Nuremberg

By Brian Eggert |

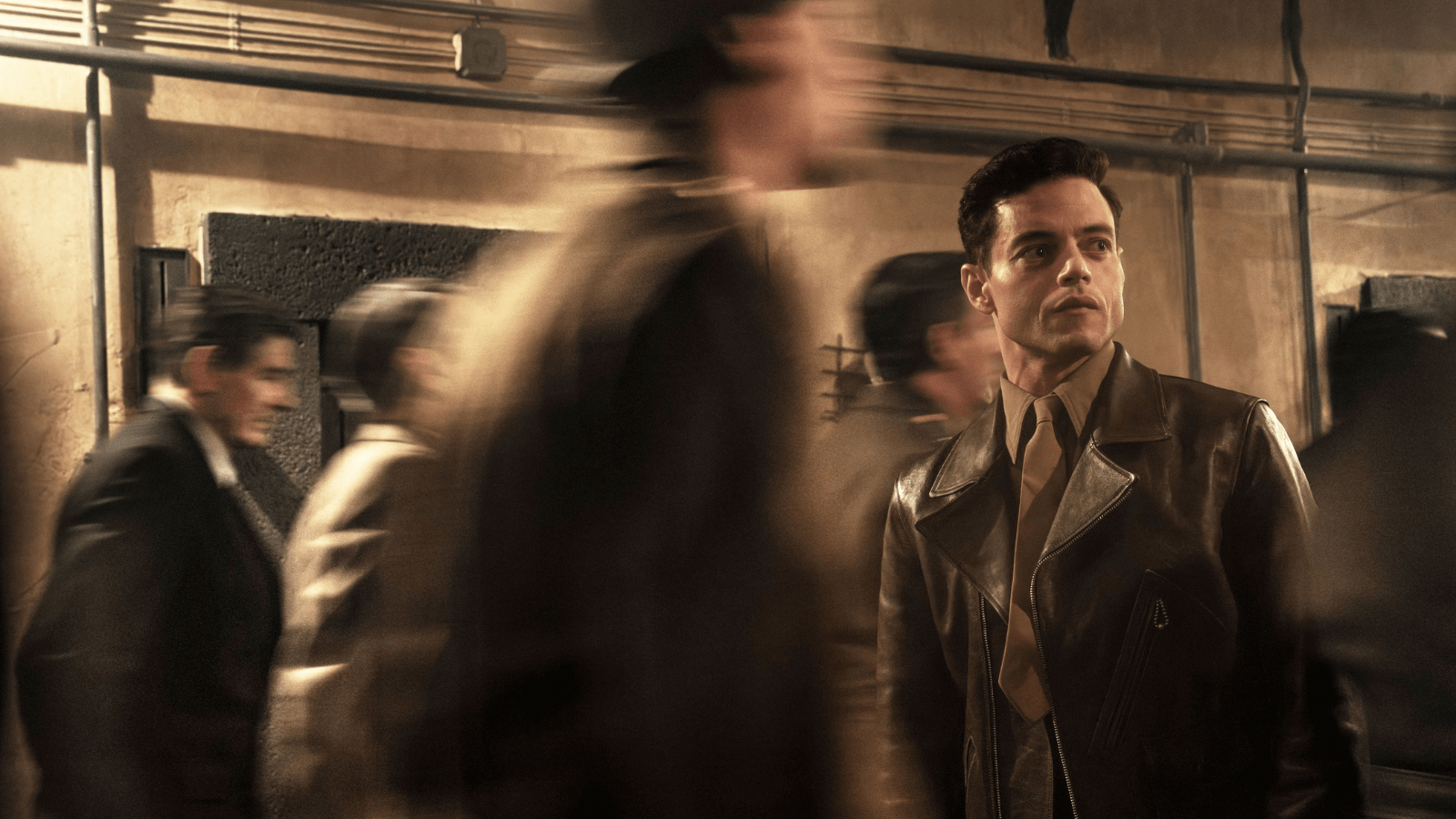

“What if we could dissect evil?” That’s the question posed by Douglas Kelley, played by Rami Malek in Nuremberg. An ambitious psychiatrist, Kelley is tasked with assessing the mental state of Hermann Göring (Russell Crowe) while the former Reichsmarschall awaits trial. World War II has just ended. Adolf Hitler has killed himself. The chief U.S. prosecutor, Robert H. Jackson (Michael Shannon), a Supreme Court Justice, argues against a swift execution of the Nazi high command for the atrocities they planned and oversaw. Jackson wants them judged by international law—four international judges from Allied forces sitting on an unprecedented tribunal: the first courtroom trial to confront Nazi Germany’s invasions of other European countries and genocide against millions of Jewish people. Before what would be known as the Nuremberg Trials, Kelley must try to understand Göring. He learns less about the origin of evil than about humans having the capacity to do unthinkably awful things and then justify those actions through a warped worldview.

