The Definitives

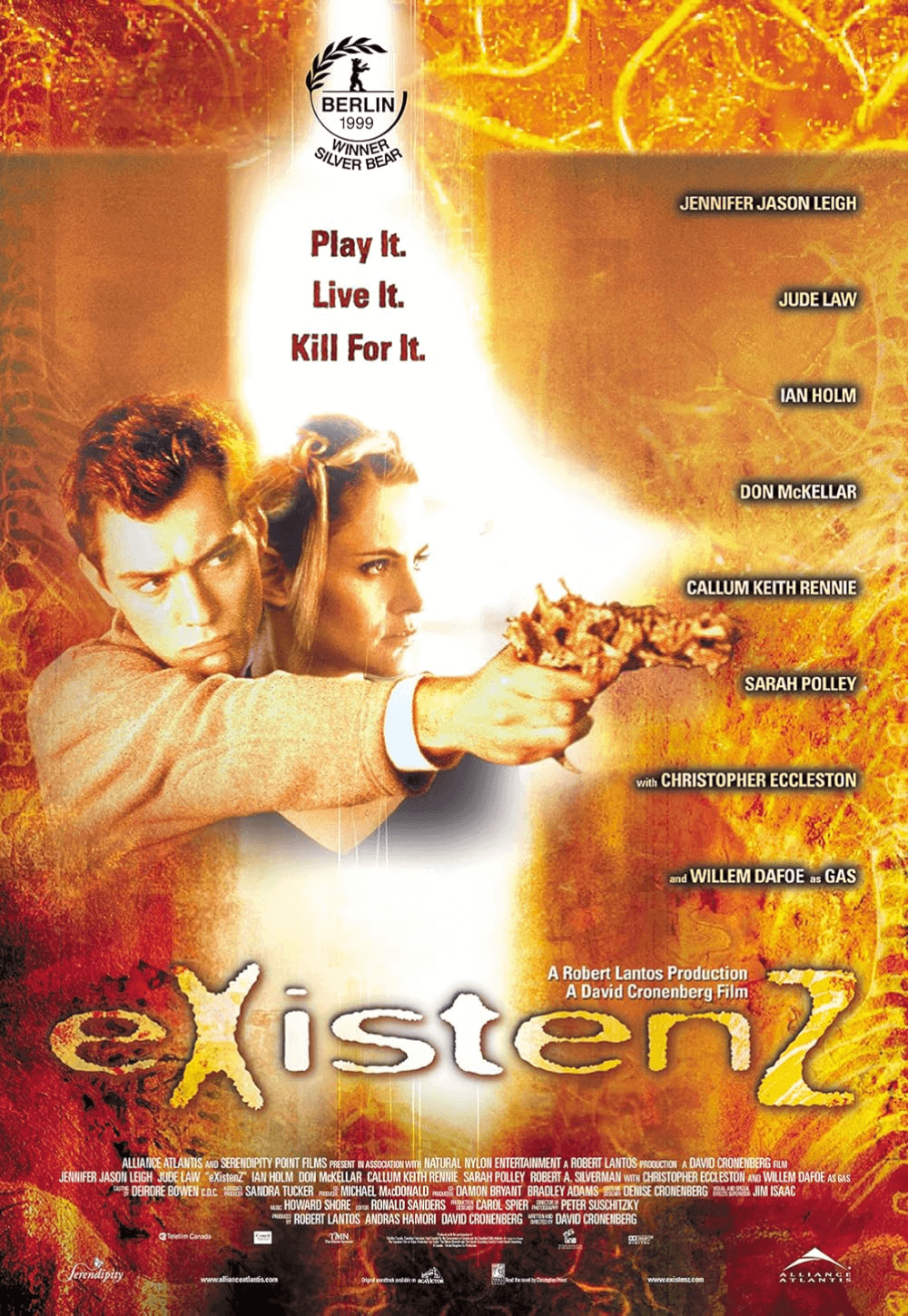

eXistenZ (1999)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

An early scene in eXistenZ finds game designer Allegra Geller, played by Jennifer Jason Leigh, wandering around the parking lot of a country gas station—named Country Gas Station, funnily enough. As though investigating an alien world, she sniffs the petroleum, delights in kicking up dirt, and smiles with conspiratorial appreciation after tossing a stone at the gas tank and hearing the resultant clank. Upon first viewing, the viewer might wonder what this inconsequential scene is about, if anything. Only after the film has ended, when Cronenberg reveals that Allegra and others were playing a game called transCendenZ all along, does it come together. Any gamer knows that seemingly banal actions take on new meaning when presented through an artificial lens. Shopping, sleeping, eating, performing chores, and all of those things that might seem tedious in everyday life become fascinating details to explore because they were designed for the player to experience. Games that feature massive open worlds or offer meticulous character customizations receive praise for their ability to replicate minor details and tasks that add to the overall realistic texture of the game world. The more inconsequential the specifics, the more convincing the illusion. In this scene, Allegra does something familiar for many gamers; she pauses her role in the game narrative to test how real her surroundings feel, relishing the attention that went into designing this virtual world.

