Jurassic World Rebirth

By Brian Eggert |

Jurassic World Rebirth further proves that Steven Spielberg invented the visual language of modern blockbusters, and other filmmakers merely speak in it. Rather than create something new, director Gareth Edwards spends 134 minutes paying homage to Spielberg and his 1993 original, Jurassic Park. But more than just the masterful first film based on Michael Crichton’s book, or even its now-six sequels, Edwards also nods to Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) in a recapitulation of iconic Hollywood imagery. No slouch himself, Edwards—the helmer of Monsters (2010), Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016), and The Creator (2023)—devises almost nothing new here. What seems new stems from recycled ideas that never really worked in the first place, such as genetically altered mutant dinosaurs. Rather than take the time to stretch his talent, Edwards falls back on the same reverence for Spielberg that directors Colin Trevorrow and J.A. Bayona displayed in Jurassic World (2015), Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (2018), and Jurassic World Dominion (2022). And yet, even though Edwards’ visual nods to Spielberg and Rebirth‘s story autocannibalize the Jurassic series, it manages to be more purely entertaining than the last two installments.

Ironically, the subtextual theme of Jurassic Park questions the motivations of blockbuster filmmaking, with the original park’s mastermind, John Hammond, nothing more than a flea circus manager whose attractions got bigger and more expensive. Hammond served as an onscreen counterpart to Spielberg, who interrogated his contributions to a medium he loved in hopes of being taken seriously as an artist (which he achieved with Schindler’s List, released the same year as Jurassic Park). However, there’s nothing so introspective about the sequels. But in another ironic turn, all four Jurassic World movies critique corporate greed for making the same mistakes all over again, even as they become the very thing they critique. Their shared theme about the importance of preserving human and animal life, while condemning those who place greed above all else—an idea borrowed from Jurassic Park, which repurposed it from Jaws—tends to fall flat. This is especially true as each sequel exploits the same premise and reuses memorable imagery crafted by Spielberg because the filmmakers are bereft of new ideas.

Rebirth at least benefits from David Koepp as its screenwriter, who returns to the franchise after penning the original and The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997). Koepp’s recent screenplays have questioned corporations that exploit and diminish the value of human lives in the spirit of capitalism, and his scripts for Kimi (2020), Presence (2025), Black Bag (2025), and others feel attuned to this moment in American history. With Rebirth, his characters debate what’s more important: helping people with open-source science or getting a fat payday. In a plot worthy of a video game, ParkerGenix, a pharmaceutical company, needs blood samples from the three largest living dinosaurs to create a medicine that will eliminate heart disease. Company suit Martin Krebs (Rupert Friend) enlists the help of Zora (Scarlett Johansson), a specialist in “situational security and reaction,” who agrees to put a team together for $10 million, head to a forbidden dinosaur island, and acquire the necessary blood samples.

But before any of that happens, Rebirth opens by teasing the resident Big Bad: 17 years ago, inside an InGen research facility that experiments with splicing dinosaur DNA for new and more horrifying theme park attractions, a security malfunction—as maddeningly trivial as the Tuttle-Buttle debacle in Brazil (1985)—leads to a freakish dino-monster escaping. As we will see later, the thing looks like a silly combination of a T-rex, a xenomorph from Alien (1979), and a Rancor Pit monster from Star Wars: Episode IV – Return of the Jedi (1983). Why must the Jurassic and Alien franchises mutate their monsters when the original proved scary enough? As one sequence in Rebirth reminds us, the T-rex doesn’t need to be genetically modified to deliver thrills. Regardless, the movie picks up five years after the events in Dominion, in the so-called Neo-Jurassic Age. The escaped dinosaurs of earlier Jurassic World movies have mostly died out, save for those thriving on a few off-limits islands around the equator. Zora’s team, including paleontologist Dr. Loomis (Jonathan Bailey) and fellow mercenary Duncan Kincaid (Mahershala Ali), must visit the mutant dinosaur island to get their samples.

“No one’s dumb enough to go where we’re going,” remarks Kincaid, whose crew includes a few nondescript members doomed to become lunch. Koepp’s script contains some flat scenes of boilerplate backstory shaped by trauma, establishing minor dramatic arcs for Zora, Kincaid, and Loomis—all elevated by the actors’ star power. Grappling with PTSD since her last mission, Zora has grown tired of her dangerous profession and wants to retire after this One Last Job. Kincaid was recently divorced after losing a child, and he hopes to redeem himself somehow. Loomis wants people to appreciate the majesty of dinosaurs and frets that “Nobody cares about these animals anymore.” He also doesn’t trust ParkerGenix, who will surely make their miracle heart drug exclusive to the superrich. There’s also the Delgado family, headed by Reuben (Manuel Garcia-Rulfo). Along with his teenage daughter Teresa (Luna Blaise), his youngest Bella (Audrina Miranda, excellent), and Teresa’s boyfriend Xavier (David Iacono), Reuben sails on a small boat across the Atlantic—a bad idea when there are dinosaurs in the water. The Delgados soon need rescuing by the ParkerGenix team, who bring the family along on their mission to mutant dinosaur island. And almost immediately, the group’s well-laid plans fall apart. When has anything ever gone according to plan when it comes to the Jurassic dinosaurs?

