jungle with conditions so unbearable union crews eventually stopped work to protest. While filming Lawrence of Arabia, Lean was accused of being, like his subject, a “desert-loving Englishman” and seemed to take masochistic pleasure from filming in such a remote, unforgiving location. Lean’s complexion quickly transformed from pale to dark brown with his time in the desert sun, and his refusal to wear goggles that would protect his eyes from dangerous desert winds gave way to embedded grains of sand that required surgery to be removed from his eyelids. Whether Lean shared his subject’s masochistic desires or not remains unknown. Still, the process of putting himself in a situation that is in some ways comparable to the one in his film seemed a desirable and necessary component for Lean’s most powerful work.

Lasting almost as long as the Arab revolt, principal photography took 16 months in all. Spiegel finally secured an end when he set the film’s London and New York premiere dates without Lean’s approval, leaving Lean no choice but to comply and finish the picture. The final scenes filmed were Lawrence’s motorcycle crash and subsequent memorial scenes, both captured in England. With a few short months before the December premiere, editor Anne Coates and Lean sat down in their London office to edit countless hours of footage, working seven days a week from 9 a.m. to midnight to assemble the finished picture. According to Coates, Lean transformed from a dictatorial director to a pleasant fellow in the editing room, having earned renown early in his career as a ruthlessly precise and skilled editor. Coates quickly gained Lean’s professional confidence by making choices he too would have made. Her most famous contribution occurs in Dryden’s office just before Lawrence goes to the desert in the beginning. The sequence begins with a close-up of Lawrence; he lights a match and, as he blows it out, Coates cuts to a Sahara sunrise. The sun peeks behind the desert horizon, the sand blazing in deep oranges as the yellow orb rises, revealing the immensity of the landscape, and thus the impossibility of one man somehow conquering its vastness. This gorgeous sequence might sum up the entire film.

Lasting almost as long as the Arab revolt, principal photography took 16 months in all. Spiegel finally secured an end when he set the film’s London and New York premiere dates without Lean’s approval, leaving Lean no choice but to comply and finish the picture. The final scenes filmed were Lawrence’s motorcycle crash and subsequent memorial scenes, both captured in England. With a few short months before the December premiere, editor Anne Coates and Lean sat down in their London office to edit countless hours of footage, working seven days a week from 9 a.m. to midnight to assemble the finished picture. According to Coates, Lean transformed from a dictatorial director to a pleasant fellow in the editing room, having earned renown early in his career as a ruthlessly precise and skilled editor. Coates quickly gained Lean’s professional confidence by making choices he too would have made. Her most famous contribution occurs in Dryden’s office just before Lawrence goes to the desert in the beginning. The sequence begins with a close-up of Lawrence; he lights a match and, as he blows it out, Coates cuts to a Sahara sunrise. The sun peeks behind the desert horizon, the sand blazing in deep oranges as the yellow orb rises, revealing the immensity of the landscape, and thus the impossibility of one man somehow conquering its vastness. This gorgeous sequence might sum up the entire film.

At first, choosing someone to score Lawrence of Arabia was no choice at all. Lean wanted Malcolm Arnold, who won an Oscar for his The Bridge on the River Kwai score; Spiegel wanted even more prestige and hired British composer William Walton to work with Arnold. Given a two-hour rough cut to view, Arnold and Walton fell asleep and laughed at what they saw, leaving Spiegel to find someone else for the job. Spiegel wanted an “Oriental” score and tapped Richard Rodgers, Broadway composer for The King and I, to write it. French composer Maurice Jarre, who had just written the music for another Spiegel investment, was hired to orchestrate. Rodgers wrote samples (including an inappropriately titled “Love Theme,” inappropriate because there is no outright love story in the film) without even seeing footage from the film. None of Rodgers’ music fit, whereas Jarre had his own ideas. Jarre played sections out of what he called “The Theme from Lawrence of Arabia,” and Lean hired him on the spot. Jarre was given only six weeks to write music for conductor Sir Adrian Boult of the London Philharmonic. Boult quickly discovered he hadn’t the precise timing necessary to conduct a film score, and Jarre took over, even though Boult received final screen credit. In addition to his own music, Jarre used sections from Kenneth Alford’s march “The Voice of the Guns,” just as Arnold’s score for The Bridge on the River Kwai used Alford’s “Colonel Bogey March.” Among the most memorable of all film scores, Jarre’s theme of roaring cymbals and haunting strings inhabits the mysticism and mystery of the desert, the Middle East, and T.E. Lawrence, but also the lavishness of this epic film. Jarre would score every subsequent David Lean film.

