Materialists

By Brian Eggert |

A treatise on the perils and metrics of modern dating, Materialists explores how apps and matchmaking services reduce people to an objectifying checklist of preferred and non-negotiable characteristics. It is the second film by Celine Song, whose masterful debut Past Lives (2023) contained a layered look at a love triangle—not quite equilateral but more scalene in shape. Her sophomore effort features another love triangle, this one more of the isosceles variety. The theme seems to be an obsession shared by Song and her husband, Justin Kuritzkes, whose original screenplay for last year’s Challengers also dealt with an unconventional and competitive trio. Returning to the idea, Song has gone the commercial route and cast three heartthrobs in her film, placing star Dakota Johnson between Chris Evans and Pedro Pascal on the poster. Many won’t be able to resist. But rather than the lighthearted rom-com that distributor A24 has advertised, the film has much on its mind: the risks of dating, the reciprocal aspects of marriage, the superficiality of customizing your next date like Dr. Frankenstein, and the impact of finances on a relationship. Oh, and let’s not forget love.

Song’s screenplay nods to Jane Austen’s Emma and Persuasion and, most obviously, the transactional nature of marriage in Austen’s books. Johnson plays Lucy, the modern-day equivalent of Austen’s protagonists Emma Woodhouse and Anne Elliot. Much like Emma, Lucy is a matchmaker, albeit servicing New York City’s upper-class clientele who pay her agency, Adore, thousands of dollars to be paired with a “good match.” Lucy attempts to find a qualifying candidate by looking at each client’s demographics—income, height, weight, hair color, physical type, likes, dislikes, and politics. She sets up the date, and, hopefully, sparks fly. Early in the film, she earns praise from her enthused coworkers for introducing a couple who are now getting married. She’s responsible for nine marriages, each based on her clients’ checklists for their perfect mate. But like Emma, Lucy doesn’t know what she wants. Worse, her ability to spot a perfect match results in at least one disaster, and the consequences lead to a devastating turn.

Lucy also resembles Anne Elliot in that both were in relationships years ago, which have since ended, mainly due to economic concerns, and both consider whether breaking up with their ex was the right choice. Lucy once dated John (Evans), a struggling theater actor she loved, but he couldn’t afford the luxuries she wanted, drove a rickety jalopy, and now works part-time for a caterer. When the film opens, Lucy finds herself courted by someone who, in the dating “market” where she works, is considered a “unicorn.” Harry (Pascal) is wealthy, attractive, over six feet tall, and has good taste. “Ten out of ten,” she tells him. He’s out of her league according to her standards, which are defined by her shallow industry. Yet, he’s drawn to her. She has the chance to get everything she ever wanted—or thought she wanted—except she’s not quite over John. And that’s despite Harry being a perfect guy. He’s considerate, generous, and even has a vulnerability beneath the surface. He does, however, work in private equity—a reveal that earned groans in my screening, but Song doesn’t treat it as a drawback. (Let’s face it, he’s probably a ruthless monster at the office.)

Song draws from experience, having worked as a matchmaker while building a career as a playwright in New York. Her observations and scenario play out predictably enough for Austenites, but it’s not just Austen’s literature that captured these universal concerns. The film’s remarks on romance and marriage are timeless, which Song illustrates with a dreamy opening set in prehistoric times, where a caveman courts a cavewoman with an offering of stone tools and flowers. Cultures around the world support arranged marriages and couplings negotiated like a business deal. However, Song reminds her audience that people are capable of hiding their flaws and predatory behaviors in a subplot about Sophie (Zoë Winters), one of Lucy’s clients who has struggled to find a match. Sophie’s latest date results in a traumatic assault, which Lucy’s boss (Marin Ireland) reveals is a “known risk.” The incident reminds Lucy that finding a partner is more than the “math” aligning.

