Velvet Buzzsaw

By Brian Eggert |

Despite its impressive roster of talent, including writer-director Dan Gilroy and stars Jake Gyllenhaal and Rene Russo—the trio who worked on the superb Nightcrawler (2014)—the Netflix release Velvet Buzzsaw can be seen as an unnecessary portrait of the commodification and elitism in the contemporary art market. It begins as a darkly comic representation of the artists, snobs, intellectuals, hipsters, pseudo-intellectuals, wannabes, and pretentions abound in the Los Angeles art scene, and then it descends into a kind of slasher movie. But the killer isn’t a masked psycho; it’s a series of deadly paintings created by a demonic artist. With A-list talent both in front and behind the camera, it’s easy to admire the production for its audacity. And as Velvet Buzzsaw carries on, and its downright strangeness takes over, one even respects the unconventional leaps it’s willing to take—some bizarro performances among them. The switch in tone at the midpoint, shifting from satire to horror, is bound to either spoil the viewer’s investment or endear them to the material. Either way, Gilroy’s themes prove agitated and ultimately ignorant about the relationship between art and commerce.

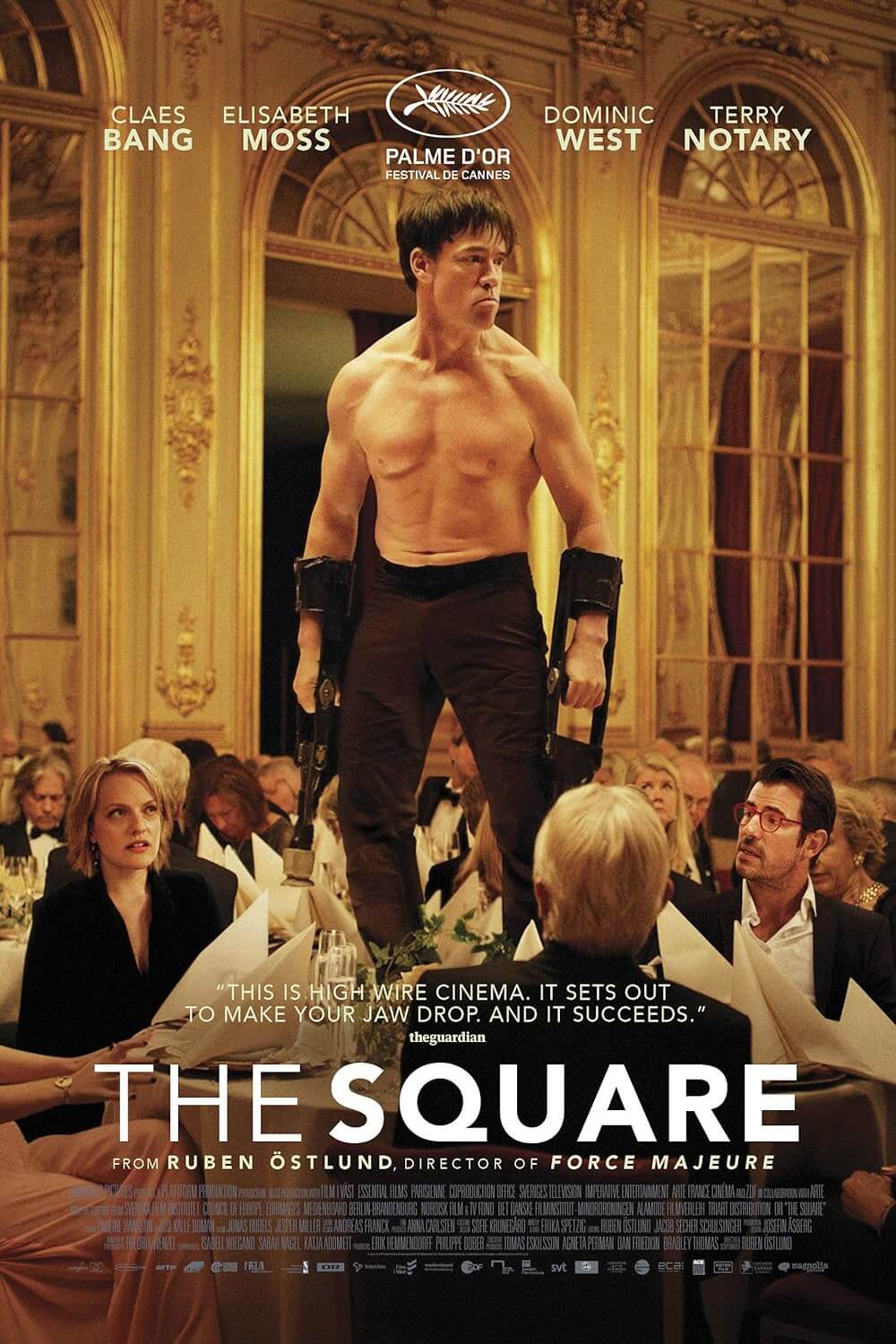

At the outset, Velvet Buzzsaw might resemble Ruben Östlund’s 2017 Palme d’Or winner The Square, or even the recent HBO documentary The Price of Everything (2018), as Gilroy cuts into the absurd pretense and marketization of modern art. An admirably go-for-broke Gyllenhaal stars as Morf Vandewalt, the most influential critic of contemporary art in L.A. He attends local shows, offering his either hyperbolic praise or damning dismissal of whatever pieces affect him most. Take the large reflective sphere that is embedded with holes inside of which the spectator is meant to reach to discover something unique. Morf reaches into the sphere—an apparent spoof of Jeff Koons’ vacuous Gazing Balls that sell for millions today—and finds his “primal consciousness.” Meanwhile, gallery owner Rhodora Haze (Russo) seeks to find the latest and greatest acquisitions for exhibition, relying on lackeys like the desperate Josephina (Zawe Ashton) or naïve part-timer Coco (Natalia Dyer) to do her bidding. They hover around one-named artists, such as Basquiat stand-in Damrish (Daveed Diggs) or abstract expressionist Piers (John Malkovich), hoping to secure their latest work for Rhodora’s gallery—attempting to convince them with lines like “we have customized analytics to maximize deal flow.”

It’s all about marketing more than art, and Gilroy takes out his contempt for this scene—where people have “taste relationships” instead of real interpersonal bonds—by introducing a supernatural wrinkle. When Josephina finds her mysterious, elderly neighbor named Vetril Dease collapsed in a hallway, she snoops in the dead man’s cluttered apartment to find dozens of paintings in a style reminiscent of Francisco de Goya and Francis Bacon, depicting excessively violent and soul-wrenching scenes. She shows them to Morf, her new lover, and he’s entranced. So is everyone else. Dease’s paintings have a way of haunting the spectator. And as everyone scrambles to exploit this new undiscovered artist’s work—Rhodora wants them for her gallery, Morf will write a book about them, and curator Gretchen (Toni Collette) wants to start an independent career by dealing his paintings—Dease’s art responds. It turns out the paintings contain some manner of spell that curses the observer, as well as other artwork viewed by the observer. The spell on Dease’s art brings itself and other art to life, killing spectators in a series of freak accidents (or whatever).