Lean and Coates finished the final cut just before the London premiere, delivering a three hour and forty-two-minute version. Separated into two halves by an intermission and entr’acte, the screen story begins, as noted, with Lawrence’s death and subsequent memorial at St. Paul’s. Cut to Cairo during World War I, where lowly British Army lieutenant Lawrence, known for his shyly impudent airs and knowledge of Bedouin culture, makes maps. The Arab Bureau’s Dryden convinces Lawrence’s superior to send him into the desert to evaluate the potential of a revolt against the Turks. There, going against the orders of his British liaison, Col. Brighton, Lawrence impresses Prince Feisal with his knowledge of Arab culture and ease with the desert and proposes an attack on the port city of Aqaba, its guns faced toward the Red Sea. Lawrence suggests approaching from behind, through the impassable Nefud Desert, with the element of surprise. With fifty of Feisal’s men under his command and joined by Bedouin guide Sherif Ali, as well as two servant boys Daud (John Dimech) and Farraj (Michel Ray), Lawrence’s group survives the Nefud, only to find that a single man, Gasim, has fallen behind. Lawrence braves the Sun’s Anvil once more to save Gasim and returns a hero; he is awarded the honorary white robes of a sherif. Taking rest at a watering hole, they are confronted by its owner, Auda Abu Tayi of the Howeitats, whom Lawrence convinces to join their cause. Before attacking Aqaba, a blood feud between Feisal’s men and the Howeitats threatens to destroy their alliance and make taking Aqaba impossible. Lawrence resolves to pacify the fuel by killing the wrongdoer, only to discover it is Gasim. Nevertheless, he pulls the trigger, and together the tribes take Aqaba. After, Lawrence, joined Daud and Farraj alone, resolves to trudge the Sinai Desert to Cairo and ask for munitions and money to support the Arab revolt. Upon arriving back in “civilized” territory, with just Farraj in tow, Daud having died in quicksand, Lawrence surprises General Allenby with his victory. Lawrence confesses to Allenby that he remains disturbed by the pleasure he felt from gunning down Gasim. To answer Feisal’s suspicions, Lawrence asks if the British have any ambitions in Arabia, and Allenby denies it. In a later chat with Dryden, Allenby confirms the first rumblings of the Sykes-Picot Agreement.

After the intermission, we return to find Lawrence deep into a guerilla war. American war correspondent Jackson Bentley (Arthur Kennedy, playing a fictional version of Lowell Thomas) covers his progress. Lawrence has lost himself in the confidence spawned from repeated victories, where nicknames like “King Dynamite” go to his head. He is reminded of his mortality when he is shot in the arm after derailing a train and again when he must euthanize the mortally wounded Farraj as another train sabotage goes wrong. With such missteps, Lawrence’s men begin to question his exalted status. The final blow comes when he is captured in Deraa by the local bey; he is tortured and sodomized by the sneering guards and afterward tossed in the mud, suggesting he has been despoiled. Now beleaguered and hesitant to return to the desert, Lawrence is convinced by Allenby to take Damascus, that his Arab army will join because T.E. Lawrence is leading the charge. Instead, Lawrence finds he must pay a ruthless band of murderers to pad his ranks. On the road to Damascus, they spy Turkish soldiers fleeing after having raided a village. Out of vengeance and bloodlust, Lawrence follows his men’s call for “No prisoners!” and orders much the same. Only in the aftermath does he realize what bloodshed has resulted from his command. On to victory at Damascus, where Lawrence hopes to undermine the Sykes-Picot Agreement by establishing an Arab council to control the city; rather, he finds the bickering and in-fighting Arab tribes cannot join together against their common rival, in turn leaving the city for British rule under an Arab flag. Lawrence is promoted to Colonel and dismissed by Allenby and Dryden. No longer needed, Lawrence is ordered home.

