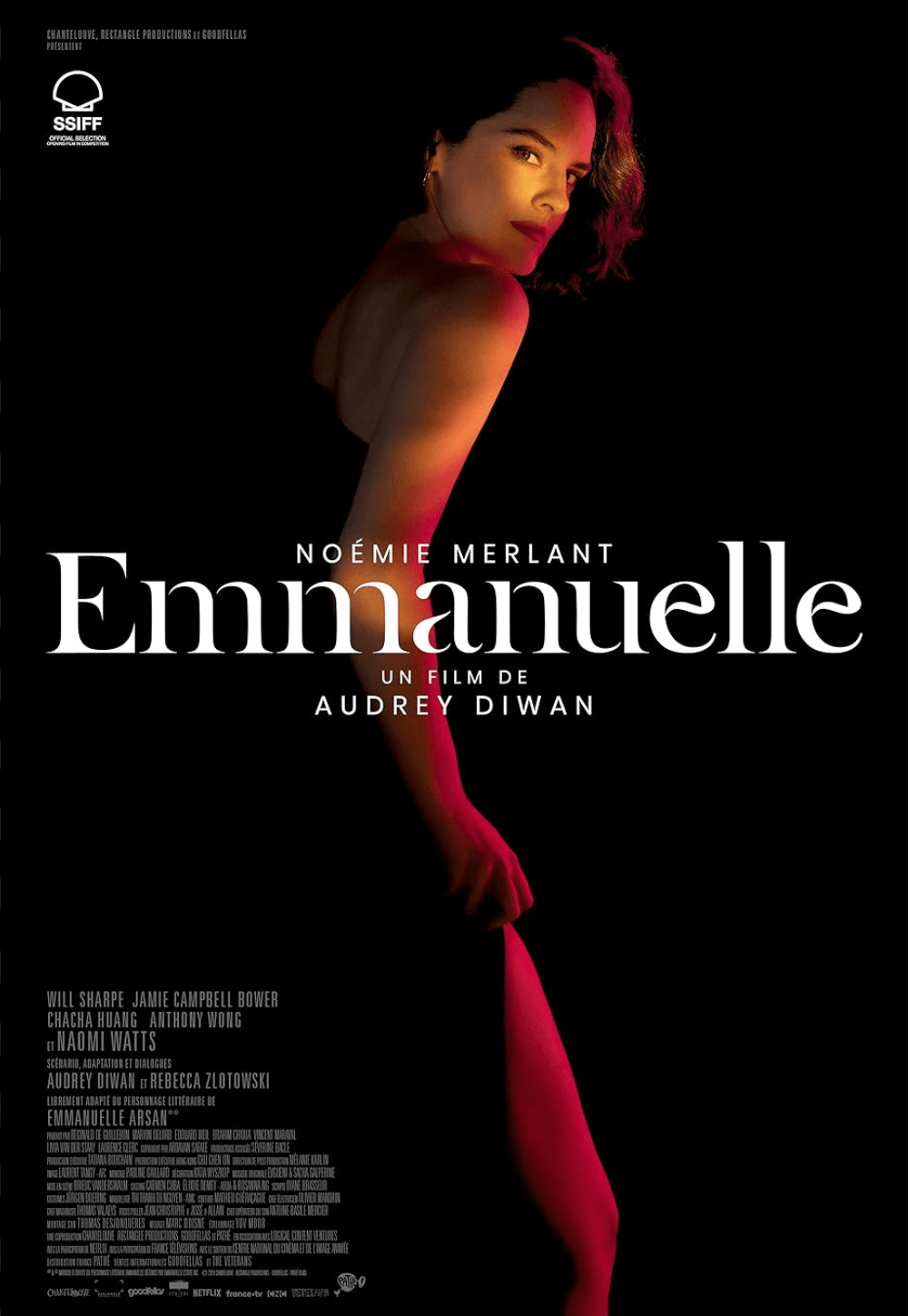

Emmanuelle

By Brian Eggert |

Note: After debuting at the San Sebastián International Film Festival in 2024, Emmanuelle is now available on VOD from Decal.