Like many of David Cronenberg’s films, eXistenZ is another in the Canadian auteur’s long line of vivid, wholly original visions about technology’s role in the human experience. His 1999 feature considers how reality and media are interconnected, with a comic self-referentiality that confronts the quirks in video games and cinema. Although the setup involves a game designer, Allegra, on the run from an underground faction of Realists intent on executing her for committing crimes against the human mind, Cronenberg’s scenario delves into the blurring lines between reality and its virtual alternatives in media. His narrative structure contains recursive loops that double back to reframe the viewer’s understanding of what has occurred so far, occupying a game-within-a-game-within-a-game logic that causes heads to spin. However, Cronenberg’s mindbender operates with more intentionality than the many VR and game-related films of the 1990s, offering a philosophical treatment of concepts that would presage the methods and commentaries about video games in the near future. eXistenZ anticipates massive multiplayer worlds that boast photoreal graphics and cinematic storytelling, crafted by celebrity game designers whom the public either aggrandizes or demonizes. From this, Cronenberg taps into debates about the possibilities and limitations of video games and whether they can be art, while also questioning the nature of reality itself.

Reserved and intense, Allegra Geller previews her new game, eXistenZ, for a batch of volunteers at a promotional event in the film’s first scene. A living organism rather than a cold, plastic console filled with microprocessors, her game reflects the player’s ambitions, fears, and desires until reality and mimesis prove indistinguishable. That’s a problem for the Realists who bungle an assassination attempt at the preview, prompting Allegra to head underground with Ted Pikul (Jude Law), a “marketing trainee” for Antenna Research, the game distributor with millions invested in Allegra’s game. Warned by a company rep (Christopher Eccleston) to “Trust no one,” Allegra and her out-of-his-depth compatriot head to the countryside, sporadically populated with game enthusiasts who may help or double-cross her to collect the bounty on her head. While concerned for her life, Allegra also worries about her game system. She must play it “with someone friendly” to ensure it’s healthy and running properly. Drawing from Allega and Pikul’s recent experiences, the game, his first, puts them in a corporate espionage thriller similar to what’s happening in their real world. And while inside, the lines between reality and simulation overlap.

Similar to everything from Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983) to Crimes of the Future (2022), eXistenZ presents a twisting spy scenario rife with double agents, creatives, and various corporate interests (Antenna Research and Cortical Systematics) vying for market control. At one point in Allegra’s game, Pikul sums up the experience: “We’re both stumbling around together in this unformed world whose rules and objectives are largely unknown, seemingly indecipherable, or even possibly non-existent, always on the verge of being killed by forces that we don’t understand.” But Cronenberg doesn’t design his film like many of his contemporaries. Rather than a near-future world envisioned with ultramodern details, he and his regular production designer, Carol Spier, set the events in the countryside, where old buildings, barns, and rundown structures replace the sci-fi genre’s characteristic sleek and metallic designs. Cronenberg omits the usual computer screens, shiny clothes, and flying vehicles for something more timeless in Allegra’s MetaFlesh Game Pod, a convincing practical effect that, according to the script, shakes like a “terrified hamster” in distress. Besides the game, the only new technologies onscreen consist of Pikul’s “pink phone,” a formless blob that glows when pressed, along with some tablet-like devices resembling iPads used by game testers in the final sequence.