After the intermission, we return to find Lawrence deep into a guerilla war. American war correspondent Jackson Bentley (Arthur Kennedy, playing a fictional version of Lowell Thomas) covers his progress. Lawrence has lost himself in the confidence spawned from repeated victories, where nicknames like “King Dynamite” go to his head. He is reminded of his mortality when he is shot in the arm after derailing a train and again when he must euthanize the mortally wounded Farraj as another train sabotage goes wrong. With such missteps, Lawrence’s men begin to question his exalted status. The final blow comes when he is captured in Deraa by the local bey; he is tortured and sodomized by the sneering guards and afterward tossed in the mud, suggesting he has been despoiled. Now beleaguered and hesitant to return to the desert, Lawrence is convinced by Allenby to take Damascus, that his Arab army will join because T.E. Lawrence is leading the charge. Instead, Lawrence finds he must pay a ruthless band of murderers to pad his ranks. On the road to Damascus, they spy Turkish soldiers fleeing after having raided a village. Out of vengeance and bloodlust, Lawrence follows his men’s call for “No prisoners!” and orders much the same. Only in the aftermath does he realize what bloodshed has resulted from his command. On to victory at Damascus, where Lawrence hopes to undermine the Sykes-Picot Agreement by establishing an Arab council to control the city; rather, he finds the bickering and in-fighting Arab tribes cannot join together against their common rival, in turn leaving the city for British rule under an Arab flag. Lawrence is promoted to Colonel and dismissed by Allenby and Dryden. No longer needed, Lawrence is ordered home.

At a private screening for A.W. Lawrence before the premiere, A.W., no doubt expecting a factual and historical account of his brother’s legacy, stood up aghast and shouted at Spiegel, “I never should have trusted you!” Taken aback by the film’s exploration of his brother’s masochism and implied homosexuality, A.W. published a protest of Lawrence of Arabia in the London Observer. In an open letter, Spiegel responded and suggested A.W. did not recognize his brother because he did not know “Lawrence of Arabia.” He only knew T.E. Lawrence. In attendance at the London premiere on December 10, 1962, was the Queen and the Royal Family, along with a healthy cross-section of British talents and celebrities. Their receptions were overwhelmingly enthusiastic, with fellow director Fred Zinnemann saying it was “out of my league.” Never one to pass up an opportunity for a joke, Noël Coward, who had collaborated with Lean on several pictures during the 1940s, quipped that if O’Toole had looked any prettier in his Arab garb, “The picture would have had to be called Florence of Arabia.” The early reception in the U.S. was just as fervent. Lean’s favorite was the “attentive” Los Angeles audience, who, in his assessment, seemed to recognize what a substantial work it was immediately. Although O’Toole’s breakthrough performance became the main talking point for the press, interviewing the often drunken actor was another prospect entirely. The following April at the Academy Awards ceremony, Lawrence of Arabia won seven of its ten Oscar nominations, including awards for Lean as Best Director, Spiegel for Best Picture, Freddie Young’s cinematography, composer Maurice Jarre, Anne Coates’ editing, John Box’s production design, and John Cox’s sound editing. Conspicuously absent from the winners was O’Toole, who it is believed lost to Gregory Peck for To Kill a Mockingbird because of his perpetual inebriation during post-release interviews.

Just after the New York premiere, legendary producer David O. Selznick warned Lean that MGM had asked him to shorten his initial cut of Gone with the Wind (1939). “Tomorrow morning, you’re going to start getting phone calls from people telling you to cut it. Don’t do it!” Lean’s initial cut ran 222 minutes, and like clockwork Spiegel and Columbia implored Lean and Coates to reduce the picture’s length. Following initial roadshow engagements, Lean reduced Lawrence of Arabia to 202 minutes for its wide release, making cuts “with a scalpel, not an axe,” insisting audiences would never notice. Years later, in 1970, Columbia and Spiegel made additional cuts for the television debut, reducing the length to 187 minutes, all with Lean’s approval. However, Lean disapproved of the picture’s re-release into theaters in 1971 in its abridged television cut. Some twenty-five years later, film archivist Robert Harris received Columbia’s permission to restore Lawrence of Arabia to its original length. Aided by Lean and Coates, Harris headed the painstaking charge of handling warped film prints and rifling through countless cans of film stock to track down footage that had gone missing over the years. One sequence was missing the audio track, requiring O’Toole and Guinness to redub their lines a quarter-century after the fact. The majority of the restored footage consists of establishing and transition shots and no full sequences. Additionally, Lean, always the editor, made a few trims, reducing the length from 222 to 217 minutes. He considered this his “director’s cut,” and the restored version premiered in February 1989, and every subsequent theatrical reissue and video release has featured this version.

