Thunderbolts*

By Brian Eggert |

In the opening frames of Thunderbolts*, the Marvel Studios logo—usually awash in red and silver—appears shrouded in opaque black. Then Yelena, the former Russian assassin, vibrantly played by Florence Pugh, speaks: “There’s something wrong with me, an emptiness… a void.” Dispatched to Malaysia by her CIA handler and tasked with cleaning up a botched experiment, Yelena admits she’s “without purpose” and “drifting.” She’s haunted by the horrible things she did as a child in the same Soviet program that trained her late sister, Black Widow—not to mention the awful things she has done in the years since. Eventually, she’s faced with a living embodiment of her psychological state—a character with an all-consuming dark side whom she’s desperate to save. Indeed, here’s an entry in the Marvel Cinematic Universe that isn’t about saving the multiverse, the planet, or even a city from destruction. It’s about helping your friends deal with their destructive side and, by extension, the throes of bipolar disorder. That’s not just subtext or a theme; it’s part of the central narrative, making this the most human entry in the MCU and easily one of its best and most compelling offerings in recent years.

From the marketing campaign that underlines its A24-versed talent to the heartening underdog status of its main characters, Thunderbolts* announces itself as an antidote to superhero fatigue. But the more things change, the more they stay the same. Despite being populated by a group of “defective losers,” the titular team assembles—not unlike Earth’s mightiest heroes, the Avengers—to stop an unbeatable threat. While the story structure proves superficially familiar, what makes the movie unique among the increasingly homogenized entries of the MCU is its surprising humanity. The latest Marvel cinematic team consists of several misfits, former villains, and unstable newcomers, each trying to prove themselves despite their mistakes. And it’s not just that they’re scrappy antiheroes—they also enrich the movie’s commentary about depressive impulses; they grapple with guilt, shame, and regret; they face and overcome suicidal thoughts. Although decidedly heavy, it’s more rewarding than the usual MCU formula. Personally, I find it easier to root for someone with relatable mental health issues than a cocky billionaire, Norse god, or walking chunk of Americana.

Still, the asterisk in the title may be too bold in proclaiming the movie’s uniqueness in the superhero genre. A cynic might point out that the MCU already produced a team of outcasts and ex-baddies with James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy trilogy. Warner Bros., too, explored a similar concept with two loosely connected Suicide Squad features (the second directed by Gunn in 2021). With Gunn having departed the MCU to run the DC universe at Warner Bros., overseer Kevin Feige resolved to fly a new freak flag in his arena. The titular protagonists aren’t unstoppable superheroes who seem relatable because of their wisecracks and infighting. They’re fallible, antisocial, and almost-forgotten side characters from previous MCU movies and shows, whom some casual viewers may not even recognize. Moreover, their mere “punch and shoot” abilities limit their effectiveness, and their physical vulnerabilities are echoed by their psychological insecurities and troubled personal histories.

