Twin Cities Film Fest 2023 – Dispatch 2

By Brian Eggert | October 26, 2023

The Twin Cities Film Fest (TCFF) runs in a hybrid format from October 19 to October 28. Order tickets or buy a streaming pass on the TCFF website, or check out the in-person screenings at the ShowPlace ICON Theatre at the West End in St. Louis Park, MN. Some of the short reviews below may be expanded into full-length reviews to coincide with the film’s official release. In the meantime, here are my initial impressions.

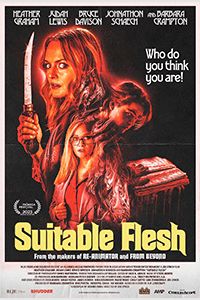

Suitable Flesh

Suitable Flesh

Maybe I let my expectations get the best of me with Suitable Flesh. Going in, I knew it was an adaptation of an H.P. Lovecraft story, told in the style of directors Brian De Palma (Carrie, 1976) and especially Stuart Gordon. The latter filmmaker is known for his splattery Lovecraft adaptations, including Re-Animator (1985) and From Beyond (1986), both featuring scream queen Barbara Crampton. Seeing Crampton’s name among the credits for Suitable Flesh piqued my interest, given my affinity for her work in the late, great Gordon’s cult output. The feature even originated with Gordon’s usual screenwriter, Dennis Paoli, a horror scribe and longtime collaborator with genre icons such as Brian Yuzna (Society, 1989). All of this creative talent conspired to fill me with anticipation. So, after a few minutes into the movie, when it became clear the filmmaking was clunky and the writing ham-fisted, I felt woefully disappointed.

Directed by Joe Lynch, the film has all the makings of a juicy helping of cosmic horror and psychosexual thrills. Heather Graham stars as Dr. Elizabeth Derby, a psychiatrist who becomes obsessed with a new patient, Asa (Judah Lewis). When Asa bursts into her office and claims someone is attempting to control his mind, she believes he’s experiencing a schizophrenic out-of-body experience—after all, she literally wrote the book on the subject. Upon looking into his story and meeting his twisted father, Ephraim (Bruce Davison), Elizabeth learns that an entity has possessed Asa and his father before him. It survives by passing from one host to the next, and after she’s tempted to sleep with her new patient, the act prompts a body swap, with her mind transferred into his body, and vice versa (movie pun intended). Should the entity inhabit her body three times, the switch becomes permanent.

Despite references to Lovecraft’s Cthulhu and the town of Dunwich, Paoli’s script doesn’t explore the entity’s origins. It’s more interested in placing Graham in compromising situations once the force has entered her body. A subplot involving Elizabeth’s unemployed and bizarre husband, Eddie (Johnathon Schaech), finds that the possessed Elizabeth has certain sadomasochistic appetites, which delight her husband, whereas before their sex life was getting stale before. Generally speaking, this is a horny movie, with pussy-grabby and leg-spreading scenes to provoke. However, it’s tame and somewhat edgeless compared to Gordon’s work, and it feels restrained next to the unbridled exploitation of the earlier Gordon-Paoli collaborations. This is not necessarily a complaint, just an observation that, next to the movies that inspired it, Suitable Flesh feels like the dial has been turned down.

The screen story has potential, but the execution is subpar, even sink-in-your-seat shameful at times. The production looks and sounds cheap and generic—and not charmingly so, as low-budget horror can be—with harsh lighting and Steve Moore’s score sounding like a bad imitation of Pino Donaggio. Even though Lynch and d.p. David Matthews carry out flashy camerawork and lens tricks reminiscent of De Palma (split screens, rotating movements, split diopter lenses, etc.), they don’t look like the tactics of a master as executed. Instead, they’re graceless and stilted approximations that have a crude knock-off quality. So does the green screen work in Elizabeth’s office, which hasn’t seen its equal since those rooftops in The Room (2003). And the less said about CGI smoking rings, the better. Fortunately, gorehounds will enjoy the practical effects, which get increasingly nasty as the story progresses, complete with a memorable decapitation and a body that just won’t die.