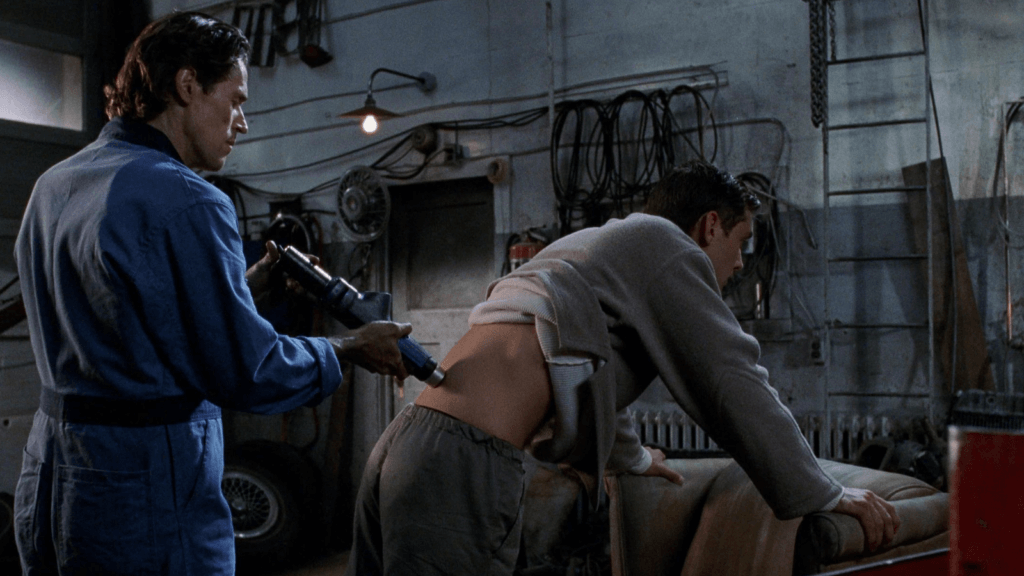

Inevitably, Cronenberg links his new technology to the body and sex. Players “port in” to the game not through a controller but their Bioport, an orifice installed near the lower spine that accesses their nervous system using a long UmbyCord. Pikul refuses to get a Bioport installed, given his phobia about having his body “penetrated.” He worries about a Bioport infection because it opens “right into your body.” Allegra smiles and tells him not to be ludicrous. Then she gives him a look down her throat, reminding him of the body’s various holes. Allegra soon convinces him to get the installation, and almost immediately, the Bioport becomes another site for sexuality, to be licked, lubed, and fingered. His Bioport even “wants action,” according to Allegra. Yet, Pikul’s worries about infection aren’t unfounded; Bioports can be infected, such as when contagious spores transmit from Allegra’s game into Pikul like an STD. To his credit, Cronenberg avoids turning the sexualized dynamic between Allegra and Pikul into conventional exploitation, which may not have been true had the director made the film earlier in his career. He consciously avoids typical gender roles by having Allegra convince Pikul to allow himself to be penetrated. “They do it at malls, like getting your ears pierced,” she says. Cronenberg acknowledges that if the roles were reversed, with a male designer plugging into a female marketing trainee, “It would have been crude.” However, the director lamented that, because Pikul is a worrying and “subservient” character, casting him was difficult, as many young actors don’t want to appear weak or feminized. Law, just at the start of his career, gives a wonderful, convincing performance, complete with a Canadian accent, as a man with frantic anxiety over his new orifice and its various states of contamination and infection. Much of the film’s unlikely humor springs from his nervy performance.

Although Cronenberg has never made outright comedy, his films, particularly those he had a hand in scripting—eXistenZ and Crimes of the Future above all—feature comic moments built around macabre or uncannily absurd circumstances. Consider one of Allegra’s admirers, a gas station operator named Gas; Willem Dafoe plays him with a goofily maniacal grin when Gas goes on about “God, the mechanic,” in reference to her earlier game, ArtGod. Or note the sudden, unprovoked slap Gas issues to the back of Pikul’s head after he pulls a shotgun on Allegra and Pikul, like a parent smacking his child, further infantilizing Pikul. Elsewhere, Allegra critiques her game after encountering D’Arcy Nader (Robert A. Silverman), a bizarre game entry-point character. She amusingly calls him “Not a very well-drawn character. His dialogue was just so-so,” as though echoing the viewer’s thoughts on Silverman’s characteristically oddball acting. Nondescript signage—such as “Motel” and “Country Gas Station” and “Chinese Restaurant” instead of specific names—also underscores the amusing disharmony between the game’s convincing sensory effect and small details that hint at the players’ in-game status. Some of the humor doesn’t reveal itself until after finishing eXistenZ. When one of Allegra’s allies, Kiri Vinokur (Ian Holm), kills a Realist with a bone gun that shoots teeth, he states, “My dog brought me this.” It’s a nonsensical statement, until you realize, after the transCendenZ session reveal, that Allegra and Pikul are the Realists who have hidden pistols on a shaggy dog that has accompanied them to the game testing.