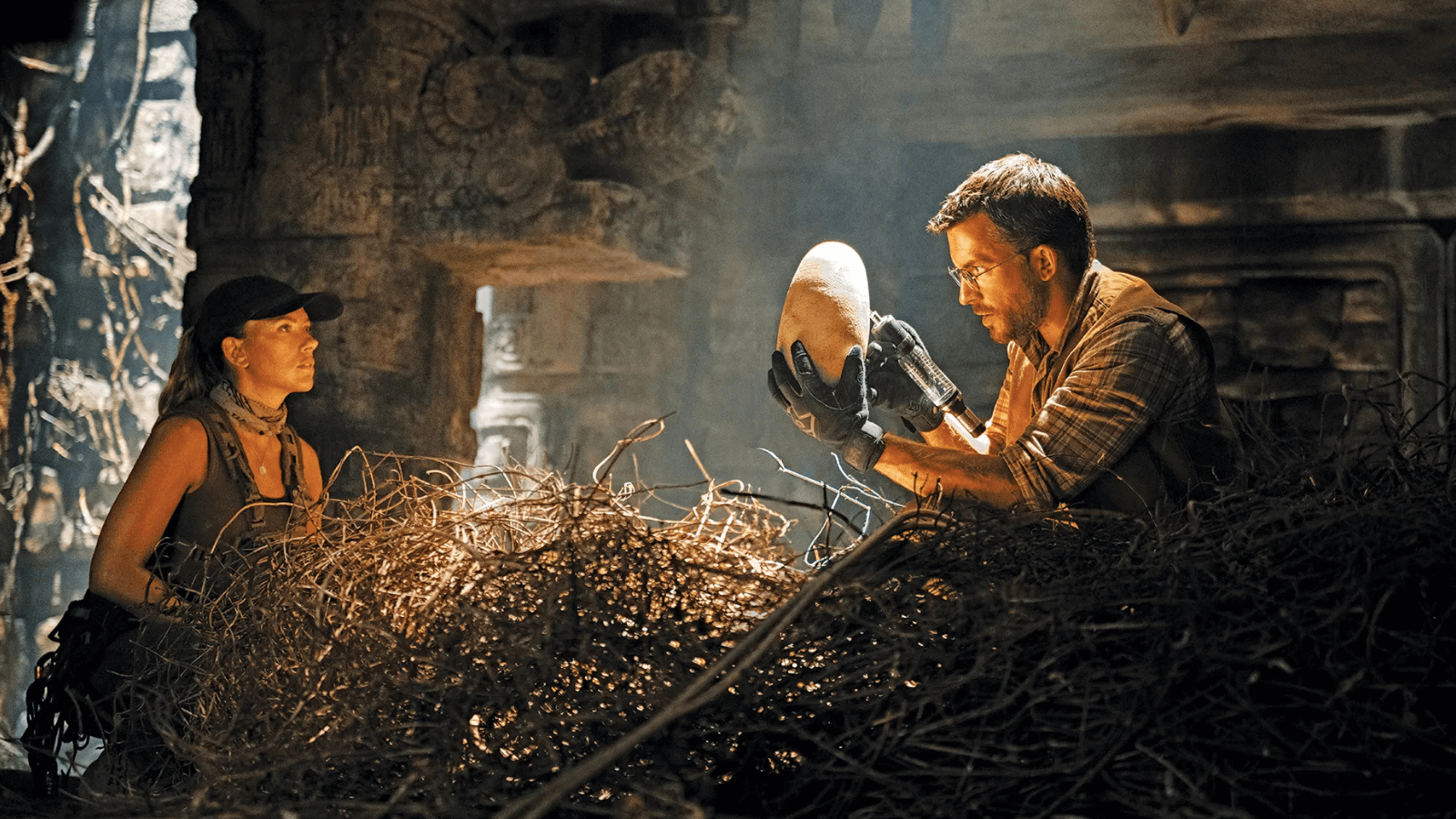

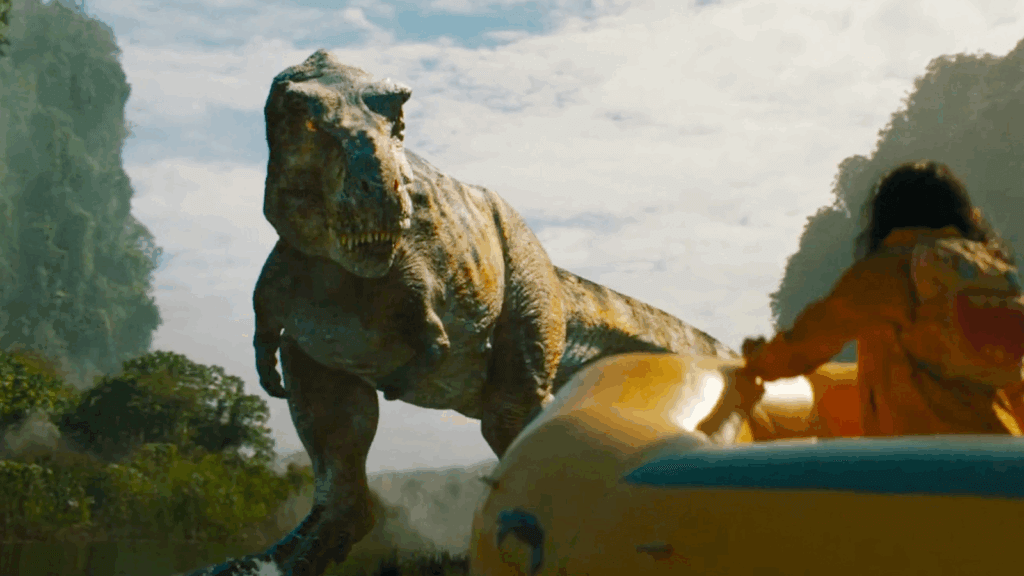

Edwards and cinematographer John Mathieson don’t waste any time before making Spielbergian visual references, from a falling “When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth” banner to a lingering shot of a car’s side-view mirror. Rebirth features one set piece after another that entirely replicates or draws from Spielbergian visual language, such as when a Mosasaurus attacks Kincaid’s boat in a sequence borrowed from Jaws. An awe-inspiring herd of Titanosaurs duplicates the majesty of the Brachiosaurus from the original film, complete with Alexandre Desplat’s score sampling John Williams’ unforgettable theme. In another scene, Edwards recreates the original film’s T-rex attack on the tour car, except with Bella hiding under an overturned river raft—a fantastic sequence, despite its derivativeness. And I dare you to watch when Dr. Loomis enters an ancient tomb to find the nest of a flying Quetzalcoatlus, where he holds a dinosaur egg like an ancient treasure, and not think of the near-identical shot in every Indiana Jones movie. The thing is, Edwards replicates these moments so well that they still deliver even as one notices where they originated.

Despite its secondhand visuals, Rebirth also features a few memorable, somewhat original scenes. At one point, Teresa, her family separated from the ParkerGenix crew, must quietly drag an inflatable raft across a dock toward a river without waking a nearby T-rex. The sleeping giant rolls over like a snoozing dog, snoring lightly until it wakes in a dread-filled moment. The ensuing chase down the river is delightfully squirm-inducing. I also