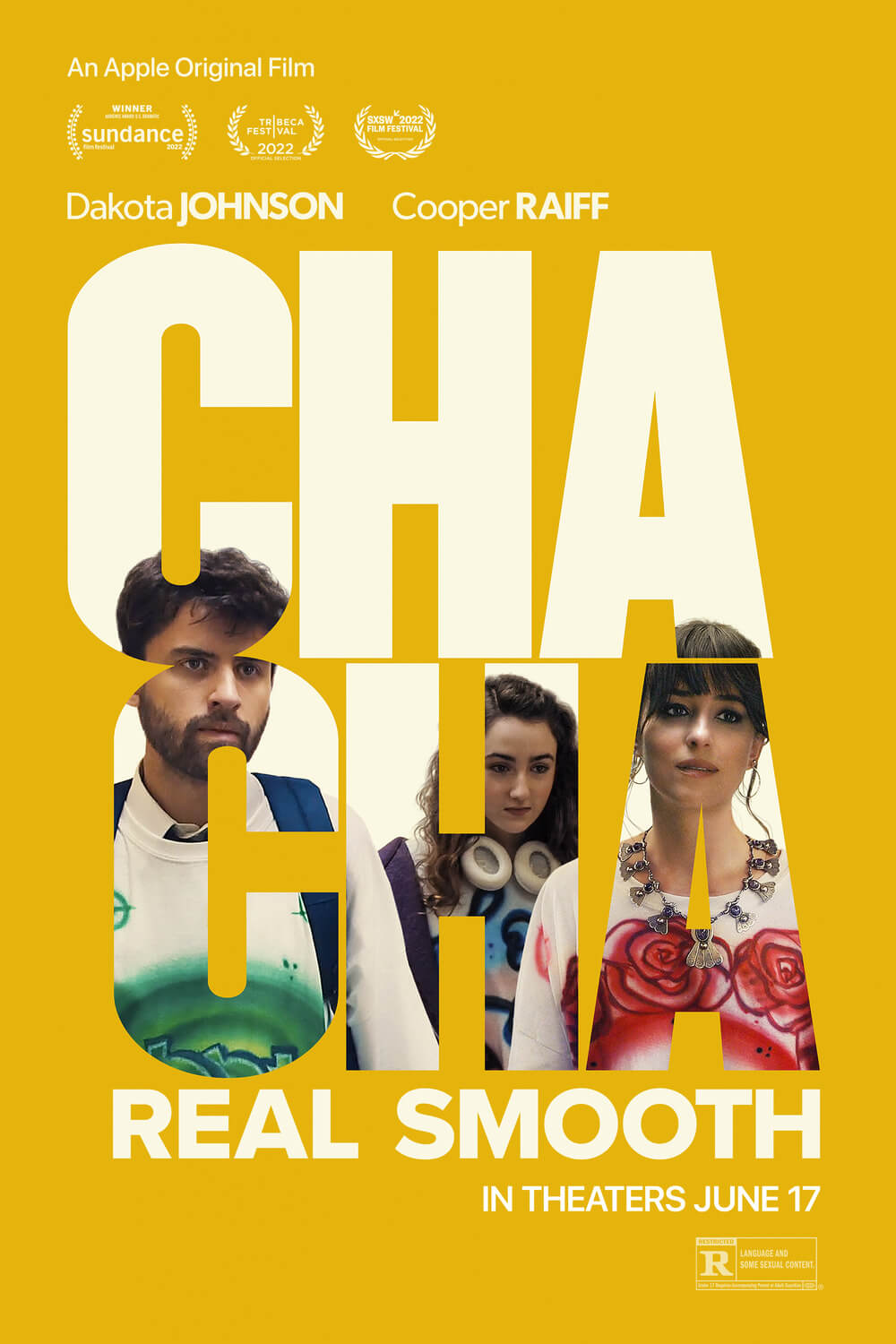

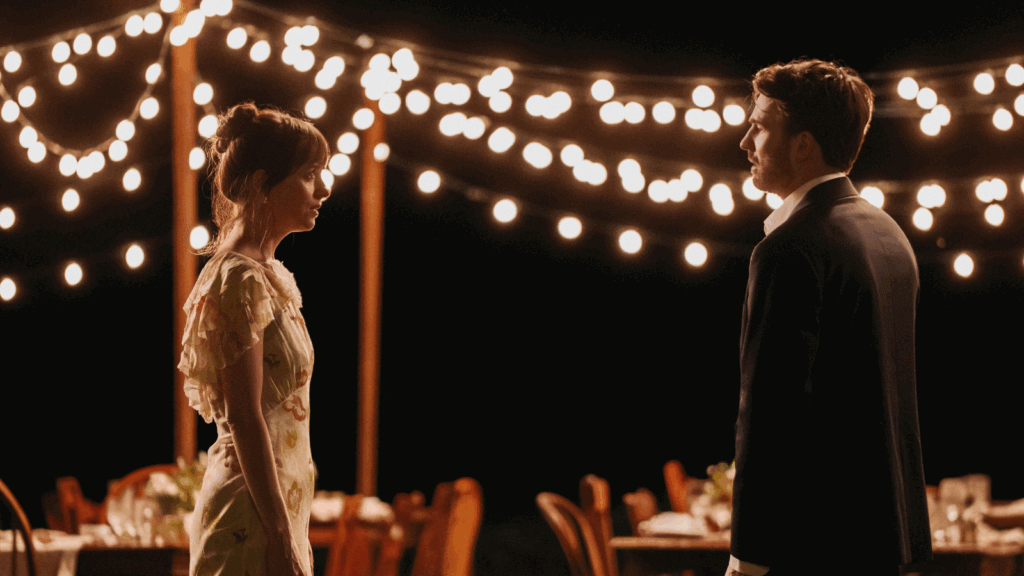

Materialists is a handsome-looking film, shot by Song’s Past Lives cinematographer Shabier Kirchner, who creates textured images that resist the overly bright and plain aesthetic of most romantic comedies today. Although Song once again packs her work with intelligence and emotion to emphasize that love is a serious business, her themes and narrative don’t harmonize as they did in Past Lives. Materialists doesn’t feel as focused and, especially in the last 20 minutes or so, Song and editor Keith Fraase wrap up the story in a series of disjointed scenes. However, her swoon-worthy cast makes the experience go down smoothly. Johnson is best in this kind of indie romance, as evidenced in Cha Cha Real Smooth (2022). The same is true of Evans, whose roles in megabudget commercial fare have overshadowed how charming he can be as a romantic lead in, say, The Nanny Diaries (2007). Similarly, Pascal hasn’t played a character like Harry before, but he has natural charisma that has made him a marquee name, suggesting he could—and should—be in more romances of this ilk.

Materialists’ familiar, even formulaic setup shouldn’t distract from Song’s universal, discerning questions about dating, relationships, and love. After all, artists keep returning to them because they’re ageless. The romance genre might seem trivial to some—like John, who remarks, “It’s just dating. It’s not that serious.” But, as Lucy argues, it’s not just “girl shit.” For many, the search for an ideal partner remains ongoing. Song thoughtfully explores how people preach about the purity of love, but then they deny themselves love based on their materialist needs or superficial desires. What’s curious about Materialists is that she still seems to believe in marriage even after cutting into and exposing its more contractual facets. In the film’s protracted ending, which stumbles and loses some narrative momentum, she stresses that marriage works best when it’s between two people in love. Sure, marriage can work in a transactional mode for some people, but one suspects that prenuptial contracts and financial considerations might obstruct passion. For others, love—not any of the other fleeting provisions or clauses negotiated beforehand—is what matters most. Go figure.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review