To be sure, Cronenberg’s humor sometimes registers as strangeness when first watching eXistenZ, before the viewer learns of the stacked simulation-within-a-simulation setup, but it becomes ever more apparent, funny, and rewarding on subsequent viewings. But it’s not without purpose. The director’s ironic self-referentiality acknowledges the mechanics of clunky game devices and movie narratives. One scene finds Allegra and Pikul forced to “jump each other,” indicating how cinema will often deploy a “pathetically mechanical attempt to heighten the emotional tension” with a scene of romance or sex despite there being no chemistry between the characters. Much of eXistenZ plays out that way, with the in-game mechanics driving a narrative using plot devices typical for games and movies. When the finale unveils the transCendenZ focus group in the church, the players—many of the actors spied throughout the film—comment about their indecipherable accents and game logic, suggesting that all of the perceived flaws with the performances and storytelling throughout Cronenberg’s film were intentional and part of a self-reflexive commentary. Moreover, the players of transCendenZ by PilgrImage exist in a more grounded, less Cronenbergian world where the game tech is a blue, inorganic, stereotypically futuristic gizmo worn on the head and hand.

The initial idea for eXistenZ emerged in a script for MGM about the future of video games, Cronenberg’s first wholly original screenplay since the similarly themed, TV-centric Videodrome. For years, Cronenberg had been adapting books such as Stephen King’s The Dead Zone, counterculture texts from William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch to J. G. Ballard’s Crash, and the book Twins for Dead Ringers (1988), inspired by real-life identical twin gynecologists. He also adapted David H. Hwang’s play M. Butterfly and the 1958 B-movie The Fly. However, the deal with MGM for eXistenZ would fall through; the studio had come back with too many notes on Cronenberg’s script. They didn’t want the game designer to be a woman, because, according to their understanding of demographics, sci-fi movies appeal to young men who want to see themselves reflected onscreen. “Feminist so-called paranoia about Hollywood is absolutely justified,” Cronenberg later told Sight and Sound. MGM also wanted a more “linear” movie, which, for Cronenberg, was missing the point. When the filmmaker and studio reached a stalemate, Cronenberg left negotiations and developed the project with a Canadian company, Alliance Atlantis, which had made his 1996 feature, Crash.

During the writing phase, Cronenberg wanted to avoid his work becoming “a meditation on the virtual-reality genre,” given the omnipresence of the subject in 1990s cinema. Emerging technologies, philosophical debates, and social anxieties fuelled the topic of virtual reality in Hollywood movies throughout the 1990s, though many of these ideas wouldn’t extend beyond the hypothetical or theoretical. While Nintendo, SEGA, and many other major gaming companies tried to get VR technology into the marketplace but failed because they couldn’t get the technology right, Hollywood could dream up all sorts of possibilities in mostly underwhelming fare such as The Lawnmower Man (1992), Arcade (1993), Ghost in the Machine (1993), Brainscan (1994), Johnny Mnemonic (1995), Strange Days (1995), Virtuosity (1995), Open Your Eyes (1997), and Dark City (1998). These examples each explore, to varying degrees of success, the threat of technology impacting, invading, or replacing reality. It’s a fear epitomized by Y2K and the dread that, come the year 2000, computer calendars would switch to double-zeroes and either erase all databases or remain stuck at 11:59 at midnight on December 31, 1999. The terror over technology’s capacity to reshape the literal with the digital ultimately proved unheeded. The year 2000 came and went without much consequence.

eXistenZ was released in late April of 1999, a defining year for virtual reality in cinema. A few weeks earlier, in late March, The Matrix debuted and showcased the Wachowskis’ hugely successful cyberpunk blend of martial arts, pop philosophy, entrenched trans metaphors, and breakthrough special effects, which the masses consumed in droves. The first installment established a franchise and quickly implanted its imagery and themes into the zeitgeist. Given a limited release after The Matrix, Cronenberg’s film looked modest and unflashy by comparison. Although the director received the Silver Bear for Outstanding Artistic Contribution at the 49th Berlin International Film Festival for eXistenZ, the lukewarm critical reception of his film, combined with the underwhelming box-office numbers, meant his project would be overlooked in favor of the Wachowskis’ vision. In May of 1999, German director Josef Rusnak released The Thirteenth Floor, another movie about a VR world and a loose take on Daniel F. Galouye’s novel Simulacron-3 (1964) and Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s miniseries World on a Wire (1973). Although the hackneyed storytelling receives no support from a cast of stilted performances, the result looked Matrix-like enough with its green digital imagery to drive people to theaters, if not in droves, then enough to out-perform Cronenberg’s film.