Alas, Suitable Flesh makes a better poster than a movie (that artwork is beautiful). It’s not all bad, I suppose. Graham seems to be having fun playing what amounts to multiple roles. Crampton and Davison have some pulpy and memorable scenes, though not enough screentime for either of them. But Lewis seems a tad overwhelmed by and unsuited to his role. The laughter throughout my festival screening seemed both intentional and unintentional. Still, the movie’s finale works quite well, even if asking the audience to endure what proceeds it may be asking too much. Horror fans will want to find out for themselves when RLJE Films drops the feature on VOD just in time for Halloween 2023, and then on Shudder early next year. 2/4 Stars.

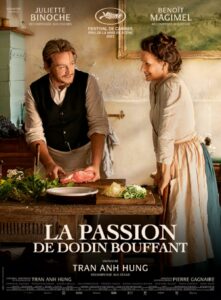

The Taste of Things

The Taste of Things

“What a perfect expression,” remarks a friend of Dodin Bouffant, the world-famous French chef and restaurant owner. At a regular gathering of haute cuisine connoisseurs, the friend has tasted Bouffant’s vol-au-vent—a dish that, to untrained eyes, looks like a bread bowl with a creamy stew inside. But the delicate pastry’s complex, rich filling includes vegetables and proteins that have taken hours to prepare. Although it’s Dodin’s recipe, his cook Eugénie has labored in the kitchen, bringing the food to life with a touch that even he cannot achieve. This dynamic between the chef and his cook, played by Benoît Magimel and Juliette Binoche in effortlessly natural performances, is the subject of The Taste of Things, writer-director Trần Anh Hùng’s latest feature that, too, might be described as a “perfect expression.”

Having emigrated to France from Vietnam when he was 12 years old, Hùng sought to explore what he saw as characteristic of French culture—the artistic passion and aesthetic logic applied to all endeavors. Using Marcel Rouff’s book from 1924, La Vie et La Passion de Dodin-Bouffant, Gourmet, as a springboard, Hùng’s portrait of Dodin and Eugénie’s relationship centers on food and remaining true to their culinary ideals. Set in 1885, the film is both a moving romance and a virtuosic triumph, both understated and engrossing in its portrait of a relationship that extends beyond the kitchen and into the nighttime hours when Dodin knocks at her door to make love. But Eugénie hesitates to marry him, despite their 20 years together. Anything not related to their refined, multilayered cuisine comes secondary. Even so, their work in the kitchen and their meals together serve as conversations, communicating their relationship not in certain terms but through the way The Taste of Things observes their interplay.

The director and his cinematographer, Jonathan Ricquebourg, employ a camera that roves around Dodin’s spacious kitchen and sways amid the cook and her assistants, often in long, unbroken takes rooted in their process. Whether they’re compiling an elaborate sauce, sipping wine that spent 50 years at the bottom of the sea, or sampling Baked Alaska, the food looks delectable. Under the supervision of French chef Pierre Gagnaire, credited as Directeur de la Gastronomie, the characters prepare actual meals. But it’s more than a cooking-show-as-cinema, even though the scenes of cooking have a certain instructional quality. While these sequences build each recipe in a transfixing progression toward the final delicacy, they also serve as an observational study of the harmony (or, evidenced later, disharmony) between the characters in Dodin’s kitchen—terrifically acted by Binoche and Magimel.

Shot in the castle commune of Segré-en-Anjou Bleu, Hùng’s film immerses the viewer into a sensuous cinematic experience, conjuring phantom smells, tastes, and sensations on our palette. Even scenes outside of the kitchen have a rhapsodic pleasure, such as simple scenes of Binoche picking vegetables in the garden or exploring a new copper antenna method of producing healthier crops. Hùng’s approach to the camera recalls the subtle, flowing movements of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s frame in Flowers of Shanghai (1999), hypnotically moving from one corner of the scene to another in delirious pleasure, while transporting the viewer to another time and place. Each image recalls the textured beauty of a Joachim Beuckelaer or Pieter Aertsen painting, and indeed, every frame of The Taste of Things looks intentional and masterfully composed. And while it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the cooking and gorgeous imagery, every meal helps us further understand Dodin and Eugénie’s unique romance.