enjoyed Bella’s affection for a cute little dinosaur she names Dolores and adopts as a pet. Plushies of the Aquilops will surely sell thousands of units at Universal Studios. And speaking of conspicuous marketing, the film’s Altoids, M&Ms, Snickers, and Dr. Pepper’s product placements prove distracting. When the survivors finally face the Big Bad, it’s an underwhelming encounter undone by the absurd-looking creature. It’s a far cry from the fearsome Indominus rex established in Jurassic World—the only worthwhile dino-hybrid in the franchise because of its warped, antisocial psychology.

Although many of its biggest moments draw from Spielberg’s filmography, Rebirth’s strong casting boosts its bland characters, just as Edwards’ cohesive filmmaking distracts from his lack of originality, and Koepp’s sufficient script supplies the intended popcorn-munching escapism. It’s far more enjoyable and self-contained—and decidedly less convoluted—than Fallen Kingdom or Dominion. Though the movie runs over two hours, it held my attention. But the material crumbles under scrutiny and doesn’t reward even a cursory examination. While Jurassic Park and even Jurassic World had enough self-awareness to craft films that questioned the hollowness of blockbusters, even while delivering expert blockbuster entertainment, Rebirth doesn’t have anything so reflective on its mind. Still, based on the applause and enthusiastic chatter from viewers after my preview screening, I suspect general audiences will enjoy this more than critics, who will undoubtedly take issue with Edwards’ cloning of Spielberg’s imagery and the overwhelming sense of déjà vu.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review