Emmanuelle is about searching for desire from within. Its protagonist, played by Noémie Merlant (Portrait of a Lady on Fire, 2019), engages in anonymous sex with strangers, hoping to feel something. Take the opening scene on an upscale flight to Hong Kong, initially shot from the perspective of another passenger: a voyeur across the aisle. He looks at her knees, framed by the thin black dress resting on her thighs, and watches her spread balm on her lips with her finger. Then she removes her cardigan, revealing shoulders only covered by a narrow strap. Having piqued his interest, she casually stands up and walks to the plane’s spacious restroom, lingering with the door open just long enough so that he knows to follow. Inside, their encounter is a passionless fuck. He finishes quickly. Her empty expression afterward suggests she felt nothing; it’s a meaningless act that failed to stimulate her. The film unfolds in this way, with Merlant’s character exploring her sexuality without passion or much genuine pleasure until, finally, she isolates her elusive desire.

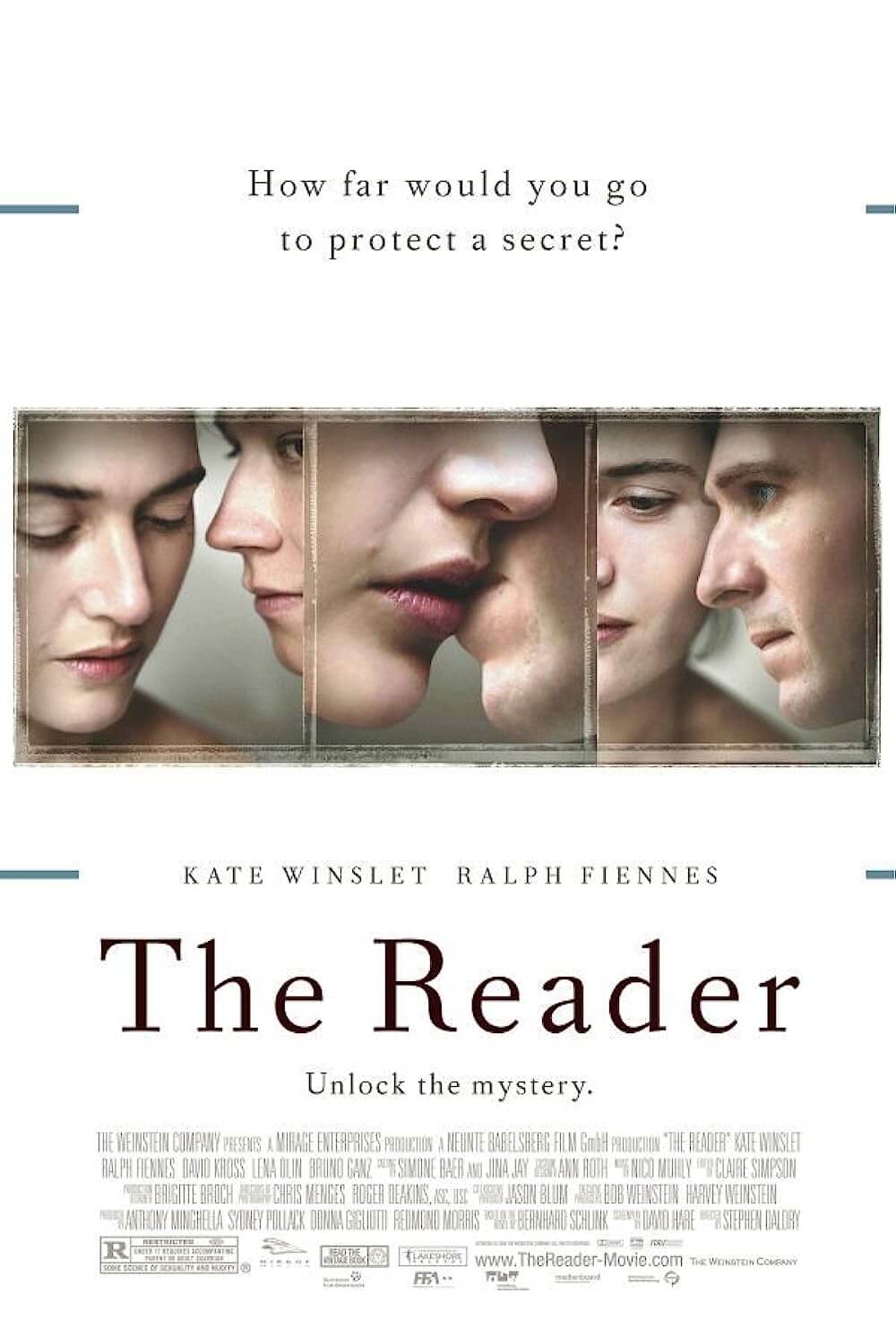

Director Audrey Diwan follows her masterful 2022 feature Happening, a drama about a college student who struggles to get an abortion in 1963 France, by looking at a much different aspect of womanhood. Diwan and co-writer Rebecca Zlotowski loosely based their screenplay on the 1967 book by Marayat Bibidh, a Thai-French author who went by the pen name Emmanuelle Arsan. The original text had been passed around as a salacious must-read in the years before its official publication, and afterward, its adaptation into a 1974 film—and the increasingly tawdry series of sequels and offshoots that followed—linked the name Emmanuelle with sexploitation. Diwan has something more thoughtful in store with her version, setting aside the author’s Bangkok-set narrative about a married 19-year-old’s sexual awakening. The new version of Emmanuelle keeps the audience at a distance, avoiding outright eroticism for much of the story until a few key incidents in which the titular character achieves some long-sought measure of self-understanding.

That distance, coupled with Diwan’s treatment of Emmanuelle’s searching, kept many critics at a remove. Some complained it wasn’t “tender or perverse enough” or that “the audience isn’t experiencing any more pleasure than the characters on screen.” Others labeled it “pedestrian” or simply “inert.” Without resorting to generalizations, some of the critical panning seemed to want a sexier, more openly transgressive experience with a clearer message. But that’s not the film Diwan has made, and it’s not out of incompetence. Diwan did not intend Emmanuelle to be alluring, and so she didn’t fail in her execution. Rather, if Diwan and Merlant’s interpretation of the material and its central character seem steely, hollow, or challenging to interpret, that’s by design. Sexuality is far from simple. It can take years for people to understand their tastes and access what pleases them. Diwan understands that and dramatizes the journey. As a result, many of Emmanuelle’s experiences register as unfulfilling and dispassionate—until they don’t.