An exquisite and subtly sophisticated feature, The Taste of Things debuted at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, where Hùng Anh Hùng won the Best Director award. There, it was called La Passion de Dodin Bouffant, before changing its name to The Pot-au-Feu, referring to a rustic French dish of boiled beef and vegetables, which, in the film, Dodin plans to elevate and serve to the Prince of Eurasia. Doubtlessly too obscure for non-French audiences who didn’t grow up eating this common recipe, the title changed to The Taste of Things under US distributor IFC Films and will represent France’s bid for the Best International Feature Film at the 96th Academy Awards. Foodie and Francophiles alike will melt in its richness. This is surely one of the best films of 2023. And doubtless, whatever meal you eat afterward will be inadequate. 4/4 Stars.

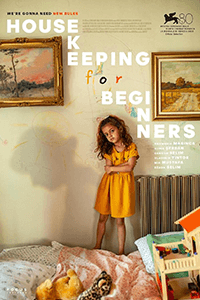

Housekeeping for Beginners

Housekeeping for Beginners

In his third feature, Housekeeping for Beginners (Domaḱinstvo za početnici), filmmaker Goran Stolevski (You Won’t Be Alone, 2022) paints a rocky portrait of an unconventional family in North Macedonia. Set in a country largely opposed to LGBTQ+ rights, the film centers on a house situated in the capital city of Skopje. There, a lesbian couple and several of their female friends live with two gay men and two children, making up a chaotic refuge of strong personalities that often clash over their differences. But they also have nowhere else to go where their lifestyles—and in some cases, ethnicities—would be accepted without prejudice. Made with immediacy and sincerity, the film requires some time to find Stolevski’s rhythm, but patience on the viewer’s part will be rewarded with a surprisingly affecting drama.

Anamaria Marinca (4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, 2007) stars as Dita, a social worker in a relationship with Suada (Alina Serban), who has two children from a previous marriage—the rebellious Vanessa (Mia Mustafa) and the precocious, no-bullshit six-year-old Mia (DŽada Selim). Before Suada loses her battle with cancer, she forces Dita to make a promise: Dita must agree to watch over Suada’s children and provide them with the best possible future. This means Dita must marry their queer housemate Toni (Vladimir Tintor), whose last name, Acevski, sounds white. Sauda has a Roma background, and throughout the region, the Roma people still face racial intolerance, including fewer schooling and career opportunities. In short, Dita must pass as straight in order for Vanessa and Mia to pass as white and have every chance they deserve. They’re aided by Toni’s new lover Ali (Samson Selim), who arranges to change the children’s birth certificates to reflect Toni as their biological father.

While its setup sounds reminiscent of several romantic comedies where a character must pretend to be straight or gay to get close to someone or earn a family’s approval, Housekeeping for Beginners never feels formulaic. Nor does it feel preachy, even though Macedonian intolerance propels the characters into this situation. Their life on the margins of so-called conventional society is illustrated when Dita and Toni must attend an awkward dinner with friends or, at several points in the story, when Dita and company must visit Shutka, the Roma-led suburb—often for Vanessa, who tries to escape her new “parents” more than once. Even though they remain outsiders, they own their status. Everyone in the house casually tosses around epithets such as “fag” and “gypsy” within their many harsh insults to each other (“Go suck your mother’s dick” was a favorite of mine).

Serving as writer, director, and editor, Stolevski evokes the rambunctious energy and interest in outcasts found in the work of Swedish helmer Lukas Moodysson. To be sure, the film contains the queer sentimentality of Fucking Åmål (1998), the makeshift family of Together (2000), and even a disturbing hint of sex trafficking like Lilya 4-ever (2002). With its characters socially and physically cramped, Stolevski and d.p. Naum Doksevski employ a boxy aspect ratio. Along with coarse edits and frantic, handheld camerawork—also recalling the rough-around-the-edges energy of Moodysson’s films—the filmmaker embraces a similar brand of sentimentality in its raw-nerve emotions.

Somehow, it all comes together into a warm-hearted family drama that pulls on your heartstrings. No wonder it earned the Queer Lion Award at the Venice Film Festival this year, while next year, it will represent Macedonia’s entry for the Best International Feature Film at the Oscars. Housekeeping for Beginners is a warm and alternately volatile experience, underscoring the necessity to build a village or support system, especially where the threat of intolerance is present. Full of natural performances and a narrative that might be accused of a Hollywood ending, Stolevski’s film is a pleasant interplay between cultural portrait and crowd-pleasing dramedy. 3/4 Stars.