One can’t be certain of the fuzzy rules here, but once people succumb to Dease’s art, Velvet Buzzsaw becomes a dull exercise in elaborate death. For instance, there’s a scene where Gretchen puts her arm into the aforementioned sphere, and the piece reacts by chopping it off. The next morning, visitors to the gallery assume her dead body and pools of blood are part of a new installation. Indeed, Gilroy’s screenplay, while occasionally funny on its dark path, is never thoughtfully considered. His characters speak in banal dialogue, saying things like “Listen to my intelligent mind” or “Did you know the gallery opening is actually trending on Twitter?” Of course, their hollow dialogue may be a symptom of Gilroy’s contempt for his characters, but that makes it no less intolerable. His characters also inhabit empty relationships to which the viewer cannot relate. Although Gilroy intends to portray these people as an empty, soulless bunch, he nonetheless inserts scenes of drama, as if we’re supposed to care. But none of the emotional scenes are justified by character development or empathy. So when Morf and Josephina engage in several discussions about their failing romance, it’s difficult to feel invested, since Gilroy wants to see them dead anyway.

It’s all a bit too over-the-top and unsubtle, if not painfully one-dimensional. Gilroy makes poor use of cinematographer Robert Elswit and the wonderful cast for a film that deems gristly death as a kind of poetic justice for those who would commodify art. But art for creation’s sake is a relatively new idea in the grand history of art, emerging as of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Before the appearance of modern and conceptual art, paintings and sculptures were created by artists who were backed by schools, institutions, and patrons in a relationship that considered artwork another commodity in a market of worldly goods. Works by the great masters, from Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa to Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, were commissions, and yet they’re timeless. (Who will remember Gazing Balls in 500 years?) Gilroy suggests that those who would profit from or exploit art deserve to die from it. His primary example is Rhodora, a former punk rocker and renegade who has since sold out, making her “No Death. No Art.” tattoo an artifact of a purer time. Rhodora’s other tattoo, a blade with the name of her former punk band “Velvet Buzzsaw,” comes alive in the end and saws through her neck. But Gilroy forgets that art, even bad art like Velvet Buzzsaw, usually requires someone to pay for it. Granted, the relationship between art and the art market is sometimes sickening, but artists cannot survive on aesthetic purity alone.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review