Even so, what sets eXistenZ apart from its contemporaries is Cronenberg’s meditation on the role of the artist in video games, as opposed to a concentration on the potential of virtual reality. The director admitted to film writer Chris Rodley that his initial ideas “crystallized” after an interview he conducted with Salman Rushdie in 1995 for the Canadian magazine Shift. Rushdie had authored the novel The Satanic Verses, published in 1988 and inspired by the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Early the following year, Ayatollah Khomeini, leader of Iran, issued a fatwa against Rushdie and his publisher, calling for their assassination. After the fatwa was issued, Rushdie spent a decade in hiding in London and then New York. Although Rushdie issued an apology in 1990, the fatwa remains irrevocable, and as recently as 2022, Rushdie survived an assassination attempt. In Cronenberg’s 1995 interview with Rushdie, their discussion turned to video games and the extent to which they could be art. The director called them “democratic art” in that the player is equal to the creator of the game, rather than the game designer using their medium to express something. Between Cronenberg’s existing work on the eXistenZ script and this conversation, the director rethought his film, turning Allegra into a Rushdie-esque character hunted by the “Realist underground.” Vinokur even remarks about a “ridiculous story about some fatwa” against Allegra.

Other aspects of the Rushdie interview feed into eXistenZ. When Allegra attempts to convince Pikul that their game session won’t be unfairly tipped to her advantage, she says, “You could beat that guy who invented poker, couldn’t you?” This suggests her game is a democratic one, perhaps less so than ArtGod, an earlier game that connects the player with the artist and god— “‘Thou, the player of the game: ArtGod,’” reflects Gas. “Very spiritual.” But Allegra’s new game is something different. There is no intended point, unlike most art. “You have to play the game to find out why you’re playing the game,” she says. In his conversation with Rushdie, Cronenberg questions whether such a democratic approach should be considered art. Rushdie argues, “A work of art is something which comes out of somebody’s imagination and takes a final form,” and only in that state of completion is it rendered as art. By contrast, a game in which the player has control and can change the outcome isn’t a form of art. Then again, Rushdie concedes to “never say never” about the possibility of games as art. Cronenberg even admits, “I could see that there could be an artist of a games player, a kind of Michael Jordan of the Nintendo.” Cronenberg may have predicted the world of Twitch and celebrity gamers.