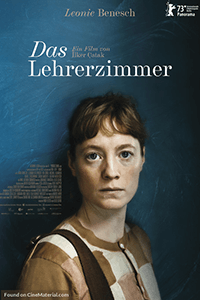

The Teachers’ Lounge

The Teachers’ Lounge

A thoroughly readable and thought-provoking film by German director İlker Çatak, The Teachers’ Lounge is a parable bound to prompt debates about trust, profiling, obedience, independence, authority, and subjectivity. More specifically, the film explores how people of varied backgrounds operate within social systems, using a school and the fraught dynamic between teachers and students as a metaphor for larger social problems. Building tension with urgent, claustrophobic camerawork and Marvin Miller’s score of agitated strings, Çatak makes the already harried surroundings of a junior high into a pressure-cooker environment. It’s not some haven where students learn about the real world; it’s a world unto itself, reflecting and reinforcing the problems children will face for the rest of their lives.

The story opens with an investigation into missing money after a series of petty thefts on school property. A new seventh-grade math and gym teacher from Poland, Carla Nowak (Leonie Benesch), unwittingly participates when two fellow instructors interrogate two class representatives about this “unpleasant” issue, asking them to name anyone who might be a suspect and keep the investigation quiet. When they cast suspicions about their Turkish classmate, Ali (Can Rodenbostel), the resulting exchange between Ali’s parents, the principal (Anne-Kathrin Gummich), and Nowak finds the staff unequipped to handle their investigation—due to the prejudiced accusations made against Ali.

But Nowak isn’t beyond reproach. She sets up a trap for the culprit, leaving her wallet inside her jacket in the teachers’ lounge and a laptop recording. The video she records has “credible clues” that an office admin, Mrs. Kuhn (Eva Löbau), stole money from Nowak’s wallet. But the evidence is not beyond a reasonable doubt. Even so, the school forces Mrs. Kuhn to take a vacation while they conduct an investigation. The problem is that Mrs. Kuhn’s son, Oskar (Leonard Stettnisch), is the brightest student in Nowak’s class. After hearing that his teacher made an accusation against his mother, he rallies the students in his favor and gradually tears apart Nowak’s credibility. How does the school deal with this dissenter, who refuses to entertain any accusation? There’s no right answer. Meanwhile, Nowak tries to remain in the students’ favor, but doing so aggravates her coworkers who expect solidarity.

From start to finish, cinematographer Judith Kaufman’s sharp, crystalline camerawork follows Nowak in confronting situations where Benesch shines in her ability to convey her character’s fraying patience. The director is perhaps too quick to resort to a hallucinatory sequence to convey the state of Nowak’s mind, whereas a scene in which she asks her class to scream as loud as they can better encapsulates her mental state. Çatak and his co-writer Johannes Duncker create parallel scenes where Nowak faces angry parents who want answers at a group conference, and later, in a classroom of students who demand the same transparency. The children prove smarter than she treats them, as evidenced in a scene where she’s interviewed by a shrewd newsroom of junior reporters for the school paper. They assemble quickly against her, and when they refuse obedience, there’s not much anyone can do to stop them.

The Teachers’ Lounge looks at the tenuous illusion of society, and how it attempts a “common solution” for everyone, yet more often than not, someone is excluded or ostracized by society’s penchant for generalities and desperate need to maintain control. Banning unpopular opinions, preventing discourse, and avoiding or inadequately addressing conflict often take the place of confronting the truth head-on. But the young writers of the student paper know this better than the self-interested faculty of the school by following their motto, “Truth overcomes all bonds.” Everything else is “PR,” the students say. Çatak takes an edgy look at a specific situation that reaches into countless facets of the human experience, from how adults treat children to politics. While laying bare the hypocrisy and faulty logic of social systems, Çatak celebrates the outsiders who ask questions and refuse to blindly conform. There’s a sly brilliance at work here that may not get fully resolved in dramatic terms, but it gives the viewer much to consider. 3.5/4 Stars.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review