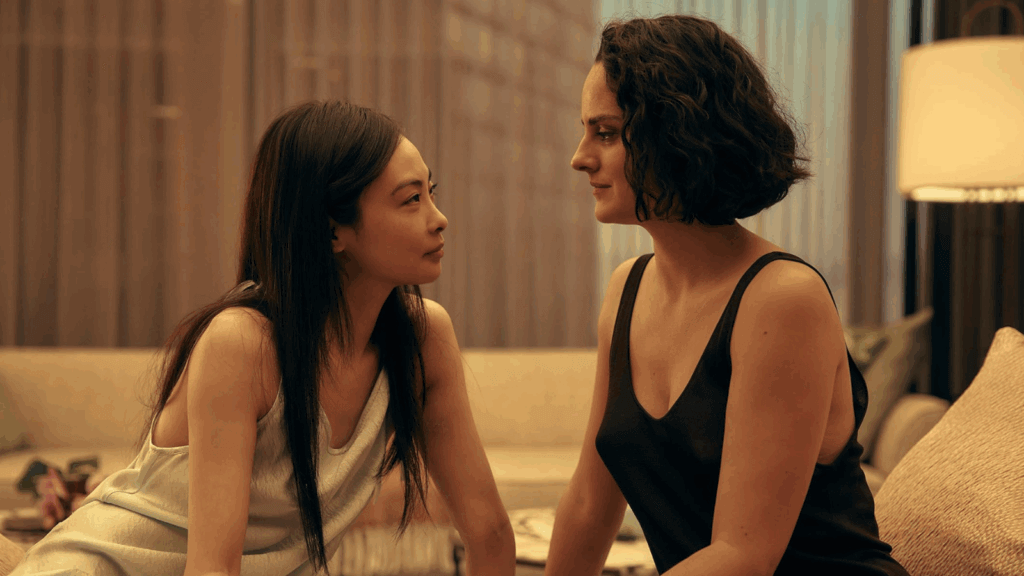

In the new version, the protagonist works as a quality control auditor for a luxury hotel company. Her latest assignment brings her to Hong Kong’s Rosefield Palace, an opulent, stunning backdrop worthy of The White Lotus. She’s tasked with finding something wrong about how the manager, Margot (Naomi Watts), runs the hotel, and the staff knows what to expect: Emmanuelle remains critical, unimpressed, and unmoved by their service and extravagances. Even as they dote, she seems to enjoy nothing—an apt parallel to her sex life. Between assessing how well management knows the clientele and timing the order of her drink delivery by the pool, she also sleeps with hotel guests, almost exclusively composed of wealthy, attractive people. “This kind of behavior is tolerated but not allowed,” she explains. Her encounters range from a threesome with a couple she meets at the bar to a prolonged association with a sexworker, Zelda (Chacha Huang), whose interest in being watched and seen ignites something in Emmanuelle. She and Zelda masturbate while watching each other, and that distanced connection is alluring for Emmanuelle—at once with someone yet achieving pleasure from herself. It’s fitting that Zelda sizes her up better than anyone else, recognizing that she, too, comes from a modest background and cannot shake her roots.

Soon, Emmanuelle focuses on a mysterious hotel guest named Kei (Will Sharpe), who, early on, notices her in-flight fling from his seat on the same plane to Hong Kong. Kei is a mystery to her, partly because not even the hotel’s resourceful staff knows who he is or what he does, and partly because he doesn’t seem interested in her sexually. She attempts to draw him into a sudden tryst, but as he explains later, he has “run out of desire”—he takes no joy from food or sleep, and for a living, he builds dams despite knowing rising sea levels will overcome them. In these scenes, Sharpe’s acting can register as a little stilted, and his American accent is flat, but perhaps that’s a choice to convey his despondency. Still, their conversations show Emmanuelle intrigued, even eager, to find a way to seduce Kei. As she sneaks into his room to bathe in his tub or takes photos of herself in a provocative outfit, Merlant’s restrained but many-layered performance shows her character engaged, unlike her physical experiences with others. It’s less about bringing Kei pleasure or even desire, since he’s shut off from those feelings, than enjoying the process of creating a desire within herself for herself, which brings her pleasure.

