Reader's Choice

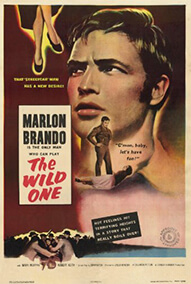

The Wild One

By Brian Eggert |

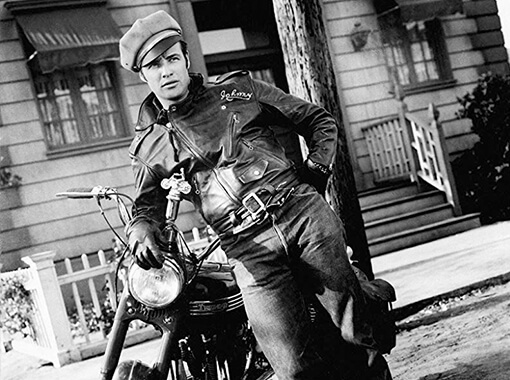

“Hey, Johnny, what are you rebelling against?” asks a young a rube from Squaresville, USA. “Whaddya got?” replies Johnny, Marlon Brando’s leather-clad, emotionally detached leader of the Black Rebels Motorcycle Club. It’s an iconic moment in The Wild One, a film remembered more for Brando’s screen persona and the sheer influence of his appearance than the content of the film itself. The first of several films in the 1950s about outlaw bikers and out-of-control teen gangs, its legacy resides in its imagery. Dramatically, not much about the film evokes genuine emotion today; Johnny and his wandering quest for rebellion fail to resonate in the way they might have in 1953. But in the years following its release, teen culture adopted Johnny’s streak of aimless dissent, bikers used Brando’s getup as a template for their standard costume, and much later, the queer community adopted Johnny’s look, as did S&M subculture. It’s a film of unintentionally conflicting ideas and ironic uncertainties, resulting in a work that lends itself to a camp sensibility and an inadvertent challenge to traditional masculine roles. However fascinating these unintended consequences may be, the surface of The Wild One has lost its edge.

Screenwriters John Paxton and Ben Maddow based The Wild One on a 1947 incident that occurred in the small town of Hollister, California. A motorcycle gang calling themselves The Boozefighters rode into town and proceeded to drink beer and race their bikes in the street, and the locals felt they had been held hostage for the ensuing two days of rowdy behavior (which was limited to some public drunkenness and overcrowding). These so-called riots were fictionalized in Frank Roone’s story “The Cyclists’ Raid,” published in Harper’s Magazine in January 1951. Roone demonized biker gangs for the American public, and his story, told from the perspective of a hotel owner with a teenage daughter, suggested that bikers would cause civil unrest and even pose a threat to the girl. Producer Stanley Kramer chose the subject for his next collaboration with the Hungarian-born director Laslo Benedek. The two had just completed work on their film of Arthur Miller’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Death of a Salesman, a 1951 release starring Fredric March. Perhaps it was their stage-to-screen pedigree that convinced Brando, fresh off memorable performances in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) and Julius Caesar (1953), to star in a sensational biker movie.

Brando gives an iconic, mumbling performance as Johnny Strabler. Fixed in the actor’s distinct mannerisms, Johnny appears distracted, always rubbing his eyes or looking at his hands, ever uncertain of what he’s going to say and why. When his gang rides into a small California town, the group of young men uses violent language (such as “Blood makes everything slippery!”) and causes a couple of minor car accidents. But they’re just posturing, “trying to show how tough they are,” as one local observes. The BRMCs are later joined by a motorcycle gang called the Beetles, led by Chino (Lee Marvin), who’s dressed like a Halloween pirate. Together, the gangs drink copious amounts of pilsner; talk jive, much to the confusion of the local squares; dump garbage into the street; chase after young local girls; hop on pogo sticks; ride their motorcycles indoors; and generally upset the resident population. Through much of these shenanigans, Johnny remains on the periphery, more concerned with Kathie (Mary Murphy), the daughter of the Police Chief (Robert Keith). Eventually, the townspeople organize into a militia to take back their town, focusing their attention on Johnny. But in their attempt to corner him, their attack leads to a deadly accident.

Brando gives an iconic, mumbling performance as Johnny Strabler. Fixed in the actor’s distinct mannerisms, Johnny appears distracted, always rubbing his eyes or looking at his hands, ever uncertain of what he’s going to say and why. When his gang rides into a small California town, the group of young men uses violent language (such as “Blood makes everything slippery!”) and causes a couple of minor car accidents. But they’re just posturing, “trying to show how tough they are,” as one local observes. The BRMCs are later joined by a motorcycle gang called the Beetles, led by Chino (Lee Marvin), who’s dressed like a Halloween pirate. Together, the gangs drink copious amounts of pilsner; talk jive, much to the confusion of the local squares; dump garbage into the street; chase after young local girls; hop on pogo sticks; ride their motorcycles indoors; and generally upset the resident population. Through much of these shenanigans, Johnny remains on the periphery, more concerned with Kathie (Mary Murphy), the daughter of the Police Chief (Robert Keith). Eventually, the townspeople organize into a militia to take back their town, focusing their attention on Johnny. But in their attempt to corner him, their attack leads to a deadly accident.