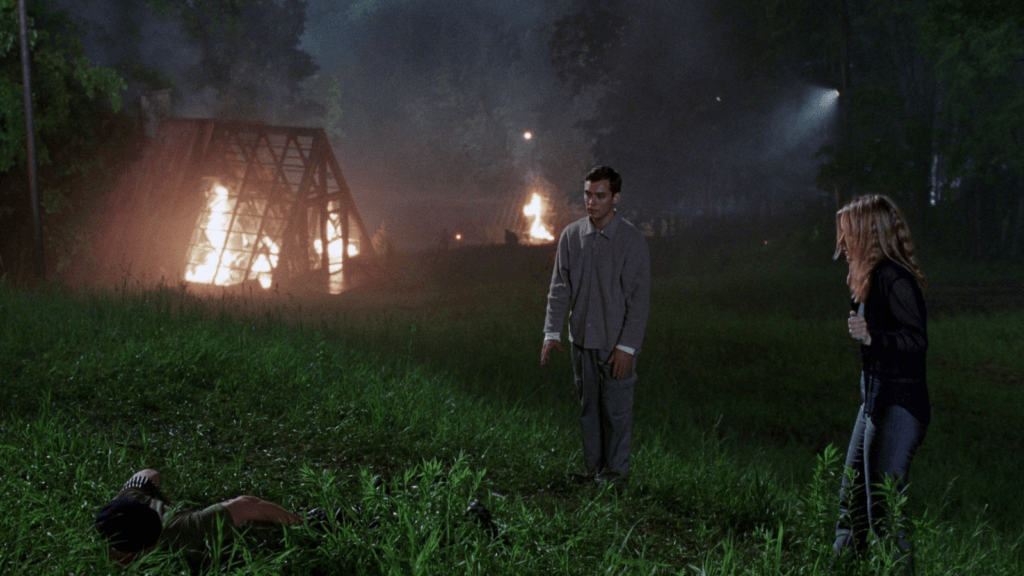

Having played games such as Myst, Gadget, and Super Mario Bros. by 1995, Cronenberg envisioned an alternative game without a preordained trajectory or scripted plot. Rather, eXistenZ improvises and draws from the players’ experiences, crafting a story from their unconscious minds and giving them the illusion of control. Allegra’s game architecture supplies a foundation, but her game’s players enrich the material with just enough free will “to make it interesting.” In this sense, Allegra is less the artist of eXistenZ than the builder of a foundation that allows the player to become the artist. Depending on the player’s creative drives, they might have a central part or a more passive, supporting role in the game’s action. Alternately, the game takes over at specific points. Inside Allegra’s game at the Chinese Restaurant, Allegra and Pikul are instructed to order the Special—a gooey display of slimy mutant amphibian parts that Pikul, compelled by the game and not his desire, proceeds to eat to gag-inducing effect. As he consumes various pieces, he assembles a pistol from the leftover bones, which is undetectable by scanners. The game wants him to build the gun and shoot the Chinese waiter (Oscar Hsu), but the notion of a gun and the shaggy dog who runs away with the weapon after the killing have been drawn from the real Pikul’s subconscious. Later, after the reveal that everyone’s been playing transCendenZ, designed by Yevgeny Nourish (Don McKellar), and that Allegra is just a player, she acknowledges that the game must have picked up on her ambition to design games. In transCendenZ, Allegra is an artist. However, the real Allegra is also part of the Realist underground, instilling a warped irony that she is a skilled game player yet resolves to assassinate Nourish and his assistant Merle (Sarah Polley).

If the player’s role as an artist remains fluid in eXistenZ, the designer’s role is linked to religion, performing the function of a godlike entity who creates the world and allows others to inhabit it. It’s no coincidence that Antenna Research arranged the sneak preview session in a church after hours. The audience of fans sits in pews, cheering with fanatical enthusiasm when Allegra first appears. When she leads the group through a tour of her game, her twelve apostle-like volunteers sit around her in an arrangement evoking Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of the Last Supper, while her devoted congregation watches, waiting for their turn. This worshipful relationship is part of the problem for the Realists, who blame game designers for “the most effective deforming of reality” and deem Allega a “demoness” for her contributions. For her part, Allegra does not refer to herself as a god or deity. Her behavior toward her game pod, the twitching, fleshy thing she carries throughout the film, has motherly associations. She refers to the pod as “my baby” and addresses it using female pronouns; she even displays protective, affectionate behavior toward the thing, caressing and fondling the game pod in a warped blend of parent and lover.

More than any other film in Cronenberg’s career, eXistenZ also reveals author Philip K. Dick’s influence on the director’s recurring themes: uncertain realities, corporate espionage, technology gone wrong, and fanatical religious belief. At various points in his career, Cronenberg considered adapting Dick’s novel A Scanner Darkly and Ubik for the screen. He spent a year writing a dozen drafts of a script based on the author’s short story “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” for producer Dino De Laurentiis—the two clashed over results, and the project eventually went to Paul Verhoeven to become 1990’s Total Recall. In eXistenZ, Cronenberg’s inclusion of Pikul’s fast food from a place called Perky Pat’s nods to Dick’s 1963 short story, “The Days of Perky Pat.” It’s an apt reference to a tale about survivors of a nuclear apocalypse who escape from their grim reality with a doll named Perky Pat. Just as the characters in Dick’s story rely on a consumer product to process and escape from reality, so do the players of eXistenZ, underscoring humanity’s attraction to artificial constructs. Moreover, Dick’s tendency to write about artificial worlds, conveyed via dreams, drugs, or technology (in Time Out of Joint, Ubik, et al.), has had an unquestionable impact on Cronenberg’s more sci-fi-centric output.

Like many of Dick’s stories, eXistenZ poses lingering questions about the nature of reality. Allegra wants to liberate her players from the confines of their limited reality: “Break out of your cage, Pikul. Break out now.” She sees reality as a trap that players escape by experiencing an alternate reality in her game, describing people as “programmed to accept so little. But the possibilities are so great.” Gas, for instance, operates a gas station “only on the most pathetic level of reality.” In Allegra’s games, Gas or anyone else can become anything they dream of. Perhaps it goes without saying that eXistenZ expresses Cronenberg’s affinity for existentialist theories—the notion that life itself is meaningless and the absurd universe has no inherent purpose, apart from how people imbue their experiences with meaning. The film’s questions about reality and virtual reality force its characters to confront the absurdity of their existence and address whether they have real freedom. At the same time, the scenario underscores the importance of personal choice, with Allegra and Pikul navigating the game while simultaneously informing how the game will play out.