Of Lawrence of Arabia, Omar Sharif once noted, “It was a very expensive film, with no love story. No action really. If you come to think of it, no great battles. Just a lot of Arabs going around the desert on camels, and the leading character was an anti-hero.” Indeed, nothing about the film qualifies for a conventional Hollywood biopic. Though exotic, the film’s desert landscape is far from a traditionally beautiful, exotic movie locale. The protagonist remains hidden from the audience, his character flaws mining dark territory. O’Toole’s T.E. Lawrence is shown to be capable of vengeful bloody murder, intense egoism, delusions of grandeur, and violent self-atonement. His convictions are not resolved, nor does he “save the day” and return home to his faithful bride, as a classic movie hero might. He does not die honorably in battle; rather, he is cheated of his dignified death by his own character flaws. Like the opposing Colonels Nicholson and Saito in The Bridge on the River Kwai, Lawrence is determined to surmount the impossible, only to be revealed as a deluded, self-obsessed, dogmatic man doomed by his inner conflicts. This recurring theme in Lean’s films finds characters refusing to accept defeat even when all reasonable chance for victory has been compromised. It is the quality that makes these characters great but also makes them mad.

Of Lawrence of Arabia, Omar Sharif once noted, “It was a very expensive film, with no love story. No action really. If you come to think of it, no great battles. Just a lot of Arabs going around the desert on camels, and the leading character was an anti-hero.” Indeed, nothing about the film qualifies for a conventional Hollywood biopic. Though exotic, the film’s desert landscape is far from a traditionally beautiful, exotic movie locale. The protagonist remains hidden from the audience, his character flaws mining dark territory. O’Toole’s T.E. Lawrence is shown to be capable of vengeful bloody murder, intense egoism, delusions of grandeur, and violent self-atonement. His convictions are not resolved, nor does he “save the day” and return home to his faithful bride, as a classic movie hero might. He does not die honorably in battle; rather, he is cheated of his dignified death by his own character flaws. Like the opposing Colonels Nicholson and Saito in The Bridge on the River Kwai, Lawrence is determined to surmount the impossible, only to be revealed as a deluded, self-obsessed, dogmatic man doomed by his inner conflicts. This recurring theme in Lean’s films finds characters refusing to accept defeat even when all reasonable chance for victory has been compromised. It is the quality that makes these characters great but also makes them mad.

More than just unconventional, Lean’s representation of T.E. Lawrence is nothing short of provocative in intimate ways that were missed by many upon its release. Subtle, intentional symbolism throughout the picture establishes Lawrence’s growing view of himself as a god-like figure, namely a desert sun god, and Lean staged scenes with O’Toole standing before artistic renderings of the Sun or the actual Sun positioned behind him like a halo. Nevertheless, Lawrence is also a pious man plagued by sexual, certainly homosexual drives and a desperate need to suppress them. His kinship with the two servant boys goes beyond implication. The torturous pleasure he derives from his rape at the Turkish bey’s order infers not only his homosexuality but also his masochistic tastes. In Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence wrote of Arab soldiers “thirsting to punish appetites they could not wholly prevent” and undoubtedly learned from them. When Lawrence and the bey face each other, our hero is stripped down and his pale flesh pinched by the bey; Lean cuts to the bey’s wet lips and Lawrence’s inflamed, fearful eyes. Shots of leering soldiers precede his rape and torture, which cuts away to Sherif Ali outside, waiting for hours for them to finish. Whereas earlier in the film, a viewer might dismiss Lawrence’s “trick” of putting out a match’s flame with his finger, this is the seed of his masochism; his explanation that “the trick is not minding that it hurts” could not be more revealing. After the episode of his rape, Lawrence lashes out in his bloodiest campaign on the road to Damascus.