Hannah Arendt coined the phrase “the banality of evil” about such cases. And just as 2023’s The Zone of Interest depicted, Nuremberg captures how the Holocaust was not carried out by some supernatural evil but by everyday people so entrenched in their beliefs, ambition, and power that they committed horrific acts against their fellow human beings. Based on Jack El-Hai’s 2013 book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist, writer-director James Vanderbilt’s film has disturbing modern-day parallels. It’s also a stately production, presented in a classical mode that’s sure to appeal to old-school Oscar voters. However, a similar theme appeared in last year’s superior Norwegian feature, Quisling: The Final Days, where a priest (Anders Danielsen Lie) interviews Vidkun Quisling (Gard B. Eidsvold), the leader of Norway’s puppet government for Hitler. Both that film and Nuremberg follow the same trajectory, and while I prefer the former, there’s much to appreciate about Vanderbilt’s effort here.

Whereas Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) spent over three hours on the subject, with much of its runtime situated in the courtroom, Vanderbilt devotes most of his story to Kelley’s pre-trial assessment of Göring. Kelley wants to explore what drives the Nazis’ brand of evil to write a book about it, earn a hefty payday, and ensure something like the Holocaust never happens again. However, Kelley has an ironic mission similar to Burton C. Andrus (John Slattery), the U.S. Army colonel who oversees the 22 prisoners awaiting their trial: he must keep the Nazis alive long enough to face their inevitable execution. When Kelley first meets Göring, he observes the man’s unabashed narcissism, failing health, and addiction to opiates stemming from wartime injuries. There’s a cat-and-mouse quality initially, where Kelley attempts to outwit Göring, who speaks English but pretends he cannot to earn a tactical advantage. Göring remains certain he will escape conviction and the hangman’s noose.

Meanwhile, Jackson works out the legal logistics of trying this case alongside other prosecutors from England, Russia, and France—chief among them, the British representative, David Maxwell Fyfe (Richard E. Grant). Jackson also needs the support of the Pope, who ostensibly validated Hitler’s reign in 1933. The actual trial doesn’t begin until nearly two hours into the feature, leaving Jackson’s ten-minute cross-examination of Göring for the climactic scene. Until then, Kelley tries to understand Göring by meeting his wife and children and listening to Göring’s assessment of how Hitler “made us feel German again” and promised to help “reclaim our former glory.” Göring also claims ignorance about what happened at the concentration camps, insisting that Heinrich Himmler oversaw them. His “not my department” explanation falls through later, and Kelley loses any respect he might’ve gained from Göring when Jackson shows the court nightmarish footage of the death camps and the scope of genocide. How could he not have known?

Much of Nuremberg’s heavy dramatic lifting falls on Malek and Crowe, who handle their scenes well—although Crowe’s iffy German accent sounds vaguely similar to his Italian accent in The Pope’s Exorcist (2023). Vanderbilt’s production allows for plenty of showboating among the cast, whose performances are reinforced by Brian Tyler’s heightened score. Dariusz Wolski’s cinematography, captured in a brown-gray palette, doesn’t dwell on the courtroom stage as much as the faces of those involved, mainly in medium and close-up shots. Vanderbilt and editor Tom Eagles also weave in archival footage and several sobering minutes of actual footage from concentration camps shown in the courtroom. The effect is that neither Göring nor any of Hitler’s cronies could claim ignorance or that they were “just following orders.” The Third Reich could not have executed the level of planning and coordination required for its Final Solution without the knowledge and participation of its leaders.

A movie like Nuremberg, wrapped in the prestigious airs of an Oscar-baity production, may not offer a new take on the trials. But watching it, I kept thinking about how some kid might find the movie on Netflix and learn about humanity’s dark past, and perhaps even draw some parallels to today. That’s something. A survey by the Claims Conference shows that awareness and knowledge about the Holocaust among young adults in the United States are severely lacking. While the Trump administration purges information about the Holocaust from government websites, removes related books from national libraries, and narrows the scope of Holocaust education in American schools, Vanderbilt’s work helps raise awareness and emphasize the contemporary parallels. In the final scenes, Kelley has become a disenchanted alcoholic because “people let it happen.” His faith in humanity irreparably damaged, he warns that fascism can and does exist in America, and that another Holocaust could happen here. Everyone thinks he’s a crackpot, and his warnings go unheeded. Today, his claims wouldn’t sound so implausible; they’d be stating the obvious.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review