To watch Emmanuelle is to see a film that doesn’t conform to the audience’s expectations, which may account for the mostly negative responses. Diwan has unmistakable control of her craft. Her images have a moody, rich lighting that captures the hotel’s grandeur. Her sex scenes occur without a male-gazey perspective, and some without a voyeuristic eye. Diwan is conscious of where she and cinematographer Laurent Tangy point the camera; their compositions are tasteful and never feel exploitative. She prefers dwelling on faces instead of bodies, knowing facial expressions are where the action happens. Adding to the effect, the filmmaker turns up voices and breathing in the audio mix, which should please the ASMR crowd. Diwan doesn’t shoot mere sex; she shoots desire or the absence thereof. This requires the audience to differentiate between moments when Emmanuelle feels detached and others when she experiences pleasure.

So much sexual representation follows the cultural routine designed to appease heterosexual male desire and fulfillment. Emmanuelle begins the story caught in that patriarchal dynamic, drawing others, primarily men, into experiences she finds unsatisfying. Zelda shows her an alternative when they’re together in a setting that might get them caught. But the real revelation is when she finds desire within herself. Posh amenities and extravagance surround her; however, Zelda claims the only democratic, universal luxury available to everyone is “pleasure when I want it.” Emmanuelle has been searching elsewhere for that pleasure. “What exactly are you looking for?” Margot asks her at one point—a somewhat obvious, symbolic question. She is determined, even courageous, and arguably irresponsible in her pursuit, but the solution is literally in the mirror. The picture’s climax is not about bringing pleasure and desire to others but fulfilling herself by clearly communicating what she wants. “Do you like that?” becomes the most erotic phrase in the film.

Although the theme of uninhibited sexual exploration has been the subject of other films—see Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977), which is similar in that both initially depict women wrapped up in what men want—Emmanuelle proves more individualistic. This work of sex positivity recognizes that sexuality is a journey of trial and error, whether you’re experimenting with the same partner or many partners over a lifetime. Diwan warns against limiting desire and pleasure to standard modes, echoed by the predictable patterns and structure of the hotel and the well-established expectations of male desire. Rather, her film is about finding the unique rhythm that pleases you. Diwan reframes cinematic sensuality in a way that isn’t about the visual payoff but about identifying with a character whose search for pleasure leads her within. It isn’t what many will expect or even want from this material, and Diwan’s thoughtful, restrained, intentional work doesn’t make it easy for viewers. But it’s a perceptive film capable of prompting healthy introspection and conversation about sexuality.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review