As always, Brando is fascinating to watch, and his signature look and attitude in the film, epitomized by his biker duds, reverberated through the remaining years of the 1950s and beyond. His sideburns inspired Elvis, who recorded his first song in Memphis just a year after The Wild One’s debut. Some combination of Johnny’s jacket and Chino’s striped pirate shirt informed the costumes in Jailhouse Rock (1957). Brando’s own Triumph Thunderbird 6T motorcycle led to higher sales of that model. Hollywood responded by making several teen rebel movies. Johnny’s inability to articulate his angst led to James Dean’s titular character in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), a film better suited to negotiate the complex emotional dynamics of its confused, disaffected main character and teenage youth culture overall. Conservative circles worried The Wild One would encourage juvenile gangs, or that younger viewers would repeat the behavior shown in the film. Milton Luban wrote of the film in his review for The Hollywood Reporter, “Its main appeal would seem to be to those lawless juveniles who may well be inspired to go out and emulate the characters portrayed.” Fearing a wave of teenage rebellion, the British Board of Film Censors banned the film for 14 years. Around the same time, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover alerted the American public to the “flood tide” of youth violence in the 1950s, while some feared that same-sex groups of juvenile delinquents led to homosexuality.

Indeed, part of the controversy surrounding The Wild One stemmed not only from its representation of violent youth gangs but also the associated queer subtexts. In his book The Myth of the Queer Criminal, author Jeffery P. Dennis details the findings of criminologists from the era, who determined that boys involved in teen gangs engaged in latent homosexual behavior—they assert their toughness to hide an inner gay impulse. While the stigma around homosexuality in the 1950s undoubtedly shaped the results of such problematic studies, it’s impossible to deny the air of homoeroticism in both The Wild One and other films about youth gangs. Certainly, the onscreen relationship between James Dean and Sal Mineo in Rebel Without a Cause reads as homoerotically charged, especially given the rumored bisexuality of its performers and its director, Nicholas Ray. In a scene in The Wild One, BRMC members don makeshift wigs and dance with one another in their leather costumes, while Brando’s performance, and the camera’s ogling of Johnny’s tight blue jeans, has a sexual uncertainty that leads to queer interpretations. Although Johnny’s Perfecto leather jacket became the signature garb of many masculine-centric motorcycle clubs, queer culture adopted the look as well, combined with a biker hat cocked to one side. It’s a look that has been incorporated into queer contexts from Andy Warhol’s photo portrait of art historian John Richardson to a disguise worn by Al Pacino in Cruising (1980), director William Friedkin’s thriller about a serial killer targeting gay men. It also shaped Shia LaBeouf’s appearance as Mutt Williams in Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008).

In the end, the viewer of The Wild One thinks back to the warning of the opening titles: “It is a public challenge not to let it happen again.” But what was happening in the film? The moral position of the filmmakers, and apparently the British Board of Film Censors, is that the bikers should have never ridden their motorcycles into small-town America, and therefore such people run contrary to fundamental American values. It also implies that Americans should fear a similar youth gang doing the same in their town. However, the townspeople panicked and retaliated by turning into a lynch mob, and it wasn’t until then that someone died. The lesson of this morality play, if that’s what The Wild One means to be, remains fuzzy today, even if in 1953 the message against juvenile delinquents was apparent to some. This moral element is contrasted by Johnny’s sympathetic and inward presence, his almost feminine-coded vulnerability, even though most of his compatriots prove to be animalistic and one-note. Listen to Johnny’s wishy-washy narration, the only narration in the film, after the opening titles: “How the whole mess happened, I don’t know. But I know it couldn’t happen again in a million years.” Johnny’s regret, combined with the fact that the townsfolk caused the death of one of their own, remain in conflict with the cautionary tale’s message against juvenile gangs, leaving the film confused about what it’s trying to say.

In the end, the viewer of The Wild One thinks back to the warning of the opening titles: “It is a public challenge not to let it happen again.” But what was happening in the film? The moral position of the filmmakers, and apparently the British Board of Film Censors, is that the bikers should have never ridden their motorcycles into small-town America, and therefore such people run contrary to fundamental American values. It also implies that Americans should fear a similar youth gang doing the same in their town. However, the townspeople panicked and retaliated by turning into a lynch mob, and it wasn’t until then that someone died. The lesson of this morality play, if that’s what The Wild One means to be, remains fuzzy today, even if in 1953 the message against juvenile delinquents was apparent to some. This moral element is contrasted by Johnny’s sympathetic and inward presence, his almost feminine-coded vulnerability, even though most of his compatriots prove to be animalistic and one-note. Listen to Johnny’s wishy-washy narration, the only narration in the film, after the opening titles: “How the whole mess happened, I don’t know. But I know it couldn’t happen again in a million years.” Johnny’s regret, combined with the fact that the townsfolk caused the death of one of their own, remain in conflict with the cautionary tale’s message against juvenile gangs, leaving the film confused about what it’s trying to say.

Ultimately, the film’s intended message against youth and biker gangs backfired. Instead of creating awareness and inciting fear, American culture clung to Brando’s image and Johnny’s line, “Whaddya got?” Rebelliousness turned into the hallmark of rock-and-roll culture and a subset of teen cinema; it was innate to the new market of teenage consumers of the 1950s. Over time, the threat of delinquent gangs subsided, and the film’s influence reached from biker gangs to leather bars. Today, The Wild One lends itself to naïve camp readings in queer analysis, where it can be interpreted that Johnny resists the traditions of straight society and perhaps remains unable or unwilling to confess his gayness. After all, he doesn’t remain with Kathie. He rides off on his motorcycle, all alone and, as John Waters might say, “ludicrously tragic”—this is regardless of Kathie making her feelings clear when she strokes his motorcycle’s long fender, confessing how she felt about her first ride on a bike: “It was fast. It felt good.” Even if the film’s intended drama and social commentary prove inept, if not somewhat laughable, The Wild One’s status as a cultural marker remains undeniable.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon by Ron. Thanks for your continued support!)

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review