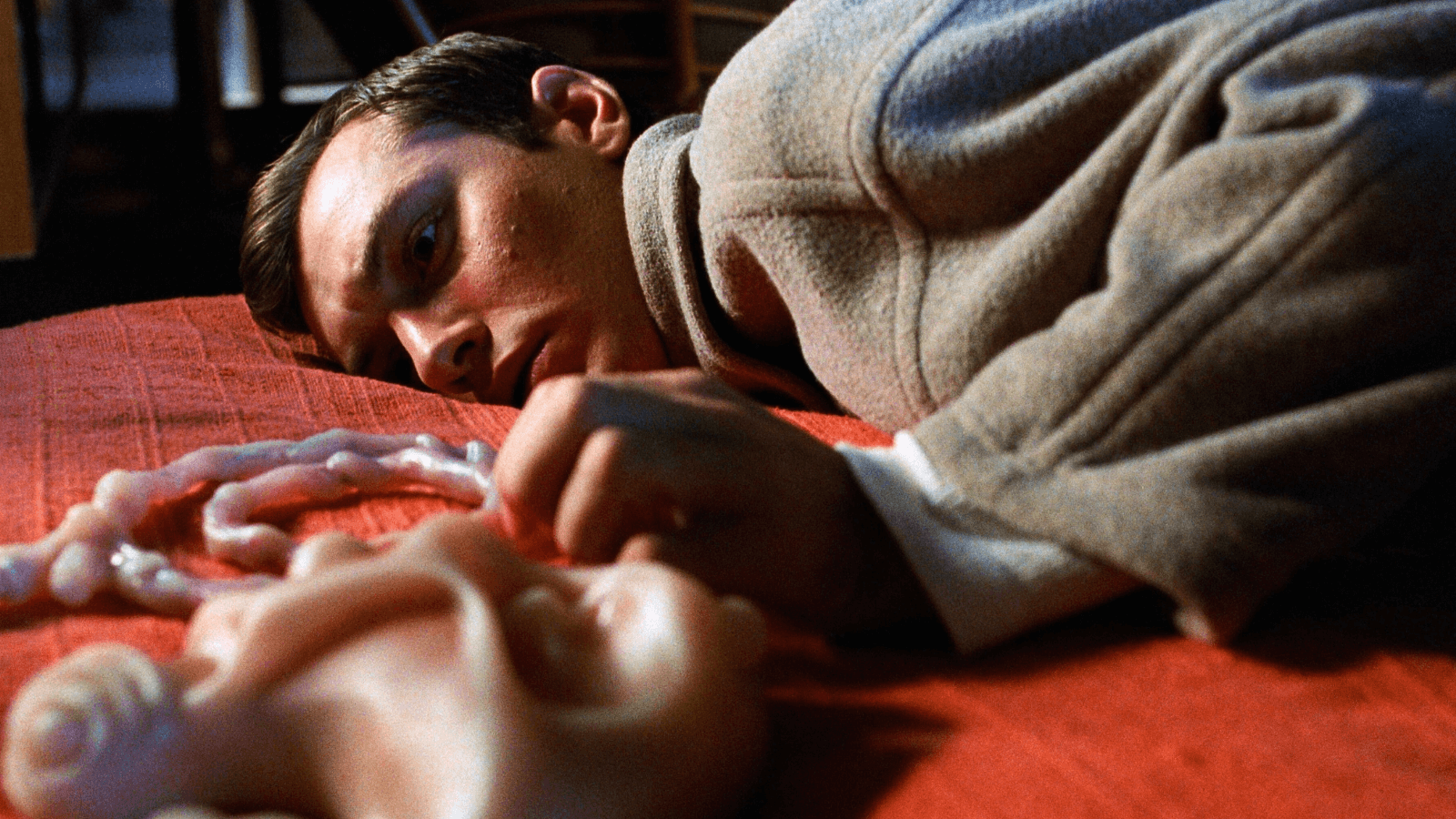

The film’s conflict stems from Allegra’s game and its potential to distort reality, confusing the distinction between reality and her game’s simulation. Unlike the other VR-related movies from this era mentioned above, eXistenZ presents its simulation without a subpar CGI plane and blocky, pixelated animation. Aside from the occasional stilted behavior and dialogue of game characters, along with the inclusion of occasional mutant amphibians, there’s no telling these worlds apart. While playing Allegra’s game, Pikul even wants to pause their progress because “there’s an element of psychosis here.” He’s distracted by the identical world and its details, and he worries about his body, though it rests peacefully on a bed next to Allegra. This is familiar material for Cronenberg, who has explored how engaging with media has the potential to supplant reality (see Videodrome, Naked Lunch). The three-tiered reality in eXistenZ leaves its characters unsure if they’re still in the game. The Realists opposed to Allegra’s game see only danger, believing that she has deformed reality by confusing players and unintentionally instilling the paranoid belief in simulation theory. “See the problem?” says Callum Keith Rennie’s revolutionary when Pikul expresses concerns that he’s not sure whether or not they have left the game.

Ever ahead of its time and unique in its consideration of games and virtual reality, eXistenZ could be seen as a precursor to many similarly themed Hollywood productions in the subsequent decades. Similar to Pikul feeling detached from his body while playing Allegra’s game, James Cameron’s Avatar (2009) tells the story of a paraplegic hero who “plugs in” to his Na’vi counterpart, losing touch with his human body and, ultimately, abandoning it to commit to his alien body fully. Christopher Nolan’s Inception (2010), about corporate spies infiltrating the dreams of their targets, features a similar narrative structure of story threads stacked onto each other, echoing one another, albeit with dream layers instead of the layers built into transCendenZ. Just as in eXistenZ, each layer in Inception functions on a separate plane, and the deeper down one goes into one’s unconscious mind, the slower time passes. The same is true of Nourish’s game: “If you stayed your whole life in the game world, then you could live to about, I don’t know, 500 years,” says Silverman’s transCendenZ player. What is more, the events in one dream layer impact the others in Nolan’s film, recalling how Allegra and Pikul bring back a disease from inside her game. “There’s a very weird reality-bleed-through effect happening here,” she remarks. “I’m not sure I get it.”