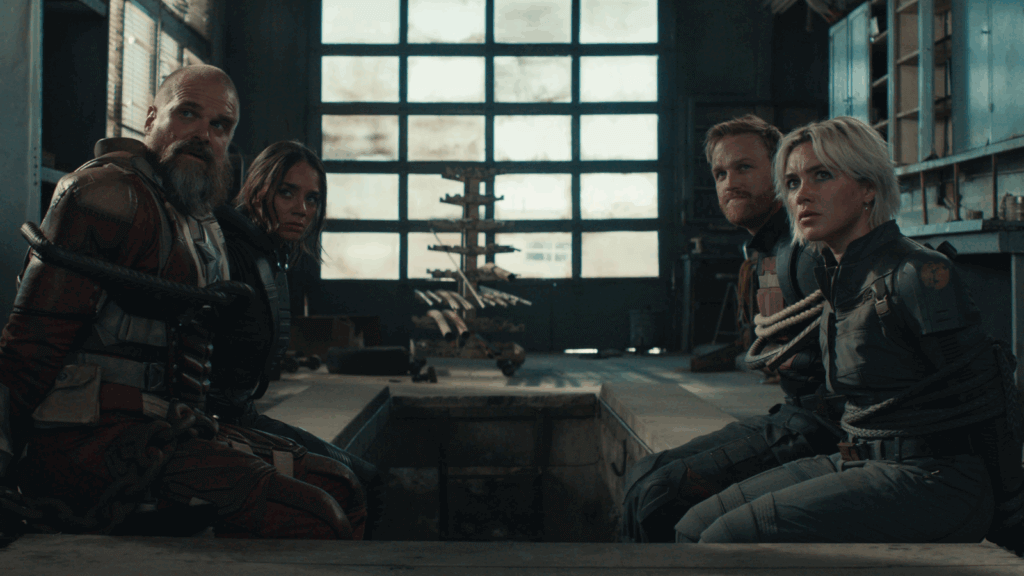

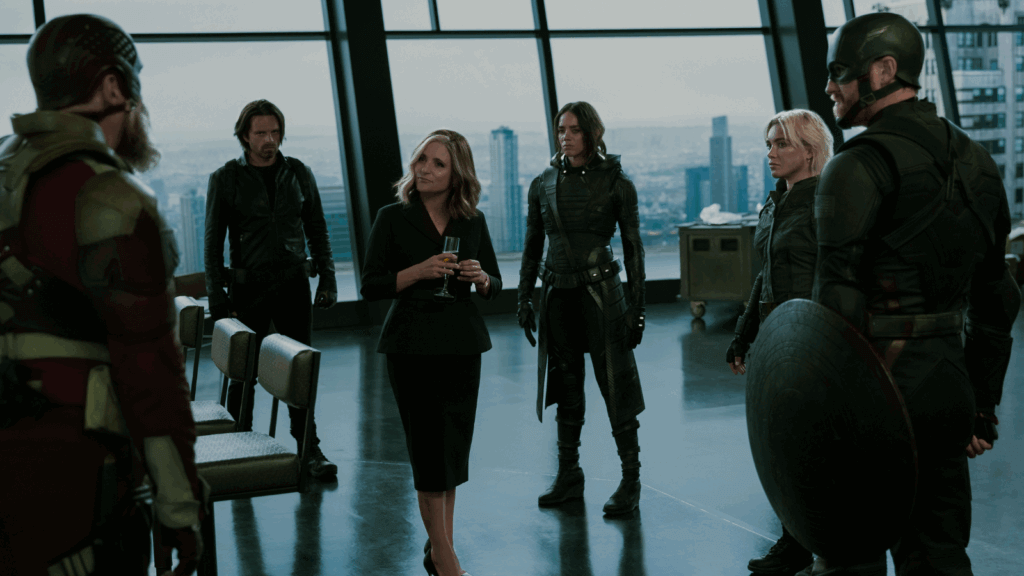

Take Yelena, who feels adrift working for CIA director Valentina Allegra de Fontaine (Julia Louis-Dreyfus), executing one mission after another. Yelena wants a more public role—to find fulfillment by helping others instead of numbing wet work. However, Valentina is facing impeachment for some shady schemes, so she plans to tie up all of her loose ends at once. Yelena finds herself targeted for termination along with Valentina’s other covert operatives. Among them is John Walker (Wyatt Russell), Steve Rogers’ would-be replacement as Captain America, who washed out because of his anger issues in the limited series The Falcon and the Winter Soldier (2021). There’s also Ghost (Hannah John-Kamen), last seen in Ant-Man and the Wasp (2018), who can phase through solid objects. The assassin Taskmaster (Olga Kurylenko) from Black Widow (2021) also appears. They’re later joined by Yelena’s brash and boisterous father, Red Guardian (David Harbour), the Soviet counterpart to Captain America. They’re also given some guidance by Bucky Barnes (Sebastian Stan), who has, for the moment, traded his Winter Soldier role for a seat in Congress.

Each of them questions whether they’re hero material, yet their self-hatred and doubt make them more complex than your usual superhero. How appropriate, then, that the newly christened team, its unofficial name taken from Yelena’s child soccer team, faces an imposing new foe defined by his duality—an inner conflict split between an aspirational hero and an uncontrollable villain. Enter Bob (Lewis Pullman), a former meth addict with a troubled past and a tendency for extreme highs and lows. He also happens to be the only survivor of Valentina’s attempt to engineer a superhero replacement for the now-absent Avengers. In a storyline reminiscent of Amazon Prime Video’s The Boys (2019-present), where the resident Superman, known as Homelander, also happens to be an egomaniacal head case, Bob becomes the all-powerful Sentry, whose shadow self emerges as a black-as-pitch entity. By this time, Yelena and company endear themselves to Bob and will risk everything to save him from himself.

Refreshingly, Thunderbolts* avoids certain aspects of the MCU’s so-called house style and stands apart thanks to the creatives behind the camera. That includes director Jake Schreier, whose feature film credits are less impressive than his various episodes of great television, such as Netflix’s Beef (2023) and the woefully underseen Minx (2022-2023). Cinematographer Andrew Droz Palermo, who has given two David Lowery projects their visual luster (see A Ghost Story, 2017 and The Green Knight, 2020), lends the visuals a texture, intimacy, and naturalness seldom found in the digital flatness of some MCU features. Even the score by avant-garde band Son Lux represents a welcome change from the typical generic background music accompanying MCU films. And while the production cannot avoid a CGI-heavy climax, it’s in service of our new heroes racing to save everyday citizens from falling debris and each other from “shame rooms” that reflect their inner pain.

The screenplay was written by longtime Marvel contributor Eric Pearson and MCU newcomer Joanna Calo, who has written for Beef, The Bear (2022-present), and most significantly, BoJack Horseman (2014-2020), one of the best shows ever made about depression. Calo seems like the secret weapon who made Thunderbolts* what it is. The script imbues these would-be superheroes with an emotional rawness that feels more genuine than the usual human conflicts that arise in superhero fare. It also inspires some terrific acting instead of overpaid celebrities coasting through their performances against a green screen backdrop. Pugh is wonderful and heartening as Yelena, who has already stolen the spotlight in Black Widow and the miniseries Hawkeye (2021). Few people can play their role’s emotional wounds as well as her. And while the entire cast has its moments, Pullman is excellent as Bob (also his amusingly plain name in 2022’s Top Gun: Maverick), lost and caught between two polar frames of mind.

Of course, these deviations from the typical Marvel playbook result from the franchise’s flailing desperation to find its groove in the postcoital dysphoria following Avengers: Endgame (2019). That’s six years of uneven and underwhelming MCU titles, which, apart from a few exceptions, have gotten lost in too many characters, too many supplementary shows on Disney+, and little overall direction. Thunderbolts* is just the latest of several movies that have tried to swing the series onto a new path, leading to the doubtlessly overstuffed crossover events with Avengers: Doomsday and Avengers: Secret Wars in 2026 and 2027, respectively. However, these impending event movies don’t have the same gravitational pull that Thanos and the Infinity Stones did, partly because they’re dependent on a disorderly multiverse setup that, by definition, scatters what was previously a clear, well, endgame. Occasional bright spots like Thunderbolts* remind us that, though the MCU’s heyday has passed and, as a whole, may be more fragmented than ever, there’s still potential for the occasional standout installment in the franchise.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review