Where better for a man such as this to go than the brutal desert? Here, a burning sun rains down pain with every ray of daylight. Out of his natural habitat of chill and rainy Britain, this Englishman must travel extraordinary distances by ostensibly fasting with limited food and water, every journey an agony, allowing him to regard himself as a modern Moses. Physical punishment is part of the environment, but the desert also implies Lawrence’s extreme isolation, metaphorically and literally. A desert is a place where a man who feels alone among his own kind can feel in control and lose himself in whatever fantasy he desires. He looks up at the desert’s clear night sky, glowing with the brightest stars imaginable. At this sight, Lean remarked later that he understood why all the major religions began in the desert. When the Arabs accept Lawrence as a leader sent from the heavens to defy what is written through his will, he was given extraordinary power but no guidelines for using it, so he loses himself. The desert remains a seemingly vacant space where a traveler such as Lawrence must find a point and cling to it to arrive safely, but, despite loving the desert, he disregards its full panoramic view. Lean reveals that Lawrence failed to completely grasp the desert’s mysticism in his attempt to control it, imparting that Lawrence failed to understand the desert and thus failed to overcome his own demons.

Within the boundless purview of visual splendor and uncommon tragedy, Lean engages in a profoundly psychological character study that would redefine cinema’s extravagant historical biographies forevermore. At first, only the film’s grandeur, its technical perfection, the sheer size of the 70mm image within the frame stand out. Then Lean’s orchestration of the scope and intuitive visuals; O’Toole’s remarkable breakthrough performance, the best of his career and perhaps of all time; Jarre’s haunting and Orientalized score; and Bolt’s concise and intimating dialogue emerge. And yet, the film is greater than the sum of its parts. Its Citizen Kane-esque question asks, Who is this man? Except unlike Orson Welles’ 1941 film, Lean does not offer an equivalent solution to Rosebud. Answers in Lawrence of Arabia are subtle, implied, and must be read, if not projected. The film leaves a myriad of questions and challenges the viewer to understand its complex, perhaps unknowable subject. This motion picture is unlike any epic because after enduring so many perils in an enormous journey, the size of which had never been seen in a Hollywood production, the questions about T.E. Lawrence remain. But such unanswerable questions are what have brought audiences back to the picture again and again over the years, and what make Lawrence of Arabia an enduring, incomparable epic.

Within the boundless purview of visual splendor and uncommon tragedy, Lean engages in a profoundly psychological character study that would redefine cinema’s extravagant historical biographies forevermore. At first, only the film’s grandeur, its technical perfection, the sheer size of the 70mm image within the frame stand out. Then Lean’s orchestration of the scope and intuitive visuals; O’Toole’s remarkable breakthrough performance, the best of his career and perhaps of all time; Jarre’s haunting and Orientalized score; and Bolt’s concise and intimating dialogue emerge. And yet, the film is greater than the sum of its parts. Its Citizen Kane-esque question asks, Who is this man? Except unlike Orson Welles’ 1941 film, Lean does not offer an equivalent solution to Rosebud. Answers in Lawrence of Arabia are subtle, implied, and must be read, if not projected. The film leaves a myriad of questions and challenges the viewer to understand its complex, perhaps unknowable subject. This motion picture is unlike any epic because after enduring so many perils in an enormous journey, the size of which had never been seen in a Hollywood production, the questions about T.E. Lawrence remain. But such unanswerable questions are what have brought audiences back to the picture again and again over the years, and what make Lawrence of Arabia an enduring, incomparable epic.

Bibliography:

Anderegg, Michael. David Lean. Twayne, 1984.

Brownlow, Kevin. David Lean: A Biography. St. Martin’s, 1997.

Lawrence, T.E. Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Triumph: The Complete 1922 Text. Wilder Publications, 2011.

Maxford, Howard. David Lean. Batsford, 2000.

O’Connor, Garry. Alec Guinness: Master of Disguise. Hodder & Stoughton, 1994.

Phillips, Gene. Beyond the Epic: The Life & Films of David Lean. The University of Kentucky Press, 2006.

Pratley, Gerald. The Cinema of David Lean. Barnes, 1974.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review