eXistenZ presents as a twisting science-fiction yarn about virtual reality, video games, corporate espionage, reality extremists, and cultish fandom. On those terms, few other films compare to its singular but modest production values, thoughtful performances, resonant music by Howard Shore, and intentional cinematography by Peter Suschitzky that anticipates the look of many cutscenes in video games. At a deeper thematic level, Cronenberg proves more concerned with the relationship between art and reality. The director told Rodley, “Art is a scary thing to a lot of people because it shakes your understanding of reality, or shapes it.” Art has long been the topic of debate and concern, going back to Plato’s warnings that mimesis threatens to undermine reality. “As a card-carrying existentialist,” Cronenberg said, “I think all reality is virtual. It’s all invented. It’s collaborative, so you need friends to help you create a reality. But it’s not about what is real and what isn’t.” The film serves the same function as the film’s game—it liberates players, allowing them to realize that reality is a construct, informed by social conditioning, belief systems, various takes on culture and civilization, technology, and art. After Allegra and Pikul assassinate Nourish for “the most effective deforming of reality,” there’s a moment of disquiet. Hsu’s transCendenZ player asks meekly, “Hey, tell me the truth. Are we still in the game?” Cronenberg might argue that it doesn’t matter.

(Note: This essay was commissioned and originally posted to Patreon on September 24, 2024. A special thanks to Lyra for suggesting this title. It’s a personal favorite of mine. Thank you, Lyra, for your continued support and patronage!)

Bibliography:

Beard, William. The Artist as Monster: The Cinema of David Cronenberg. University of Toronto Press, 2006.

Browning, Mark. David Cronenberg: Author or Filmmaker? Intellect, Ltd., 2007.

Cronenberg, David. “Cronenberg meets Rushdie.” Shift 3.4, June-July ’95.

Guthmann, Edward. “A Deeply Creepy `eXistenZ’ / Cronenberg’s horror films move the genre to uncanny new places.” SFGATE, 25 April 1999. https://www.sfgate.com/entertainment/article/A-Deeply-Creepy-eXistenZ-Cronenberg-s-horror-2934355.php. Accessed 8 September 2024.

Mathijs, Ernest. The Cinema of David Cronenberg: From Baron of Blood to Cultural Hero. Wallflower Press, 2008.

Rodley, Chris, editor. Cronenberg on Cronenberg. Faber and Faber, 1992.

—. “Game Boy.” Sight and Sound, April 1999. http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/feature/149. Accessed 8 September 2024.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review